「カプセル化細胞」の版間の差分

m →歴史 |

|||

| 5行目: | 5行目: | ||

== 歴史 == |

== 歴史 == |

||

<font style="background-color: rgb(255, 255, 255);">1933年にVincenzo Bisceglieは、ポリマーの膜に細胞をカプセル化する最初の試みを行った。彼は、ブタの腹腔に移植されたポリマー膜の中の腫瘍細胞は、免疫系によって拒絶されることなく、長期間生存可能であることを実証した</font>。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bisceglie V|author=Bisceglie V|year=1993|title=Uber die antineoplastische Immunität; heterologe Einpflanzung von Tumoren in Hühner-embryonen|journal=Zeitschrift für Krebsforschung|volume=40|pages=122–140| |

<font style="background-color: rgb(255, 255, 255);">1933年にVincenzo Bisceglieは、ポリマーの膜に細胞をカプセル化する最初の試みを行った。彼は、ブタの腹腔に移植されたポリマー膜の中の腫瘍細胞は、免疫系によって拒絶されることなく、長期間生存可能であることを実証した</font>。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bisceglie V|author=Bisceglie V|year=1993|title=Uber die antineoplastische Immunität; heterologe Einpflanzung von Tumoren in Hühner-embryonen|journal=Zeitschrift für Krebsforschung|volume=40|pages=122–140|doi=10.1007/bf01636399}}</ref> |

||

30年後の1964年に、超薄型高分子膜のマイクロカプセル内に細胞を封入することで、細胞に免疫に対しての防御を与えるというアイデアが、Thomas Changによって提案された。<ref name="pmid14190240">{{Cite journal|last=Chang TM|author=Chang TM|date=October 1964|title=Semipermeable microcapsules|journal=Science|volume=146|issue=3643|pages=524–5| |

30年後の1964年に、超薄型高分子膜のマイクロカプセル内に細胞を封入することで、細胞に免疫に対しての防御を与えるというアイデアが、Thomas Changによって提案された。<ref name="pmid14190240">{{Cite journal|last=Chang TM|author=Chang TM|date=October 1964|title=Semipermeable microcapsules|journal=Science|volume=146|issue=3643|pages=524–5|doi=10.1126/science.146.3643.524|pmid=14190240}}</ref> カプセル化された細胞は、免疫拒絶から保護されるだけでなく、体積に対する表面積が大きくなり、それが酸素と栄養素の良好な移動を可能にすることも、示唆している。<ref name="pmid14190240">{{Cite journal|last=Chang TM|author=Chang TM|date=October 1964|title=Semipermeable microcapsules|journal=Science|volume=146|issue=3643|pages=524–5|doi=10.1126/science.146.3643.524|pmid=14190240}}</ref>20年後、このアプローチは、小動物をモデルにし、実践された。すい臓のランゲルハンス島(膵島)の細胞を、アルギン酸塩 - ポリリジン - アルギン酸(APA)マイクロカプセルで、固定化し、異種間移植された。<ref name="pmid6776628">{{Cite journal|date=November 1980|title=Microencapsulated islets as bioartificial endocrine pancreas|journal=Science|volume=210|issue=4472|pages=908–10|doi=10.1126/science.6776628|pmid=6776628}}</ref> この研究では、マイクロカプセル化したすい臓のランゲルハンス島を、糖尿病のラットに移植すると、細胞が生存し、数週間にわたって血糖を制御し続けたことを実証した。カプセル化された細胞を利用したヒトへの試験は1998年に実施された。<ref name="Löhr 393–8">{{cite journal|last=Löhr|first=M|date=April 1999|title=Cell therapy using microencapsulated 293 cells transfected with a gene construct expressing CYP2B1, an ifosfamide converting enzyme, instilled intra-arterially in patients with advanced-stage pancreatic carcinoma: a phase I/II study.|journal=Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany)|volume=77|issue=4|pages=393–8|author2=Bago, ZT|author3=Bergmeister, H|author4=Ceijna, M|author5=Freund, M|author6=Gelbmann, W|author7=Günzburg, WH|author8=Jesnowski, R|author9=Hain, J|author10=Hauenstein, K|author11=Henninger, W|author12=Hoffmeyer, A|author13=Karle, P|author14=Kröger, JC|author15=Kundt, G|author16=Liebe, S|author17=Losert, U|author18=Müller, P|author19=Probst, A|author20=Püschel, K|author21=Renner, M|author22=Renz, R|author23=Saller, R|author24=Salmons, B|author25=Walter, I|pmid=10353444|doi=10.1007/s001090050366}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Löhr|first=M|date=May 19, 2001|title=Microencapsulated cell-mediated treatment of inoperable pancreatic carcinoma.|journal=Lancet|volume=357|issue=9268|pages=1591–2|doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04749-8|pmid=11377651}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lohr|first=M|year=2003|title=Safety, feasibility and clinical benefit of localized chemotherapy using microencapsulated cells for inoperable pancreatic carcinoma in a phase I/II trial|journal=Cancer Therapy|volume=1|pages=121–31}}</ref> 進行性の切除不能なすい臓がんの臨床試験として、抗腫瘍効果を局所的に発揮するために、[[シトクロムP450]]酵素を発現するカプセル化細胞が腫瘍部位に移植され、シトクロムP450に分解されて抗腫瘍効果を発揮する[[プロドラッグ]]が患者に投与された。対照と比較して約2倍の生存期間が示された。 |

||

== 組織工学と再生医療のためのツールとしての、細胞のマイクロカプセル化 == |

== 組織工学と再生医療のためのツールとしての、細胞のマイクロカプセル化 == |

||

細胞のカプセル化技術のメリットの1つめは、移植部位で、より長い期間にわたり、治療用物質を放出できることである。例えば、インスリンを毎食後注射しないといけない糖尿病に対して、カプセル化技術によるすい臓細胞を移植することで、インスリンを注射しi jなくてすむ。細胞のマイクロカプセル化技術のもう1つの利点は、適合するドナーがいない場合でも、ヒト以外の動物の細胞や、遺伝子改変細胞を、ポリマーでカプセル化することで使用可能になることである。<ref name="pmid18789985">{{Cite journal|date=December 2008|title=Cell microencapsulation technology: towards clinical application|journal=J Control Release|volume=132|issue=2|pages=76–83| |

細胞のカプセル化技術のメリットの1つめは、移植部位で、より長い期間にわたり、治療用物質を放出できることである。例えば、インスリンを毎食後注射しないといけない糖尿病に対して、カプセル化技術によるすい臓細胞を移植することで、インスリンを注射しi jなくてすむ。細胞のマイクロカプセル化技術のもう1つの利点は、適合するドナーがいない場合でも、ヒト以外の動物の細胞や、遺伝子改変細胞を、ポリマーでカプセル化することで使用可能になることである。<ref name="pmid18789985">{{Cite journal|date=December 2008|title=Cell microencapsulation technology: towards clinical application|journal=J Control Release|volume=132|issue=2|pages=76–83|doi=10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.08.010|pmid=18789985}}</ref> マイクロカプセルは、いろいろな組織や器官に移植することができ、局所的な治療も、経口投与もできる貴重な技術である。治療部位への薬物が届くまでの距離はふつうは長く、それに比べれば、カプセル化細胞の移植は直接薬物を届けるため、よりコストがかからない。さらに、患者の移植適合抗原を気にせず、同じカプセル化細胞を移植できれば、コストを低減できるだろう。<ref name="pmid18789985">{{Cite journal|date=December 2008|title=Cell microencapsulation technology: towards clinical application|journal=J Control Release|volume=132|issue=2|pages=76–83|doi=10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.08.010|pmid=18789985}}</ref> |

||

== 細胞のマイクロカプセル化技術の要素 == |

== 細胞のマイクロカプセル化技術の要素 == |

||

| 19行目: | 19行目: | ||

==== アルギン酸 ==== |

==== アルギン酸 ==== |

||

いくつかの研究グループにより、細胞のマイクロカプセル化に最適な生体材料を開発することを目的として、いくつかの天然および合成の高分子が幅広く研究されてきた。<ref name="pmid15763258">{{Cite journal|date=August 2005|title=Development of mammalian cell-enclosing subsieve-size agarose capsules (<100 microm) for cell therapy|journal=Biomaterials|volume=26|issue=23|pages=4786–92| |

いくつかの研究グループにより、細胞のマイクロカプセル化に最適な生体材料を開発することを目的として、いくつかの天然および合成の高分子が幅広く研究されてきた。<ref name="pmid15763258">{{Cite journal|date=August 2005|title=Development of mammalian cell-enclosing subsieve-size agarose capsules (<100 microm) for cell therapy|journal=Biomaterials|volume=26|issue=23|pages=4786–92|doi=10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.043|pmid=15763258}}</ref><ref name="pmid15532084">{{Cite journal|date=December 2004|title=Towards a fully synthetic substitute of alginate: optimization of a thermal gelation/chemical cross-linking scheme ("tandem" gelation) for the production of beads and liquid-core capsules|journal=Biotechnol. Bioeng.|volume=88|issue=6|pages=740–9|doi=10.1002/bit.20264|pmid=15532084}}</ref> [[アルギン酸]]は、豊富に入手可能、優れた生体適合性、および生物分解性により、細胞のマイクロカプセル化に最も適した生体材料と見なされ、広範な研究がなされている。アルギン酸は、海藻および細菌<ref name="pmid6801192">{{Cite journal|date=July 1981|title=Isolation of alginate-producing mutants of Pseudomonas fluorescens, Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas mendocina|journal=J. Gen. Microbiol.|volume=125|issue=1|pages=217–20|doi=10.1099/00221287-125-1-217|pmid=6801192}}</ref> から抽出することができる天然ポリマーである。分離する元の素材に応じてさまざまな組成をもつ。<ref name="pmid6801192">{{Cite journal|date=July 1981|title=Isolation of alginate-producing mutants of Pseudomonas fluorescens, Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas mendocina|journal=J. Gen. Microbiol.|volume=125|issue=1|pages=217–20|doi=10.1099/00221287-125-1-217|pmid=6801192}}</ref> |

||

アルギン酸も、いくつかの欠点があると指摘されている。高M含量のアルギン酸は炎症反応を引き起こし<ref name="pmid1931864">{{Cite journal|date=August 1991|title=Induction of cytokine production from human monocytes stimulated with alginate|journal=J. Immunother.|volume=10|issue=4|pages=286–91| |

アルギン酸も、いくつかの欠点があると指摘されている。高M含量のアルギン酸は炎症反応を引き起こし<ref name="pmid1931864">{{Cite journal|date=August 1991|title=Induction of cytokine production from human monocytes stimulated with alginate|journal=J. Immunother.|volume=10|issue=4|pages=286–91|doi=10.1097/00002371-199108000-00007|pmid=1931864}}</ref><ref name="pmid7678226">{{Cite journal|date=January 1993|title=The involvement of CD14 in stimulation of cytokine production by uronic acid polymers|journal=Eur. J. Immunol.|volume=23|issue=1|pages=255–61|doi=10.1002/eji.1830230140|pmid=7678226}}</ref> 異常な細胞増殖を引き起こすと指摘されている。<ref name="pmid1990681">{{Cite journal|date=February 1991|title=An immunologic basis for the fibrotic reaction to implanted microcapsules|journal=Transplant. Proc.|volume=23|issue=1 Pt 1|pages=758–9|pmid=1990681}}</ref> <ref name="pmid1765902">{{Cite journal|year=1991|title=The effect of capsule composition on the biocompatibility of alginate-poly-l-lysine capsules|journal=J Microencapsul|volume=8|issue=2|pages=221–33|doi=10.3109/02652049109071490|pmid=1765902}}</ref><ref name="pmid16574222">{{Cite journal|date=July 2006|title=Biocompatibility of alginate-poly-l-lysine microcapsules for cell therapy|journal=Biomaterials|volume=27|issue=20|pages=3691–700|doi=10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.048|pmid=16574222}}</ref> <ref name="pmid9031730">{{Cite journal|date=February 1997|title=Effect of the alginate composition on the biocompatibility of alginate-polylysine microcapsules|journal=Biomaterials|volume=18|issue=3|pages=273–8|doi=10.1016/S0142-9612(96)00135-4|pmid=9031730}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=De Vos|editor-last=Kühtreiber|editor-first=Willem M.|first=Paul|title=Cell Encapsulation Technology and Therapeutics|date=September 1999|publisher=Birkhäuser Boston|ISBN=978-0-8176-4010-1|chapter=Biocompatibility issues|last2=R. van Schifgaarde|author2=R. van Schifgaarde|editor1-last=Kühtreiber|editor2-last=Lanza|editor3-last=Chick|editor1-first=Willem M.|editor2-first=Robert P.|editor3-first=William L.}}</ref>超高純度のアルギン酸でさえ、[[エンドトキシン]]や、細胞のマイクロカプセルの生体適合性を損なう可能性のあるポリフェノールを含有している可能性がある。<ref name="pmid16574222">{{Cite journal|date=July 2006|title=Biocompatibility of alginate-poly-l-lysine microcapsules for cell therapy|journal=Biomaterials|volume=27|issue=20|pages=3691–700|doi=10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.048|pmid=16574222}}</ref><ref name="pmid16265647">{{Cite journal|date=February 2006|title=Evaluation of alginate purification methods: effect on polyphenol, endotoxin, and protein contamination|journal=J Biomed Mater Res A|volume=76|issue=2|pages=243–51|doi=10.1002/jbm.a.30541|pmid=16265647}}</ref><ref name="pmid16154192">{{Cite journal|date=March 2006|title=Impact of residual contamination on the biofunctional properties of purified alginates used for cell encapsulation|journal=Biomaterials|volume=27|issue=8|pages=1296–305|doi=10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.08.027|pmid=16154192}}</ref> 臨床用途に使用するためには、アルギン酸から不要な物質を除去できる、効果的な精製プロセスの設計が不可欠である。 |

||

===== アルギン酸の修飾と機能化 ===== |

===== アルギン酸の修飾と機能化 ===== |

||

アルギン酸を修飾した、マイクロカプセルの開発もされている。<ref name="pmid12579568">{{Cite journal|date=March 2003|title=Improvement of the biocompatibility of alginate/poly-l-lysine/alginate microcapsules by the use of epimerized alginate as a coating|journal=J Biomed Mater Res A|volume=64|issue=3|pages=533–9| |

アルギン酸を修飾した、マイクロカプセルの開発もされている。<ref name="pmid12579568">{{Cite journal|date=March 2003|title=Improvement of the biocompatibility of alginate/poly-l-lysine/alginate microcapsules by the use of epimerized alginate as a coating|journal=J Biomed Mater Res A|volume=64|issue=3|pages=533–9|doi=10.1002/jbm.a.10276|pmid=12579568}}</ref><ref name="pmid12579569">{{Cite journal|date=March 2003|title=Microcapsules made by enzymatically tailored alginate|journal=J Biomed Mater Res A|volume=64|issue=3|pages=540–50|doi=10.1002/jbm.a.10337|pmid=12579569}}</ref>膜の生体材料の生体適合性を高めるために、封入された細胞の、増殖や分化の程度を制御するペプチドおよびタンパク質分子を用い、カプセルの表面を修飾することが研究されている。アミノ酸配列Arg-Gly-Asp(RGD)でアルギン酸ヒドロゲルを修飾することで、細胞の挙動が、その結合したRGDの濃度によって制御できるとの報告がある。<ref>{{Cite journal|year=2002|title=Alginate type and RGD density control myoblast phenotype|journal=Journal of Biomedical Materials Research|volume=60|issue=2|pages=217–223|doi=10.1002/jbm.1287}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|year=2008|title=Quantifying the relation between bond number and myoblast proliferation|journal=Faraday Discussions|volume=139|pages=57-30|doi=10.1039/B719928G}}</ref>臨床応用における、細胞のマイクロカプセルのもう1つの重要な要素は、アルギン酸を修飾し免疫適合性をもたせ、免疫から保護することである。ポリ-L-リシン(PLL)が修飾に利用されるが、その生体適合性は低く、炎症を誘引して、中の細胞は壊死し、臨床的な応用は難しい。<ref name="pmid12514721">{{Cite journal|date=January 2003|title=Cell encapsulation: promise and progress|journal=Nat. Med.|volume=9|issue=1|pages=104–7|doi=10.1038/nm0103-104|pmid=12514721}}</ref><ref name="pmid11437072">{{Cite journal|year=2001|title=Poly-l-lysine induces fibrosis on alginate microcapsules via the induction of cytokines|journal=Cell Transplant|volume=10|issue=3|pages=263–75|pmid=11437072}}</ref> アルギン酸-PLL-アルギン酸(APA)で修飾すると、マイクロカプセルは機械的な安定性が低く、短期間の耐久性しか示さない。ポリL-オルニチン<ref name="pmid10415570">{{Cite journal|date=June 1999|title=Transplantation of pancreatic islets contained in minimal volume microcapsules in diabetic high mammalians|journal=Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences|volume=875|pages=219–32|doi=10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08506.x|pmid=10415570}}</ref> 、やポリ(メチレン-グアニジン)塩酸塩(poly(methylene-co-guanidine) hydrochloride)<ref name="pmid9094138">{{Cite journal|date=April 1997|title=An encapsulation system for the immunoisolation of pancreatic islets|journal=Nat. Biotechnol.|volume=15|issue=4|pages=358–62|doi=10.1038/nbt0497-358|pmid=9094138}}</ref> を用いると、細胞の機械的強度が高く制御された耐久性のあるカプセル化細胞ができ、有望だという報告がある。 |

||

いくつかのグループは、細胞を包むためのマイクロカプセルを製造するため、PLLの代替物として、天然に由来するキトサンを使用し、アルギン酸 - キトサン(AC)のマイクロカプセルの研究している。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=March 2005|title=In vitro study of alginate-chitosan microcapsules: an alternative to liver cell transplants for the treatment of liver failure|journal=Biotechnol. Lett.|volume=27|issue=5|pages=317–22| |

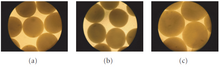

いくつかのグループは、細胞を包むためのマイクロカプセルを製造するため、PLLの代替物として、天然に由来するキトサンを使用し、アルギン酸 - キトサン(AC)のマイクロカプセルの研究している。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=March 2005|title=In vitro study of alginate-chitosan microcapsules: an alternative to liver cell transplants for the treatment of liver failure|journal=Biotechnol. Lett.|volume=27|issue=5|pages=317–22|doi=10.1007/s10529-005-0687-3|pmid=15834792}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|date=April 2005|title=Biomineralized polysaccharide capsules for encapsulation, organization, and delivery of human cell types and growth factors|journal=Advanced Functional Materials|volume=15|issue=6|pages=917–923|doi=10.1002/adfm.200400322}}</ref> しかしながら、このAC膜にも、安定性について問題があると示されている。<ref name="Chen H, Ouyang W, Jones M, et al. 2007 159–68">{{cite journal|year=2007|title=Preparation and characterization of novel polymeric microcapsules for live cell encapsulation and therapy|url=|journal=Cell Biochem. Biophys.|volume=47|issue=1|pages=159–68|vauthors=Chen H, Ouyang W, Jones M|pmid=17406068|doi=10.1385/cbb:47:1:159|display-authors=etal}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|date=August 2004|title=The influence of coating materials on some properties of alginate beads and survivability of microencapsulated probiotic bacteria|journal=International Dairy Journal|volume=14|issue=8|pages=737–743|doi=10.1016/j.idairyj.2004.01.004}}</ref> 結合したアルギン酸 - キトサン(GCAC)マイクロカプセルは、細胞を充填したマイクロカプセルの安定性を高めることができる。<ref name="Chen H, Ouyang W, Jones M, et al. 2007 159–68">{{cite journal|year=2007|title=Preparation and characterization of novel polymeric microcapsules for live cell encapsulation and therapy|url=|journal=Cell Biochem. Biophys.|volume=47|issue=1|pages=159–68|vauthors=Chen H, Ouyang W, Jones M|pmid=17406068|doi=10.1385/cbb:47:1:159|display-authors=etal}}</ref> |

||

[[ファイル:AC_microcapsule_microphotographs.png|代替文=Microphotographs of the alginate-chitosan (AC) microcapsules.|サムネイル|[[アルギン酸]]-[[キトサン]] (AC)マイクロカプセルの顕微鏡写真。]] |

[[ファイル:AC_microcapsule_microphotographs.png|代替文=Microphotographs of the alginate-chitosan (AC) microcapsules.|サムネイル|[[アルギン酸]]-[[キトサン]] (AC)マイクロカプセルの顕微鏡写真。]] |

||

==== コラーゲン ==== |

==== コラーゲン ==== |

||

細胞外マトリックスの主要なタンパク質成分である[[コラーゲン]]は、皮膚、軟骨、骨、血管および靭帯のような組織の強度を提供し、生体適合性、生分解性、および細胞との結合能力をもつために、組織工学において、細胞の、足場またはマトリックスの代表だと考えられている。。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=March 2000|title=collagen-based biomaterials as 3D scaffold for cell cultures: applications for tissue engineering and gene therapy|journal=Med Biol Eng Comput|volume=38|issue=2|pages=211–8| |

細胞外マトリックスの主要なタンパク質成分である[[コラーゲン]]は、皮膚、軟骨、骨、血管および靭帯のような組織の強度を提供し、生体適合性、生分解性、および細胞との結合能力をもつために、組織工学において、細胞の、足場またはマトリックスの代表だと考えられている。。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=March 2000|title=collagen-based biomaterials as 3D scaffold for cell cultures: applications for tissue engineering and gene therapy|journal=Med Biol Eng Comput|volume=38|issue=2|pages=211–8|doi=10.1007/bf02344779|pmid=10829416}}</ref> したがって、動物組織から得られたI型コラーゲンは、今や、組織工学で生体材料として複数の用途に使え、さかんに商業的に使用されている。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=May 2007|title=Natural-origin polymers as carriers and scaffolds for biomolecules and cell delivery in tissue engineering applications|journal=Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.|volume=59|issue=4-5|pages=207–33|doi=10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.012|pmid=17482309}}</ref> コラーゲンはまた、神経修復<ref>{{Cite journal|date=August 1997|title=Axonal regrowth through collagen tubes bridging the spinal cord to nerve roots|journal=J. Neurosci. Res.|volume=49|issue=4|pages=425–32|doi=10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19970815)49:4<425::AID-JNR4>3.0.CO;2-A|pmid=9285519}}</ref> 、および膀胱工学においても使用されている。<ref name="pmid9094138">{{Cite journal|date=April 1997|title=An encapsulation system for the immunoisolation of pancreatic islets|journal=Nat. Biotechnol.|volume=15|issue=4|pages=358–62|doi=10.1038/nbt0497-358|pmid=9094138}}</ref> しかし、コラーゲンには抗原性があり、コラーゲンの応用が制限される。そのため、ゼラチンが代替可能であると考えられている。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=May 2007|title=Surface engineered and drug releasing pre-fabricated scaffolds for tissue engineering|journal=Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.|volume=59|issue=4-5|pages=249–62|doi=10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.015|pmid=17482310}}</ref> |

||

==== ゼラチン ==== |

==== ゼラチン ==== |

||

[[ゼラチン]]は、コラーゲンを変性させ調製される。ゼラチンは、生分解性、生体適合性、生理学的環境における非免疫原性、および加工が容易であるなどの多くの望ましい性質があり、組織工学の用途に適している。それは、皮膚、骨および軟骨などの組織を工学的に作製するときに使用され、皮膚を置換するために商業的に使用される。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=December 2005|title=Gelatin as a delivery vehicle for the controlled release of bioactive molecules|journal=J Control Release|volume=109|issue=1-3|pages=256–74| |

[[ゼラチン]]は、コラーゲンを変性させ調製される。ゼラチンは、生分解性、生体適合性、生理学的環境における非免疫原性、および加工が容易であるなどの多くの望ましい性質があり、組織工学の用途に適している。それは、皮膚、骨および軟骨などの組織を工学的に作製するときに使用され、皮膚を置換するために商業的に使用される。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=December 2005|title=Gelatin as a delivery vehicle for the controlled release of bioactive molecules|journal=J Control Release|volume=109|issue=1-3|pages=256–74|doi=10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.023|pmid=16266768}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal|date=November 2002|title=Loading of collagen-heparan sulfate matrices with bFGF promotes angiogenesis and tissue generation in rats|journal=J. Biomed. Mater. Res.|volume=62|issue=2|pages=185–94|doi=10.1002/jbm.10267|pmid=12209938}}</ref> |

||

==== キトサン ==== |

==== キトサン ==== |

||

[[キトサン]] は多糖類である。ドラッグデリバリー、<ref>{{Cite journal|year=1997|title=[[chitosan]] microcapsules as controlled release systems for insulin|journal=J Microencapsul|volume=14|issue=5|pages=567–76| |

[[キトサン]] は多糖類である。ドラッグデリバリー、<ref>{{Cite journal|year=1997|title=[[chitosan]] microcapsules as controlled release systems for insulin|journal=J Microencapsul|volume=14|issue=5|pages=567–76|doi=10.3109/02652049709006810|pmid=9292433}}</ref> 生体の空間充填をする素材<ref>{{Cite journal|date=May 1988|title=Biological activity of chitosan: ultrastructural study|journal=Biomaterials|volume=9|issue=3|pages=247–52|doi=10.1016/0142-9612(88)90092-0|pmid=3408796}}</ref> および創傷の治療に使う包帯としてなど、複数の用途に使用されている。。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=July 2010|title=Physical, antibacterial and antioxidant properties of chitosan films incorporated with thyme oil for potential wound healing applications|journal=J Mater Sci Mater Med|volume=21|issue=7|pages=2227–36|doi=10.1007/s10856-010-4065-x|pmid=20372985}}</ref> キトサンの欠点は、機械的に弱いことである。そのため、しばしばコラーゲンなどの他のポリマーと組み合わされて、カプセル化細胞の用途として、強い機械的特性をもつポリマーとして使われる。。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=April 2001|title=Evaluation of nanostructured composite collagen--chitosan matrices for tissue engineering|journal=Tissue Eng.|volume=7|issue=2|pages=203–10|doi=10.1089/107632701300062831|pmid=11304455}}</ref> |

||

==== アガロース ==== |

==== アガロース ==== |

||

[[アガロース]] は、細胞のナノカプセル化に用いられる海藻由来の多糖であり、細胞とアガロース懸濁液<ref name="pubs.rsc.org">Venkat Chokkalingam, Jurjen Tel, Florian Wimmers, Xin Liu, Sergey Semenov, Julian Thiele, Carl G. Figdor, Wilhelm T.S. Huck, Probing cellular heterogeneity in cytokine-secreting immune cells using droplet-based microfluidics, Lab on a Chip, 13, 4740-4744, 2013, DOI: 10.1039/C3LC50945A, http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2013/lc/c3lc50945a#!divAbstract</ref> を、調製中に温度を低下させ、マイクロビーズを形成することができる。 。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=November 2001|title=Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers|journal=Science|volume=294|issue=5547|pages=1684–8| |

[[アガロース]] は、細胞のナノカプセル化に用いられる海藻由来の多糖であり、細胞とアガロース懸濁液<ref name="pubs.rsc.org">Venkat Chokkalingam, Jurjen Tel, Florian Wimmers, Xin Liu, Sergey Semenov, Julian Thiele, Carl G. Figdor, Wilhelm T.S. Huck, Probing cellular heterogeneity in cytokine-secreting immune cells using droplet-based microfluidics, Lab on a Chip, 13, 4740-4744, 2013, DOI: 10.1039/C3LC50945A, http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2013/lc/c3lc50945a#!divAbstract</ref> を、調製中に温度を低下させ、マイクロビーズを形成することができる。 。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=November 2001|title=Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers|journal=Science|volume=294|issue=5547|pages=1684–8|doi=10.1126/science.1063187|pmid=11721046}}</ref> しかし、この方法で得られたマイクロビーズには、カプセルの壁から細胞が突き出してしまうという欠点がある。 |

||

==== 硫酸セルロース ==== |

==== 硫酸セルロース ==== |

||

硫酸セルロースは綿から調整され、生体適合性の素材として使用することができる。ゲル化させ、細胞を懸濁させると、細胞の周囲に半透膜を形成できる。哺乳類の細胞株および細菌のいずれに使用しても細胞は生き残り、カプセル内で増殖を続ける。他のカプセル化材料とは対照的に、このカプセルでは、細胞を成長させることができるため、ミニバイオリアクターのように機能する。材料の生体適合性は、細胞充填カプセルの移植や、カプセル自体を用いた研究での観察によって実証されている。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Dautzenberg|first=H|date=Jun 18, 1999|title=Development of cellulose sulfate-based polyelectrolyte complex microcapsules for medical applications.|journal=Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences|volume=875|pages=46–63| |

硫酸セルロースは綿から調整され、生体適合性の素材として使用することができる。ゲル化させ、細胞を懸濁させると、細胞の周囲に半透膜を形成できる。哺乳類の細胞株および細菌のいずれに使用しても細胞は生き残り、カプセル内で増殖を続ける。他のカプセル化材料とは対照的に、このカプセルでは、細胞を成長させることができるため、ミニバイオリアクターのように機能する。材料の生体適合性は、細胞充填カプセルの移植や、カプセル自体を用いた研究での観察によって実証されている。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Dautzenberg|first=H|date=Jun 18, 1999|title=Development of cellulose sulfate-based polyelectrolyte complex microcapsules for medical applications.|journal=Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences|volume=875|pages=46–63|doi=10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08493.x|pmid=10415557}}</ref> 硫酸セルロースから形成されたカプセルは、主として抗癌治療として、また遺伝子療法や抗体療法としての使用も検討され、ヒトおよび動物の、臨床および前臨床試験において、安全性および有効性を示している。。<ref name="Löhr 393–8">{{cite journal|last=Löhr|first=M|date=April 1999|title=Cell therapy using microencapsulated 293 cells transfected with a gene construct expressing CYP2B1, an ifosfamide converting enzyme, instilled intra-arterially in patients with advanced-stage pancreatic carcinoma: a phase I/II study.|journal=Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany)|volume=77|issue=4|pages=393–8|author2=Bago, ZT|author3=Bergmeister, H|author4=Ceijna, M|author5=Freund, M|author6=Gelbmann, W|author7=Günzburg, WH|author8=Jesnowski, R|author9=Hain, J|author10=Hauenstein, K|author11=Henninger, W|author12=Hoffmeyer, A|author13=Karle, P|author14=Kröger, JC|author15=Kundt, G|author16=Liebe, S|author17=Losert, U|author18=Müller, P|author19=Probst, A|author20=Püschel, K|author21=Renner, M|author22=Renz, R|author23=Saller, R|author24=Salmons, B|author25=Walter, I|pmid=10353444|doi=10.1007/s001090050366}}</ref><ref name="Pelegrin 828–34">{{cite journal|last=Pelegrin|first=M|date=June 1998|title=Systemic long-term delivery of antibodies in immunocompetent animals using cellulose sulphate capsules containing antibody-producing cells.|journal=Gene therapy|volume=5|issue=6|pages=828–34|author2=Marin, M|author3=Noël, D|author4=Del Rio, M|author5=Saller, R|author6=Stange, J|author7=Mitzner, S|author8=Günzburg, WH|author9=Piechaczyk, M|pmid=9747463|doi=10.1038/sj.gt.3300632}}</ref><ref name="Pelegrin 1407–15">{{cite journal|last=Pelegrin|first=M|date=Jul 1, 2000|title=Immunotherapy of a viral disease by in vivo production of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies.|journal=Human gene therapy|volume=11|issue=10|pages=1407–15|author2=Marin, M|author3=Oates, A|author4=Noël, D|author5=Saller, R|author6=Salmons, B|author7=Piechaczyk, M|pmid=10910138|doi=10.1089/10430340050057486}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Armeanu|first=S|date=Jul–Aug 2001|title=In vivo perivascular implantation of encapsulated packaging cells for prolonged retroviral gene transfer.|journal=Journal of microencapsulation|volume=18|issue=4|pages=491–506|doi=10.1080/02652040010018047|pmid=11428678}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Winiarczyk|first=S|date=September 2002|title=A clinical protocol for treatment of canine mammary tumors using encapsulated, cytochrome P450 synthesizing cells activating cyclophosphamide: a phase I/II study.|journal=Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany)|volume=80|issue=9|pages=610–4|doi=10.1007/s00109-002-0356-0|pmid=12226743}}</ref> 硫酸セルロースを使用したカプセル化細胞を大量生産し、Good Manufacturing Process(cGMP)の基準を満たした医薬品が、2007年にオーストリアの企業によって商業化された。。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Salmons|first=B|year=2007|title=GMP production of an encapsulated cell therapy product: issues and considerations|url=http://www.bioprocessingjournal.com/index.php/past-issues?start=6|journal=BioProcessing Journal|volume=6|issue=2|pages=37–44}}</ref> |

||

=== 生体適合性 === |

=== 生体適合性 === |

||

この技術においては、生体適合性の特性をもつ理想的な高品質の生体材料が、長期的な効率を左右する最も重要な要因である。カプセル化細胞のための理想的な生体材料は、完全に生体適合性であり、宿主内で免疫応答を誘発せず、高い細胞の生存率を確実にするために細胞の恒常性を妨害しないものでなければならない。<ref>{{Cite book|last=Rabanel|first=Michel|title=ACS Symposium Series, Vol. 934|date=June 2006|publisher=American Chemical Society|ISBN=978-0-8412-3960-9|pages=305–309|chapter=Polysaccharide Hydrogels for the Preparation of Immunoisolated Cell Delivery Systems|last2=Nicolas Bertrand|author2=Nicolas Bertrand|last3=Shilpa Sant|author3=Shilpa Sant|last4=Salma Louati|author4=Salma Louati|last5=Patrice Hildgen|author5=Patrice Hildgen}}</ref><ref name="pubs.rsc.org">Venkat Chokkalingam, Jurjen Tel, Florian Wimmers, Xin Liu, Sergey Semenov, Julian Thiele, Carl G. Figdor, Wilhelm T.S. Huck, Probing cellular heterogeneity in cytokine-secreting immune cells using droplet-based microfluidics, Lab on a Chip, 13, 4740-4744, 2013, DOI: 10.1039/C3LC50945A, http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2013/lc/c3lc50945a#!divAbstract</ref><ref name="pmid18724374">{{Cite journal|date=October 2008|title=Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells|journal=Nat Mater|volume=7|issue=10|pages=816–23| |

この技術においては、生体適合性の特性をもつ理想的な高品質の生体材料が、長期的な効率を左右する最も重要な要因である。カプセル化細胞のための理想的な生体材料は、完全に生体適合性であり、宿主内で免疫応答を誘発せず、高い細胞の生存率を確実にするために細胞の恒常性を妨害しないものでなければならない。<ref>{{Cite book|last=Rabanel|first=Michel|title=ACS Symposium Series, Vol. 934|date=June 2006|publisher=American Chemical Society|ISBN=978-0-8412-3960-9|pages=305–309|chapter=Polysaccharide Hydrogels for the Preparation of Immunoisolated Cell Delivery Systems|last2=Nicolas Bertrand|author2=Nicolas Bertrand|last3=Shilpa Sant|author3=Shilpa Sant|last4=Salma Louati|author4=Salma Louati|last5=Patrice Hildgen|author5=Patrice Hildgen}}</ref><ref name="pubs.rsc.org">Venkat Chokkalingam, Jurjen Tel, Florian Wimmers, Xin Liu, Sergey Semenov, Julian Thiele, Carl G. Figdor, Wilhelm T.S. Huck, Probing cellular heterogeneity in cytokine-secreting immune cells using droplet-based microfluidics, Lab on a Chip, 13, 4740-4744, 2013, DOI: 10.1039/C3LC50945A, http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2013/lc/c3lc50945a#!divAbstract</ref><ref name="pmid18724374">{{Cite journal|date=October 2008|title=Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells|journal=Nat Mater|volume=7|issue=10|pages=816–23|doi=10.1038/nmat2269|pmid=18724374|pmc=2929915}}</ref><ref name="pmid19344677">{{Cite journal|date=May 2009|title=Bioactive cell-hydrogel microcapsules for cell-based drug delivery|journal=J Control Release|volume=135|issue=3|pages=203–10|doi=10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.01.005|pmid=19344677}}</ref><ref name="pmid17058213">{{Cite journal|date=March 2007|title=Zeta-potentials of alginate-PLL capsules: a predictive measure for biocompatibility?|journal=J Biomed Mater Res A|volume=80|issue=4|pages=813–9|doi=10.1002/jbm.a.30979|pmid=17058213}}</ref> |

||

=== マイクロカプセルの透過性 === |

=== マイクロカプセルの透過性 === |

||

カプセル化細胞を包むカプセルに使う半透膜については、分子の透過性を調整する必要がある。<ref name="pmid14757043">{{Cite journal|date=February 2004|title=History, challenges and perspectives of cell microencapsulation|journal=Trends Biotechnol.|volume=22|issue=2|pages=87–92| |

カプセル化細胞を包むカプセルに使う半透膜については、分子の透過性を調整する必要がある。<ref name="pmid14757043">{{Cite journal|date=February 2004|title=History, challenges and perspectives of cell microencapsulation|journal=Trends Biotechnol.|volume=22|issue=2|pages=87–92|doi=10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.11.004|pmid=14757043}}</ref><ref name="pmid19551901">{{Cite journal|year=2009|title=Progress technology in microencapsulation methods for cell therapy|journal=Biotechnol. Prog.|volume=25|issue=4|pages=946–63|doi=10.1002/btpr.226|pmid=19551901}}</ref> 細胞のマイクロカプセルは、均一な厚さで設計され、細胞の生存に必要なカプセルに入る分子の速度、およびカプセルの膜から出る治療のための生成物や廃棄物の速度の、両方を制御する必要がある。包まれた細胞の免疫からの防護について考えると、免疫細胞だけでなく、抗体やサイトカインも、マイクロカプセルへの侵入を防ぐべきで、カプセルの膜の透過性の問題に取り組む際に留意しなければならない重要なポイントである。<ref name="pmid19551901">{{Cite journal|year=2009|title=Progress technology in microencapsulation methods for cell therapy|journal=Biotechnol. Prog.|volume=25|issue=4|pages=946–63|doi=10.1002/btpr.226|pmid=19551901}}</ref> |

||

異なる細胞タイプは異なる代謝要求をもつので、膜に封入された細胞のタイプに応じて、膜の透過性を最適化しなければならないことが示されている。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=August 2000|title=Technology of mammalian cell encapsulation|journal=Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.|volume=42|issue=1-2|pages=29–64| |

異なる細胞タイプは異なる代謝要求をもつので、膜に封入された細胞のタイプに応じて、膜の透過性を最適化しなければならないことが示されている。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=August 2000|title=Technology of mammalian cell encapsulation|journal=Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.|volume=42|issue=1-2|pages=29–64|doi=10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00053-3|pmid=10942814}}</ref> いくつかのグループが細胞のマイクロカプセルの膜透過性の研究しており<ref name="pmid18724374">{{Cite journal|date=October 2008|title=Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells|journal=Nat Mater|volume=7|issue=10|pages=816–23|doi=10.1038/nmat2269|pmid=18724374|pmc=2929915}}</ref><ref name="pmid19344677">{{Cite journal|date=May 2009|title=Bioactive cell-hydrogel microcapsules for cell-based drug delivery|journal=J Control Release|volume=135|issue=3|pages=203–10|doi=10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.01.005|pmid=19344677}}</ref>酸素のような特定の必須の要素の透過性の役割は示されているが、<ref name="pmid7719442">{{Cite journal|year=1995|title=Mathematical modelling of immobilized animal cell growth|journal=Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol|volume=23|issue=1|pages=109–33|doi=10.3109/10731199509117672|pmid=7719442}}</ref> 各細胞のタイプによる透過性の要件はまだ決定されていない。 |

||

=== 機械的強度と耐久性 === |

=== 機械的強度と耐久性 === |

||

マイクロカプセルは、栄養素および廃棄物の交換などにおける、物理的な、浸透圧のストレスに耐えるのに十分な膜強度(機械的安定性)を有することが必須である。カプセル封入された細胞の免疫拒絶につながる可能性があるため、移植時に破裂してはならないため、マイクロカプセルは十分に強くなければならない。<ref name="pmid19551901">{{Cite journal|year=2009|title=Progress technology in microencapsulation methods for cell therapy|journal=Biotechnol. Prog.|volume=25|issue=4|pages=946–63| |

マイクロカプセルは、栄養素および廃棄物の交換などにおける、物理的な、浸透圧のストレスに耐えるのに十分な膜強度(機械的安定性)を有することが必須である。カプセル封入された細胞の免疫拒絶につながる可能性があるため、移植時に破裂してはならないため、マイクロカプセルは十分に強くなければならない。<ref name="pmid19551901">{{Cite journal|year=2009|title=Progress technology in microencapsulation methods for cell therapy|journal=Biotechnol. Prog.|volume=25|issue=4|pages=946–63|doi=10.1002/btpr.226|pmid=19551901}}</ref> 例えば、異種移植の場合、同種移植と比較してより厳密でより安定した膜が必要とされるであろう。また、胆汁酸加水分解酵素(BSH)を過剰産生する活性ラクトバチルスプランタラム80細胞を包んだAPAマイクロカプセルを経口投与するための試験として、模擬的に胃腸管のモデルを使用し調べ、マイクロカプセルの機械的な強度や形状の変化を評価した。 APAマイクロカプセルは、生きた細菌の経口投与に使える可能性が高いことが示された。<ref>{{Cite journal|year=2007|title=Investigation of microencapsulated BSH active Lactobacillus in the simulated human GI tract|journal=J. Biomed. Biotechnol.|volume=2007|issue=7|pages=13684|doi=10.1155/2007/13684|pmid=18273409|pmc=2217584}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal|year=2010|title=Investigation of genipin Cross-Linked Microcapsule for oral Delivery of Live bacterial Cells and Other Biotherapeutics: Preparation and In Vitro Analysis in Simulated Human Gastrointestinal Model|journal=International Journal of Polymer Science|volume=2010|pages=1–10|doi=10.1155/2010/985137}}</ref> 血清コレステロールを低下させるために、経口投与する細菌充填カプセルの実験もされている。カプセルは、ヒトの胃腸管を模した管を通して、カプセルが体内でうまく生き残るかが調べられた。このように、細胞のマイクロカプセル化の機械的な特性に関しては、幅広い研究が必要である。マイクロカプセルの耐久性は、特に長時間にわたる治療剤の持続放出が必要な、生体内への適用のために必要である。 |

||

[[ファイル:AP_microcapsule_integrity,_GI_simulated_transit.png|代替文=Illustration of the APA microcapsule integrity and morphological changes during simulated GI transit. (a) Pre-stomach transit. (b) Post-stomach transit (60 minutes). (c) Post-stomach (60 minutes) and intestinal (10-hour) transit. Microcapsule size: (a) 608 ± 36 μm (b) 544 ± 40 μm (c) 725 ± 55 μm.|中央|サムネイル|APAマイクロカプセルの胃を通過する前後の形態学的な変化。(a)胃の通過前。 (b)胃の通過後(60分)。(c)胃(60分)および腸(10時間)の通過。 マイクロカプセルサイズ:(a)608±36µm(b)544±40µm(c)725±55µm。 Martoni et al. (2007)]] |

[[ファイル:AP_microcapsule_integrity,_GI_simulated_transit.png|代替文=Illustration of the APA microcapsule integrity and morphological changes during simulated GI transit. (a) Pre-stomach transit. (b) Post-stomach transit (60 minutes). (c) Post-stomach (60 minutes) and intestinal (10-hour) transit. Microcapsule size: (a) 608 ± 36 μm (b) 544 ± 40 μm (c) 725 ± 55 μm.|中央|サムネイル|APAマイクロカプセルの胃を通過する前後の形態学的な変化。(a)胃の通過前。 (b)胃の通過後(60分)。(c)胃(60分)および腸(10時間)の通過。 マイクロカプセルサイズ:(a)608±36µm(b)544±40µm(c)725±55µm。 Martoni et al. (2007)]] |

||

=== マイクロカプセルのサイズ === |

=== マイクロカプセルのサイズ === |

||

<font style="background-color: rgb(255, 255, 255);">マイクロカプセルの直径は、細胞マイクロカプセルに対する免疫応答ならびにカプセル膜を横切る物質輸送の両方に影響を及ぼす重要な因子である。小さいカプセルへの細胞応答は、より大きなカプセル</font><ref name="pmid16680700">{{Cite journal|date=August 2006|title=Biocompatibility of subsieve-size capsules versus conventional-size microcapsules|journal=J Biomed Mater Res A|volume=78|issue=2|pages=394–8| |

<font style="background-color: rgb(255, 255, 255);">マイクロカプセルの直径は、細胞マイクロカプセルに対する免疫応答ならびにカプセル膜を横切る物質輸送の両方に影響を及ぼす重要な因子である。小さいカプセルへの細胞応答は、より大きなカプセル</font><ref name="pmid16680700">{{Cite journal|date=August 2006|title=Biocompatibility of subsieve-size capsules versus conventional-size microcapsules|journal=J Biomed Mater Res A|volume=78|issue=2|pages=394–8|doi=10.1002/jbm.a.30676|pmid=16680700}}</ref> と比較してはるかに少なく、一般に、半透膜を横切る効果的な拡散を可能にするために、細胞が装填されたマイクロカプセルの直径は350-450μmでなければならないという報告もある。<ref name="pmid15603828">{{Cite journal|date=June 2005|title=Size control of calcium alginate beads containing living cells using micro-nozzle array|journal=Biomaterials|volume=26|issue=16|pages=3327–31|doi=10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.08.029|pmid=15603828}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|year=1998|title=Microencapsulation: a review of polymers and technologies with a focus on bioartificial organs|journal=Polimery|volume=43|pages=530–539}}</ref> |

||

=== 細胞の選択 === |

=== 細胞の選択 === |

||

細胞マイクロカプセルを何に使うかによって、使う細胞のタイプは変わる。カプセルに入れられた細胞は、患者由来(自己細胞)、別のドナー(同種異系細胞)または他の種(異種細胞)由来であってもよい。<ref name="pmid12767713">{{Cite journal|date=May 2003|title=Cell microencapsulation technology for biomedical purposes: novel insights and challenges|journal=Trends Pharmacol. Sci.|volume=24|issue=5|pages=207–10| |

細胞マイクロカプセルを何に使うかによって、使う細胞のタイプは変わる。カプセルに入れられた細胞は、患者由来(自己細胞)、別のドナー(同種異系細胞)または他の種(異種細胞)由来であってもよい。<ref name="pmid12767713">{{Cite journal|date=May 2003|title=Cell microencapsulation technology for biomedical purposes: novel insights and challenges|journal=Trends Pharmacol. Sci.|volume=24|issue=5|pages=207–10|doi=10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00073-7|pmid=12767713}}</ref> 自己細胞の使用は、細胞によっては入手困難な場合がある。異種細胞は容易に入手可能であるが、ウイルス、特にブタは内在性レトロウイルスがあり、患者への感染の危険性が臨床への適用を制限している。<ref name="pmid10782067">{{Cite journal|date=May 2000|title=Xenotransplantation: is the risk of viral infection as great as we thought?|journal=Mol Med Today|volume=6|issue=5|pages=199–208|doi=10.1016/s1357-4310(00)01708-1|pmid=10782067}}</ref> いくつかの研究グループは、異種細胞の代わりに同種異系の使用が必要であると結論づけている。。<ref name="pmid11797662">{{Cite journal|last=Hunkeler D|author=Hunkeler D|date=November 2001|title=Allo transplants xeno: as bioartificial organs move to the clinic. Introduction|journal=Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences|volume=944|pages=1–6|doi=10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03818.x|pmid=11797662}}</ref> 用途に応じて、細胞を遺伝的に改変し、必要なタンパク質を発現させることもできる。<ref name="pmid10837651">{{Cite journal|date=August 1998|title=Development of engineered cells for implantation in gene therapy|journal=Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.|volume=33|issue=1-2|pages=31–43|doi=10.1016/S0169-409X(98)00018-0|pmid=10837651}}</ref> |

||

ただ、この技術は、カプセルに充填された細胞の高い免疫原性のために、臨床試験の承認を得ていない。それらは、サイトカインを分泌し、カプセル周囲の移植部位で重度の炎症反応を引き起こし、カプセル化細胞の生存率を低下させる。<ref name="pmid16574222">{{Cite journal|date=July 2006|title=Biocompatibility of alginate-poly-l-lysine microcapsules for cell therapy|journal=Biomaterials|volume=27|issue=20|pages=3691–700| |

ただ、この技術は、カプセルに充填された細胞の高い免疫原性のために、臨床試験の承認を得ていない。それらは、サイトカインを分泌し、カプセル周囲の移植部位で重度の炎症反応を引き起こし、カプセル化細胞の生存率を低下させる。<ref name="pmid16574222">{{Cite journal|date=July 2006|title=Biocompatibility of alginate-poly-l-lysine microcapsules for cell therapy|journal=Biomaterials|volume=27|issue=20|pages=3691–700|doi=10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.048|pmid=16574222}}</ref><ref name="pmid15313388">{{Cite journal|date=September 2004|title=Causes of limited survival of microencapsulated pancreatic islet grafts|journal=J. Surg. Res.|volume=121|issue=1|pages=141–50|doi=10.1016/j.jss.2004.02.018|pmid=15313388}}</ref> 一的に研究されているの抗炎症薬の削減への免疫応答の制作による管理は、細胞搭載マイクロカプセルです。<ref name="pmid16701881">{{Cite journal|date=March 2006|title=Biocompatibility and function of microencapsulated pancreatic islets|journal=Acta Biomater|volume=2|issue=2|pages=221–7|doi=10.1016/j.actbio.2005.12.002|pmid=16701881}}</ref><ref name="pmid15585238">{{Cite journal|date=May 2005|title=Deletion of the tissue response against alginate-pll capsules by temporary release of co-encapsulated steroids|journal=Biomaterials|volume=26|issue=15|pages=2353–60|doi=10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.017|pmid=15585238}}</ref> このため、細胞療法の用途のための間葉系幹細胞などの幹細胞の使用が研究されている。。<ref name="pmid19726759">{{Cite journal|date=January 2010|title=Encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells: a unique hypoimmunogenic platform for long-term cellular therapy|journal=FASEB J.|volume=24|issue=1|pages=22–31|doi=10.1096/fj.09-131888|pmid=19726759}}</ref> マイクロカプセル化された細胞の長期の生存を損なう別の問題は、最終的にカプセルいっぱいに細胞が分裂して、半透膜を横切る拡散が低下する。<ref name="pmid10837651">{{Cite journal|date=August 1998|title=Development of engineered cells for implantation in gene therapy|journal=Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.|volume=33|issue=1-2|pages=31–43|doi=10.1016/S0169-409X(98)00018-0|pmid=10837651}}</ref> これに対する解決策のひとつとしては、マイクロカプセル化の後に増殖しない筋芽細胞などの細胞の使用が考えられる。 |

||

== 医療以外への応用 == |

== 医療以外への応用 == |

||

[[プロバイオティクス]] は、健康のために、アイスクリーム、ヨーグルト、乳製品のデザート、チーズなど、多くの乳製品など、日常の食品に取り入れられている。しかし、食品中のプロバイオティックの細菌は、生存率が低い。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=January 1997|title=Viability of yoghurt and probiotic bacteria in yoghurts made from commercial starter cultures|journal=International Dairy Journal|volume=7|issue=1|pages=31–41| |

[[プロバイオティクス]] は、健康のために、アイスクリーム、ヨーグルト、乳製品のデザート、チーズなど、多くの乳製品など、日常の食品に取り入れられている。しかし、食品中のプロバイオティックの細菌は、生存率が低い。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=January 1997|title=Viability of yoghurt and probiotic bacteria in yoghurts made from commercial starter cultures|journal=International Dairy Journal|volume=7|issue=1|pages=31–41|doi=10.1016/S0958-6946(96)00046-5}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|year=1996|title=Effect of whey protein concentrate on the survival of lactobacillus acidophilus in lactose hydrolysed yoghurt during refrigerated storage|journal=Milchwissenschaft|volume=51|pages=565–569}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|year=1996|title=Survival of Bifidobacteria during refrigerated storage in the presence of acid and hydrogen peroxide|journal=Milchwissenschaft|volume=51|pages=65–70}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite news|title=Health and nutritional properties of probiotics in food including powder milk with live lactic acid bacteria|newspaper=FAO/WHO Experts’ Report|accessdate=20 November 2010|publisher=FAQ/WHO}}</ref> <font style="background-color: rgb(255, 255, 255);">細菌は、製造された食品で安定で、消化管を通って移動する間も生存し、宿主の腸に到達すると効果をもたらす必要がある</font>。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Gilliland SE|author=Gilliland SE|date=October 1989|title=Acidophilus milk products: a review of potential benefits to consumers|journal=J. Dairy Sci.|volume=72|issue=10|pages=2483–94|doi=10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(89)79389-9|pmid=2513349}}</ref> |

||

細胞のマイクロカプセル化技術は、プロバイオティック食品で、細菌をカプセル化し、乳製品の加工、胃腸管の移動において、細菌の生存率を高めるために、適用され成功している。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=May 2007|title=Recent advances in microencapsulation of probiotics for industrial applications and targeted delivery|journal=Trends in Food Science & Technology|volume=18|issue=5|pages=240–251| |

細胞のマイクロカプセル化技術は、プロバイオティック食品で、細菌をカプセル化し、乳製品の加工、胃腸管の移動において、細菌の生存率を高めるために、適用され成功している。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=May 2007|title=Recent advances in microencapsulation of probiotics for industrial applications and targeted delivery|journal=Trends in Food Science & Technology|volume=18|issue=5|pages=240–251|doi=10.1016/j.tifs.2007.01.004}}</ref> |

||

== 医療への応用 == |

== 医療への応用 == |

||

=== 糖尿病 === |

=== 糖尿病 === |

||

半透膜で膵島細胞をカプセル化し、糖尿病の治療のための人工膵臓として使用する可能性は、科学者によって広く研究されている。これらのカプセルが実現できれば、臓器ドナーの不足の問題を最終的に解決することに加えて、免疫抑制薬の必要性を排除することができる。マイクロカプセルは、膵島細胞を免疫拒絶から保護するので、動物細胞または遺伝子改変インスリン産生細胞の使用を可能にする。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=December 2005|title=The bioartificial pancreas: progress and challenges|journal=Diabetes Technol. Ther.|volume=7|issue=6|pages=968–85| |

半透膜で膵島細胞をカプセル化し、糖尿病の治療のための人工膵臓として使用する可能性は、科学者によって広く研究されている。これらのカプセルが実現できれば、臓器ドナーの不足の問題を最終的に解決することに加えて、免疫抑制薬の必要性を排除することができる。マイクロカプセルは、膵島細胞を免疫拒絶から保護するので、動物細胞または遺伝子改変インスリン産生細胞の使用を可能にする。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=December 2005|title=The bioartificial pancreas: progress and challenges|journal=Diabetes Technol. Ther.|volume=7|issue=6|pages=968–85|doi=10.1089/dia.2005.7.968|pmid=16386103}}</ref> これらの膵島のマイクロカプセルの開発により、1型糖尿病患者に1日数回必要とされるインスリン注射が不要になると期待されている。<ref name="pmid12767713">{{Cite journal|date=May 2003|title=Cell microencapsulation technology for biomedical purposes: novel insights and challenges|journal=Trends Pharmacol. Sci.|volume=24|issue=5|pages=207–10|doi=10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00073-7|pmid=12767713}}</ref> <ref name="pmid10911004">{{Cite journal|date=July 2000|title=Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen|journal=N. Engl. J. Med.|volume=343|issue=4|pages=230–8|doi=10.1056/NEJM200007273430401|pmid=10911004}}</ref> |

||

この目的に向けた最初の試みは、1980年にLimらによってなされた。<ref name="pmid6776628">{{Cite journal|date=November 1980|title=Microencapsulated islets as bioartificial endocrine pancreas|journal=Science|volume=210|issue=4472|pages=908–10| |

この目的に向けた最初の試みは、1980年にLimらによってなされた。<ref name="pmid6776628">{{Cite journal|date=November 1980|title=Microencapsulated islets as bioartificial endocrine pancreas|journal=Science|volume=210|issue=4472|pages=908–10|doi=10.1126/science.6776628|pmid=6776628}}</ref> |

||

ポリマー性のカプセル内でランゲルハンス島を包んだ人工膵臓の開発に向けて、いくつかの研究がされている。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=June 2000|title=Improved post-cryopreservation recovery following encapsulation of islets in chitosan-alginate microcapsules|journal=Transplant. Proc.|volume=32|issue=4|pages=824–5| |

ポリマー性のカプセル内でランゲルハンス島を包んだ人工膵臓の開発に向けて、いくつかの研究がされている。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=June 2000|title=Improved post-cryopreservation recovery following encapsulation of islets in chitosan-alginate microcapsules|journal=Transplant. Proc.|volume=32|issue=4|pages=824–5|doi=10.1016/s0041-1345(00)00995-7|pmid=10856598}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal|year=1999|title=In vitro and in vivo performance of porcine islets encapsulated in interfacially photopolymerized polyethylene glycol diacrylate membranes|journal=Cell Transplant|volume=8|issue=3|pages=293–306|pmid=10442742}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal|date=February 2003|title=Protection of NOD islet isograft from autoimmune destruction by agarose microencapsulation|journal=Transplant. Proc.|volume=35|issue=1|pages=484–5|doi=10.1016/S0041-1345(02)03829-0|pmid=12591496}}</ref> マイクロカプセル化されたヒトの膵島を用いた臨床試験が行われている。 2003年にパイロットフェーズ1臨床試験が、膵島細胞を含有するアルギン酸/ PLOマイクロカプセルの使用で、イタリア保健省のペルージャ大学で実施された。<ref name="pmid14757043">{{Cite journal|date=February 2004|title=History, challenges and perspectives of cell microencapsulation|journal=Trends Biotechnol.|volume=22|issue=2|pages=87–92|doi=10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.11.004|pmid=14757043}}</ref> Novocellによって2005年に、皮下部位への膵島の同種異系移植のフェーズI / IIの臨床試験が開始された。<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.clinicaltrials.gov|title=Clinical trial information|accessdate=21 November 2010}}</ref> Living Cell technologies Ltdによる、9年半の間免疫抑制剤を使用せずに、移植された機能をもつ異種細胞の生存を実証したヒト臨床試験もあった。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=March 2007|title=Live encapsulated porcine islets from a type 1 diabetic patient 9.5 yr after xenotransplantation|journal=Xenotransplantation|volume=14|issue=2|pages=157–61|doi=10.1111/j.1399-3089.2007.00384.x|pmid=17381690}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Grose S|author=Grose S|date=April 2007|title=Critics slam Russian trial to test pig pancreas for diabetics|journal=Nat. Med.|volume=13|issue=4|pages=390–1|doi=10.1038/nm0407-390b|pmid=17415358}}</ref>臨床試験が進行中であり、生体適合性や免疫保護などのいくつかの主要な問題を克服する必要がある。<ref>{{Cite journal|date=February 2002|title=Considerations for successful transplantation of encapsulated pancreatic islets|journal=Diabetologia|volume=45|issue=2|pages=159–73|doi=10.1007/s00125-001-0729-x|pmid=11935147}}</ref> |

||

硫酸セルロースを用いて膵島細胞がカプセル化され、細胞が生存し、グルコースに応答してインスリンを放出することが実証された。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Stadlbauer|first=V|date=July 2006|title=Morphological and functional characterization of a pancreatic beta-cell line microencapsulated in sodium cellulose sulfate/poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride).|journal=Xenotransplantation|volume=13|issue=4|pages=337–44| |

硫酸セルロースを用いて膵島細胞がカプセル化され、細胞が生存し、グルコースに応答してインスリンを放出することが実証された。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Stadlbauer|first=V|date=July 2006|title=Morphological and functional characterization of a pancreatic beta-cell line microencapsulated in sodium cellulose sulfate/poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride).|journal=Xenotransplantation|volume=13|issue=4|pages=337–44|doi=10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00315.x|pmid=16768727}}</ref> 前臨床試験で、移植されたカプセル化細胞は糖尿病ラットの血糖値を6ヶ月間回復させることができた。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Steigler|first=P|year=2009|title=Xenotransplantation of NaCS microencapsulated porcine islet cells in diabetic rats|url=https://mol.medicalonline.jp/archive/search?jo=ca3organ&ye=2009&vo=16&issue=1|journal=Organ Biology|volume=16|issue=1|pages=104}}</ref> |

||

=== がん === |

=== がん === |

||

いくつかの種類のがんの治療に、カプセル化細胞が使える可能性も示されている。1つのアプローチは、遺伝子改変されたサイトカイン分泌細胞を含むマイクロカプセルの移植である。この例は、Cironeらによって、マウスに移植された、遺伝的に改変されたIL-2サイトカインを分泌する非自己由来のマウス筋芽細胞が、生存率の上げ腫瘍増殖の遅延を示した。<ref name="pmid12133269">{{Cite journal|date=July 2002|title=A novel approach to tumor suppression with microencapsulated recombinant cells|journal=Hum. Gene Ther.|volume=13|issue=10|pages=1157–66| |

いくつかの種類のがんの治療に、カプセル化細胞が使える可能性も示されている。1つのアプローチは、遺伝子改変されたサイトカイン分泌細胞を含むマイクロカプセルの移植である。この例は、Cironeらによって、マウスに移植された、遺伝的に改変されたIL-2サイトカインを分泌する非自己由来のマウス筋芽細胞が、生存率の上げ腫瘍増殖の遅延を示した。<ref name="pmid12133269">{{Cite journal|date=July 2002|title=A novel approach to tumor suppression with microencapsulated recombinant cells|journal=Hum. Gene Ther.|volume=13|issue=10|pages=1157–66|doi=10.1089/104303402320138943|pmid=12133269}}</ref> しかし、移植されたマイクロカプセルに対する免疫応答のために、この治療の効果は短かった。がん抑制の別のアプローチは、腫瘍の増殖を起こす成長因子を防ぐ血管形成阻害剤の使用によるものである。腫瘍細胞にアポトーシスを起こさせるエンドスタチンという血管形成を阻害するタンパク質があり、それを分泌するように遺伝子改変された異種細胞をマイクロカプセル化し、それを移植する効果は、広範に研究されている。<ref name="pmid11135549">{{Cite journal|date=January 2001|title=Continuous release of endostatin from microencapsulated engineered cells for tumor therapy|journal=Nat. Biotechnol.|volume=19|issue=1|pages=35–9|doi=10.1038/83481|pmid=11135549}}</ref><ref name="pmid11135548">{{Cite journal|date=January 2001|title=Local endostatin treatment of gliomas administered by microencapsulated producer cells|journal=Nat. Biotechnol.|volume=19|issue=1|pages=29–34|doi=10.1038/83471|pmid=11135548}}</ref> <ref name="pmid17417683">{{Cite journal|date=April 2007|title=Inhibition of tumor growth in mice by endostatin derived from abdominal transplanted encapsulated cells|journal=Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai)|volume=39|issue=4|pages=278–84|doi=10.1111/j.1745-7270.2007.00273.x|pmid=17417683}}</ref><ref name="pmid12885346">{{Cite journal|date=July 2003|title=Antiangiogenic cancer therapy with microencapsulated cells|journal=Hum. Gene Ther.|volume=14|issue=11|pages=1065–77|doi=10.1089/104303403322124783|pmid=12885346}}</ref> |

||

1998年に、膵臓がんのマウスのモデルを用いて、腫瘍の治療のために硫酸セルロースでカプセル化された遺伝子改変シトクロムP450発現ネコ上皮細胞を移植する効果を研究した。<ref name="pmid10026857">{{Cite journal|year=1998|title=Intratumoral injection of encapsulated cells producing an oxazaphosphorine activating cytochrome P450 for targeted chemotherapy|journal=Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.|volume=451|pages=97–106| |

1998年に、膵臓がんのマウスのモデルを用いて、腫瘍の治療のために硫酸セルロースでカプセル化された遺伝子改変シトクロムP450発現ネコ上皮細胞を移植する効果を研究した。<ref name="pmid10026857">{{Cite journal|year=1998|title=Intratumoral injection of encapsulated cells producing an oxazaphosphorine activating cytochrome P450 for targeted chemotherapy|journal=Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.|volume=451|pages=97–106|doi=10.1007/978-1-4615-5357-1_16|pmid=10026857}}</ref> このアプローチは、化学療法剤を[[プロドラッグ]]として投与し、P450で活性化させるものだが、化学療法剤の活性化酵素を発現した細胞の応用の、初めての試みだった。これらの結果に基づいて、カプセル化細胞であるNovaCapsを膵臓がん患者治療として第I / IIフェーズの臨床試験が行われ<ref name="pmid11377651">{{Cite journal|date=May 2001|title=Microencapsulated cell-mediated treatment of inoperable pancreatic carcinoma|journal=Lancet|volume=357|issue=9268|pages=1591–2|doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04749-8|pmid=11377651}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|year=2003|title=Safety, feasibility and clinical benefit of localized chemotherapy using microencapsulated cells for inoperable pancreatic carcinoma in a phase I/II trial|journal=Ccancer Ther|volume=1|pages=121–131}}</ref> 現在では、欧州医薬品局(EMEA)[[希少疾病用医薬品]]として欧州で認められている。同じ製品を使用ったさらなる第I / IIフェーズの臨床試験が行われ、膵臓がん第4ステージの患者の生存期間が2倍になった第一の臨床試験の結果を確認した。。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lam|first=P|date=March 2013|title=The innovative evolution of cancer gene and cellular therapies.|journal=Cancer gene therapy|volume=20|issue=3|pages=141–9|doi=10.1038/cgt.2012.93|pmid=23370333}}</ref> 明確な抗腫瘍効果に加えて、硫酸セルロースのカプセルは十分に耐久性があり、カプセルに対する免疫応答などの有害反応は見られず、硫酸セルロースカプセルの生体適合性を実証した。患者の一人では、2年間カプセルの副作用はなかった。 |

||

これらの研究は、がんの治療への細胞マイクロカプセルの有望な潜在性を示している。<ref name="pubs.rsc.org">Venkat Chokkalingam, Jurjen Tel, Florian Wimmers, Xin Liu, Sergey Semenov, Julian Thiele, Carl G. Figdor, Wilhelm T.S. Huck, Probing cellular heterogeneity in cytokine-secreting immune cells using droplet-based microfluidics, Lab on a Chip, 13, 4740-4744, 2013, DOI: 10.1039/C3LC50945A, http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2013/lc/c3lc50945a#!divAbstract</ref> しかし、より多くの臨床試験の前に、カプセルの移植部位の周囲組織への炎症を引き起こす免疫応答の問題を解決しなければならない。 |

これらの研究は、がんの治療への細胞マイクロカプセルの有望な潜在性を示している。<ref name="pubs.rsc.org">Venkat Chokkalingam, Jurjen Tel, Florian Wimmers, Xin Liu, Sergey Semenov, Julian Thiele, Carl G. Figdor, Wilhelm T.S. Huck, Probing cellular heterogeneity in cytokine-secreting immune cells using droplet-based microfluidics, Lab on a Chip, 13, 4740-4744, 2013, DOI: 10.1039/C3LC50945A, http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2013/lc/c3lc50945a#!divAbstract</ref> しかし、より多くの臨床試験の前に、カプセルの移植部位の周囲組織への炎症を引き起こす免疫応答の問題を解決しなければならない。 |

||

=== 心臓病 === |

=== 心臓病 === |

||

虚血性心疾患の患者における心臓組織再生の有効な治療法開発に向けて、多くの研究がなされている。虚血性の組織損傷の修復に、幹細胞が利用されている。<ref>{{Cite journal|year=2007|title=Cell therapy in myocardial infarction|journal=Cardiovasc Revasc Med|volume=8|issue=1|pages=43–51| |

虚血性心疾患の患者における心臓組織再生の有効な治療法開発に向けて、多くの研究がなされている。虚血性の組織損傷の修復に、幹細胞が利用されている。<ref>{{Cite journal|year=2007|title=Cell therapy in myocardial infarction|journal=Cardiovasc Revasc Med|volume=8|issue=1|pages=43–51|doi=10.1016/j.carrev.2006.11.005|pmid=17293268}}</ref> しかし、幹細胞に基づく治療が心臓機能に発生的な効果をもつ実際のメカニズムは依然として研究中である。多数の方法が細胞投与のために研究されているが、移植後に、鼓動する心臓に保持されうる細胞の数の効率は依然として非常に低い。この問題を克服するための有望なアプローチは、遊離幹細胞の心臓への注入と比較して高い細胞保持を可能にすることを示したマイクロカプセル化細胞の使用によるものである。<ref name="pmid19761398">{{Cite journal|date=September 2009|title=Microencapsulated stem cells for tissue repairing: implications in cell-based myocardial therapy|journal=Regen Med|volume=4|issue=5|pages=733–45|doi=10.2217/rme.09.43|pmid=19761398}}</ref> |

||

心臓再生へのカプセル化細胞の技術の別の戦略は、血管新生を刺激することである。損傷した虚血性心臓の血流を回復させる血管内皮増殖因子(VEGF)のような血管新生因子を分泌することができる遺伝子改変幹細胞を使用する。<ref name="pmid15778410">{{Cite journal|last=Madeddu P|author=Madeddu P|date=May 2005|title=Therapeutic angiogenesis and vasculogenesis for tissue regeneration|journal=Exp. Physiol.|volume=90|issue=3|pages=315–26| |

心臓再生へのカプセル化細胞の技術の別の戦略は、血管新生を刺激することである。損傷した虚血性心臓の血流を回復させる血管内皮増殖因子(VEGF)のような血管新生因子を分泌することができる遺伝子改変幹細胞を使用する。<ref name="pmid15778410">{{Cite journal|last=Madeddu P|author=Madeddu P|date=May 2005|title=Therapeutic angiogenesis and vasculogenesis for tissue regeneration|journal=Exp. Physiol.|volume=90|issue=3|pages=315–26|doi=10.1113/EXPPHYSIOL.2004.028571|pmid=15778410}}</ref><ref name="pmid18061883">{{Cite journal|last=Jacobs J|author=Jacobs J|date=December 2007|title=Combating cardiovascular disease with angiogenic therapy|journal=Drug Discov. Today|volume=12|issue=23-24|pages=1040–5|doi=10.1016/j.drudis.2007.08.018|pmid=18061883}}</ref> <font style="background-color: rgb(255, 255, 255);">この一例がZangらの研究に示されている。その研究では、VEGFを発現するように遺伝的に改変されたマウスの細胞が、マイクロカプセルに封入され、ラット心筋に移植された</font>。<ref name="pmid17943144">{{Cite journal|date=January 2008|title=Transplantation of microencapsulated genetically modified xenogeneic cells augments angiogenesis and improves heart function|journal=Gene Ther.|volume=15|issue=1|pages=40–8|doi=10.1038/sj.gt.3303049|pmid=17943144}}</ref><ref name="pmid17943144">{{Cite journal|date=January 2008|title=Transplantation of microencapsulated genetically modified xenogeneic cells augments angiogenesis and improves heart function|journal=Gene Ther.|volume=15|issue=1|pages=40–8|doi=10.1038/sj.gt.3303049|pmid=17943144}}</ref> カプセル化は、3週間、免疫細胞から細胞を保護し、血管新生の増加による心筋組織後梗塞の改善にもつながったことが観察された。 |

||

=== モノクローナル抗体療法 === |

=== モノクローナル抗体療法 === |

||

| 96行目: | 96行目: | ||

=== その他 === |

=== その他 === |

||

カプセル化細胞を使った治療法としては、多くの病状が標的とされている。最も成功したアプローチの1つは、透析装置と同様に作用する外部装置であり、血液注入チューブの半透性部分にブタの肝細胞を取り込んだものである。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bonavita|first=AG|date=May–June 2010|title=Hepatocyte xenotransplantation for treating liver disease|journal=Xenotransplantation|volume=17|issue=3|pages=181–187| |

カプセル化細胞を使った治療法としては、多くの病状が標的とされている。最も成功したアプローチの1つは、透析装置と同様に作用する外部装置であり、血液注入チューブの半透性部分にブタの肝細胞を取り込んだものである。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bonavita|first=AG|date=May–June 2010|title=Hepatocyte xenotransplantation for treating liver disease|journal=Xenotransplantation|volume=17|issue=3|pages=181–187|doi=10.1111/j.1399-3089.2010.00588.x|pmid=20636538}}</ref> この装置は、重度の肝不全を患っている患者の血液から毒素を除去することができる。依然として開発中の他の応用には、ALSおよびハンチントン病の治療のための毛様体由来神経栄養因子、パーキンソン病のグリア由来神経栄養因子、貧血のためのエリスロポエチンおよび小人症のためのHGHなどがある。<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lysaght|first=Micheal J.|date=April 1999|title=Encapsulated Cells as Therapy|journal=Scientific American|pages=76–82}}</ref> 加えて潜在的にだが、血友病、ゴーシェ病およびいくつかのムコ多糖類障害のような一元性疾患もまた、患者に欠けているタンパク質を発現するカプセル化細胞による治療法の開発が考え得る。 |

||

== 参考文献 == |

== 参考文献 == |

||

2020年1月25日 (土) 16:29時点における版

細胞のマイクロカプセル化技術は、ポリマーの半透膜で細胞を包み、細胞の移動を制限する技術である。その半透膜は、細胞代謝に必須の酸素、栄養素、成長因子などの分子の双方向の拡散は可能で、廃棄物および細胞が分泌する治療のためのタンパク質の外側への拡散は可能なものを使用する。同時に、膜は、カプセル内の細胞が外来の物質と認識され、免疫細胞や抗体によって、破壊されるのを防ぐ。

細胞のカプセル化技術の主な目的は、組織工学の用途として、移植片への拒絶反応の問題を克服し、臓器移植後の免疫抑制剤の長期使用の必要性を低減することである。

歴史

1933年にVincenzo Bisceglieは、ポリマーの膜に細胞をカプセル化する最初の試みを行った。彼は、ブタの腹腔に移植されたポリマー膜の中の腫瘍細胞は、免疫系によって拒絶されることなく、長期間生存可能であることを実証した。[1]

30年後の1964年に、超薄型高分子膜のマイクロカプセル内に細胞を封入することで、細胞に免疫に対しての防御を与えるというアイデアが、Thomas Changによって提案された。[2] カプセル化された細胞は、免疫拒絶から保護されるだけでなく、体積に対する表面積が大きくなり、それが酸素と栄養素の良好な移動を可能にすることも、示唆している。[2]20年後、このアプローチは、小動物をモデルにし、実践された。すい臓のランゲルハンス島(膵島)の細胞を、アルギン酸塩 - ポリリジン - アルギン酸(APA)マイクロカプセルで、固定化し、異種間移植された。[3] この研究では、マイクロカプセル化したすい臓のランゲルハンス島を、糖尿病のラットに移植すると、細胞が生存し、数週間にわたって血糖を制御し続けたことを実証した。カプセル化された細胞を利用したヒトへの試験は1998年に実施された。[4][5][6] 進行性の切除不能なすい臓がんの臨床試験として、抗腫瘍効果を局所的に発揮するために、シトクロムP450酵素を発現するカプセル化細胞が腫瘍部位に移植され、シトクロムP450に分解されて抗腫瘍効果を発揮するプロドラッグが患者に投与された。対照と比較して約2倍の生存期間が示された。

組織工学と再生医療のためのツールとしての、細胞のマイクロカプセル化

細胞のカプセル化技術のメリットの1つめは、移植部位で、より長い期間にわたり、治療用物質を放出できることである。例えば、インスリンを毎食後注射しないといけない糖尿病に対して、カプセル化技術によるすい臓細胞を移植することで、インスリンを注射しi jなくてすむ。細胞のマイクロカプセル化技術のもう1つの利点は、適合するドナーがいない場合でも、ヒト以外の動物の細胞や、遺伝子改変細胞を、ポリマーでカプセル化することで使用可能になることである。[7] マイクロカプセルは、いろいろな組織や器官に移植することができ、局所的な治療も、経口投与もできる貴重な技術である。治療部位への薬物が届くまでの距離はふつうは長く、それに比べれば、カプセル化細胞の移植は直接薬物を届けるため、よりコストがかからない。さらに、患者の移植適合抗原を気にせず、同じカプセル化細胞を移植できれば、コストを低減できるだろう。[7]

細胞のマイクロカプセル化技術の要素

マイクロカプセル化細胞を臨床へ応用するために、開発の過程で次の要件を適切に選択する必要がある。機械的および化学的に安定な半透過性のマトリックスを形成するための適切な生体適合性ポリマーの使用、均一サイズのマイクロカプセルの製造、適切な免疫適合性のポリカチオンをカプセルとなるポリマーに架橋結合させてカプセルを安定化させる、状況に応じて適切な細胞のタイプを選択する、などのことが含まれる。ポリカチオンとは塩基性の解離基をそのモノマーにもつポリマーである。

生体材料

用途に応じた最善の生体材料が、ドラッグデリバリーシステムや組織工学の発展には重要である。アルギン酸のポリマーは、一般的に、古くから研究されてきており、容易に入手可能で、低コストである。それ以外のものだと、硫酸セルロース、コラーゲン、キトサン、ゼラチン、アガロースなどの材料も使用されてきた。

アルギン酸

いくつかの研究グループにより、細胞のマイクロカプセル化に最適な生体材料を開発することを目的として、いくつかの天然および合成の高分子が幅広く研究されてきた。[8][9] アルギン酸は、豊富に入手可能、優れた生体適合性、および生物分解性により、細胞のマイクロカプセル化に最も適した生体材料と見なされ、広範な研究がなされている。アルギン酸は、海藻および細菌[10] から抽出することができる天然ポリマーである。分離する元の素材に応じてさまざまな組成をもつ。[10]

アルギン酸も、いくつかの欠点があると指摘されている。高M含量のアルギン酸は炎症反応を引き起こし[11][12] 異常な細胞増殖を引き起こすと指摘されている。[13] [14][15] [16][17]超高純度のアルギン酸でさえ、エンドトキシンや、細胞のマイクロカプセルの生体適合性を損なう可能性のあるポリフェノールを含有している可能性がある。[15][18][19] 臨床用途に使用するためには、アルギン酸から不要な物質を除去できる、効果的な精製プロセスの設計が不可欠である。

アルギン酸の修飾と機能化

アルギン酸を修飾した、マイクロカプセルの開発もされている。[20][21]膜の生体材料の生体適合性を高めるために、封入された細胞の、増殖や分化の程度を制御するペプチドおよびタンパク質分子を用い、カプセルの表面を修飾することが研究されている。アミノ酸配列Arg-Gly-Asp(RGD)でアルギン酸ヒドロゲルを修飾することで、細胞の挙動が、その結合したRGDの濃度によって制御できるとの報告がある。[22][23]臨床応用における、細胞のマイクロカプセルのもう1つの重要な要素は、アルギン酸を修飾し免疫適合性をもたせ、免疫から保護することである。ポリ-L-リシン(PLL)が修飾に利用されるが、その生体適合性は低く、炎症を誘引して、中の細胞は壊死し、臨床的な応用は難しい。[24][25] アルギン酸-PLL-アルギン酸(APA)で修飾すると、マイクロカプセルは機械的な安定性が低く、短期間の耐久性しか示さない。ポリL-オルニチン[26] 、やポリ(メチレン-グアニジン)塩酸塩(poly(methylene-co-guanidine) hydrochloride)[27] を用いると、細胞の機械的強度が高く制御された耐久性のあるカプセル化細胞ができ、有望だという報告がある。

いくつかのグループは、細胞を包むためのマイクロカプセルを製造するため、PLLの代替物として、天然に由来するキトサンを使用し、アルギン酸 - キトサン(AC)のマイクロカプセルの研究している。[28][29] しかしながら、このAC膜にも、安定性について問題があると示されている。[30][31] 結合したアルギン酸 - キトサン(GCAC)マイクロカプセルは、細胞を充填したマイクロカプセルの安定性を高めることができる。[30]

コラーゲン

細胞外マトリックスの主要なタンパク質成分であるコラーゲンは、皮膚、軟骨、骨、血管および靭帯のような組織の強度を提供し、生体適合性、生分解性、および細胞との結合能力をもつために、組織工学において、細胞の、足場またはマトリックスの代表だと考えられている。。[32] したがって、動物組織から得られたI型コラーゲンは、今や、組織工学で生体材料として複数の用途に使え、さかんに商業的に使用されている。[33] コラーゲンはまた、神経修復[34] 、および膀胱工学においても使用されている。[27] しかし、コラーゲンには抗原性があり、コラーゲンの応用が制限される。そのため、ゼラチンが代替可能であると考えられている。[35]

ゼラチン

ゼラチンは、コラーゲンを変性させ調製される。ゼラチンは、生分解性、生体適合性、生理学的環境における非免疫原性、および加工が容易であるなどの多くの望ましい性質があり、組織工学の用途に適している。それは、皮膚、骨および軟骨などの組織を工学的に作製するときに使用され、皮膚を置換するために商業的に使用される。[36] [37]

キトサン

キトサン は多糖類である。ドラッグデリバリー、[38] 生体の空間充填をする素材[39] および創傷の治療に使う包帯としてなど、複数の用途に使用されている。。[40] キトサンの欠点は、機械的に弱いことである。そのため、しばしばコラーゲンなどの他のポリマーと組み合わされて、カプセル化細胞の用途として、強い機械的特性をもつポリマーとして使われる。。[41]

アガロース

アガロース は、細胞のナノカプセル化に用いられる海藻由来の多糖であり、細胞とアガロース懸濁液[42] を、調製中に温度を低下させ、マイクロビーズを形成することができる。 。[43] しかし、この方法で得られたマイクロビーズには、カプセルの壁から細胞が突き出してしまうという欠点がある。

硫酸セルロース

硫酸セルロースは綿から調整され、生体適合性の素材として使用することができる。ゲル化させ、細胞を懸濁させると、細胞の周囲に半透膜を形成できる。哺乳類の細胞株および細菌のいずれに使用しても細胞は生き残り、カプセル内で増殖を続ける。他のカプセル化材料とは対照的に、このカプセルでは、細胞を成長させることができるため、ミニバイオリアクターのように機能する。材料の生体適合性は、細胞充填カプセルの移植や、カプセル自体を用いた研究での観察によって実証されている。[44] 硫酸セルロースから形成されたカプセルは、主として抗癌治療として、また遺伝子療法や抗体療法としての使用も検討され、ヒトおよび動物の、臨床および前臨床試験において、安全性および有効性を示している。。[4][45][46][47][48] 硫酸セルロースを使用したカプセル化細胞を大量生産し、Good Manufacturing Process(cGMP)の基準を満たした医薬品が、2007年にオーストリアの企業によって商業化された。。[49]

生体適合性

この技術においては、生体適合性の特性をもつ理想的な高品質の生体材料が、長期的な効率を左右する最も重要な要因である。カプセル化細胞のための理想的な生体材料は、完全に生体適合性であり、宿主内で免疫応答を誘発せず、高い細胞の生存率を確実にするために細胞の恒常性を妨害しないものでなければならない。[50][42][51][52][53]

マイクロカプセルの透過性

カプセル化細胞を包むカプセルに使う半透膜については、分子の透過性を調整する必要がある。[54][55] 細胞のマイクロカプセルは、均一な厚さで設計され、細胞の生存に必要なカプセルに入る分子の速度、およびカプセルの膜から出る治療のための生成物や廃棄物の速度の、両方を制御する必要がある。包まれた細胞の免疫からの防護について考えると、免疫細胞だけでなく、抗体やサイトカインも、マイクロカプセルへの侵入を防ぐべきで、カプセルの膜の透過性の問題に取り組む際に留意しなければならない重要なポイントである。[55]

異なる細胞タイプは異なる代謝要求をもつので、膜に封入された細胞のタイプに応じて、膜の透過性を最適化しなければならないことが示されている。[56] いくつかのグループが細胞のマイクロカプセルの膜透過性の研究しており[51][52]酸素のような特定の必須の要素の透過性の役割は示されているが、[57] 各細胞のタイプによる透過性の要件はまだ決定されていない。

機械的強度と耐久性

マイクロカプセルは、栄養素および廃棄物の交換などにおける、物理的な、浸透圧のストレスに耐えるのに十分な膜強度(機械的安定性)を有することが必須である。カプセル封入された細胞の免疫拒絶につながる可能性があるため、移植時に破裂してはならないため、マイクロカプセルは十分に強くなければならない。[55] 例えば、異種移植の場合、同種移植と比較してより厳密でより安定した膜が必要とされるであろう。また、胆汁酸加水分解酵素(BSH)を過剰産生する活性ラクトバチルスプランタラム80細胞を包んだAPAマイクロカプセルを経口投与するための試験として、模擬的に胃腸管のモデルを使用し調べ、マイクロカプセルの機械的な強度や形状の変化を評価した。 APAマイクロカプセルは、生きた細菌の経口投与に使える可能性が高いことが示された。[58] [59] 血清コレステロールを低下させるために、経口投与する細菌充填カプセルの実験もされている。カプセルは、ヒトの胃腸管を模した管を通して、カプセルが体内でうまく生き残るかが調べられた。このように、細胞のマイクロカプセル化の機械的な特性に関しては、幅広い研究が必要である。マイクロカプセルの耐久性は、特に長時間にわたる治療剤の持続放出が必要な、生体内への適用のために必要である。

マイクロカプセルのサイズ

マイクロカプセルの直径は、細胞マイクロカプセルに対する免疫応答ならびにカプセル膜を横切る物質輸送の両方に影響を及ぼす重要な因子である。小さいカプセルへの細胞応答は、より大きなカプセル[60] と比較してはるかに少なく、一般に、半透膜を横切る効果的な拡散を可能にするために、細胞が装填されたマイクロカプセルの直径は350-450μmでなければならないという報告もある。[61][62]

細胞の選択

細胞マイクロカプセルを何に使うかによって、使う細胞のタイプは変わる。カプセルに入れられた細胞は、患者由来(自己細胞)、別のドナー(同種異系細胞)または他の種(異種細胞)由来であってもよい。[63] 自己細胞の使用は、細胞によっては入手困難な場合がある。異種細胞は容易に入手可能であるが、ウイルス、特にブタは内在性レトロウイルスがあり、患者への感染の危険性が臨床への適用を制限している。[64] いくつかの研究グループは、異種細胞の代わりに同種異系の使用が必要であると結論づけている。。[65] 用途に応じて、細胞を遺伝的に改変し、必要なタンパク質を発現させることもできる。[66]

ただ、この技術は、カプセルに充填された細胞の高い免疫原性のために、臨床試験の承認を得ていない。それらは、サイトカインを分泌し、カプセル周囲の移植部位で重度の炎症反応を引き起こし、カプセル化細胞の生存率を低下させる。[15][67] 一的に研究されているの抗炎症薬の削減への免疫応答の制作による管理は、細胞搭載マイクロカプセルです。[68][69] このため、細胞療法の用途のための間葉系幹細胞などの幹細胞の使用が研究されている。。[70] マイクロカプセル化された細胞の長期の生存を損なう別の問題は、最終的にカプセルいっぱいに細胞が分裂して、半透膜を横切る拡散が低下する。[66] これに対する解決策のひとつとしては、マイクロカプセル化の後に増殖しない筋芽細胞などの細胞の使用が考えられる。

医療以外への応用

プロバイオティクス は、健康のために、アイスクリーム、ヨーグルト、乳製品のデザート、チーズなど、多くの乳製品など、日常の食品に取り入れられている。しかし、食品中のプロバイオティックの細菌は、生存率が低い。[71][72][73] [74] 細菌は、製造された食品で安定で、消化管を通って移動する間も生存し、宿主の腸に到達すると効果をもたらす必要がある。[75]

細胞のマイクロカプセル化技術は、プロバイオティック食品で、細菌をカプセル化し、乳製品の加工、胃腸管の移動において、細菌の生存率を高めるために、適用され成功している。[76]

医療への応用

糖尿病

半透膜で膵島細胞をカプセル化し、糖尿病の治療のための人工膵臓として使用する可能性は、科学者によって広く研究されている。これらのカプセルが実現できれば、臓器ドナーの不足の問題を最終的に解決することに加えて、免疫抑制薬の必要性を排除することができる。マイクロカプセルは、膵島細胞を免疫拒絶から保護するので、動物細胞または遺伝子改変インスリン産生細胞の使用を可能にする。[77] これらの膵島のマイクロカプセルの開発により、1型糖尿病患者に1日数回必要とされるインスリン注射が不要になると期待されている。[63] [78]

この目的に向けた最初の試みは、1980年にLimらによってなされた。[3]

ポリマー性のカプセル内でランゲルハンス島を包んだ人工膵臓の開発に向けて、いくつかの研究がされている。[79] [80] [81] マイクロカプセル化されたヒトの膵島を用いた臨床試験が行われている。 2003年にパイロットフェーズ1臨床試験が、膵島細胞を含有するアルギン酸/ PLOマイクロカプセルの使用で、イタリア保健省のペルージャ大学で実施された。[54] Novocellによって2005年に、皮下部位への膵島の同種異系移植のフェーズI / IIの臨床試験が開始された。[82] Living Cell technologies Ltdによる、9年半の間免疫抑制剤を使用せずに、移植された機能をもつ異種細胞の生存を実証したヒト臨床試験もあった。[83][84]臨床試験が進行中であり、生体適合性や免疫保護などのいくつかの主要な問題を克服する必要がある。[85]

硫酸セルロースを用いて膵島細胞がカプセル化され、細胞が生存し、グルコースに応答してインスリンを放出することが実証された。[86] 前臨床試験で、移植されたカプセル化細胞は糖尿病ラットの血糖値を6ヶ月間回復させることができた。[87]

がん

いくつかの種類のがんの治療に、カプセル化細胞が使える可能性も示されている。1つのアプローチは、遺伝子改変されたサイトカイン分泌細胞を含むマイクロカプセルの移植である。この例は、Cironeらによって、マウスに移植された、遺伝的に改変されたIL-2サイトカインを分泌する非自己由来のマウス筋芽細胞が、生存率の上げ腫瘍増殖の遅延を示した。[88] しかし、移植されたマイクロカプセルに対する免疫応答のために、この治療の効果は短かった。がん抑制の別のアプローチは、腫瘍の増殖を起こす成長因子を防ぐ血管形成阻害剤の使用によるものである。腫瘍細胞にアポトーシスを起こさせるエンドスタチンという血管形成を阻害するタンパク質があり、それを分泌するように遺伝子改変された異種細胞をマイクロカプセル化し、それを移植する効果は、広範に研究されている。[89][90] [91][92]

1998年に、膵臓がんのマウスのモデルを用いて、腫瘍の治療のために硫酸セルロースでカプセル化された遺伝子改変シトクロムP450発現ネコ上皮細胞を移植する効果を研究した。[93] このアプローチは、化学療法剤をプロドラッグとして投与し、P450で活性化させるものだが、化学療法剤の活性化酵素を発現した細胞の応用の、初めての試みだった。これらの結果に基づいて、カプセル化細胞であるNovaCapsを膵臓がん患者治療として第I / IIフェーズの臨床試験が行われ[94][95] 現在では、欧州医薬品局(EMEA)希少疾病用医薬品として欧州で認められている。同じ製品を使用ったさらなる第I / IIフェーズの臨床試験が行われ、膵臓がん第4ステージの患者の生存期間が2倍になった第一の臨床試験の結果を確認した。。[96] 明確な抗腫瘍効果に加えて、硫酸セルロースのカプセルは十分に耐久性があり、カプセルに対する免疫応答などの有害反応は見られず、硫酸セルロースカプセルの生体適合性を実証した。患者の一人では、2年間カプセルの副作用はなかった。

これらの研究は、がんの治療への細胞マイクロカプセルの有望な潜在性を示している。[42] しかし、より多くの臨床試験の前に、カプセルの移植部位の周囲組織への炎症を引き起こす免疫応答の問題を解決しなければならない。

心臓病

虚血性心疾患の患者における心臓組織再生の有効な治療法開発に向けて、多くの研究がなされている。虚血性の組織損傷の修復に、幹細胞が利用されている。[97] しかし、幹細胞に基づく治療が心臓機能に発生的な効果をもつ実際のメカニズムは依然として研究中である。多数の方法が細胞投与のために研究されているが、移植後に、鼓動する心臓に保持されうる細胞の数の効率は依然として非常に低い。この問題を克服するための有望なアプローチは、遊離幹細胞の心臓への注入と比較して高い細胞保持を可能にすることを示したマイクロカプセル化細胞の使用によるものである。[98]

心臓再生へのカプセル化細胞の技術の別の戦略は、血管新生を刺激することである。損傷した虚血性心臓の血流を回復させる血管内皮増殖因子(VEGF)のような血管新生因子を分泌することができる遺伝子改変幹細胞を使用する。[99][100] この一例がZangらの研究に示されている。その研究では、VEGFを発現するように遺伝的に改変されたマウスの細胞が、マイクロカプセルに封入され、ラット心筋に移植された。[101][101] カプセル化は、3週間、免疫細胞から細胞を保護し、血管新生の増加による心筋組織後梗塞の改善にもつながったことが観察された。

モノクローナル抗体療法

がんや炎症性疾患の治療のために、現在、モノクローナル抗体が使われはじめている。 硫酸セルロースの技術を用いて、抗体産生ハイブリドーマ細胞をカプセル化し、カプセルから治療用の抗体が放出できる。[45][46]

その他

カプセル化細胞を使った治療法としては、多くの病状が標的とされている。最も成功したアプローチの1つは、透析装置と同様に作用する外部装置であり、血液注入チューブの半透性部分にブタの肝細胞を取り込んだものである。[102] この装置は、重度の肝不全を患っている患者の血液から毒素を除去することができる。依然として開発中の他の応用には、ALSおよびハンチントン病の治療のための毛様体由来神経栄養因子、パーキンソン病のグリア由来神経栄養因子、貧血のためのエリスロポエチンおよび小人症のためのHGHなどがある。[103] 加えて潜在的にだが、血友病、ゴーシェ病およびいくつかのムコ多糖類障害のような一元性疾患もまた、患者に欠けているタンパク質を発現するカプセル化細胞による治療法の開発が考え得る。

参考文献

- ^ Bisceglie V (1993). “Uber die antineoplastische Immunität; heterologe Einpflanzung von Tumoren in Hühner-embryonen”. Zeitschrift für Krebsforschung 40: 122–140. doi:10.1007/bf01636399.

- ^ a b Chang TM (October 1964). “Semipermeable microcapsules”. Science 146 (3643): 524–5. doi:10.1126/science.146.3643.524. PMID 14190240.

- ^ a b “Microencapsulated islets as bioartificial endocrine pancreas”. Science 210 (4472): 908–10. (November 1980). doi:10.1126/science.6776628. PMID 6776628.

- ^ a b Löhr, M; Bago, ZT; Bergmeister, H; Ceijna, M; Freund, M; Gelbmann, W; Günzburg, WH; Jesnowski, R et al. (April 1999). “Cell therapy using microencapsulated 293 cells transfected with a gene construct expressing CYP2B1, an ifosfamide converting enzyme, instilled intra-arterially in patients with advanced-stage pancreatic carcinoma: a phase I/II study.”. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany) 77 (4): 393–8. doi:10.1007/s001090050366. PMID 10353444.

- ^ Löhr, M (May 19, 2001). “Microencapsulated cell-mediated treatment of inoperable pancreatic carcinoma.”. Lancet 357 (9268): 1591–2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04749-8. PMID 11377651.

- ^ Lohr, M (2003). “Safety, feasibility and clinical benefit of localized chemotherapy using microencapsulated cells for inoperable pancreatic carcinoma in a phase I/II trial”. Cancer Therapy 1: 121–31.

- ^ a b “Cell microencapsulation technology: towards clinical application”. J Control Release 132 (2): 76–83. (December 2008). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.08.010. PMID 18789985.

- ^ “Development of mammalian cell-enclosing subsieve-size agarose capsules (<100 microm) for cell therapy”. Biomaterials 26 (23): 4786–92. (August 2005). doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.043. PMID 15763258.

- ^ “Towards a fully synthetic substitute of alginate: optimization of a thermal gelation/chemical cross-linking scheme ("tandem" gelation) for the production of beads and liquid-core capsules”. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 88 (6): 740–9. (December 2004). doi:10.1002/bit.20264. PMID 15532084.

- ^ a b “Isolation of alginate-producing mutants of Pseudomonas fluorescens, Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas mendocina”. J. Gen. Microbiol. 125 (1): 217–20. (July 1981). doi:10.1099/00221287-125-1-217. PMID 6801192.

- ^ “Induction of cytokine production from human monocytes stimulated with alginate”. J. Immunother. 10 (4): 286–91. (August 1991). doi:10.1097/00002371-199108000-00007. PMID 1931864.

- ^ “The involvement of CD14 in stimulation of cytokine production by uronic acid polymers”. Eur. J. Immunol. 23 (1): 255–61. (January 1993). doi:10.1002/eji.1830230140. PMID 7678226.

- ^ “An immunologic basis for the fibrotic reaction to implanted microcapsules”. Transplant. Proc. 23 (1 Pt 1): 758–9. (February 1991). PMID 1990681.

- ^ “The effect of capsule composition on the biocompatibility of alginate-poly-l-lysine capsules”. J Microencapsul 8 (2): 221–33. (1991). doi:10.3109/02652049109071490. PMID 1765902.

- ^ a b c “Biocompatibility of alginate-poly-l-lysine microcapsules for cell therapy”. Biomaterials 27 (20): 3691–700. (July 2006). doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.048. PMID 16574222.

- ^ “Effect of the alginate composition on the biocompatibility of alginate-polylysine microcapsules”. Biomaterials 18 (3): 273–8. (February 1997). doi:10.1016/S0142-9612(96)00135-4. PMID 9031730.

- ^ De Vos, Paul; R. van Schifgaarde (September 1999). “Biocompatibility issues”. In Kühtreiber, Willem M.; Lanza, Robert P.; Chick, William L.. Cell Encapsulation Technology and Therapeutics. Birkhäuser Boston. ISBN 978-0-8176-4010-1

- ^ “Evaluation of alginate purification methods: effect on polyphenol, endotoxin, and protein contamination”. J Biomed Mater Res A 76 (2): 243–51. (February 2006). doi:10.1002/jbm.a.30541. PMID 16265647.

- ^ “Impact of residual contamination on the biofunctional properties of purified alginates used for cell encapsulation”. Biomaterials 27 (8): 1296–305. (March 2006). doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.08.027. PMID 16154192.

- ^ “Improvement of the biocompatibility of alginate/poly-l-lysine/alginate microcapsules by the use of epimerized alginate as a coating”. J Biomed Mater Res A 64 (3): 533–9. (March 2003). doi:10.1002/jbm.a.10276. PMID 12579568.

- ^ “Microcapsules made by enzymatically tailored alginate”. J Biomed Mater Res A 64 (3): 540–50. (March 2003). doi:10.1002/jbm.a.10337. PMID 12579569.

- ^ “Alginate type and RGD density control myoblast phenotype”. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research 60 (2): 217–223. (2002). doi:10.1002/jbm.1287.

- ^ “Quantifying the relation between bond number and myoblast proliferation”. Faraday Discussions 139: 57-30. (2008). doi:10.1039/B719928G.

- ^ “Cell encapsulation: promise and progress”. Nat. Med. 9 (1): 104–7. (January 2003). doi:10.1038/nm0103-104. PMID 12514721.

- ^ “Poly-l-lysine induces fibrosis on alginate microcapsules via the induction of cytokines”. Cell Transplant 10 (3): 263–75. (2001). PMID 11437072.

- ^ “Transplantation of pancreatic islets contained in minimal volume microcapsules in diabetic high mammalians”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 875: 219–32. (June 1999). doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08506.x. PMID 10415570.

- ^ a b “An encapsulation system for the immunoisolation of pancreatic islets”. Nat. Biotechnol. 15 (4): 358–62. (April 1997). doi:10.1038/nbt0497-358. PMID 9094138.

- ^ “In vitro study of alginate-chitosan microcapsules: an alternative to liver cell transplants for the treatment of liver failure”. Biotechnol. Lett. 27 (5): 317–22. (March 2005). doi:10.1007/s10529-005-0687-3. PMID 15834792.

- ^ “Biomineralized polysaccharide capsules for encapsulation, organization, and delivery of human cell types and growth factors”. Advanced Functional Materials 15 (6): 917–923. (April 2005). doi:10.1002/adfm.200400322.

- ^ a b “Preparation and characterization of novel polymeric microcapsules for live cell encapsulation and therapy”. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 47 (1): 159–68. (2007). doi:10.1385/cbb:47:1:159. PMID 17406068.

- ^ “The influence of coating materials on some properties of alginate beads and survivability of microencapsulated probiotic bacteria”. International Dairy Journal 14 (8): 737–743. (August 2004). doi:10.1016/j.idairyj.2004.01.004.

- ^ “collagen-based biomaterials as 3D scaffold for cell cultures: applications for tissue engineering and gene therapy”. Med Biol Eng Comput 38 (2): 211–8. (March 2000). doi:10.1007/bf02344779. PMID 10829416.

- ^ “Natural-origin polymers as carriers and scaffolds for biomolecules and cell delivery in tissue engineering applications”. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 59 (4-5): 207–33. (May 2007). doi:10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.012. PMID 17482309.

- ^ “Axonal regrowth through collagen tubes bridging the spinal cord to nerve roots”. J. Neurosci. Res. 49 (4): 425–32. (August 1997). doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19970815)49:4<425::AID-JNR4>3.0.CO;2-A. PMID 9285519.

- ^ “Surface engineered and drug releasing pre-fabricated scaffolds for tissue engineering”. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 59 (4-5): 249–62. (May 2007). doi:10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.015. PMID 17482310.

- ^ “Gelatin as a delivery vehicle for the controlled release of bioactive molecules”. J Control Release 109 (1-3): 256–74. (December 2005). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.023. PMID 16266768.

- ^ “Loading of collagen-heparan sulfate matrices with bFGF promotes angiogenesis and tissue generation in rats”. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 62 (2): 185–94. (November 2002). doi:10.1002/jbm.10267. PMID 12209938.

- ^ “chitosan microcapsules as controlled release systems for insulin”. J Microencapsul 14 (5): 567–76. (1997). doi:10.3109/02652049709006810. PMID 9292433.

- ^ “Biological activity of chitosan: ultrastructural study”. Biomaterials 9 (3): 247–52. (May 1988). doi:10.1016/0142-9612(88)90092-0. PMID 3408796.

- ^ “Physical, antibacterial and antioxidant properties of chitosan films incorporated with thyme oil for potential wound healing applications”. J Mater Sci Mater Med 21 (7): 2227–36. (July 2010). doi:10.1007/s10856-010-4065-x. PMID 20372985.

- ^ “Evaluation of nanostructured composite collagen--chitosan matrices for tissue engineering”. Tissue Eng. 7 (2): 203–10. (April 2001). doi:10.1089/107632701300062831. PMID 11304455.

- ^ a b c Venkat Chokkalingam, Jurjen Tel, Florian Wimmers, Xin Liu, Sergey Semenov, Julian Thiele, Carl G. Figdor, Wilhelm T.S. Huck, Probing cellular heterogeneity in cytokine-secreting immune cells using droplet-based microfluidics, Lab on a Chip, 13, 4740-4744, 2013, DOI: 10.1039/C3LC50945A, http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2013/lc/c3lc50945a#!divAbstract

- ^ “Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers”. Science 294 (5547): 1684–8. (November 2001). doi:10.1126/science.1063187. PMID 11721046.

- ^ Dautzenberg, H (Jun 18, 1999). “Development of cellulose sulfate-based polyelectrolyte complex microcapsules for medical applications.”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 875: 46–63. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08493.x. PMID 10415557.

- ^ a b Pelegrin, M; Marin, M; Noël, D; Del Rio, M; Saller, R; Stange, J; Mitzner, S; Günzburg, WH et al. (June 1998). “Systemic long-term delivery of antibodies in immunocompetent animals using cellulose sulphate capsules containing antibody-producing cells.”. Gene therapy 5 (6): 828–34. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3300632. PMID 9747463.

- ^ a b Pelegrin, M; Marin, M; Oates, A; Noël, D; Saller, R; Salmons, B; Piechaczyk, M (Jul 1, 2000). “Immunotherapy of a viral disease by in vivo production of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies.”. Human gene therapy 11 (10): 1407–15. doi:10.1089/10430340050057486. PMID 10910138.

- ^ Armeanu, S (Jul–Aug 2001). “In vivo perivascular implantation of encapsulated packaging cells for prolonged retroviral gene transfer.”. Journal of microencapsulation 18 (4): 491–506. doi:10.1080/02652040010018047. PMID 11428678.

- ^ Winiarczyk, S (September 2002). “A clinical protocol for treatment of canine mammary tumors using encapsulated, cytochrome P450 synthesizing cells activating cyclophosphamide: a phase I/II study.”. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany) 80 (9): 610–4. doi:10.1007/s00109-002-0356-0. PMID 12226743.

- ^ Salmons, B (2007). “GMP production of an encapsulated cell therapy product: issues and considerations”. BioProcessing Journal 6 (2): 37–44.

- ^ Rabanel, Michel; Nicolas Bertrand; Shilpa Sant; Salma Louati; Patrice Hildgen (June 2006). “Polysaccharide Hydrogels for the Preparation of Immunoisolated Cell Delivery Systems”. ACS Symposium Series, Vol. 934. American Chemical Society. pp. 305–309. ISBN 978-0-8412-3960-9

- ^ a b “Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells”. Nat Mater 7 (10): 816–23. (October 2008). doi:10.1038/nmat2269. PMC 2929915. PMID 18724374.

- ^ a b “Bioactive cell-hydrogel microcapsules for cell-based drug delivery”. J Control Release 135 (3): 203–10. (May 2009). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.01.005. PMID 19344677.

- ^ “Zeta-potentials of alginate-PLL capsules: a predictive measure for biocompatibility?”. J Biomed Mater Res A 80 (4): 813–9. (March 2007). doi:10.1002/jbm.a.30979. PMID 17058213.

- ^ a b “History, challenges and perspectives of cell microencapsulation”. Trends Biotechnol. 22 (2): 87–92. (February 2004). doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.11.004. PMID 14757043.

- ^ a b c “Progress technology in microencapsulation methods for cell therapy”. Biotechnol. Prog. 25 (4): 946–63. (2009). doi:10.1002/btpr.226. PMID 19551901.

- ^ “Technology of mammalian cell encapsulation”. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 42 (1-2): 29–64. (August 2000). doi:10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00053-3. PMID 10942814.

- ^ “Mathematical modelling of immobilized animal cell growth”. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol 23 (1): 109–33. (1995). doi:10.3109/10731199509117672. PMID 7719442.

- ^ “Investigation of microencapsulated BSH active Lactobacillus in the simulated human GI tract”. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2007 (7): 13684. (2007). doi:10.1155/2007/13684. PMC 2217584. PMID 18273409.

- ^ “Investigation of genipin Cross-Linked Microcapsule for oral Delivery of Live bacterial Cells and Other Biotherapeutics: Preparation and In Vitro Analysis in Simulated Human Gastrointestinal Model”. International Journal of Polymer Science 2010: 1–10. (2010). doi:10.1155/2010/985137.

- ^ “Biocompatibility of subsieve-size capsules versus conventional-size microcapsules”. J Biomed Mater Res A 78 (2): 394–8. (August 2006). doi:10.1002/jbm.a.30676. PMID 16680700.

- ^ “Size control of calcium alginate beads containing living cells using micro-nozzle array”. Biomaterials 26 (16): 3327–31. (June 2005). doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.08.029. PMID 15603828.

- ^ “Microencapsulation: a review of polymers and technologies with a focus on bioartificial organs”. Polimery 43: 530–539. (1998).

- ^ a b “Cell microencapsulation technology for biomedical purposes: novel insights and challenges”. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 24 (5): 207–10. (May 2003). doi:10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00073-7. PMID 12767713.

- ^ “Xenotransplantation: is the risk of viral infection as great as we thought?”. Mol Med Today 6 (5): 199–208. (May 2000). doi:10.1016/s1357-4310(00)01708-1. PMID 10782067.

- ^ Hunkeler D (November 2001). “Allo transplants xeno: as bioartificial organs move to the clinic. Introduction”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 944: 1–6. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03818.x. PMID 11797662.

- ^ a b “Development of engineered cells for implantation in gene therapy”. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 33 (1-2): 31–43. (August 1998). doi:10.1016/S0169-409X(98)00018-0. PMID 10837651.

- ^ “Causes of limited survival of microencapsulated pancreatic islet grafts”. J. Surg. Res. 121 (1): 141–50. (September 2004). doi:10.1016/j.jss.2004.02.018. PMID 15313388.