利用者:デザート/ロンドン自然史博物館の天井

ロンドン自然史博物館のヒンツェ・ホール(英: Hintze Hall)[注釈 1]とノース・ホール(英: North Hall)にある一対の装飾天井は、1881年の開館時に披露された。双方、設計は博物館を担当した建築家アルフレッド・ウォーターハウスによってなされ、装飾は画家チャールズ・ジェームズ・リーによってなされた。

ヒンツェ・ホールの天井は162枚の板絵で構成されている。うち108枚は博物館の歴史ないしイギリス帝国、また博物館の訪問者にとって重要な植物が描かれており、残りは様式化された装飾的な植物画となっている。小さなノース・ホールの天井は36枚の板絵で構成され、そのうちの18枚にはブリテン諸島に生育する植物が描かれている。これらは天井の漆喰に直接描かれ、視覚効果を高めるために金箔も使われている。

自然史コレクションは当初、母体である大英博物館と建物を共有していたが、帝国の拡大に伴い、自然史に対する一般人や経済界の関心が著しく高まり、博物館の自然史コレクションに加えられる標本の数も増加した。 1860年、クジラなどの大型標本を展示できる大きな建物に、独立した自然史博物館を設立することが合意された。

ウォーターハウスが最初ロマネスク様式の館を設計したとき、初代工務大臣アクトン・スミー・エイトンは費用面から天井の装飾を許可しなかった。しかし、ウォーターハウスは博物館建設時の足場がある間に絵画を施してしまえば追加費用は掛からず、その上緊迫で飾れば天井がより魅力的になるとしてエイトンを説き伏せた。

ヒンツェ・ホールの天井は、屋根の頂点の両側に3枚ずつ、計6列の板絵で構成されている。 建物の南端にある踊り場の上では、天井は9つの区画に分かれている。 各区の最上部3枚は、ウォーターハウスが「古風」と呼んだ板絵から成り、緑色の背景に様式化された植物が描かれている。 各区の下の6つの板絵には、イギリス帝国にとって特に重要な植物が淡い背景で描かれている。 ヒンツェ・ホールの残りの部分には、古風な板絵が同じ様式で残されているが、下部の6枚の板絵にはそれぞれ1つの植物が描かれており、6枚の板絵にまたがって、同じ淡い背景で描かれている。 小さなノース・ホールの天井は、わずか4列の板絵で構成されている。 一番上の2列は、当時イギリスを構成していた国々の紋章を単純化してあしらったもので、下の2列は、イギリスまたはアイルランドで発見された異なる植物を描いている。

天井は廉価で、非常に壊れやすく、定期的な修理が必要である。 1924年、1975年、2016年に大規模な保存修復工事が行われた。 2016年の修復は、以前ヒンツェ・ホールにあったディプロドクスの骨格標本の鋳型「ディッピー」の撤去と、天井から吊り下げられたシロナガスクジラの骨格標本の設置と同時に行われた。

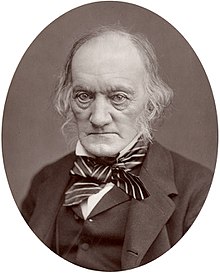

自然史部門の責任者であったリチャード・オーウェンは、「インデックス・コレクション」(博物館の代表的な収蔵品)を展示するヒンツェ・ホールへ入り、放射状に広がる展示室を閲覧、最後にノース・ホールでブリテン諸島の自然史を見学するという動線を想定していた。

背景

[編集]

Irish physician Hans Sloane was born in 1660, and since childhood had a fascination with natural history.[1] In 1687 Sloane was appointed personal doctor to Christopher Monck, the newly appointed Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica,[1] and lived on that island until Monck died in October 1688.[2] During his free time in Jamaica Sloane indulged his passion for biology and botany, and on his return to London brought with him a collection of plants, animal and mineral specimens and numerous drawings and notes regarding the local wildlife, which eventually became the basis for his major work A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica (1707–1725).[2] He became one of England's leading doctors, credited with the invention of chocolate milk and with the popularisation of quinine as a medicine,[A] and in 1727 King George II appointed him Physician in Ordinary (doctor to the Royal Household).[4]

アイルランドの医者ハンス・スローンは幼少を自然史に魅了されて過ごした。1687年、スローンはジャマイカ副総督に任命されたばかりのクリストファー・モンクの専属医に任命され、モンクが1688年10月に歿するまでジャマイカで過ごした。

Building on the collection he had brought from Jamaica, Sloane continued to collect throughout his life, using his new-found wealth to buy items from other collectors and to buy out the collections of existing museums.[5][B] During Sloane's life there were few public museums in England, and by 1710 Sloane's collection filled 11 large rooms, which he allowed the public to visit.[7] Following his death on 11 January 1753, Sloane stipulated that his collection—by this time filling two large houses[8]—was to be kept together for the public benefit if at all possible.[7] The collection was initially offered to King George II, who was reluctant to meet the £20,000 (about £3,800,000 in 2025 terms[9]) purchase cost stipulated in Sloane's will.[10][C] Parliament ultimately agreed to establish a national lottery to fund the purchase of Sloane's collection and the Harleian Library which was also currently for sale, and to unite them with the Cotton library, which had been bequeathed to the nation in 1702, to create a national collection.[11] On 7 June 1753 the British Museum Act 1753 was passed, authorising the unification of the three collections as the British Museum and establishing the national lottery to fund the purchase of the collections and to provide funds for their maintenance.[12]

The trustees settled on Montagu House in Bloomsbury as a home for the new British Museum, opening it to the public for the first time on 15 January 1759.[13][D] With the British Museum now established numerous other collectors began to donate and bequeath items to the museum's collections,[16] which were further swelled by large quantities of exhibits brought to England in 1771 by the first voyage of James Cook,[17] by a large collection of Egyptian antiquities (including the Rosetta Stone) ceded by the French in the Capitulation of Alexandria,[18] by the 1816 purchase of the Elgin Marbles by the British government who in turn passed them to the museum,[18] and by the 1820 bequest of the vast botanical collections of Joseph Banks.[17][E] Other collectors continued to sell, donate or bequeath their collections to the museum, and by 1807 it was clear that Montagu House was unable to accommodate the museum's holdings. In 1808–09, in an effort to save space, the newly appointed keeper of the natural history department George Shaw felt obliged to destroy large numbers of the museum's specimens in a series of bonfires in the museum's gardens.[18] The 1821 bequest of the library of 60,000 books assembled by George III forced the trustees to address the issue, as the bequest was on condition that the collection be displayed in a single room, and Montagu House had no such room available.[21] In 1823 Robert Smirke was hired to design a replacement building, the first parts of which opened in 1827 and which was completed in the 1840s.[22]

Plans for a Natural History building

[編集]

With more space for displays and able to accommodate large numbers of visitors, the new British Museum proved a success with the public, and the natural history department proved particularly popular.[23] Although the museum's management had traditionally been dominated by classicists and antiquarians,[24] in 1856 the natural history department was split into separate departments of botany, zoology, mineralogy and geology, each with their own keeper and with botanist and palaeontologist Richard Owen as superintendent of the four departments.[25] By this time the expansion of the British Empire had led to an increased appreciation of the importance of natural history on the part of the authorities, as territorial expansion had given British companies access to unfamiliar species, the commercial possibilities of which needed to be investigated.[26][F]

By the time of Owen's appointment, the collections of the natural history departments had increased tenfold in size in the preceding 20 years, and the museum was again suffering from a chronic lack of space.[27] There had also long been criticism that because of the varied nature of its displays the museum was confusing and lacked coherence; as early as 1824 Sir Robert Peel, the Home Secretary, had commented that "what with marbles, statues, butterflies, manuscripts, books and pictures, I think the museum is a farrago that distracts attention".[28] Owen proposed that the museum be split into separate buildings, with one building to house the works of Man (art, antiquities, books and manuscripts) and one to house the works of God (the natural history departments);[29] he argued that the expansion of the British Empire had led to an increased ability to procure specimens, and that increased space to store and display these specimens would both aid scholarship, and enhance Britain's prestige.[30]

The great instrument of zoological science, as Lord Bacon points out, is a Museum of Natural History. Every civilized state in Europe possesses such a Museum. That of England has been progressively developed to the extent which the restrictive circumstances under which it originated have allowed. The public is now fully aware, by the reports that have been published by Parliament, by representations to Government, and by articles in Reviews and other Periodicals, of the present condition of the National Museum of Natural History and of its most pressing requirements. Of them the most pressing, and the one essential to rendering the collections worthy of this great empire, is 'space'. Our colonies include parts of the earth where the forms of plants and animals are the most strange. No empire in the world had ever so wide a range for the collection of the various forms of animal life as Great Britain. Never was there so much energy and intelligence displayed in the capture and transmission of exotic animals by the enterprising traveller in unknown lands and by the hardy settler in remote colonies, as by those who start from their native shores of Britain. Foreign Naturalists consequently visit England anticipating to find in her capital and in her National Museum the richest and most varied materials for their comparisons and deductions. And they ought to be in a state pre-eminently conducive to the advancement of a philosophical zoology, and on a scale commensurate with the greatness of the nation and the peculiar national facilities for such perfection. But, in order to receive and to display zoological specimens, space must be had, and not merely space for display, but for orderly display: the galleries should bear relation in size and form with the nature of the classes respectively occupying them. They should be such as to enable the student or intelligent visitor to discern the extent of the class, and to trace the kind and order of the variations which have been superinduced upon its common or fundamental characters.—Richard Owen, President's Address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, 1858[31]

In 1858 a group of 120 leading scientists wrote to Benjamin Disraeli, at the time the Chancellor of the Exchequer, complaining about the inadequacy of the existing building for displaying and storing the natural history collections.[28][G] In January 1860, the trustees of the museum approved Owen's proposal.[21] (Only nine of the British Museum's fifty trustees supported Owen's scheme, but 33 trustees failed to turn up to the meeting. As a consequence, Owen's plan passed by nine votes to eight.[29]) Owen envisaged a huge new building of 500,000平方フィート (46,000 m2) for the natural history collections, capable of exhibiting the largest specimens.[32] Owen felt that exhibiting large animals would attract visitors to the new museum; in particular, he hoped to collect and display whole specimens of large whales while he still had the opportunity, as he felt that the larger species of whale were on the verge of extinction.[32] (It was reported that when the Royal Commission on Scientific Instruction asked Owen how much space would be needed, he replied "I shall want space for seventy whales, to begin with".[33]) In October 1861 Owen gave William Ewart Gladstone, the newly appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer, a tour of the cramped natural history departments of the British Museum, to demonstrate how overcrowded and poorly lit the museum's galleries and storerooms were, and to impress on him the need for a much larger building.[34]

After much debate over a potential site, in 1864 the site formerly occupied by the 1862 International Exhibition in South Kensington was chosen. Francis Fowke, who had designed the buildings for the International Exhibition, was commissioned to build Owen's museum.[35] In December 1865 Fowke died, and the Office of Works commissioned little-known architect Alfred Waterhouse, who had never previously worked on a building of this scale,[36] to complete Fowke's design. Dissatisfied with Fowke's scheme, in 1868 Waterhouse submitted his own revised design, which was endorsed by the trustees.[35][H]

Owen, who considered animals more important than plants, was unhappy with the museum containing botanical specimens at all, and during the negotiations that led to the new building supported transferring the botanical collections to the new Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew to amalgamate the national collections of living and preserved plants.[38] However, he decided that it would diminish the significance of his new museum were it not to cover the whole of nature,[39] and when the Royal Commission on Scientific Instruction was convened in 1870 to review the national policy on scientific education Owen successfully lobbied for the museum to retain its botanical collections.[40] In 1873 construction finally began on the new museum building.[34]

Waterhouse's building

[編集]

Waterhouse's design was a Romanesque scheme,[42] loosely based on German religious architecture;[43] Owen was a leading creationist, and felt that the museum served a religious purpose in displaying the works of God.[44] The design was centred around a very large rectangular Hintze Hall and a smaller hall to the north.[45] Visitors would enter from the street into the Hintze Hall,[46] which would hold what Owen termed an "index collection" of typical specimens, intended to serve as an introduction to the museum's collections for those unfamiliar with natural history.[36][47][48] Extended galleries were to radiate to the east and west from this Hintze Hall to form the south face of the museum, with further galleries to the east, west and north to be added when funds allowed to complete a rectangular shape.[49][I]

Uniquely for the time, Waterhouse's building was faced inside and out with terracotta, the first building in England to be so designed;[52] although expensive to build, this was resistant to the acid rain of heavily polluted London, allowed the building to be washed clean,[J] and also allowed it to be decorated with intricate mouldings and sculptures.[55] A smaller North Hall, immediately north of the Hintze Hall, would be used for exhibits specifically relating to British natural history.[56][K] On 18 April 1881 the new British Museum (Natural History) opened to the public.[58][59] As relocating exhibits from Bloomsbury was a difficult and time-consuming process, much of the building remained empty at the time the museum opened.[56]

Hintze Hall

[編集]

As well as being large, the Hintze Hall was to be very high, rising the full 72-フート (22 m) height of the building to a plaster-lined mansard roof,[60][61] with skylights running the length of the hall at the junction between the roof and the wall.[60] A grand staircase at the northern end of the hall, flanked by archways leading to the smaller North Hall,[56] led to balconies running almost the full length of the hall to a staircase which in turn led to a large landing above the main entrance, such that a visitor entering the hall would walk the full length of the floor of the hall to reach the first staircase, and then the full length of the balcony to reach the second.[62] As a consequence, it posed a difficulty to Waterhouse's plans to decorate the building. As the skylights were lower than the ceiling the roof was in relative darkness compared to the rest of the room,[46] and owing to the routes to be taken by visitors, the design needed to be attractive when viewed both from the floor below, and from the raised balconies to the each side.[62] To address this, Waterhouse decided to decorate the 170-フート (52 m)[61] ceiling with painted botanical panels.[60]

The lower panels will have representations of foliage treated conventionally. The upper panels will be treated with more variety of colour and the designs will be of an archaic character. The chief idea to be represented is that of growth. The colours will be arranged so that the most brilliant will be near the apex of the roof.—Alfred Waterhouse, June 1876[60]

Acton Smee Ayrton, the First Commissioner of Works, was hostile to the museum project, and sought to cut costs wherever possible;[63] he disliked art, and felt that it was his responsibility to restrain the excesses of artists and architects.[50] Having already insisted that Waterhouse's original design for wooden ceilings and a lead roof be replaced with cheaper plaster and slate,[50][64] Ayrton vetoed Waterhouse's plan to decorate the ceiling.[64] Waterhouse eventually persuaded Ayrton that provided the ceiling were decorated while the scaffolding from its construction remained in place, a decorated ceiling would be no more expensive than a plain white one. He prepared two sample paintings of the pomegranate and magnolia for Ayrton, who approved £1435 (about £160,000 in 2025 terms[9]) to decorate the ceiling.[64] Having obtained approval for the paintings, Waterhouse managed to convince Ayrton that the paintings' appeal would be enhanced if certain elements were gilded.[64]

Records do not survive of how the plants to be represented were chosen and who created the initial designs.[60] Knapp & Press (2005) believe that it was almost certainly Waterhouse himself, likely working from specimens in the museum's botanical collections,[60] while William T. Stearn, writing in 1980, believes that the illustrations were chosen by botanist William Carruthers, who at the time was the museum's Keeper of Botany.[65] To create the painted panels from the initial cartoons, Waterhouse commissioned Manchester artist Charles James Lea of Best & Lea, with whom he had already worked on Pilmore Hall in Hurworth-on-Tees.[63] Waterhouse provided Lea with a selection of botanical drawings, and requested that Lea "select and prepare drawings of fruits and flowers most suitable and gild same in the upper panels of the roof";[63] it is not recorded who drew the cartoons for the paintings, or how the species were chosen.[66] Best & Lea agreed a fee of £1975 (about £220,000 in 2025 terms[9]) for the work.[67] How the panels were painted is not recorded, but it is likely Lea painted directly onto the ceiling from the scaffolding.[66][67]

Main ceiling

[編集]

Waterhouse and Lea's design for the ceiling is based on a theme of growth and power. From the skylights on each side, three rows of panels run the length of the main hall, with the third, uppermost rows on each side meeting at the apex of the roof.[68] The two lower rows are divided into blocks of six panels apiece, each block depicting a different plant species.[69] Plants spread their branches upwards towards the apex, representing the theme of growth.[68] The supporting girders of the ceiling are spaced at every third column of panels, dividing the panels into square blocks of nine;[70] the girders are an integral part of the design, designed to be barely visible from the ground but highly visible from the upper galleries, representing industry working with nature.[71]

The girders themselves are based on 12th-century German architecture. Each comprises a round arch, braced with repeating triangles to create a zig-zag pattern. Within each upward-facing triangle is a highly stylised gilded leaf; the six different leaf designs repeat across the length of the hall.[71] Running perpendicular to the girders—i.e., along the length of the hall—are seven iron support beams. The topmost of these forms the apex of the roof, and the next beam down on each side, separating the topmost from the middle row of panels, is painted with a geometric design of cream and green rectangles.[72] The next beam down on each side, separating the middle from the lowest row of panels, is decorated in the same shades of cream and green, but this time with a design of green triangles pointing upwards.[72] The lowest of the beams, separating the panels from the skylights, is painted deep burgundy and is labelled with the scientific name of the plant depicted in the panels above; the names are flanked with a motif of gilt dots and highly stylised roses.[72] At Owen's request, the plants were labelled with their binomial names rather than their English names, as he felt this would serve an educational purpose to visitors.[73]

Other than on the outermost edges of the panels at the two ends of the hall,[74] each set of nine panels is flanked alongside the girders by an almost abstract design of leaves; these decorations continue along the space between the skylights and the girders to reach the terracotta walls below, providing a visible connection between the walls and the ceiling designs.[73]

Between the main entrance and the landing of the main staircase,[75] the lower two rows of panels all have a pale cream background, intended to draw the viewer's attention to the plant being illustrated; each plant chosen was considered significant either to visitors, or to the museum itself.[73] Each block of three columns depicts a different species, but all have a broadly similar design.[73] The central column in the lowest row depicts the trunk or stalk of the plant in question, while the panels on either side and the three panels of the row above depict the branches of the plant spreading from the lower central panel.[73] The design was intended to draw the viewer's eye upwards, and to give the impression that the plants are growing.[76]

Archaic panels

[編集]Above the six-panel sets and adjacent to the apex of the roof lie the top rows of panels. These panels, called the "archaic" panels by Waterhouse, are of a radically different design to those below. Each panel is surrounded by gilded strips and set against a dark green background, rather than the pale cream of the six-panel sets; the archaic panels also continue beyond the six panel sets and over the landing of the main staircase, to run the full length of the Hintze Hall.[75]

The archaic panels depict flattened, stylised plants in pale colours with gilt highlighting, sometimes accompanied by birds, butterflies and insects.[77][78] Unlike the six-panel sets the archaic panels are not labelled, and while some plants on the archaic panels are recognisable others are stylised beyond recognition.[78][79]

No records survive of how Waterhouse and Lea selected the designs for the archaic panels,[80] or on from which images they were derived.[74] Owing to the flattened nature of the designs, it is possible that they were based on pressed flowers in the museum's herbarium, or on illustrations in the British Museum's collection of books on botany.[80] Some of the archaic panels appear to be simplified versions of the illustrations in Nathaniel Wallich's book Plantae Asiaticae Rariores.[81]

Footnotes

[編集]- ^ Sloane's chocolate milk was intended for medicinal use, in particular as a believed cure for tuberculosis and fainting fits.[3][4]

- ^ Sloane's motivation for collecting is unknown. Towards his death he claimed that by studying as much of the world as possible he hoped to have a closer understanding of the will of God, but there is little evidence that he was particularly pious during most of the period in which he assembled his collections.[6]

- ^ Hans Sloane's will was specific as to how the collection was to be disposed of. He named a committee of 63 trustees, a mixture of scientists, politicians, religious figures, other collectors, business leaders and Sloane family members. The trustees were instructed to offer the collection for £20,000 to the King; if the King declined to purchase it they were to offer it to the Royal Society, Oxford University and the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, and if they declined it was to be offered to an assortment of foreign academic bodies. Only if none of the named institutions were willing to purchase the collection were the trustees to allow it to be broken up.[7]

- ^ Although the collections were open to the public, the early British Museum was not easy to visit. Prospective visitors had to apply in writing to the porter and return the next day to find out whether they had been judged 'fit and proper persons', only after which would they be issued a ticket to attend at a specified time in future.[14] Visitors were not permitted to spend more than an hour in each of the three departments of Natural and Artificial Productions, Printed Books, and Manuscripts.[15]

- ^ Joseph Banks had accompanied Captain James Cook on his voyage to Australia. Banks persuaded Cook to call his landing site Botany Bay, on account of the wide variety of specimens he collected there; Cook had intended to call the site Stingray Bay.[19] Banks went on to become one of the founders of Kew Gardens.[20]

- ^ A similar approach to natural history had already been undertaken by Spain during its colonial expansion in the Americas; from 1712 onwards Spanish government and religious officials were obliged to record and report on any plants, animals or minerals they encountered with potential commercial uses.[26]

- ^ Owen was not a signatory to the letter, probably because he was an employee of the museum and was reluctant to criticise his employer in public. It is likely that he orchestrated its writing.[28]

- ^ The delay between the selection of the site in 1864 and the acceptance of Waterhouse's design in 1868 was the result of repeated changes of government; the United Kingdom had five different prime ministers during this period, each of whom had a different opinion on the controversial scheme to build a major museum in what was then a distant and relatively inaccessible suburb.[37]

- ^ A lack of funds meant that Waterhouse's planned east, west and north galleries were never built, and the central halls and south front were the only parts of his design to be completed.[50] Between 1911 and 1913 plans were drawn up to build extensions to the east and west in a similar style to Waterhouse's, but the First World War meant the plans were abandoned.[51] By the time funds became available for further expansion in the late 20th century, Waterhouse's style was out of fashion, and later additions to the museum are in a radically different architectural style.[49]

- ^ Waterhouse chose terracotta because it was washable, but for much of the museum's history the exterior was never cleaned, giving the building a reputation for ugliness. It was only in 1975 that the exterior was fully washed, restoring it to Waterhouse and Owen's intended appearance.[53][54]

- ^ The use of the smaller North Hall for the exhibition of British natural history was controversial. Henry Woodward, the Keeper of the geological department, felt that this would be the topic of the most interest to visitors, and that as a consequence it should be in the more prominent Central Hall.[57]

References

[編集]- ^ a b Thackray & Press 2001, p. 11.

- ^ a b Thackray & Press 2001, p. 13.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 43.

- ^ a b Thackray & Press 2001, p. 14.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 15.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Thackray & Press 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 11.

- ^ a b c イギリスのインフレ率の出典はClark, Gregory (2024). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth (英語). 2024年5月31日閲覧。

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 27.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 28.

- ^ a b Thackray & Press 2001, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Thackray & Press 2001, p. 31.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 45.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 47.

- ^ a b Thackray & Press 2001, p. 41.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 42.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 52.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 54.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 65.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Girouard 1981, p. 8.

- ^ a b Thackray & Press 2001, p. 60.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 63.

- ^ Owen, Richard (1858年). “President's Address to the BAAS, 1858”. 16 December 2018閲覧。

- ^ a b Thackray & Press 2001, p. 61.

- ^ "This is a great day with the young people of the metropolis". Opinion and Editorial. The Times (英語). No. 30171. London. 18 April 1881. col D, p. 9.

- ^ a b Girouard 1981, p. 7.

- ^ a b Thackray & Press 2001, p. 66.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 15.

- ^ Girouard 1981, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 124.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 125.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 126.

- ^ Girouard 1981, p. 40.

- ^ Girouard 1981, p. 31.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 16.

- ^ Girouard 1981, p. 27.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 17.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Girouard 1981, p. 12.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 62.

- ^ a b Thackray & Press 2001, p. 68.

- ^ a b c Girouard 1981, p. 22.

- ^ Girouard 1981, p. 64.

- ^ Girouard 1981, p. 53.

- ^ Girouard 1981, p. 57.

- ^ Stearn 1980, p. 53.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Knapp & Press 2005, p. 99.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 100.

- ^ Girouard 1981, p. 23.

- ^ Thackray & Press 2001, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f Knapp & Press 2005, p. 19.

- ^ a b Stearn 1980, p. 47.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 66.

- ^ a b c Knapp & Press 2005, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Knapp & Press 2005, p. 21.

- ^ Stearn 1980, p. 52.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 123.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 23.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Girouard 1981, p. 38.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 28.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Knapp & Press 2005, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e Knapp & Press 2005, p. 31.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 129.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 48.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 58.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 51.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 122.

- ^ a b Knapp & Press 2005, p. 52.

- ^ Knapp & Press 2005, p. 54.

Bibliography

[編集]- Cowen, D. V. (1984). Flowering Trees and Shrubs in India, Sixth Edition. Bombay: Thacker and Co. OCLC 803751318

- Draelos, Zoe Diana (2015). Cosmetic Dermatology: Products and Procedures. Chichester, UK: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-65546-7

- Girouard, Mark (1981). Alfred Waterhouse and the Natural History Museum (1999 ed.). London: Natural History Museum. ISBN 978-0-565-09135-4

- Knapp, Sandra; Press, Bob (2005). The Gilded Canopy. London: Natural History Museum. ISBN 978-0-565-09198-9

- Ponting, Clive (2000). World History: A New Perspective. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-6834-X

- Stearn, William T. (1980). The Natural History Museum at South Kensington. London: Natural History Museum. ISBN 978-0-565-09030-2

- Thackray, John; Press, Bob (2001). Nature's Treasurehouse: A History of the Natural History Museum (2013 ed.). London: Natural History Museum. ISBN 978-0-565-09318-1

External links

[編集]- Interactive and zoomable ultra-high-definition images of the Hintze Hall ceiling at the Google Cultural Institute

座標: 北緯51度29分46秒 西経00度10分35秒 / 北緯51.49611度 西経0.17639度

引用エラー: 「注釈」という名前のグループの <ref> タグがありますが、対応する <references group="注釈"/> タグが見つかりません