利用者:Halowand/Hitomazu

投稿する前にここで試し書きをしています。 翻訳途中のものを置くこともしばしばあります。

ヴァルキリードーム(Valkyrie Dome)とはクイーンモードランドの東部、南緯77度30分 東経37度30分 / 南緯77.500度 東経37.500度にあり、ドームふじ、ドームF、Valkyrjedomenとしても知られている。海抜は3810メートルで、東南極氷床で二番目に高いアイスドーム、または頂上である。また、分氷嶺でもある。ドームFにはドームふじ基地という観測基地があり、日本によって運営されている。

発見と命名

[編集]ヴァルキリードームとは、クイーンモードランド東部にあるアイスドームで、高さ約3700メートルである1963年から64年にかけて、ソビエト南極探検が、ドームの北の雪上、標高3600メートル以上の地点を横切った。特徴は1967年から79年にかけて、SPRI-NSF-TUD 航空電波氷河観測プログラムにより記録された。戦闘中に死んだ者をヴァルハラへ運ぶ北欧神話のヴァルキリーにちなんでヴァルキリードームと命名された。

環境

[編集]南極台地の上にあるということ、そしてその高い標高により、ヴァルキリードームは地球で最も寒い場所の一つである。気温は、夏は滅多に-30°C 以上にならず、冬は-80°C以下に落ち込むことがある。年間平均気温は-54.3°C。気候は寒地荒原で、非常に乾燥しており、年間降水量は水に換算して25ミリで、すべて氷の結晶として降る[1]。

ドームふじ基地

[編集]ドームふじ基地(Dome Fuji Station)は、元々はドームふじ観測拠点 (Dome Fuji observation base)として1995年1月に設立され、2004年4月1日にドームふじ基地へと名前を変えた。場所は南緯77度19分 東経39度42分 / 南緯77.317度 東経39.700度。昭和基地とは約1000キロメートル離れている。

Glaciology

[編集]ドームふじにおける深層氷床コアの掘削は1995年8月に始り、1996年12月に深度2503メートルに到達した。この最初のコアは、340000年前までカバーしている[2][3]。

東南極にあるドームふじからとれるコアの質は、is excellent even in the brittle zone from 500 to 860 m deep, where the ice is fragile during the 'in situ' core-cutting procedure.[4]

A second deep core was started in 2003. Drilling was carried out during four subsequent austral summers from 2003/2004 until 2006/2007, and by then a depth of 3035.22 m was reached. The drill did not hit the bedrock, but rock particles and refrozen water have been found in the deepest ice, indicating that the bedrock is very close to the bottom of the borehole. This core greatly extends the climatic record of the first core, and, according to a first, preliminary dating, it reaches back until 720,000 years.[5] The ice of the second Valkyrie Dome core is therefore the second-oldest ice ever recovered, only outranged by the EPICA Dome C core.

関連項目

[編集]- Troll (research station)

- Valhalla

- Valkyrie

- Asuka Station (Antarctica)

- Mizuho Station (Antarctica)

- Showa Station (Antarctica)

- Vostok Station

- Climate of Antarctica

出典

[編集]- ^ Watanabe, O.; and 11 others (2003). "General tendencies of stable isotopes and major chemical constituents of the Dome Fuji deep ice core". Global scale climate and environmental study through polar deep ice cores. Tokyo, Japan: National Institute of Polar Research. pp. 1–24.

- ^ Dome-F Deep Coring Group (1998). “Deep ice-core drilling at Dome Fuji and glaciological studies in east Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica”. Annals of Glaciology 27: 333–337.

- ^ Kawamura, K.; and 17 others (2007). “Northern Hemisphere forcing of climatic cycles in Antarctica over the past 360,000 years”. Nature 448 (7156): 912–916. doi:10.1038/nature06015. PMID 17713531.

- ^ Watanabe O, Kamiyama K, Motoyama H, Fujii Y, Shoji H, Satow K (Jun 1999). “The paleoclimate record in the ice core at Dome Fuji station, East Antarctica”. Annu Glac. 29 (1): 176–8. doi:10.3189/172756499781821553.

- ^ Motoyama, H. (2007). “The second deep ice coring project at Dome Fuji, Antarctica”. Scientific Drilling 5: 41–43. doi:10.5194/sd-5-41-2007.

外部リンク

[編集]- Dome Fuji Deep Ice Coring Project

- Dome Fuji page of the World Data Center (WDC) for Paleoclimatology, contains downloadable data for the first core

- National Institute of Polar Research, Tokyo, Japan

- Institute of Low Temperature Science, Sapporo, Japan

- COMNAP Antarctic Facilities

- COMNAP Antarctic Facilities Map

Template:Antarctic research stations

セーリングにおけるクリッパールートとは、クリッパーという船が、ヨーロッパと、極東及びオーストラリア及びニュージーランドの間を帆走するときの、伝統的な航路である。吠える40度の強い西風を使うために、ルートは南極海を西から東へと走っている。多くの船と水兵が、航路状態の劣悪さによって行方しれずになっている。とりわけ、クリッパーがヨーロッパへ向かうときに回頭しなければならないホーン岬で、行方しれずになっている。

蒸気船の導入と、スエズ運河及びパナマ運河の開通により、クリッパールートは商業的には使われなくなった。しかしながら、世界一周をする際の最速の帆走航路としては健在であり、en:Around Aloneやen:Vendée Globeのような、いくつかの有名なヨットレースのルートになっている。

オーストラリアとニュージーランド

[編集]

イングランドからオーストラリアやニュージーランドヘ向かうクリッパールートは、, returning via ホーン岬, offered captains the 最速の世界一周, and hence potentially the greatest rewards; many穀物と羊毛と金 clippers sailed this route, returning home with valuable cargos in a relatively short time. しかしながら、this route, passing south of the three great capes and running for much of its length through the 南極海, also carried the greatest risks, exposing ships to the hazards of fierce winds, 巨大な波, and 氷山. This combination of the fastest ships, the highest risks, and the greatest rewards combined to give this route a particular aura of ロマンスとドラマ.[1]

Outbound

[編集]ルートはイングランドから東大西洋を赤道へ向けて南下し、, crossing at about the position of サンペドロ・サンパウロ群島, around 東経20度線付近の. この地点までの3,275マイル (5,271 km)を帆走する好タイムは約21日間。しかしながら、不運な船だと熱帯収束帯を越えるのにもう三週間ほどかかってしまうことがある[2]。

ルートは西大西洋を南下し、自然に出来た風と海流の循環に従って、 Trindadeの近くを通過し、そしてトリスタン・ダ・クーニャを過ぎたら南東に曲がる[3][4]。ルートは南緯40度線付近で本初子午線を越え、クリッパーが吠える40度に入るのはプリマスから約6,500マイル (10,500 km)帆走した地点である。この地点までを帆走する好タイムは約43日間[5]。

Once into the forties, a ship was also inside the ice zone, the area of the 南極海 where there was a significant chance of encountering 氷山. Safety would dictate keeping to the north edge of this zone, roughly along the parallel of 南緯40度線; しかしながら、喜望峰からオーストラリアへのgreat circle routeは, 南緯60度線まで南下する。この をたどった場合は1,000マイル (1,600 km)のショートカットになり、さらにより強い風を受けることが出来る。 Ship's masters would therefore go as far south as they dared, weighing the risk of ice against a fast passage.[6]

Theクリッパーships bound for オーストラリアとニュージーランド would call at a variety of ports. A ship sailing from Plymouth to シドニー, を例にあげると、 would cover around 13,750マイル (22,130 km); a fast time for this passage 約百日間ほどになる[7]。 Cutty Sark made the fastest passage on this route by a clipper, in 72 日間[8]。 Thermopylae made the slightly shorter passage from London to メルボルン, 13,150マイル (21,160 km), in just 61 days in 1868–69.[9]

以下の地図traces the outbound route of the 1874年 voyage from ロンドン to アデレード, South Australia, of the clipper ship City of Adelaide, which today is the world's oldest surviving clipper ship. The latitudes and longitudes are obtained from the surviving diary of 21 year old passenger James McLauchlan.[10]

Homeward

[編集]The return passage continued east from Australia; ships stopping at ウエリントン would pass through the クック海峡, but otherwise this tricky passage was avoided, with ships passing instead around the south end of New Zealand.[11] Once again, eastbound ships would be running more or less within the ice zone, staying as far south as possible for the shortest route and strongest winds. Most ships stayed north of the latitude of Cape Horn, at 56 degrees south, following a southward dip in the ice zone as they approached the Horn.[12]

The Horn itself had, and still has, an infamous reputation among sailors. The strong winds and currents which flow perpetually around the Southern Ocean without interruption are funnelled by the Horn into the relatively narrow ドレーク海峡; coupled with turbulent cyclones coming off the Andes, and the shallow water near the Horn, this combination of factors can create violently hazardous conditions for ships.[13]

Those ships which survived the Horn then made the passage back up the Atlantic, following the natural wind circulation up the eastern South Atlantic and more westerly in the North Atlantic. A good run for the 14,750マイル (23,740 km) from Sydney to Plymouth would be around 100 days; Cutty Sark made it in 84 days, and Thermopylae in 77 days.[9][14] Lightning made the longer passage from Melbourne to Liverpool in 65 days in 1854–55, completing a circumnavigation of the world in 5 months, 9 days, which included 20 days spent in port.[15]

The later windjammers, which were usually large four-masted barques optimized on cargo and handling rather than running, usually made the voyage in 90 to 105 days. The fastest recorded time on Great Grain Races was on Finnish four-masted barque Parma, 83 days in 1933 [1]. Her master on the voyage was the legendary Finnish captain Ruben de Cloux.[16]

The following map traces the homeward route of the 1867 voyage from Adelaide to London of the clipper ship City of Adelaide. The latitudes and longitudes were obtained from the surviving diary of 15 year old passenger Frederick Bullock.[17] A visual comparison of this map with the previous map shows that the City of Adelaide travelled a figure-of-eight route around the North and South Atlantic Oceans, following the natural circulation of winds and currents. On other homeward voyages the City of Adelaide sometimes travelled around Cape Horn.[18][19]

Variations

[編集]

The route sailed by a sailing ship was always heavily dictated by the wind conditions, which are generally reliable from the west in the forties and fifties. Even here, however, winds are variable, and the precise route and distance sailed would depend on the conditions on a particular voyage. Ships in the deep Southern Ocean could find themselves faced with persistent headwinds, or even becalmed.

Sailing ships attempting to go against the route, however, could have even greater problems. In 1922, Garthwray attempted to sail west around the Horn carrying cargo from the Firth of Forth to Iquique, Chile. After two attempts to round the Horn the "wrong way", her master gave up and sailed east instead, reaching Chile from the other direction.[20]

Even more remarkable was the voyage of Garthneill in 1919. Attempting to sail from Melbourne to Bunbury, Western Australia, a distance of 2,000マイル (3,200 km), she was unable to make way against the forties winds south of Australia, and was faced by strong westerly winds again when she attempted to pass through the Torres Strait to the north. She finally turned and sailed the other way, passing the Pacific, Cape Horn, the Atlantic, the Cape of Good Hope, and the Indian Ocean to finally arrive in Bunbury after 76 days at sea.[20][21]

It is also worth pointing out that the first person to circumnavigate the world solo, Joshua Slocum in the Spray, did it rounding Cape Horn from east to west. His was not the fastest circumnavigation on record, and he took more than one try to get through Cape Horn.

Modern use of the route

[編集]The introduction of steam ships, and the opening of the Suez and Panama Canals, spelled the demise of the clipper route as a major trade route. However, it remains the fastest sailing route around the world, and so the growth in recreational long-distance sailing has brought about a revival of sailing on the route.

The first person to attempt a high-speed circumnavigation of the clipper route was Francis Chichester. Chichester was already a notable aviation pioneer, who had flown solo from London to Sydney, and also a pioneer of single-handed yacht racing, being one of the founders of the Single-Handed Trans-Atlantic Race (the OSTAR). After the success of the OSTAR, Chichester started looking into a clipper-route circumnavigation. He wanted to make the fastest ever circumnavigation in a small boat, but specifically set himself the goal of beating a "fast" clipper-ship passage of 100 days to Sydney.[22] He set off in 1966, and completed the run to Sydney in 107 days; after a stop of 48 days, he returned via Cape Horn in 119 days.[23][24]

Chichester's success inspired several others to attempt the next logical step: a non-stop single-handed circumnavigation along the clipper route. The result was the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race, which was not only the first single-handed round-the world yacht race, but in fact the first round-the world yacht race in any format. Possibly the strangest yacht race ever run, it culminated in a successful non-stop circumnavigation by just one competitor, Robin Knox-Johnston, who became the first person to sail the clipper route single-handed and non-stop. However Bernard Moitessier decided to withdraw from the Race after rounding Cape Horn in a promising Position. Instead of heading home to Europe he decided to continue to Tahiti, completing his circumnaigation south of Cape Town and doing actual one and a half when arriving in Papeete.

Today, there are several major races held regularly along the clipper route. The Volvo Ocean Race is a crewed race with stops which sails the clipper route every four years. Two single-handed races, inspired by Chichester and the Golden Globe race, are the Around Alone, which circumnavigates with stops, and the Vendée Globe, which is non-stop.

In 2005年3月, Bruno Peyron and crew on the catamaran Orange II set a new world record for a circumnavigation by the clipper route, of 50 days, 16 hours, 20 minutes and 4 seconds.[25]

また同じく2005年, Ellen MacArthur set a new world record for a single-handed non-stop circumnavigation in the trimaran B&Q/Castorama. Her time along the clipper route of 71 days, 14 hours, 18 minutes 33 seconds is the fastest ever circumnavigation of the world by a single-hander.[26] While this record still leaves MacArthur as the fastest female singlehanded circumnavigator, in 2008 Francis Joyon eclipsed that record in the trimaran IDEC with a time of 57 days, 13 hours, 34 minutes 6 seconds.[26]

関連項目

[編集]出典

[編集]- ^ Along the Clipper Way, Francis Chichester; pages 15–16. Hodder & Stoughton, 1966. ISBN 0-340-00191-7

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; pages 44–45.

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; page 47.

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; page 54.

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; pages 57–58.

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; pages 74–75.

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; page 7.

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; page 8.

- ^ a b Along the Clipper Way; page 68.

- ^ “Diary of James Anderson McLauchlan”. City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 3 April 2012閲覧。

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; page 121.

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; page 134.

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; pages 151–152.

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; pages 7–8.

- ^ Along the Clipper Way; page 69.

- ^ A Visual Encyclopedia of Nautical Terms under Sail, Crown Publishers, Inc., New York, 1978, section 11

- ^ “Diary of Frederick Bullock”. City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 3 April 2012閲覧。

- ^ “Wilcox Family”. City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 3 April 2012閲覧。

- ^ “Voyage to London in 1878”. City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 3 April 2012閲覧。

- ^ a b Along the Clipper Way; pages 72–73., quoted from Falmouth for Orders by Alan Villiers

- ^ Garthneill – Garden Island, from the South Australia department of Environment and Heritage

- ^ Gipsy Moth Circles the World, Sir Francis Chichester; page 6. International Marine, 2001. ISBN 0-07-136449-8

- ^ Gipsy Moth Circles the World; page 105.

- ^ Gipsy Moth Circles the World; page 218.

- ^ Orange II smashes the round the world sailing record, from Yachts and Yachting

- ^ a b WSSRC Ratified Passage Records – "Round the World, non stop, singlehanded", from the World Sailing Speed Record Council

Images

[編集][Category:Clippers]] [Category:Maritime history]] [Category:Navigation]] [Category:Age of Sail]]

| Yamato 000593 | |

|---|---|

やまと 000593 – 13.7 kg (30 lb) - 立方体は1センチ立方1 cm (0.39 in) (NASA; 2012年) | |

| 種類 | エイコンドライト |

| 分類 | 火星隕石[1] |

| 型 | ナクライト[1] |

| 構造的分類 | 火成岩[2] |

| 成分 |

輝石 85% [2] カンラン石 10% |

| 衝撃変成 | S3[2] |

| 風化分類 | B[3] |

| 発見国 | 南極[1] |

| 発見場所 | Yamato Glacier[1] |

| 座標 | 南緯71度30分 東経35度40分 / 南緯71.500度 東経35.667度座標: 南緯71度30分 東経35度40分 / 南緯71.500度 東経35.667度 [3][4] |

| 落下観測 | なし |

| 落下日 | 5万年前[1] |

| 発見日 | 2000年[1] |

| 総回収量(TKW) | 13.7 kg (30 lb)[1] |

| プロジェクト:地球科学/Portal:地球科学 | |

Yamato 000593 (または Y000593)は、火星隕石の中で二番目に大きい南極隕石である[1][5][6]。研究によると火星隕石は13億年前に火星の溶岩流によって生成された。約1200万年前に、火星に別の隕石が衝突し、やまと 000593が火星の地表面から宇宙空間へ弾き出された。その後やまと 000593は、約5万年前に地球の南極に落ちた。隕石の質量は13.7 kg (30 lb)で、かつて火星に水があったことの証拠が含まれていることがわかった[1][5][6][7] 。

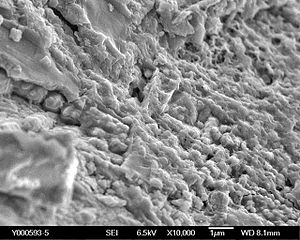

顕微鏡レベルで見ると、炭素を多く含む球状の構造が見つかり、その周囲には球状構造はなかった。この炭素に富む球状構造と、同じく観察された微小な管構造は、NASAの科学者によると、生命活動によって形成された可能性がある[1][5][6]。

発見と命名

[編集]日本の第41次南極地域観測隊が2000年12月後半にやまと山脈のやまと氷河で発見した[1][8]。

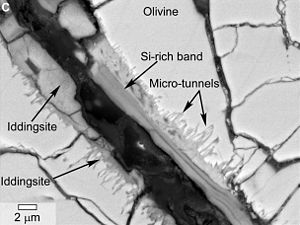

解説

[編集]隕石の重さは13.7 kg (30 lb)[1]。非角礫化された堆積火成岩で、主に引き伸ばされた普通輝石、輝石の固溶体でできている[8]。日本の国立極地研究所の科学者は2003年に、この隕石には液体の水の中で玄武岩が風化してできたイジングサイトが含まれている、と報告した[8]。コレに加えてNASAの研究員はreported in 2014年2月に、炭素の多い球状構造が幾層ものイジングサイトに包まれていることを発見した, as well as microtubular features emanating from イジングサイト veins displaying curved, undulating shapes consistent with 生物変化 textures observed in 地球の玄武岩のglass.[1]。しかしながら、科学的なコンセンサスでは、「形態論だけを単純な生命探知の道具として使うことはできないTemplate:訳語不安点」ということになっている[9][10][11]。

Interpretation of morphology is notoriously subjective, and its use alone has led to numerous errors of interpretation.[9] According to the NASA team, the presence of carbon and lack of corresponding cations is consistent with the occurrence of 有機物 embedded in イジングサイト.[5] The NASA researchers indicated that 質量分析法 may provide deeper insight into the nature of the carbon, and could distinguish between abiotic and biologic carbon incorporation and alteration.[5]

分類

[編集]この火星隕石は火成岩のエイコンドライトの中のナクライトに分類されている[2][1]。

ギャラリー

[編集]関連項目

[編集]- Allan Hills 84001

- Astrobiology

- Glossary of meteoritics

- Life on Mars

- List of Martian meteorites

- List of meteorites on Mars

- Nakhla meteorite

- Panspermia

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Webster, Guy (February 27, 2014). “NASA Scientists Find Evidence of Water in Meteorite, Reviving Debate Over Life on Mars”. NASA. February 27, 2014閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Yamato meteorite (PDF) The Astromaterials Acquisition and Curation Office, NASA.

- ^ a b “Meteoritical Bulletin Database - Yamato 000593”. The Meteoritical Society. Lunar and Planetary Institute (February 26, 2014). February 28, 2014閲覧。

- ^ Yamato 000593 Natural History Museum, UK. The Catalogue of Meteorites.

- ^ a b c d e White, Lauren M.; Gibson, Everett K.; Thomnas-Keprta, Kathie L.; Clemett, Simon J.; McKay, David (February 19, 2014). “Putative Indigenous Carbon-Bearing Alteration Features in Martian Meteorite Yamato 000593”. Astrobiology 14 (2): 170-181. doi:10.1089/ast.2011.0733 February 27, 2014閲覧。.

- ^ a b c Gannon, Megan (February 28, 2014). “Mars Meteorite with Odd 'Tunnels' & 'Spheres' Revives Debate Over Ancient Martian Life”. Space.com. February 28, 2014閲覧。

- ^ Mikouchi, T.; E. Koizumi; A. Monkawa; Y. Ueda (March 2003). “Mineralogy and petrology of Yamato 000593: Comparison with other Martian nakhlite meteorites”. Antarctic meteorite research 16: 34-57.

- ^ a b c Imae, N.; Y. Ikeda; K. Shinoda; H. Kojima (2003). “Yamato nahklites: Petrography and mineralogy”. Antarctic Meteorite Research 16: 13-33 March 1, 2014閲覧。.

- ^ a b “Morphological behavior of inorganic precipitation systems - Instruments, Methods, and Missions for Astrobiology II”. SPIE Proceedings Proc. SPIE 3755. (December 30, 1999). doi:10.1117/12.375088 January 15, 2013閲覧. "It is concluded that "morphology cannot be used unambiguously as a tool for primitive life detection.""

- ^ Agresti, House, Jögi, Kudryavstev, McKeegan, Runnegar, Schopf, Wdowiak (December 3, 2008). “Detection and geochemical characterization of Earth’s earliest life”. NASA Astrobiology Institute (NASA) January 15, 2013閲覧。

- ^ J. William Schopf, Anatoliy B. Kudryavtsev, Andrew D. Czaja , Abhishek B. Tripathi (April 28, 2007). “Evidence of Archean life: Stromatolites and microfossils” (PDF). Precambrian Research 158: 141–155. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.009 January 15, 2013閲覧。.

外部リンク

[編集]- Yamato meteorite (PDF) The Astromaterials Acquisition and Curation Office, NASA.

Template:Meteorites Template:Meteorites by name Template:Mars Template:Astrobiology Template:Extraterrestrial life

[Category:火星]] [Category:南極隕石]]