利用者:あるうぃんす/翻訳:Languages of Europe

|

ここはあるうぃんすさんの利用者サンドボックスです。編集を試したり下書きを置いておいたりするための場所であり、百科事典の記事ではありません。ただし、公開の場ですので、許諾されていない文章の転載はご遠慮ください。

登録利用者は自分用の利用者サンドボックスを作成できます(サンドボックスを作成する、解説)。 その他のサンドボックス: 共用サンドボックス | モジュールサンドボックス 記事がある程度できあがったら、編集方針を確認して、新規ページを作成しましょう。 |

ヨーロッパの言語(ヨーロッパのげんご)の殆どはインド・ヨーロッパ語族に属す.この語族はいくつもの分枝に分かれ,そのなかにはロマンス諸語,ゲルマン語派,バルト語派,スラヴ語派,アルバニア語,ケルト語派,アルメニア語,ギリシア語がある.ウラル語族にはハンガリー語,フィンランド語,エストニア語が含まれ,これもヨーロッパに広く分布している.テュルク諸語とモンゴル諸語(いずれも語族と扱われることも多い)にもヨーロッパで用いられる言語があり,北コーカサス語族と南コーカサス語族は地理的な意味でのヨーロッパの南東端で重要である.ピレネー山脈の西側のバスク語はどのグループにも属さない孤立した言語であり,マルタ語はセム語派のなかでヨーロッパで公用語の地位を持つ唯一の言語である.

インド・ヨーロッパ語族

[編集]インド・ヨーロッパ語族の言語は,何千年も前に話されていたと考えられているインド・ヨーロッパ祖語から派生したものである.インド・ヨーロッパ語族の言語はヨーロッパ全体で話されているが,とくに西ヨーロッパで卓越している.

アルバニア語

[編集]アルバニア語には大きく分けてゲグ方言とトスク方言の2つの方言があり,アルバニアとコソボ,及びモンテネグロ,セルビア,トルコ,イタリア南部 (Arbëresh language) ,マケドニア西部,ギリシャ (Arvanitika) ,の一部で話されている.またさらに多くの国で,アルバニアからの移民がアルバニア語を話す.

アルメニア語

[編集]アルメニア語には西アルメニア語と東アルメニア語の2つの主要な方言がある.アルメニア語は,唯一の公用語としての地位を持っているアルメニアと近隣のグルジア,イラン,アゼルバイジャンで話されている.非常に少数ながらトルコにも話者がおり(西アルメニア語と Homshetsi 方言),あちこちに散らばる国外の小さなアルメニア人コミュニティ (Armenian diaspora) が話者として存在する国も数多い.

バルト語派

[編集]

バルト語派の言語はリトアニア(リトアニア語,サモギティア語)とラトビア(ラトビア語,ラトガリア語)で話されている.サモギティア語ラトガリア語はたいていそれぞれリトアニア語とラトビア語の方言として扱われる.

新クロニア語 (New Curonian) [要出典]は,現在リトアニアとロシアのカリーニングラード州に分割されているクルシュー砂州で話されていたが,今ではほとんど死語になっている.バルト語派には他にも死語となっているものがいくつもあり,プロシア語やスドヴィア語を挙げることができる.

ケルト語派

[編集]

大陸ケルト語は紀元後最初の1000年で死語となったが,以前はイベリアやガリアから小アジアまでにわたる地域で話されていた.近代のケルト語派の諸言語は次のように分類されている.

- ブリソン諸語.おもにウェールズで話されるウェールズ語や,ブルトン語(フランス北西部のブルターニュ半島),コーンウォール語(イングランド南西部のコーンウォール).

- ゲール諸語.アイルランド語(主にアイルランドで話される),スコットランド・ゲール語(スコットランド),マン島語(アイリッシュ海の島マン島).

ゲルマン語派

[編集]

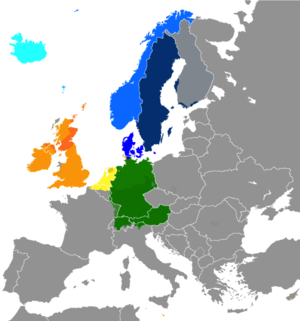

北ゲルマン語群 西ゲルマン語群 ドットで多言語が一般に用いられる地域を表した.

The Germanic languages make up the predominant language family in northwestern Europe, reaching from Iceland to Sweden and from parts of the United Kingdom and Ireland to Austria. There are two extant major sub-divisions: West Germanic and North Germanic. A third group, East Germanic, is now extinct; the only known surviving East Germanic texts are written in the Gothic language.

West Germanic

[編集]There are three major groupings of West Germanic languages: Anglo-Frisian, Low Franconian (now primarily modern Dutch) and High German.

Anglo-Frisian

[編集]The Anglo-Frisian language family has two major groups:

- The English languages descended from the Old English language of the Anglo-Saxons and include:

- English, the de facto language of United Kingdom, also used in English-speaking Europe

- Modern Scots, spoken in Scotland and Ulster.

- The Frisian languages are spoken by about 500,000 Frisians, who live on the southern coast of the North Sea in the Netherlands and Germany, and include West Frisian, Saterlandic, and North Frisian.

German

[編集]German is spoken throughout Germany, Austria, Liechtenstein, the East Cantons of Belgium and much of Switzerland (including the northeast areas bordering on Germany and Austria).

There are several groups of German dialects:

- High German include several dialect families:

- Standard German (High German)

- Central German dialects, spoken in central Germany and include Luxembourgish

- High Franconian, a family of transitional dialects between Central and Upper High German

- Upper German, including Austro-Bavarian and Swiss German

- Low German

Low Franconian

[編集]- Dutch is spoken throughout the Netherlands, northern Belgium, as well as the Nord-Pas de Calais region of France, and around Düsseldorf in Germany. In Belgian and French contexts, Dutch is sometimes referred to as Flemish. Dutch dialects are varied and cut across national borders. In Germany it is called East Bergish.

- Afrikaans is spoken by South African emigrant communities in Europe, most notably in the Netherlands, Belgium, and the United Kingdom.

North Germanic

[編集]The North Germanic languages are spoken in Scandinavian countries and include Danish (Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Norwegian (Norway), Swedish (Sweden and parts of Finland), Elfdalian or Övdalian (in a small part of central Sweden), Faroese (Faroe Islands), and Icelandic (Iceland).

Greek

[編集]- Greek is the official language of Greece and Cyprus, and there are Greek-speaking enclaves in Albania, Bulgaria, Italy, the Republic of Macedonia[要出典], Romania, Georgia, Ukraine, Lebanon, Egypt, Israel, Jordan and Turkey, and in Greek communities around the world. Dialects of modern Greek that originate from Attic Greek (through Koine and then Medieval Greek) are Cappadocian, Pontic, Cretan, Cypriot, Katharevousa, and Yevanic

- Griko is, debatably, a Doric dialect of Greek. It is spoken in the lower Calabria region and in the Salento region of Southern Italy.

- Tsakonian is a Doric dialect of the Greek language spoken in the lower Arcadia region of the Peloponnese around the village of Leonidio

Indo-Iranian languages

[編集]The Indo-Iranian languages have two major groupings, Indo-Aryan languages including Romani, and Iranian languages, which include Kurdish, Persian, and Ossetian.

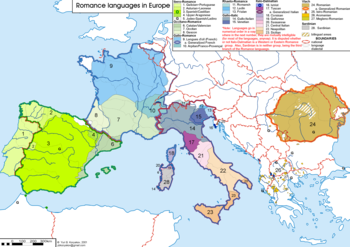

Romance languages

[編集]

The Romance languages descended from the Vulgar Latin spoken across most of the lands of the Roman Empire. Some of the Romance languages are official in the European Union and the Latin Union and the more prominent ones are studied in many educational institutions worldwide. Three of the Romance languages (Spanish, French, and Portuguese) are spoken by one billion speakers worldwide. Many other Romance languages and their local varieties are spoken throughout Europe, and some are recognized as regional languages.

The list below is a summary of Romance languages commonly encountered in Europe:

- Aragonese is recognized, but not official, in Aragon (Spain).

- Asturian is recognized, but not official, in the Spanish region of Asturias.

- Catalan is official in Andorra; co‑official in the Spanish regions of Catalonia, Valencian Community (as Valencian) and Balearic Islands; and recognized, but not official, in La Franja of Aragon. It is also natively spoken in Northern Catalonia, France, in the Languedoc-Roussillon region (Llengadoc-Rosselló) and in the city of Alghero, Sardinia, Italy (as Alguerese).

- Corsican is spoken on the French island of Corsica and is much more closely related to the Italian or Central Italian regional languages (its origins are in Pisan dialect, it is spoken in the northern coast of Sardinia as well, and it transitions smoothly to Tuscan Italian through the islands between Corsica and the peninsula. Its prospects of survival are better than most French minority languages but it still suffers from the lack of promotion.

- Franco-Provençal, sometimes called "Arpitan", protected by statutes in the Aosta Valley Autonomous Region of Italy, also spoken alpine valleys of the province of Turin, two communities in province of Foggia, Romandy region of western Switzerland, and in east central France (i.e., between standard French and Occitan domains). It is in serious danger of extinction.

- French is official in France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Monaco, Switzerland and the Channel Islands. It is also official in Canada, in many African countries and in overseas departments and territories of France.

- Galician, akin to Portuguese, is co‑official in Galicia, Spain. It is also spoken by Galician diaspora.

- Italian is official in Italy, San Marino, Switzerland, Vatican City, and Istria (in Croatia and Slovenia)

- Latin is usually classified as an Italic language of which the Romance languages are a subgroup. It is extinct as a spoken language, but it is widely used as a liturgical language by the Roman Catholic Church and studied in many educational institutions. It is also the official language of the Holy See. Latin was the main language of literature, sciences, and arts for many centuries and greatly influenced all European languages.

- Leonese is recognized in Spain's autonomous Castile and León region

- Ligurian is a Gallo-Romance language spoken in Liguria in Northern Italy, Monaco and in the villages of Carloforte and Calasetta in Sardinia. It belongs to the Northern Italian group of Romance languages, albeit with some peculiar characteristics.

- Mirandese is officially recognized by the Portuguese Parliament.

- Norman has been debatedly referred to as a language in its own right or a dialect of standard French with its own regional character. Its use is recognized in the Channel Islands, remnants of the historical Duchy of Normandy, and since 2008 it is among the regional languages recognised in the French constitution.

- Occitan is spoken principally in France, but is only officially recognized in Spain as one of the three official languages of Catalonia (termed there Aranese), and in Italy as a minority language. Its use was severely reduced due to the once de jure and currently de facto promotion of French.

- Picard is spoken in two regions in the far north of France – Nord-Pas-de-Calais and Picardy – and in parts of the Belgian region of Wallonia. Belgium's French Community gave full official recognition to Picard as a regional language.

- Piedmontese, Western Lombard and Emiliano-Romagnolo form a mutually intelligible dialect continuum in Northern Italy, sometimes known as Northern Italian.

- Portuguese is official in Portugal. It is also official in several former Portuguese colonies in Africa, Eastern Asia as well as in America (see Geographic distribution of Portuguese and Community of Portuguese Language Countries).

- Romanian is official in Romania, Moldova (as Moldovan), and Vojvodina (Serbia).

- Romansh is an official language of Switzerland.

- Sardinian is co-official in the Sardinia Autonomous Region, of Italy. It is also spoken by Sardinian diaspora. It is considered the most conservative of the Romance languages in terms of phonology.

- Sicilian is spoken primarily in Sicily, Italy. With its dialects, spoken in Southern Calabria and Southern-east Apulia, it is also referred to as the "extreme-southern Italian language group"

- Spanish (also termed "Castilian") is official in Spain. It is also official in most Latin American countries with the exception of Brazil, French Guyana and Haiti.

Slavic

[編集]Slavic languages are spoken in large areas of Central Europe, Southern Europe and Eastern Europe including Russia.

- East Slavic languages include Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Rusyn, and Pannonian-Rusyn.

- West Slavic languages include Czech, Kashubian, Polish, Slovak, and Sorbian. Some dialects of Polish, such as Silesian, were recognised as separate languages.[1]

- South Slavic languages include Bosnian, Bulgarian, Croatian, Macedonian, Montenegrin, Old Church Slavonic (a liturgical language), Romano-Serbian (a mixed language), Serbian, and Slovene.

Languages not from the Indo-European family

[編集]Basque

[編集]The Basque language (or Euskara) is a language isolate and the ancestral language of the Basque people who inhabit the Basque Country, a region in the western Pyrenees mountains mostly in northeastern Spain and partly in southwestern France of about 3 million inhabitants, where it is spoken fluently by about 750,000 and understood by more than 1.5 million people.

Basque is directly related to ancient Aquitanian, and it is likely that an early form of the Basque language was present in Western Europe before the arrival of the Indo-European languages in the area. The language may have been spoken since Paleolithic times.

Basque is also spoken by immigrants in Australia, Costa Rica, Mexico, the Philippines and the United States, especially in the states of Nevada, Idaho, and California.[2]

Kartvelian languages

[編集]

The Kartvelian language group consists of Georgian and the related languages of Svan, Mingrelian, and Laz. Proto-Kartvelian is believed to be a common ancestor language of all Kartvelian languages, with the earliest split occurring in the second millennium BC or earlier when Svan was separated. Megrelian and Laz split from Georgian roughly a thousand years later, roughly at the beginning of the first millennium BC (e.g., Klimov, T. Gamkrelidze, G. Machavariani).

The group is considered as isolated, and although for simplicity it is at times grouped with North Caucasian languages, no linguistic relationship exists between the two language groups.

North Caucasian

[編集]North Caucasian languages (sometimes called simply "Caucasic", as opposed to Kartvelian, and to avoid confusion with the concept of the "Caucasian race") is a blanket term for two language families spoken chiefly in the north Caucasus and Turkey—the Northwest Caucasian family (including Abkhaz, spoken in Abkhazia, and Circassian) and the Northeast Caucasian family, spoken mainly in the border area of the southern Russian Federation (including Dagestan, Chechnya, and Ingushetia).

Many linguists, notably Sergei Starostin and Sergei Nikolayev, believe that the two groups sprang from a common ancestor about 5,000 years ago.[3] However this view is difficult to evaluate, and remains controversial.

Uralic

[編集]

Europe has a number of Uralic languages and language families, including Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian.

Turkic

[編集]

- Oghuz languages in Europe include Turkish which is spoken mainly in Turkey, Balkans, Cyprus and amongst Turkish minority in Western and Central Europe, along with Azeri in Azerbaijan and Gagauz in Gagauzia.

- Kypchak languages are also found in Europe, namely Crimean Tatar, Karaim, Krymchak which can be found in parts of Ukraine (Crimea), Lithuania, and Poland. Kypchak languages such as Tatar and Kumyk language are also present in European parts of Russian Federation.

- Oghur languages were historically spoken over the eastern parts of continent, however most of them are extinct today, with exception of Chuvash.

Mongolic

[編集]The Mongolic languages originated in Asia, and most did not proliferate west to Europe. Kalmyk is spoken in the Republic of Kalmykia, part of the Russian Federation, and is thus the only native Mongolic language spoken in Europe.

Semitic

[編集]Cypriot Maronite Arabic

[編集]Cypriot Maronite Arabic (also known as Cypriot Arabic) is a variety of Arabic spoken by Maronites in Cyprus. Most speakers live in Nicosia, but others are in the communities of Kormakiti and Lemesos. Brought to the island by Maronites fleeing Lebanon over 700 years ago, this variety of Arabic has been influenced by Greek in both phonology and vocabulary, while retaining certain unusually archaic features in other respects.

Hebrew

[編集]Hebrew has been written and spoken by the Jewish communities of all of Europe in liturgical, educational, and often conversational contexts since the entry of the Jews into Europe some time during the late antiquity. Its restoration as the official language of Israel has accelerated its secular use. It also has been used in educational and liturgical contexts by some segments of the Christian population. Hebrew has its own consonantal alphabet, in which the vowels may be marked by diacritical marks termed pointing in English and Niqqud in Hebrew. The Hebrew alphabet was also used to write Yiddish, a West Germanic language, and Ladino, a Romance language, formerly spoken by Jews in northern and southern Europe respectively, but now nearly extinct in Europe itself.

Maltese

[編集]Maltese is a Semitic language with Romance and Germanic influences, spoken in Malta.[4][5][6][7] It is based on Sicilian Arabic, with influences from Italian (particularly Sicilian), French, and, more recently, English.

It is unique in that it is the only Semitic language whose standard form is written in the Latin alphabet. It is also the smallest official language of the EU in terms of speakers, and the only official Semitic language within the EU.

General issues

[編集]Linguae Francae—past and present

[編集]Europe has had a number of languages that were considered linguae francae over some ranges for some periods according to some historians. Typically in the rise of a national language the new language becomes a lingua franca to peoples in the range of the future nation until the consolidation and unification phases. If the nation becomes internationally influential, its language may become a lingua franca among nations that speak their own national languages. Europe has had no lingua franca ranging over its entire territory spoken by all or most of its populations during any historical period. Some linguae francae of past and present over some of its regions for some of its populations are:

- Classical Greek and then Koine Greek in the Mediterranean Basin from the Athenian empire to the eastern Roman Empire, being replaced by Modern Greek.

- Koine Greek and Modern Greek, in the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire and other parts of the Balkans south of the Jireček Line.[8]

- Vulgar Latin and Late Latin among the uneducated and educated populations respectively of the Roman empire and the states that followed it in the same range no later than 900 AD; medieval Latin and Renaissance Latin among the educated populations of western, northern, central and part of eastern Europe until the rise of the national languages in that range, beginning with the first language academy in Italy in 1582/83; new Latin written only in scholarly and scientific contexts by a small minority of the educated population at scattered locations over all of Europe; ecclesiastical Latin, in spoken and written contexts of liturgy and church administration only, over the range of the Roman Catholic Church.

- Lingua Franca or Sabir, the original of the name, a Romance-based pidgin language of mixed origins used by maritime commercial interests around the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages and early Modern Age.[9]

- Spanish as Castilian in Spain and New Spain from the times of the Catholic Monarchs and Columbus, c. 1492; that is, after the Reconquista, until established as a national language in the times of Louis XIV, ca. 1648; subsequently multinational in all nations in or formerly in the Spanish Empire.[10]

- Old French in continental western European countries and in the Crusader states.[11]

- French from the golden age under Cardinal Richelieu and Louis XIV c. 1648; i.e., after the Thirty Years' War, in France and the French colonial empire, until established as the national language during the French Revolution of 1789 and subsequently multinational in all nations in or formerly in the various French Empires.[11]

- English in Great Britain until its consolidation as a national language in the Renaissance and the rise of Modern English; subsequently internationally under the various states in or formerly in the British Empire; globally since the victories of the predominantly English speaking countries (United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and others) and their allies in the two world wars ending in 1918 (World War I) and 1945 (World War II) and the subsequent rise of the United States as a superpower and major cultural influence.

- Middle Low German (14th–16th century, during the heyday of the Hanseatic League).

- German in Northern, Central, and Eastern Europe.[12]

- Czech, mainly during the reign of Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV but also during other periods of Bohemian control over the Holy Roman Empire.

- Polish, due to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

- Russian in Eastern Europe and Central Asia from the World War II to the break‑up of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact.

First dictionaries and grammars

[編集]The earliest dictionaries were glossaries, i.e., more or less structured lists of lexical pairs (in alphabetical order or according to conceptual fields). The Latin-German (Latin-Bavarian) Abrogans was among the first. A new wave of lexicography can be seen from the late 15th century onwards (after the introduction of the printing press, with the growing interest in standardizing languages).

Language and identity, standardization processes

[編集]In the Middle Ages the two most important defining elements of Europe were Christianitas and Latinitas. Thus language—at least the supranational language—played an elementary role[要説明]. The concept of the nation state became increasingly important. Nations adopted particular dialects as their national language. This, together with improved communications, led to official efforts to standardise the national language, and a number of language academies were established (e.g., 1582 Accademia della Crusca in Florence, 1617 Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft in Weimar, 1635 Académie française in Paris, 1713 Real Academia Española in Madrid). Language became increasingly linked to nation as opposed to culture, and was also used to promote religious and ethnic identity (e.g., different Bible translations in the same language for Catholics and Protestants).

The first languages for which standardisation was promoted included Italian (questione della lingua: Modern Tuscan/Florentine vs. Old Tuscan/Florentine vs. Venetian > Modern Florentine + archaic Tuscan + Upper Italian), French (the standard is based on Parisian), English (the standard is based on the London dialect) and (High) German (based on the dialects of the chancellery of Meissen in Saxony, Middle German, and the chancellery of Prague in Bohemia ("Common German")). But several other nations also began to develop a standard variety in the 16th century.

Scripts

[編集]

この節の加筆が望まれています。 |

The main scripts used in Europe today are the Latin and Cyrillic, but with Greek having its own script. All of the aforementioned are alphabets.

History

[編集]The Greek alphabet was derived from the Phoenician and Latin was derived from the Greek via the Old Italic alphabet.

In the Early Middle Ages, Ogham was used in Ireland and runes (derived the Old Italic script) in Scandinavia. Both were replaced in general use by the Latin alphabet by the Late Middle Ages. The Cyrillic script was derived from the Greek with the first texts appearing around 940 AD.

Around 1900 there were two variants of the Latin alphabet used in Europe: Antiqua and Fraktur. Fraktur was used most for German, Estonian, Latvian, Norwegian and Danish whereas Antiqua was used for Italian, Spanish, French, Portuguese, English, Romanian, Swedish and Finnish. The Fraktur variant was banned by Hitler in 1941, having been described as "Schwabacher Jewish letters".[13] Other scripts have historically been in use in Europe, including Arabic during the era of the Ottoman Empire, Phoenician, from which modern Latin letters descend, Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs on Egyptian artefacts traded during Antiquity, and various runic systems used in Northern Europe preceding Christianisation.

Language and the Council of Europe

[編集]The most ancient historical social structure of Europe is that of politically independent tribes, each with its own ethnic identity, based among other cultural factors on its language. For example, the Latini speaking Latin in Latium. A Linguistic conflict has been important in European history. Historical attitudes towards linguistic diversity are illustrated by two French laws: the Ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts (1539), which said that every document in France should be written in French (i.e., neither in Latin nor in Occitan) and the Loi Toubon (1994), which aimed to eliminate Anglicisms from official documents. States and populations within a state have often resorted to war to settle their differences. Attempts have been made to prevent such hostilities: one such initiative was the Council of Europe, founded in 1949, whose membership is affirms the right of minority language speakers to use their language fully and freely.[14] The Council of Europe is committed to protecting linguistic diversity. Currently all European countries except France, Andorra and Turkey have signed the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, while Greece, Iceland and Luxembourg have signed it, but have not ratified it. This framework entered into force in 1998.

Language and the European Union

[編集]Official status

[編集]The European Union designates one or more languages as "official and working" with regard to any member state if they are the official languages of that state. The decision as to whether they are and their use by the EU as such is entirely up to the laws and policies of the member states. In the case of multiple official languages the member state must designate which one is to be the working language.[15]

As the EU is an entirely voluntary association established by treaty — a member state may withdraw at any time — each member retains its sovereignty in deciding what use to make of its own languages; it must agree to legislate any EU acceptance criteria before membership. The EU designation as official and working is only an agreement concerning the languages to be used in transacting official business between the member state and the EU, especially in the translation of documents passed between the EU and the member state. The EU does not attempt in any way to govern language use in a member state.

Currently the EU has designated by agreement with the member states 23 languages as "official and working:" Bulgarian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Irish, Italian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Maltese, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish and Swedish.[15] This designation provides member states with two "entitlements:" the member state may communicate with the EU in the designated one of those languages and view "EU regulations and other legislative documents" in that language.[16]

Proficiency

[編集]The European Union and the Council of Europe have been collaborating in a number of tasks, among which is the education of member populations in languages for "the promotion of plurilingualism" among EU member states,[17] The joint document, "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR)", is an educational standard defining "the competencies necessary for communication" and related knowledge for the benefit of educators in setting up educational programs. That document defines three general levels of knowledge: A Basic User, B Independent User and C Proficient User.[18] The ability to speak the language falls under competencies B and C ranging from "can keep going comprehensibly" to "can express him/herself at length with a natural, effortless, unhesitating flow."[19]

These distinctions were simplified in a 2005 independent survey requested by the EU's Directorate-General for Education and Culture regarding the extent to which major European languages were spoken in member states. The results were published in a 2006 document, "Europeans and Their Languages", or "Eurobarometer 243", which is disavowed as official by the European Commission, but does supply some scientific data concerning language use in the EU. In this study, statistically relevant samples of the population in each country were asked to fill out a survey form concerning the languages that they spoke with sufficient competency "to be able to have a conversation".[20] Some of the results showing the distribution of major languages are shown in the maps below. The darkest colors report the highest proportion of speakers. Only EU members were studied. Thus data on Russian speakers were gathered, but Russia is not an EU member and so Russian does not appear in Russia on the maps. It does appear as spoken to the greatest extent in the Baltic countries, which are EU members that were formerly under Soviet rule; followed by former Eastern bloc countries such as Poland, the Czech Republic, and the eastern portions of Germany (former socialist East Germany).

Notes

[編集]- ^ http://www.omniglot.com/writing/silesian.php

- ^ “Basque”. UCLA Language Materials Project, UCLA International Institute. 2 November 2009閲覧。

- ^ Nikolayev, S., and S. Starostin. 1994 North Caucasian Etymological Dictionary. Moscow: Asterisk Press. Available online.

- ^ Marie Alexander and others (2009年). “2nd International Conference of Maltese Linguistics: Saturday, September 19 – Monday, September 21, 2009”. International Association of Maltese Linguistics. 2 November 2009閲覧。

- ^ Aquilina, J. (1958). “Maltese as a Mixed Language”. Journal of Semitic Studies 3 (1): 58–79. doi:10.1093/jss/3.1.58.

- ^ Aquilina, Joseph (July–September, 1960). “The Structure of Maltese”. Journal of the American Oriental Society 80 (3): 267–68.

- ^ Werner, Louis; Calleja, Alan (November/December 2004). “Europe's New Arabic Connection”. Saudi Aramco World.

- ^ Counelis, James Steve (March 1976). “Review [untitled] of Ariadna Camariano-Cioran, Les Academies Princieres de Bucarest et de Jassy et leur Professeurs”. Church History 45 (1): 115–116. "...Greek, the lingua franca of commerce and religion, provided a cultural unity to the Balkans...Greek penetrated Moldavian and Wallachian territories as early as the fourteenth century.... The heavy influence of Greek culture upon the intellectual and academic life of Bucharest and Jassy was longer termed than historians once believed."

- ^ Wansbrough, John E. (1996). “Chapter 3: Lingua Franca”. Lingua Franca in the Mediterranean. Routledge

- ^ Jones, Branwen Gruffydd (2006). Decolonizing international relations. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 98

- ^ a b Calvet, Louis Jean (1998). Language wars and linguistic politics. Oxford [England]; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 175–76

- ^ Darquennes, Jeroen; Nelde, Peter (2006). “German as a Lingua Franca”. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 26: 61–77.

- ^ Facsimile of Bormann's Memorandum (in German)

The memorandum itself is typed in Antiqua, but the [[:en:NSDAP|]] [[:en:letterhead|]] is printed in Fraktur.

"For general attention, on behalf of the Führer, I make the following announcement:

It is wrong to regard or to describe the so‑called Gothic script as a German script. In reality, the so‑called Gothic script consists of Schwabach Jew letters. Just as they later took control of the newspapers, upon the introduction of printing the Jews residing in Germany took control of the printing presses and thus in Germany the Schwabach Jew letters were forcefully introduced.

Today the Führer, talking with Herr Reichsleiter Amann and Herr Book Publisher Adolf Müller, has decided that in the future the Antiqua script is to be described as normal script. All printed materials are to be gradually converted to this normal script. As soon as is feasible in terms of textbooks, only the normal script will be taught in village and state schools.

The use of the Schwabach Jew letters by officials will in future cease; appointment certifications for functionaries, street signs, and so forth will in future be produced only in normal script.

On behalf of the Führer, Herr Reichsleiter Amann will in future convert those newspapers and periodicals that already have foreign distribution, or whose foreign distribution is desired, to normal script". - ^ “European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages: Strasbourg, 5.XI.1992”. Council of Europe (1992年). Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ a b “Regulation No. 1 determining the languages to be used by the European Economic Community” (pdf). European Commission, European Union (2009年). 5 November 2009閲覧。

- ^ “Languages of Europe: Official EU languages”. European Commission, European Union (2009年). 5 November 2009閲覧。

- ^ “Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR)”. Council of Europe. 5 November 2009閲覧。

- ^ Page 23.

- ^ Page 29.

- ^ “Europeans and Their Languages” (pdf). European Commission. p. 8 (2006年). November 5, 2009閲覧。

See also

[編集]- Demography of Europe

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- Eurolinguistics

- Languages of the European Union

- List of endangered languages in Europe

- List of extinct languages of Europe

- Multilingual countries and regions of Europe

- Travellingua

External links

[編集]- Everson, Michael (2001年). “The Alphabets of Europe” (English). evertype.com. 19 March 2010閲覧。

- Reissmann, Stefan (2006年). “Luingoi in Europa” (Esperanto, English, German). Reissmann & Argador. 2 November 2009閲覧。

- Zikin, Mutur (2005–06). “Europako Mapa linguistikoa” (Basque and others). muturzikin.com. 2 November 2009閲覧。

- Haarmann, Harald (2011年). “Europe's Mosaic of Languages” (English and others). Institute of European History. 2 November 2, 2011閲覧。