利用者:おいしい豚肉/sandbox/病のクー・フーリン

『クー・フーリンの衰弱とエウェルのたった一度の嫉妬』(アイルランド語: Serglige Con Culainn agus Óenét Emire)はアルスター物語群に分類される作者不詳のアイルランドの説話であり、10-11世紀の物と見られる。単に『クー・フーリンの衰弱』、あるいは『エウェルのたった一度の嫉妬』とも。 現存する写本の中では『赤牛の書』とダブリン大学トリニティカレッジ写本1363の二冊に所収されている。

表題の「エウェル」とはクー・フーリンの妻の名であるが、作中では彼女は「エトネ」と「エウェル」という二つの名で呼ばれる。この例に代表される『クー・フーリンの衰弱』内の一貫性の欠如は、この説話が元々は異なる二つの説話を継ぎ合わせて作られた事が原因であると考えられている。

物語のあらすじは以下の通りである。妖精ファンとリー・バンの姉妹が変化した鳥を狩ろうとしたクー・フーリンは突然昏倒し、幻視の中で彼女らから鞭打たれる。これが原因でおよそ一年もの間寝たきりになってしまった彼は、病の快癒と引き換えに異界の戦争に参加してリー・バンの夫に助勢する。この恩賞としてクー・フーリンはファンと同衾を許される。異界から帰還した後もクー・フーリンはファンとの関係を続けたが、これが彼の妻に知れる事になった。

Literary and historical value

[編集]In the assessment of Myles Dillon,

- The story of Cú Chulainn's visit to the Other World has a special claim on our attention, because of its long descriptions of the Irish Elysium, here called Mag Mell 'the Plain of Delights', and also for the quality of the poetry which makes up almost half of the text. In some of the poems one recognizes the tension and grace which were later so finely cultivated in the bardic schools, and the moods of sorrow and joy are shared by the reader; the content is not sacrificed for the form ... The scene between Cú Chulainn and his wife after he has given the magic birds to the other women (§6) and the humorous account of Lóeg's conversation with Lí Ban (§14) are instances of the sudden intimacy in these Irish stories...[1]

Origins and manuscripts

[編集]『病のクー・フーリン』は二冊の写本に所収されており、 The story survives in two manuscripts, the twelfth-century Book of the Dun Cow and a seventeenth-century copy of this manuscript, Trinity College, Dublin, H. 4. 22.[2]

しかし、『褐牛の書』に所収されて現存する『病のクー・フーリン』は、明らかに二つの異なる版を継ぎ合わされた物である。 本来所収されていたのは『褐牛の書』の主要写字生の手によるものであった(ディロンはこの版を校訂本Aと呼んだ)が、 後に別の写字生の手によって、一部が消され上書きされた(→パリンプセスト)か、あるいはフォリオが外され差し替えられたかして、変更が加えられている。 この変更部分は恐らくは現在では遺失した写本『Slaneの黄書』(アイルランド語: Lebor Buide Sláni)からの筆写であると考えられる(ディロンはこの『Slaneの黄書』所収の版を校訂本Bと呼んだ)。 また、この写字生は単に他の写本から筆写したのみではなく、自身の創作を付け加えた可能性もある。

Precisely how much of our surviving text belongs to each source has been the subject of debate.

The material judged to derive from Recension B exhibits linguistic features pointing, amongst later ones, to the ninth century, while the language of A seems to be eleventh-century.[3]

A has long been considered the more conservative version of the story nevertheless, but John Carey has argued that B is the earlier version.[4]

異なる版が組み合わされたことが原因で、この物語は一貫性に欠け矛盾を残している。顕著な例がクー・フーリンの妻の名であり、彼女は最初は Ethne Ingubai と呼ばれていたが物語が進むとエウェルという名に置き換えられる。

登場人物

[編集]- クー・フーリン

- アルスター1の英雄。

- クー・フーリンの妻

- エトネ、あるいはエウェルの名で呼ばれる。

- ファン

- 妖精の女。マナナン・マクリルの妻。クー・フーリンと関係を持つ。

- リー・バン

- 妖精の女。ファンの姉妹でありラヴリド・ルアト=ラーウ=アル=フラデヴの妻。その名は「女の鑑」を意味する。

ストーリー

[編集]アルスターの英雄クー・フーリンは男たちと共にムルテウネの水辺で鳥を狩っていた。男たちの多くは自身の妻のために二匹の鳥を狩っていたが、これは彼女らのガウンの肩飾りに鳥の羽を使用することが目的であった。 クーフーリンの妻エウェル以外の全ての女性に鳥が行き渡ると、彼は妻のために最も大きくそして最も美しい鳥を狩ることを決めた。

The only birds still in the sky are indeed the largest and most exotic-looking,しかし二羽の海鳥は黄金の鎖によってお互いの足を繋がれ、眠りを誘う魔法の歌を歌っていた。 エウェルはこの様子から二羽の鳥が異界から来たものであることを悟り、クーフーリンに鳥を殺さないよう告げた。 He attempts to do so anyway, but only manages to strike one of the birds on the feathers of her wing, damaging her wing, but not inflicting a mortal wound. クー・フーリンは病に倒れ、立石の横で熱にうなされながら意識を失い横たわった[5]。

In his fevered state he sees two women approaching. They are Fand and Lí Ban, whom he assaulted while they were in bird form. 彼女らが馬鞭を手にクー・フーリンを打ち据えた結果、彼は息も絶え絶えになり、その後 Lí Ban が彼を再訪するまでのおよそ1年もの間、病で寝たきりで過ごすことになった。

Lí Banは彼に異界「喜びの野」を訪れ、この地の戦いで Fand の敵を倒し彼女を助けるよう依頼した。 この助力に対する交換条件として、Lí Banは彼の病を癒すことを約束した。 クーフーリン本人はこの提案を拒絶したのだが、彼の戦車御者であるライグがagrees to go.

ここで突然話の流れが途切れ、新しくタラ王に選ばれた彼の里子赤い縞のルギド(メイヴの甥であり、彼女の兄弟姉妹による近親相姦から生まれた)に対してクーフーリンが長い助言を行う場面が挿入される。 この箇所は tecosca (教え)とよばれるアイルランドの文学ジャンルに属すものであり、ディロンは『説話の原型に含まれていたとはとても考えられない』と推測している[6]。 一方で、クーフーリンがこの助言の場で見せる彼らしからぬ賢明さは、魔法による病気がもたらした有益な副作用であったとも解釈可能であろう[7]。

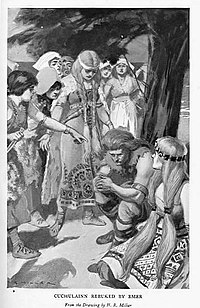

On his return, Láeg, with the help of Emer (who berates her husband for choosing his pride over his health) manages to convince Cú Chulainn to accompany him to Fand's lands.[5]

「喜びの野」でクー・フーリンは Fand と Lí Ban に加勢して彼女らの敵を討ち果たす。 Fand は同意のうえでクー・フーリンと同衾したが、この様子はナイフで武装した女性たちの一団を伴ったエウェルに発見され、彼女は Fand と対峙する。 長い討論の末、二人はお互いのクーフーリンへの愛情が利己的な物ではないことを認め、双方がクーフーリンに対し、相手と共に過ごすよう要求するようになった。結局、 Fand が、自身には夫マナナン・マク・リルがいるが、クー・フーリンを失えばエウェルが一人きりになってしまうことを理由に、エウェルこそがクー・フーリンと共に過ごすべきであると決めた。とは言え、この失恋は Fand とクーフーリンを大いに苦しめることになった。 Fand は夫マナナンに頼んで彼の所有物である霧の外套を彼女とクーフーリンの間で振らせた。これは二人が二度と会う事がないよう保証するものであった。ドルイドはクーフーリンとエウェルに忘れ薬を与え、この薬によって夫婦は一連の出来事をすっかり忘れてしまった[5]。

この物語は、一般的には写本の改変を行った写字生によるものとされる供述によって幕を閉じる。 「これが妖精によってクーフーリンが見せられた破滅的な幻視である。 The text closes with a statement generally attributed to scribe who altered the manuscript text (sometimes omitted from translations), that 'that is the disastrous vision shown to Cú Chulainn by the fairies. For the diabolical power was great before the faith, and it was so great that devils used to fight with men in bodily form, and used to show delights and mysteries to them, as though they really existed. So they were believed to be; and ignorant men used to call those visions síde and áes síde'.[8]

近・現代への影響

[編集]Augusta, Lady Gregory included a Victorian version of the story in her 1902 collection Cuchulain of Muirthemne. Gregory's version was loosely adapted by William Butler Yeats for his 1922 play The Only Jealousy of Emer.

音楽においても、アーノルド・バックスの交響詩『ファンドの庭』や、ザ・ポーグスの『ザ・シック・ベッド・オブ・クーフーリン』 (日本語題:『回想のロンドン』)がこの説話を題材としている。

Bibliography

[編集]Manuscripts

[編集]- Lebor na hUidre (LU) fol. 43a-50b (+H) (RIA)

- H 4.22, fol. X, p. 89-104 (TCD)

Editions

[編集]- Dillon, Myles (ed.). "The Trinity College text of Serglige Con Culainn." Scottish Gaelic Studies 6 (1949): 139-175; 7 (1953): 88 (=corrigenda). Based on H 4.22, with readings from Lebor na hUidre.

- Dillon, Myles (ed.). Serglige Con Culainn. Mediaeval and Modern Irish Series 14. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1953. Based on LU. Available from CELT

- Smith, Roland Mitchell (ed. and tr.). "On the Bríatharthecosc Conculain." Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 15 (1924): 187-98. Based on part of the text, Cúchulainn's instruction.

- Windisch, Ernst (ed.). Irische Texte mit Wörterbuch. Leipzig, 1880. 197-234. Based on LU, with variants from H 4.22.

Translations

[編集]- Dillon, Myles (tr.). "The Wasting Sickness of Cú Chulainn." Scottish Gaelic Studies 7 (1953): 47-88. Based on H 4.22.

- Gantz, Jeffrey (tr.). Early Irish Myths and Sagas. London, 1981. 155-78. Based on LU, but omitting the interpolation of Chuchulainn's tescoc.

- Leahy, A. H., *The Sick-Bed of Cúchulainn, 1905

- Smith, Roland Mitchell (ed. and tr.). "On the Bríatharthecosc Conculain." Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 15 (1924): 187-98. Based on part of the text, Cúchulainn's instruction.

References

[編集]- ^ Dillon, Myles (ed.). Serglige Con Culainn. Mediaeval and Modern Irish Series 14. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1953. p. ix. Available from CELT.

- ^ Dillon, Myles (ed.). Serglige Con Culainn. Mediaeval and Modern Irish Series 14. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1953. p. xi. Available from CELT.

- ^ Myles Dillon, ‘On the Text of Serglige Con Culainn’, Éigse, 3 (1941–2), 120–9; (ed.), Serglige Con Culainn, Mediaeval and Modern Irish Series, 14 ([Dublin]: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1953), xi–xvi; Trond Kruke Salberg, ‘The Question of the Main Interpolation of H into M’s Part of the Serglige Con Culainn in the Book of the Dun Cow and Some Related Problems’, Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie, 45 (1992), 161–81, esp. 161–2.

- ^ John Carey, ‘The Uses of Tradition in Serglige Con Culainn’, in Ulidia: Proceedings of the First International Conference on the Ulster Cycle of Tales, Belfast and Emain Macha, 8–12 April 1994, ed. J. P. Mallory and Gerard Stockman (Belfast: December, 1994), pp. 77–84, at 81–3; Joanne Findon, A Woman’s Words: Emer and Female Speech in the Ulster Cycle (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 145–46.

- ^ a b c 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグです。「MacKillop1」という名前の注釈に対するテキストが指定されていません - ^ Dillon, Myles (ed.). Serglige Con Culainn. Mediaeval and Modern Irish Series 14. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1953. p. x. Available from CELT.

- ^ 。John Carey, ‘The Uses of Tradition in Serglige Con Culainn’, in Ulidia: Proceedings of the First International Conference on the Ulster Cycle of Tales, Belfast and Emain Macha, 8–12 April 1994, ed. J. P. Mallory and Gerard Stockman (Belfast: December, 1994), pp. 77–84; John T. Koch, 'Serglige Con Culainn', in Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ed. by John T. Koch (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2005), pp. 1607-8.

- ^ Alaric Hall, Elves in Anglo-Saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity, Anglo-Saxon Studies, 8 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2007; pbk repr. 2009), p. 143.