利用者:D.h/芸術/芸術(美術)の記事

この記事について

- Translation from en:Art 2007-06-15T14:03:23. By 170.252.177.xxx, Taw, 194.109.232.xxx, Larry_Sanger, Conversion script, et al.

Art is a (product of) human activity, made with the intention of stimulating the human senses as well as the human en:mind and/or en:spirit; thus art is an action, an object, or a collection of actions and objects created with the intention of transmitting emotions and/or ideas. Beyond this description, there is no general agreed-upon definition of art, since defining the boundaries of "art" is subjective, but the impetus for art is often called human en:creativity.

An artwork is normally assessed in quality by the amount of stimulation it brings about. The impact it has on people, the number of people that can relate to it, the degree of their appreciation, and the effect or influence it has or has had in the past, all accumulate to the "degree of art." Most artworks that are widely considered to be "masterpieces" possess these attributes.

Something is not generally considered "art" when it stimulates only the senses, or only the mind, or when it has a different primary purpose than doing so. However, some contemporary art challenges this idea.

As such, something can be deemed art in totality, or as an element of some object. For example, a painting may be a pure art, while a chair, though designed to be sat in, may include artistic elements. Art that has less functional value or intention may be referred to as en:fine art, while objects of artistic merit which serve a functional purpose may be referred to as en:craft. Paradoxically, an object may be characterized by the intentions (or lack thereof) of its creator, regardless of its apparent purpose; a cup (which ostensibly can be used as a container) may be considered art if intended solely as an ornament, while a painting may be deemed craft if mass-produced.

In the 1800s, art was primarily concerned with ideas of "Truth" and "Beauty." There was a radical break in the thinking about art in the early 1900s with the arrival of en:Modernism, and then in the late 1900s with the advent of en:Postmodernism. en:Clement Greenberg's 1960 article "Modernist Painting" defined Modern Art as "the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself."[1]

Greenberg originally applied this idea to the Abstract Expressionist movement and used it as a way to understand and justify flat (non-illusionistic) abstract painting. "Realistic, naturalistic art had dissembled the medium, using art to conceal art; Modernism used art to call attention to art. The limitations that constitute the medium of painting — the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment — were treated by the Old Masters as negative factors that could be acknowledged only implicitly or indirectly. Under Modernism these same limitations came to be regarded as positive factors, and were acknowledged openly."[1]

Though only originally intended as a way of understanding a specific set of artists, this definition of Modern Art underlies most of the ideas of art within the various art movements of the twentieth century and early twenty-first century. The art of en:Marcel Duchamp becomes clear when seen within this context; when submitting a urinal, titled fountain, to the Society of Independent Artists exhibit in 1917 he was critiquing the art exhibition using its own methods.

en:Andy Warhol became an important artist through critiquing popular culture, as well as the art world, through the language of that popular culture. The later en:postmodern artists of the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s took these ideas further by expanding this technique of self-criticism beyond "high art" to all cultural image-making, including fashion images, comics, billboards and pornography.

Usage

[編集]

The most common usage of the word "art," which rose to prominence after 1750, is understood to denote en:skill used to produce an aesthetic result.[2] Britannica Online defines it as "the use of skill and imagination in the creation of aesthetic objects, environments, or experiences that can be shared with others."[3] By any of these definitions of the word, artistic works have existed for almost as long as en:humankind: from early en:pre-historic art to en:contemporary art.

Many books and journal articles have been written about "art".[4] In 1998, en:Walt Weaver claimed that "It is self-evident that nothing concerning art is self-evident anymore."[5]

The first and broadest sense of "art" is the one that has remained closest to the older Latin meaning, which roughly translates to "skill" or "craft," and also from an Indo-European root meaning "arrangement" or "to arrange." In this sense, art is whatever is described as having undergone a deliberate process of arrangement by an agent. A few examples where this meaning proves very broad include artifact, artificial, artifice, en:artillery, medical arts, and en:military arts. However, there are many other colloquial uses of the word, all with some relation to its en:etymology.

The second and more recent sense of the word "art" is an abbreviation for "creative art" or "en:fine art." Fine art means that a skill is being used to express the artist’s creativity, or to engage the audience’s aesthetic sensibilities, or to draw the audience towards consideration of the "finer" things. Often, if the skill is being used in a common or practical way, people will consider it a en:craft instead of art. Likewise, if the skill is being used in a commercial or industrial way, it will be considered en:Commercial art instead of art. On the other hand, crafts and design are sometimes considered en:applied art. Some art followers have argued that the difference between fine art and applied art has more to do with value judgments made about the art than any clear definitional difference.[6] However, even fine art often has goals beyond pure creativity and self-expression. The purpose of works of art may be to communicate ideas, such as in politically-, spiritually-, or philosophically-motivated art; to create a sense of en:beauty (see en:aesthetics); to explore the nature of perception; for pleasure; or to generate strong en:emotions. The purpose may also be seemingly nonexistent.

The ultimate derivation of "fine" in "fine art" comes from the en:philosophy of en:Aristotle, who proposed four causes or explanations of a thing. The en:Final Cause of a thing is the purpose for its existence, and the term "fine art" is derived from this notion. If the Final Cause of an artwork is simply the artwork itself, "art for art's sake," and not a means to another end, then that artwork could appropriately be called "fine." The closely related concept of beauty is classically defined as "that which when seen, pleases." Pleasure is the final cause of beauty and thus is not a means to another end, but an end in itself.

Art can describe several things: a study of creative skill, a process of using the creative skill, a product of the creative skill, or the audience’s experience with the creative skill. The creative arts (“art” as discipline) are a collection of disciplines ("arts") that produce "artworks" ("art" as objects) that are compelled by a personal drive (art as activity) and echo or reflect a message, mood, or symbolism for the viewer to interpret (art as experience). Artworks can be defined by purposeful, creative interpretations of limitless concepts or ideas in order to communicate something to another person. Artworks can be explicitly made for this purpose or interpreted based on images or objects.

Art is something that stimulates an individual's thoughts, emotions, beliefs, or ideas through the senses. It is also an expression of an idea and it can take many different forms and serve many different purposes.

Although the application of scientific theories to derive a new scientific theory involves skill and results in the "creation" of something new, this represents science only and is not categorized as art.

Theories of art

[編集]en:Clement Greenberg's 1960 article "Modernist Painting" defined Modern Art as "the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself."[1]

Greenberg originally applied this idea to the Abstract Expressionist movement and used it as a way to understand and justify flat (non-illusionistic) abstract painting. "Realistic, naturalistic art had dissembled the medium, using art to conceal art; Modernism used art to call attention to art. The limitations that constitute the medium of painting — the flat surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment — were treated by the Old Masters as negative factors that could be acknowledged only implicitly or indirectly. Under Modernism these same limitations came to be regarded as positive factors, and were acknowledged openly."[1]

Though only originally intended as a way of understanding a specific set of artists, this definition of Modern Art underlies most of the ideas of art of within the various art movements of the twentieth century and early twenty-first century. The art of en:Marcel Duchamp becomes clear when seen within this context; when submitting a urinal, titled Fountain, to the Society of Independent Artists exhibit in 1917 he was critiquing the art exhibition using its own methods.

Art and class

[編集]Art has been perceived as belonging to one social class and often excluding others. In this context, art is seen as an upper-class activity associated with wealth, the ability to purchase art, and the leisure required to pursue or enjoy it. For example, the palaces of Versailles or the Hermitage in en:St. Petersburg with their vast collections of art, amassed by the fabulously wealthy royalty of Europe exemplify this view. Collecting such art is the preserve of the rich, in one viewpoint.

Before the 13th century in en:Europe, artisans were often considered to belong to a lower en:caste, however during the en:Renaissance artists gained an association with high status. "Fine" and expensive goods have been popular markers of status in many cultures, and continue to be so today. At least one of the important functions of art in the 21st century is as a marker of wealth and social status.

Utility of art

[編集]One of the defining characteristics of fine art as opposed to applied art is the absence of any clear usefulness or utilitarian value. However, this requirement is sometimes criticized as being class prejudice against labor and utility. Opponents of the view that art cannot be useful, argue that all human activity has some utilitarian function, and the objects claimed to be "non-utilitarian" actually have the function of attempting to mystify and codify flawed social hierarchies. It is also sometimes argued that even seemingly non-useful art is not useless, but rather that its use is the effect it has on the psyche of the creator or viewer.

Art is also used by art therapists, psychotherapists and clinical psychologists as en:art therapy. Art can also be used as a tool of en:Personality Test. The end product is not the principal goal in this case, but rather a process of healing, through creative acts, is sought. The resultant piece of artwork may also offer insight into the troubles experienced by the subject and may suggest suitable approaches to be used in more conventional forms of psychiatric therapy.

Graffiti art and other types of en:street art are graphics and images that are spray-painted or en:stencilled on publicly viewable walls, buildings, buses, trains, and bridges, usually without permission. This type of art is part of various youth cultures, such as the US en:hip-hop culture. It is used to express political views and depict creative images.

In a social context, art can serve to boost the public's morale. Art is often utilized as a form of en:propaganda, and thus can be used to subtly influence popular conceptions or mood. In some cases, artworks are appropriated to be used in this manner, without the creator having initially intended the art to be used as propaganda.

From a more anthropological perspective, art is often a way of passing ideas and concepts on to later generations in a (somewhat) universal language. The interpretation of this language is very dependent upon the observer’s perspective and context, and it might be argued that the very subjectivity of art demonstrates its importance in providing an arena in which rival ideas might be exchanged and discussed, or to provide a social context in which disparate groups of people might congregate and mingle.

Classification disputes about art

[編集]It is common in the en:history of art for people to dispute whether a particular form or work, or particular piece of work counts as art or not. In fact for much of the past century the idea of art has been to simply challenge what art is. en:Philosophers of Art call these disputes “classificatory disputes about art.” For example, Ancient Greek philosophers debated about whether or not en:ethics should be considered the “art of living well.” Classificatory disputes in the 20th century included: en:cubist and en:impressionist paintings, en:Duchamp’s urinal, the en:movies, superlative imitations of en:banknotes, en:propaganda, and even a crucifix immersed in urine. en:Conceptual art often intentionally pushes the boundaries of what counts as art and a number of recent conceptual artists, such as en:Damien Hirst and en:Tracy Emin have produced works about which there are active disputes. en:Video games and en:role-playing games are both fields where some recent critics have asserted that they do count as art, and some have asserted that they do not.

Philosopher David Novitz has argued that disagreement about the definition of art are rarely the heart of the problem. Rather, “the passionate concerns and interests that humans vest in their social life” are “so much a part of all classificatory disputes about art” (Novitz, 1996). According to Novitz, classificatory disputes are more often disputes about our values and where we are trying to go with our society than they are about theory proper. For example, when the en:Daily Mail criticized Hirst's and Emin’s work by arguing "For 1,000 years art has been one of our great civilising forces. Today, pickled sheep and soiled beds threaten to make barbarians of us all" they are not advancing a definition or theory about art, but questioning the value of Hirst’s and Emin’s work.

Famous examples of controversial European art of the 19th century include en:Theodore Gericault's "Raft of the Medusa" (1820), construed by many as a blistering condemnation of the French government's gross negligence in the matter, en:Edouard Manet's "Le Déjeuner sur l'Herbe" (1863), considered scandalous not because of the nude woman, but because she is seated next to fully-dressed men, and en:John Singer Sargent's "Madame Pierre Gautreau (Madam X)", (1884) which caused a huge uproar over the reddish pink used to color the woman's ear lobe, considered far too suggestive and supposedly ruining the high-society model's reputation.

In the 20th century, examples of high-profile controversial art include en:Pablo Picasso's Guernica (1937), en:Leon Golub's Interrogation III (1958), shocking the American conscience with a nude, hooded detainee strapped to a chair, surrounded by several ever-so-normal looking "cop" interrogators, and en:Andres Serrano's en:Piss Christ (1989).

In 2001, en:Eric Fischl created Tumbling Woman as a memorial to those who jumped or fell to their death on en:9/11. Initially installed at en:Rockefeller Center in New York City, within a year the work was removed as too disturbing.[7]

Forms, genres, mediums, and styles

[編集]

The creative arts are often divided into more specific categories, such as en:decorative arts, en:plastic arts, en:performing arts, or en:literature. So for example en:painting is a form of plastic art, and en:poetry is a form of literature.

An art form is a specific form for artistic expression to take, it is a more specific term than art in general, but less specific than “genre.” Some examples include, but are by no means, limited to:

- en:painting

- en:drawing

- en:printmaking

- en:sculpture

- en:ceramics

- en:graphic design

- en:digital art

- en:mixed media

- en:music

- en:poetry

- en:game design

- en:architecture

- cinema

- en:theatre

- en:photography

- en:model making

- en:cartooning

- en:origami

- en:mosaic

- en:graffiti

- en:internet art

- en:wood carving

A genre is a set of conventions and styles for pursuing an art form. For instance, a painting may be a en:still life, an abstract, a en:portrait, or a landscape, and may also deal with historical or domestic subjects. The boundaries between form and genre can be quite fluid. So, for example, it is not clear whether song lyrics are best thought of as an art form distinct from poetry, or a genre within poetry. Is cinematography a genre of photography (perhaps “motion photography”) or is it a distinct form?

An artistic medium is the substance the artistic work is made out of. So for example stone and bronze are both mediums that sculpture uses sometimes. Multiple forms can share a medium (poetry and music, both use sound), or one form can use multiple media.

An artwork or artist’s style is a particular approach they take to their art. Sometimes style embodies a particular artistic philosophy or goal. We might describe en:Joy Division as Minimalist in style, in this sense, for example. Sometimes style is intimately linked with a particular historical period, or a particular artistic movement. So we might describe Dali’s paintings as en:Surrealist in style in this sense. Sometimes style is linked to a technique used, or an effect produced, so we might describe a Roy Lichtenstein painting as pointillist, because of its use of small dots, even though it is not aligned with the original proponents of Pointillism. Lichtenstein used Ben-Day dots, which were used to color comic strips: they are evenly-spaced and create flat areas of color; pointillism employs dots that are spaced in a way to create variation in color and depth.

Many terms used to describe art, especially recent art, are hard to categorize as forms, genres, or styles; or such categorizations are disputed. No one doubts there is such a thing as en:land art, but is it best thought of as a distinct form of art? Or, perhaps, as a genre of en:architecture? Or perhaps as a style within the genre of en:landscape architecture? Are comics an art form, medium, genre, style, or perhaps more than one of these?

Art history

[編集]

Art predates history; sculptures, en:cave paintings, rock paintings, and en:petroglyphs from the en:Upper Paleolithic starting roughly 40,000 years ago have been found, but the precise meaning of such art is often disputed because so little is known about the cultures that produced them. The oldest art objects in the world: a series of tiny, drilled snail shells about 100000yrs old, were discovered in a South African cave, see en:Art of South Africa.

The great traditions in art have a foundation in the art of one of the great ancient civilizations: en:Ancient Egypt, en:Mesopotamia, Persia, India, en:China, Greece, Rome or en:Arabia (ancient en:Yemen and en:Oman). Each of these centers of early civilization developed a unique and characteristic style in their art. Because of the size and duration these civilizations, more of their art works have survived and more of their influence has been transmitted to other cultures and later times. They have also provided the first records of how en:artists worked. For example, this period of Greek art saw a veneration of the human physical form and the development of equivalent skills to show musculature, poise, beauty and anatomically correct proportions

In Byzantine and en:Gothic art of the Western en:Middle Ages, art focused on the expression of Biblical and not material truths, and emphasized methods which would show the higher unseen glory of a heavenly world, such as the use of gold in paintings, or glass in mosaics or windows, which also presented figures in idealized, patterned (i.e. "flat" forms).

The western en:Renaissance saw a return to valuation of the material world, and the place of humans in it, and this paradigm shift is reflected in art forms, which show the corporeality of the human body, and the three dimensional reality of landscape.

In the east, en:Islamic art's rejection of en:iconography led to emphasis on geometric patterns, en:Islamic calligraphy, and architecture. Further east, religion dominated artistic styles and forms too. India and Tibet saw emphasis on painted en:sculptures and en:dance with religious painting borrowing many conventions from sculpture and tending to bright contrasting colors with emphasis on outlines. China saw many art forms flourish, jade carving, bronzework, pottery (including the stunning en:terracotta army of Emperor Qin), poetry, calligraphy, music, painting, drama, fiction, etc. Chinese styles vary greatly from era to era and are traditionally named after the ruling dynasty. So, for example, en:Tang Dynasty paintings are monochromatic and sparse, emphasizing idealized landscapes, but en:Ming Dynasty paintings are busy, colorful, and focus on telling stories via setting and composition. Japan names its styles after imperial dynasties too, and also saw much interplay between the styles of calligraphy and painting. en:Woodblock printing became important in Japan after the 17th century.

The western en:Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century saw artistic depictions of physical and rational certainties of the clockwork universe, as well as politically revolutionary visions of a post-monarchist world, such as Blake’s portrayal of Newton as a divine geometer, or David’s propagandistic paintings. This led to Romantic rejections of this in favor of pictures of the emotional side and individuality of humans, exemplified in the novels of en:Goethe. The late 19th century then saw a host of artistic movements, such as en:academic art, en:symbolism, en:impressionism and en:fauvism among others.

By the 20th century these pictures were falling apart, shattered not only by new discoveries of relativity by en:Einstein [8] and of unseen psychology by en:Freud,[9] but also by unprecedented technological development accelerated by the implosion of civilisation in two world wars. The history of twentieth century art is a narrative of endless possibilities and the search for new standards, each being torn down in succession by the next. Thus the parameters of Impressionism, Expressionism, Fauvism, [:en:[Cubism]], en:Dadaism, en:Surrealism, etc cannot be maintained very much beyond the time of their invention. Increasing global interaction during this time saw an equivalent influence of other cultures into Western art, such as en:Pablo Picasso being influenced by African sculpture. Japanese woodblock prints (which had themselves been influenced by Western Renaissance draftsmanship) had an immense influence on Impressionism and subsequent development. Then African sculptures were taken up by Picasso and to some extent by en:Matisse. Similarly, the west has had huge impacts on Eastern art in 19th and 20th century, with originally western ideas like en:Communism and en:Post-Modernism exerting powerful influence on artistic styles.

en:Modernism, the idealistic search for truth, gave way in the latter half of the 20th century to a realization of its unattainability. Relativity was accepted as an unavoidable truth, which led to the period of en:contemporary art and postmodern criticism, where cultures of the world and of history are seen as changing forms, which can be appreciated and drawn from only with irony. Furthermore the separation of cultures is increasingly blurred and some argue it is now more appropriate to think in terms of a global culture, rather than regional cultures.

Characteristics of art

[編集]この記事は世界的観点から説明されていない可能性があります。 |

Here are some characteristics that art may display:

- encourages an intuitive understanding rather than a rational understanding, as, for example, with an article in a scientific journal;

- was created with the intention of evoking such an understanding or an attempt at such an understanding in the audience;

- was created with no other purpose or function other than to be itself (a radical, "pure art" definition);

- is elusive, in that the work may communicate on many different levels of appreciation; For example, in the case of en:Gericault's en:Raft of the Medusa, special knowledge concerning the shipwreck that the painting depicts, is not a prerequisite to appreciating it, but allows the appreciation of Gericault's political intentions in the piece.

- may offer itself to many different interpretations, or, though it superficially depicts a mundane event or object, invites reflection upon elevated themes;

- demonstrates a high level of ability or fluency within a medium; this characteristic might be considered a point of contention, since many modern artists (most notably, conceptual artists) do not themselves create the works they conceive, or do not even create the work in a conventional, demonstrative sense (one might think of en:Tracey Emin's controversial My Bed);

- confers particularly appealing or aesthetically satisfying structures or forms upon an original set of unrelated, passive constituents.

Skill

[編集]

Art can connote a sense of trained ability or mastery of a en:medium. Art can also simply refer to the developed and efficient use of a en:language to convey meaning with immediacy and or depth.

Basically, art is an act of expressing our feelings, thoughts, and observations. There is an understanding that is reached with the material as a result of handling it, which facilitates one's thought processes.

A common view is that the epithet “art”, particular in its elevated sense, requires a certain level of creative expertise by the artist, whether this be a demonstration of technical ability or an originality in stylistic approach such as in the plays of en:Shakespeare, or a combination of these two. For example, a common contemporary criticism of some en:modern art occurs along the lines of objecting to the apparent lack of skill or ability required in the production of the artistic object. One might take en:Tracey Emin's en:My Bed, or Hirst's en:The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, as examples of pieces wherein the artist exercised little to no traditionally recognised set of skills, but may be said to have innovated by exercising skill in manipulating the en:mass media as a medium. In the first case, Emin simply slept (and engaged in other activities) in her bed before placing the result in a gallery. She has been insistent that there is a high degree of selection and arrangement in this work, which include objects such as underwear and bottles around the bed. The shocking mundanity of this arrangement has proved to be startling enough to lead others to begin to interpret the work as art. In the second case, Hirst came up with the conceptual design for the artwork. Although he physically participated in the creation of this piece, he has left the eventual creation of many other works to employed artisans. In this case the celebrity of Hirst is founded entirely on his ability to produce shocking concepts, the actual production is, as with most objects a matter of assembly. These approaches are exemplary of a particular kind of contemporary art known as en:conceptual art.

Judgments of value

[編集]

Somewhat in relation to the above, the word art is also used to apply judgments of value, as in such expressions like "that meal was a work of art" (the cook is an artist), or "the art of deception," (the highly attained level of skill of the deceiver is praised). It is this use of the word as a measure of high quality and high value that gives the term its flavor of subjectivity.

Making judgments of value requires a basis for criticism. At the simplest level, a way to determine whether the impact of the object on the senses meets the criteria to be considered art, is whether it is perceived to be attractive or repulsive. Though perception is always colored by experience, and is necessarily subjective, it is commonly taken that that which is not aesthetically satisfying in some fashion cannot be art. However, "good" art is not always or even regularly aesthetically appealing to a majority of viewers. In other words, an artist's prime motivation need not be the pursuit of the aesthetic. Also, art often depicts terrible images made for social, moral, or thought-provoking reasons. For example, en:Francisco Goya's painting depicting the Spanish shootings of en:3rd of May en:1808, is a graphic depiction of a firing squad executing several pleading civilians. Yet at the same time, the horrific imagery demonstrates Goya's keen artistic ability in composition and execution and his fitting social and political outrage. Thus, the debate continues as to what mode of aesthetic satisfaction, if any, is required to define 'art'.

The assumption of new values or the rebellion against accepted notions of what is aesthetically superior need not occur concurrently with a complete abandonment of the pursuit of that which is aesthetically appealing. Indeed, the reverse is often true, that in the revision of what is popularly conceived of as being aesthetically appealing, allows for a re-invigoration of aesthetic sensibility, and a new appreciation for the standards of art itself. Countless schools have proposed their own ways to define quality, yet they all seem to agree in at least one point: once their aesthetic choices are accepted, the value of the work of art is determined by its capacity to transcend the limits of its chosen medium in order to strike some universal chord, by the rarity of the skill of the artist, or in its accurate reflection in what is termed the en:zeitgeist.

Communicating emotion

[編集]Art appeals to many of the human emotions. It can arouse en:aesthetic or moral feelings, and can be understood as a way of communicating these feelings. en:Artists express something so that their audience is aroused to some extent, but they do not have to do so consciously. Art explores what is commonly termed as the human condition that is essentially what it is to be human. Effective art often brings about some new insight concerning the human condition either singly or en-mass, which is not necessarily always positive, or necessarily widens the boundaries of collective human ability. The degree of skill that the artist has, will affect their ability to trigger an emotional response and thereby provide new insights, the ability to manipulate them at will shows exemplary skill and determination.

Creative impulse

[編集]From one perspective, art is a generic term for any product of the en:creative impulse, out of which sprang all other human pursuits, such as en:science via en:alchemy. The term "art" offers no true definition besides those based within the cultural, historical, and geographical context in which it is applied. It is because of the desire to create in the face of financial hardship, lack of recognition, or political opposition, that artists are sometimes thought of as misguided, or eccentric. However, the romantic myth of the starving artist in "his" en:garret is a very rare occurrence.

Symbols

[編集]Much of the development of individual artist deals with finding principles for how to express certain ideas through various kinds of en:symbolism. For example, en:Wassily Kandinsky developed his use of en:color in en:painting through a system of stimulus response, where over time he gained an understanding of the en:emotions that can be evoked by color and combinations of color.

Cultural traditions of art

[編集]

Several genres of art are grouped by cultural relevance, examples can be found in terms such as:

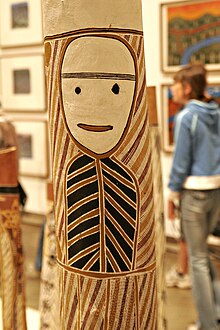

- en:Aboriginal art

- en:African art

- en:American craft

- Asian art as found in:

- en:Islamic art

- en:Maya art

- en:Latin American art

- Papua New Guinea

- en:Socialist Realism

- en:Visual arts of the United States

- en:Western art

See also

[編集]Lists

[編集]Related topics

[編集]- en:Arts

- en:Art gallery

- en:Abstract art

- en:Aesthetics, a philosophical field related to art

- en:Anthropology of art

- en:Applied art

- en:Art criticism

- en:Art groups

- en:Art history

- en:Art sale

- en:Art school

- en:Art styles, periods and movements

- en:Art techniques and materials

- en:Art therapy

- en:Artificial art (automatization of art production)

- en:Artist

- en:Artist collective

- en:Beauty

- en:Biennial

- en:Biennale

- en:Culinary art

- en:Definition of music

- en:Figurative art

- en:Fine art

- en:Landscape art

- en:Modern art

- en:Nudity in art

- en:Socialist Realism

- en:What Is Art?

- en:Video art

Bibliography

[編集]- en:Arthur Danto, The Abuse of Beauty: Aesthetics and the Concept of Art. 2003

- John Whitehead. Grasping for the Wind. 2001

- Noel Carroll, Theories of Art Today. 2000

- Evelyn Hatcher, ed. Art as Culture: An Introduction to the Anthropology of Art. 1999

- Nina, Felshin, ed. But is it Art? 1995

- Stephen Davies, Definitions of Art. 1991

- Oscar Wilde, "Intentions"

Further reading

[編集]- ArteyCritica.com. Forum of art (in Spanish, sub-forums in English)

- en:Carl Jung, Man and His Symbols

- en:Benedetto Croce, Aesthetic as Science of Expression and General Linguistic, 1902

- en:Władysław Tatarkiewicz, A History of Six Ideas: an Essay in Aesthetics, translated from the Polish by en:Christopher Kasparek, The Hague, Martinus Nijhoff, 1980.

- en:Leo Tolstoy, en:What Is Art?, 1897

- Kleiner, Gardner, Mamiya and Tansey (2004). Art Through the Ages, Twelfth Edition (2 volumes). Wadsworth. ISBN 0-534-64095-8 (vol 1) and ISBN 0-534-64091-5 (vol 2)

External links

[編集]- In-depth directory of art

- Art and Artist Files in the Smithsonian Libraries Collection (2005) Smithsonian Digital Libraries

References and notes

[編集]- ^ a b c d Modern Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology. ed. Francis Frascina and Charles Harrison, 1982.

- ^ Hatcher, 1999

- ^ Britannica Online

- ^ Davies, 1991 and Carroll, 2000

- ^ Danto, 2003

- ^ Novitz, 1992

- ^ Controversial Art in History.

- ^ http://books.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,,1035752,00.html Does time fly?Peter Galison's Empires of Time, a historical survey of Einstein and Poincaré

- ^ Contradictions of the Enlightenment: Darwin, Freud, Einstein and modern art - Fordham University

カテゴリ: en:Category:Arts