利用者:Makochan12.9/下書き2

|

ここはMakochan12.9さんの利用者サンドボックスです。編集を試したり下書きを置いておいたりするための場所であり、百科事典の記事ではありません。ただし、公開の場ですので、許諾されていない文章の転載はご遠慮ください。

登録利用者は自分用の利用者サンドボックスを作成できます(サンドボックスを作成する、解説)。 この利用者の下書き:User:Makochan12.9/sandbox その他のサンドボックス: 共用サンドボックス | モジュールサンドボックス 記事がある程度できあがったら、編集方針を確認して、新規ページを作成しましょう。 |

| |

| 名称 |

|

|---|---|

| 任務種別 | Uncrewed lunar orbital test flight |

| 運用者 | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 2022-156A |

| SATCAT № | 54257 |

| ウェブサイト | www |

| 任務期間 | |

| 飛行距離 | 1.3 million miles (2.1 million kilometers) |

| 特性 | |

| 宇宙機 | Orion CM-002 |

| 宇宙機種別 | Orion MPCV |

| 製造者 | |

| 任務開始 | |

| 打ち上げ日 | November 16, 2022, 06:47:44 UTC (1:47 am EST)[3] |

| ロケット | Space Launch System Block 1 |

| 打上げ場所 | Kennedy Space Center, LC-39B |

| 任務終了 | |

| 回収担当 | Template:USS[5] |

| 着陸日 | December 11, 2022, 17:40:30 UTC (9:40:30 am PST)[2] |

| 着陸地点 | Pacific Ocean off Baja California[4] |

| 軌道特性 | |

| 参照座標 | Selenocentric |

| 体制 | Distant retrograde orbit |

| 軌道周期 | 14 days |

| Moonのフライバイ | |

| 宇宙船搭載構成物 | Orion |

| 最接近 | November 21, 2022, 12:57 UTC[6] |

| 距離 | 130 km |

| Moonオービター | |

| 宇宙船搭載構成物 | Orion |

| 軌道投入 | November 25, 2022, 21:52 UTC[7] |

| 軌道脱出 | December 1, 2022, 21:53 UTC[8] |

| Moonのフライバイ | |

| 宇宙船搭載構成物 | Orion |

| 最接近 | December 5, 2022, 16:43 UTC[9] |

| 距離 | 128 km |

Artemis 1 mission patch | |

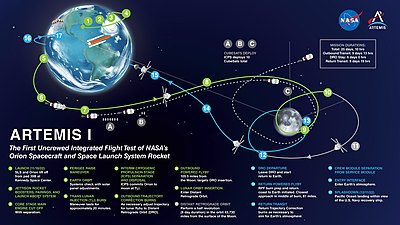

アルテミス1号(アルテミス1ごう、英: Artemis I、旧称:Exploration Mission-1, EM-1)は月周回を目的とした無人飛行試験ミッションの名称である。NASAのアルテミス計画の最初に行われたミッションであり、アポロ計画の終了から50年経ての月探査への復帰の意味を持つミッションであった。また、オリオン宇宙船とスペース・ローンチ・システム(SLS)を用いて行った最初の総合飛行試験でもあり、その後のアルテミス計画のミッションにおけるオリオン宇宙船や特にオリオン宇宙船の熱シールドの試験を行うことを目的としていた。そのためオリオン宇宙船並びにスペース・ローンチ・システムも[10]

Artemis 1, officially Artemis I[11] and formerly Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1),[12] was an uncrewed Moon-orbiting mission. As the first major spaceflight of NASA's Artemis program, Artemis 1 marked the agency's return to lunar exploration after the conclusion of the Apollo program five decades earlier. It was the first integrated flight test of the Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System (SLS) rocket,[note 1] and its main objective was to test the Orion spacecraft, especially its heat shield,[13] in preparation for subsequent Artemis missions. These missions seek to reestablish a human presence on the Moon and demonstrate technologies and business approaches needed for future scientific studies, including exploration of Mars.[14]

The Orion spacecraft for Artemis 1 was stacked on October 20, 2021,[15] and on August 17, 2022, the fully stacked vehicle was rolled out for launch after a series of delays caused by difficulties in pre-flight testing. The first two launch attempts were canceled due to a faulty engine temperature reading on August 29, 2022, and a hydrogen leak during fueling on September 3, 2022.[16] Artemis 1 was launched on November 16, 2022, at 06:47:44 UTC (01:47:44 EST).[17]

Artemis 1 launched from Launch Complex 39B at the Kennedy Space Center.[18] After reaching Earth orbit, the upper stage carrying the Orion spacecraft separated and performed a trans-lunar injection before releasing Orion and deploying ten CubeSat satellites. Orion completed one flyby of the Moon on November 21, entered a distant retrograde orbit for six days, and completed a second flyby of the Moon on December 5.[19]

The Orion spacecraft then returned and reentered the Earth's atmosphere with the protection of its heat shield, splashing down in the Pacific Ocean on December 11.[20] The mission aims to certify Orion and the Space Launch System for crewed flights beginning with Artemis 2,[21] which is scheduled to perform a crewed lunar flyby in 2024. After Artemis 2, Artemis 3 will involve a crewed lunar landing, the first in five decades since Apollo 17.

Mission profile

[編集]Artemis 1 was launched on the Block 1 variant of the Space Launch System.[22] The Block 1 vehicle consists of a core stage, two five-segment solid rocket boosters (SRBs) and an upper stage. The core stage uses four RS-25D engines, all of which have previously flown on Space Shuttle missions. The core and boosters together produce 39,000 kN (8,800,000 lbf), or about 4,000 metric tons of thrust at liftoff. The upper stage, known as the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS), is based on the Delta Cryogenic Second Stage and is powered by a single RL10B-2 engine on the Artemis 1 mission.[23]

Once in orbit, the ICPS fired its engine to perform a trans-lunar injection (TLI) burn, which placed the Orion spacecraft and 10 CubeSats on a trajectory to the Moon. Orion then separated from the ICPS and continued its coast into lunar space. Following Orion separation, the ICPS Stage Adapter deployed ten CubeSats for conducting scientific research and performing technology demonstrations.[24]

The Orion spacecraft spent approximately three weeks in space, including six days in a distant retrograde orbit (DRO) around the Moon.[25] It came within approximately 130 km (80 mi) of the lunar surface (closest approach)[6] and achieved a maximum distance from Earth of 432,210 km (268,563 mi).[1][26]

| Date | Time (UTC) | Event |

|---|---|---|

Launch | ||

| November 16 | 06:47:44 | Liftoff |

| 06:49:56 | Solid rocket booster separation | |

| 06:50:55 | Service module fairing jettisoned | |

| 06:51:00 | Launch abort system (LAS) jettisoned | |

| 06:55:47 | Core stage main engine cutoff (MECO) | |

| 06:55:59 | Core stage and ICPS separation | |

| 07:05:53 – 07:17:53 | Orion solar array deployment | |

| 07:40:40 – 07:41:02 | Perigee raise maneuver | |

| 08:17:11 – 08:35:11 | ICPS Trans-lunar injection (TLI) burn | |

| 08:45:20 | Orion/ICPS separation | |

| 08:46:42 | Upper-stage separation burn | |

| 10:09:20 | ICPS disposal burn | |

| ||

| Moon outbound transit | ||

| November 16 | 14:35:15 | First trajectory correction burn |

| November 17–20 | Outbound coasting phase | |

| November 21 | 12:44 | Outbound powered flyby burn[6] |

| Orbiting Moon | ||

| November 21–24 | Transit to DRO | |

| November 25–30 | Distant retrograde orbit | |

| December 1 | 21:53 | DRO departure burn[8] |

| December 1–4 | Exiting DRO | |

| Earth return | ||

| December 5 | 16:43 | Close approach[9] |

| December 5–11 | Return transit | |

| December 11 | 17:40:30 | Splashdown at Pacific Ocean |

Mission profile animation

[編集]Background

[編集]

Artemis 1 was outlined by NASA as Exploration Mission 1 (EM-1) in 2012, at which point it was set to launch in 2017[27][note 2] as the first planned flight of the Space Launch System and the second uncrewed test flight of the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle. The initial plans for EM-1 called for a circumlunar trajectory during a seven-day mission.[29][30]

In January 2013, it was announced that the Orion spacecraft's service module was to be built by the European Space Agency and named the European Service Module.[31] In mid-November 2014, construction of the SLS core stage began at NASA's Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF).[32] In January 2015, NASA and Lockheed Martin announced that the primary structure in the Orion spacecraft used on Artemis 1 would be up to 25% lighter compared to the previous one (EFT-1). This would be achieved by reducing the number of cone panels from six (EFT-1) to three (EM-1), reducing the total number of welds from 19 to 7[33] and saving the additional mass of the weld material. Other savings would be due to revising its various components and wiring. For Artemis 1, the Orion spacecraft was to be outfitted with a complete life support system and crew seats but would be left uncrewed.[34]

In February 2017, NASA began investigating the feasibility of a crewed launch as the first SLS flight.[22] It would have had a crew of two astronauts and the flight time would have been shorter than the uncrewed version.[35] However, after a months-long feasibility study, NASA rejected the proposal, citing cost as the primary issue, and continued with the plan to fly the first SLS mission uncrewed.[36]

In March 2019, then-NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine proposed moving the Orion spacecraft from SLS to commercial rockets, either the Falcon Heavy or Delta IV Heavy, to comply with the schedule.[37][38] The mission would require two launches: one to place the Orion spacecraft into orbit around the Earth, and a second carrying an upper stage. The two would then dock while in Earth orbit, and the upper stage would ignite to send Orion to the Moon.[39] The idea was eventually scrapped.[40] One challenge with this option would be carrying out that docking, as Orion is not planned to carry a docking mechanism until Artemis 3.[41] The concept was shelved in mid-2019, due to another study's conclusion that it would further delay the mission.[42]

Ground testing

[編集]

The core stage for Artemis 1, built at Michoud Assembly Facility by Boeing, had all four engines attached in November 2019[43] and was declared finished one month later.[44] The core stage left the facility to undergo the Green Run test series at Stennis Space Center, consisting of eight tests of increasing complexity:[45]

- Modal testing (vibration tests)

- Avionics (electronic systems)

- Fail-safe systems

- Propulsion (without firing of the engines)

- Thrust vector control system (moving and rotating engines)

- Launch countdown simulation

- Wet dress rehearsal, with propellant

- Static fire of the engines for eight minutes

The first test was performed in January 2020,[45][46] and subsequent Green Run tests proceeded without issue. On January 16, 2021, a year later, the eighth and final test was performed, but the engines shut down after running for one minute.[47] This was caused by pressure in the hydraulic system used for the engines' thrust vector control system dropping below the limits set for the test. However, the limits were conservative – if such an anomaly occurred in launch, the rocket would still fly normally.[48] The static fire test was performed again on March 18, 2021, this time achieving a full-duration eight-minute burn.[49] The core subsequently departed the Stennis Space Center on April 24, 2021, on route to the Kennedy Space Center.[50]

Assembly

[編集]

SLS/Orion is assembled by stacking its major sub-assemblies atop a mobile launcher platform inside the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB). First, the seven components of each of the two boosters are stacked. The core stage is then stacked and is supported by the boosters. The interstage and upper stage are stacked atop the core, and the Orion spacecraft is then stacked onto the upper stage.

The Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage was the first part of the SLS to be delivered to the Kennedy Space Center in July 2017.[51] Three years later, all of the SLS's solid rocket booster segments were shipped by train to the Kennedy Space Center on June 12, 2020,[52] and the SLS launch vehicle stage adapter (LVSA) was delivered by barge one month later on July 29.[53] The assembly of the SLS took place at the Vehicle Assembly Building's High Bay 3, beginning with the placement of the two bottom solid rocket booster segments onto Mobile Launcher-1 on November 23.[54] Assembly of the boosters was temporarily paused due to the core stage Green Run test delays before being resumed on January 7, 2021,[55] and the boosters' stacking was completed by March 2.[56]

The SLS core stage for the mission, CS-1, arrived at the launch site on the Pegasus barge on April 27, 2021, after the successful conclusion of Green Run tests. It was moved to the VAB low bay for refurbishment and stacking preparations on April 29.[57] The stage was then stacked with its boosters on June 12. The stage adapter was stacked on the Core Stage on June 22. The ICPS upper stage was stacked on July 6. Following the completion of umbilical retract testing and integrated modal testing, the Orion stage adapter with ten secondary payloads was stacked atop the upper stage on October 8.[58] This marked the first time a super-heavy-lift vehicle has been stacked inside NASA's VAB since the final Saturn V in 1973.

The Artemis 1 Orion spacecraft began fueling and pre-launch servicing in the Multi-Payload Processing Facility on January 16, 2021, following a handover to NASA Exploration Ground Systems (EGS).[59][60] On October 20, the Orion spacecraft, encapsulated under the launch abort system and aerodynamic cover, was rolled over to the VAB and stacked atop the SLS rocket, finishing the stacking of the Artemis 1 vehicle in High Bay 3.[61] During a period of extensive integrated testing and checkouts, one of the four RS-25 engine controllers failed, requiring a replacement and delaying the first rollout of the rocket.[62][63]

Launch preparations

[編集]

On March 17, 2022, Artemis 1 rolled out of High Bay 3 from the Vehicle Assembly Building for the first time to perform a pre-launch wet dress rehearsal (WDR). The initial WDR attempt, on April 3, was scrubbed due to a mobile launcher pressurization problem.[64] A second attempt to complete the test was scrubbed on April 4, after problems with supplying gaseous nitrogen to the launch complex, liquid oxygen temperatures, and a vent valve stuck in a closed position.[65]

During preparations for a third attempt, a helium check valve on the ICPS upper stage was kept in a semi-open position by a small piece of rubber originating from one of the mobile launcher's umbilical arms, forcing test conductors to delay fueling the stage until the valve could be replaced in the VAB.[66][67] The third attempt to finish the test did not include fueling the upper stage. The rocket's liquid oxygen tank started loading successfully. However, during the loading of liquid hydrogen on the core stage, a leak was discovered on the tail service mast umbilical plate, located on the mobile launcher at the base of the rocket, forcing another early end to the test.[68][69]

NASA elected to roll the vehicle back to the VAB to repair the hydrogen leak and the ICPS helium check valve while upgrading the nitrogen supply at LC-39B after prolonged outages on the three previous wet dress rehearsals. Artemis 1 was rolled back to the VAB on April 26.[70][71][72] After the repairs and upgrades were complete the Artemis 1 vehicle rolled out to LC-39B for a second time on June 6 to complete the test.[73]

During the fourth wet dress rehearsal attempt on June 20, the rocket was fully loaded with propellant on both stages. Still, due to a hydrogen leak on the quick-disconnect connection of the tail service mast umbilical, the countdown could not reach the planned T-9.3 seconds mark and was stopped automatically at T-29 seconds. NASA mission managers soon determined they had completed almost all planned test objectives and declared the WDR campaign complete.[74]

On July 2, the Artemis 1 stack was rolled back to the VAB for final launch preparations and to fix the hydrogen leak on the quick disconnect ahead of a launch targeted in two launch windows: August 29 and September 5.[75][76] The SLS passed flight readiness review on August 23, checking out five days before the first launch opportunity.[77]

Initial launch attempts

[編集]Fueling was scheduled to commence just after midnight on August 29, 2022, but was delayed an hour due to offshore storms, only beginning at 1:13 am EDT. Before the planned launch at 8:33 am, Engine 3 of the rocket's four engines was observed to be above the maximum allowable temperature limit for launch.[78][79] Other technical difficulties involved an eleven-minute communications delay between the spacecraft and ground control, a fuel leak, and a crack on the insulating foam of the connection joints between the liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen tanks.[78][80][81] NASA scrubbed the launch after an unplanned hold and the two-hour launch window expired.[82] An investigation revealed that a sensor not used to determine launch readiness was faulty, and displayed an erroneously high temperature for Engine 3.[79]

Following the first attempt, a second launch attempt was scheduled for the afternoon of September 3.[83] The launch window would have opened at 2:17 pm EDT (18:17 UTC), and lasted for two hours.[84] The launch was scrubbed at 11:17 am EDT due to a fuel supply line leak in a service arm connecting to the engine section.[85][16] The cause of the leak was uncertain. Mission operators investigated whether an overpressurization of the liquid hydrogen line of the quick-disconnect interface during the launch attempt may have damaged a seal, allowing hydrogen to escape.[86]

Launch operators decided on the date for the next launch attempt; the earliest possible opportunity was September 19[87][88][89] until mission managers declared that September 27, and then September 30, would be the absolute earliest date, NASA having successfully repaired the leak.[90][91] A launch in September would have required that the Eastern Range of the United States Space Force agree to an extension on certification of the rocket's flight termination system, which destroys the rocket should it move off-course and towards a populated area;[86] this was carried out on September 22.[92] However, unfavorable forecasts of the trajectory of then-Tropical Storm Ian led launch managers to call off the September 27 launch attempt and begin preparations for the stack's rollback to the VAB.[93] On the morning of September 26, the decision was made to roll back later that evening.[94][95]

On November 12, following another delay due to Hurricane Nicole, NASA launch managers decided to request launch opportunities for November 16 and 19. They initially requested an opportunity for the 14th but were prevented by then-Tropical Storm Nicole.[2] As the storm approached, NASA decided to leave the rocket at the launch pad, citing a low probability that wind speeds would exceed the rocket's design limits.[96] Wind speeds were expected to reach 29 mph (47 km/h), with gusts up to 46 mph (74 km/h). Nicole made landfall as a category one hurricane on November 9, with sustained wind speeds at Kennedy Space Center reaching 85 mph (137 km/h), and gusts up to 100 mph (160 km/h). After the storm cleared, NASA inspected the rocket for physical damage and conducted electronic health checks.[97][98][99] On November 15, the mission management team gave a "go" to begin fully preparing for launch, and the main tanking procedures began at 3:30 pm EST (20:30 UTC).[100]

Flight

[編集]Launch

[編集]

At 6:47:44 UTC (1:47:44 am EST) on November 16, 2022, Artemis 1 successfully launched from Launch Complex 39B (LC-39B) at the Kennedy Space Center.[3] Artemis 1 was the first launch from LC-39B since Ares I-X. The Orion spacecraft and ICPS were both placed into a nominal orbit after separating from the Space Launch System, achieving orbit approximately 8 and a half minutes after launch.[101]

Outbound flight

[編集]

Eighty-nine minutes after liftoff, the ICPS fired for approximately eighteen minutes in a trans-lunar injection (TLI) maneuver. Orion then separated from the expended stage and fired its auxiliary thrusters to move safely away as it started its journey to the Moon.[102] The 10 CubeSat secondary payloads were then deployed from the Orion Stage Adapter, attached to the ICPS.[103] The ICPS conducted a final maneuver at three and a half hours after launch to dispose itself into a heliocentric orbit.[104]

On November 20 at 19:09 UTC, the Orion spacecraft entered the lunar sphere of influence, where the influence of the Moon's gravity on the spacecraft is greater than that of Earth.[105]

Lunar orbit

[編集]

On November 21, Orion lost communication with NASA as it passed behind the Moon from 12:25 through 12:59 UTC. There, during an automatically controlled maneuver, the first of several trajectory-altering burns, called an "outbound powered flyby burn",[105] to transition Orion to a distant retrograde orbit began at 12:44 UTC. The orbital maneuvering system engine fired for two minutes and thirty seconds. While operating autonomously, Orion made its closest lunar approach of approximately 130 km (81 mi) above the surface at 12:57 UTC.[106][107] The spacecraft performed another burn on November 25, firing the orbital maneuvering system (OMS) for one minute and twenty-eight seconds, changing Orion's velocity by 363 ft/s (398 km/h) finally entering orbit.[108] On November 26, at 13:42 UTC, Orion broke the record for the farthest distance from Earth traveled by an Earth-returning human-rated spacecraft. The record was formerly held by the Apollo 13 mission at 400,171 km (248,655 mi).[108][109][7]

On November 28, Orion reached a distance of 432,210 km (268,563 mi) from Earth, the maximum distance achieved during the mission.[110] On November 30, the Orion spacecraft performed a maintenance burn to maintain its trajectory and decrease its velocity for a planned burn on December 1, at 21:53 UTC, to depart its distant retrograde orbit around the Moon, beginning its journey back to Earth.[111]

On December 5 at 16:43 UTC the spacecraft reached 128 km (80 mi) from the lunar surface at its closest approach right before an earthbound burn, the "powered return flyby burn", to leave the zone of lunar gravitational influence. The spacecraft once again passed behind the Moon, losing communications with mission control for about half an hour.[112] Shortly before the flyby, Orion experienced an electrical anomaly, which was soon resolved.[113]

Return flight

[編集]On December 6 at 7:29 UTC, Orion exited the lunar sphere of influence. It then conducted a minor course correction burn and an inspection of the crew module's thermal protection system and the ESM.[114] Over the next few days the mission control team continued to conduct system checks and prepared for reentry and splashdown. On December 10, mission planners announced that the final landing site would be near Guadalupe Island off the Baja peninsula in Mexico.[115] The final trajectory correction burn of six total trajectory burns throughout the mission took place the next day five hours before reentry.[116]

Reentry and splashdown

[編集]

The spacecraft separated from its service module at around 17:00 UTC on December 11 and then reentered Earth's atmosphere at 17:20 UTC travelling near 40,000 km/h (25,000 mph).[117] It was the first United States use of a "skip entry", a form of non-ballistic atmospheric entry into the atmosphere, pioneered by Zond 7, in which two phases of deceleration would expose human occupants to relatively less intense G-forces than would be experienced during an Apollo-style reentry.[118] The Orion capsule splashed down at 17:40 UTC (9:40 am PST) west of Baja California near Guadalupe Island.[20] Following splashdown, NASA personnel and the crew of Template:USS recovered the spacecraft after planned ocean testing of the capsule.[119] The recovery team spent about two hours performing tests in open water and imaging the craft, namely to investigate signs of atmospheric re-entry, then used a winch and several tending lines to pull the craft into a securing assembly in the well dock of the USS Portland. The recovery team included personnel from the US Navy, Space Force, Kennedy Space Center, Johnson Space Center, and Lockheed Martin Space.[120] On December 13, the Orion capsule arrived at the Port of San Diego.[121]

Payloads

[編集]The Orion spacecraft carried three astronaut-like mannequins equipped with sensors to provide data on what crew members may experience during a trip to the Moon.[122] The first mannequin, called "Captain Moonikin Campos" (named after Arturo Campos, a NASA engineer during the Apollo program),[123] occupied the commander's seat inside Orion and was equipped with two radiation sensors in its Orion Crew Survival System suit, which astronauts will wear during launch, entry, and other dynamic phases of their missions. The commander's seat also had sensors to record acceleration and vibration data during the mission.[124]

Alongside Moonikin were two phantom torsos: Helga and Zohar, who took part in the Matroshka AstroRad Radiation Experiment (MARE), in which NASA, together with the German Aerospace Center and the Israel Space Agency, measured the radiation exposure during the mission. Zohar was shielded with the Astrorad radiation vest and equipped with sensors to determine radiation risks. Helga did not wear a vest. The phantoms measured the radiation exposure of body location, with both passive and active dosimeters distributed at sensitive and high stem cell-concentration tissues.[125] The test provided data on radiation levels during missions to the Moon while testing the effectiveness of the vest.[126] In addition to the three mannequins, Orion carried a plush doll of NASA's Snoopy as zero-g indicator[127] and a Shaun the Sheep toy[128] representing the ESA's European Service Module contribution to the mission.

Besides these functional payloads, Artemis 1 also carried commemorative stickers, patches, seeds, and flags from contractors and space agencies worldwide.[129] A technology demonstration called Callisto, named after the mythical figure associated with Artemis, developed by Lockheed Martin in collaboration with Amazon and Cisco, was also aboard. Callisto used video conferencing software to transmit audio and video from mission control and used the Alexa virtual assistant to respond to the audio messages. In addition, the public could submit messages to be displayed on Callisto during the mission.[130]Template:Update after

Cubesats

[編集]

Ten low-cost CubeSats, all in six-unit configurations,[131] flew as secondary payloads.[132] They were carried within the Stage Adapter above the second stage. Two were selected through NASA's Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships, three through the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate, two through the Science Mission Directorate, and three from submissions by NASA's international partners.[133] These CubeSats are:[132]

- ArgoMoon, designed by Argotec and coordinated by the Italian Space Agency, is designed to image the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage.

- BioSentinel contains yeast cards that will be rehydrated in space, designed to detect, measure, and compare the effects of deep space radiation.

- CubeSat for Solar Particles, designed by the Southwest Research Institute, will orbit the Sun in interplanetary space and study its particles and magnetic activity.

- EQUULEUS, designed by Japan's JAXA and the University of Tokyo, will image the Earth's plasmasphere, impact craters on the Moon's far side, and small trajectory maneuvers near the Moon.

- Lunar IceCube, a lunar orbiter designed by Morehead State University, will use its infrared spectrometer to detect water and organic compounds in the lunar surface and exosphere.

- Lunar Polar Hydrogen Mapper ("LunaH-Map"), selected by the NASA SIMPLEx program,[134] a lunar orbiter designed by Arizona State University, will search for evidence of lunar water ice inside permanently shadowed craters using its neutron detector.

- Near-Earth Asteroid Scout, designed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, was a solar sail that would have flown by a near-Earth asteroid. Communication with the spacecraft had not been successful and NEA Scout is now considered lost.

- OMOTENASHI, designed by JAXA, a lunar probe which would have attempted to land using solid rocket motors, but failed to function properly.

- LunIR, designed by Lockheed Martin, is to fly by the Moon and collect its surface thermography.

- Team Miles, designed by Fluid and Reason LLC, will demonstrate low-thrust plasma propulsion in deep space.

Three other CubeSats were originally planned to launch on Artemis 1 but missed the integration deadline, and will have to find alternative flights to the Moon. The stage adapter contained thirteen CubeSat deployers in total.[135]

- Cislunar Explorers would demonstrate the viability of water electrolysis propulsion and interplanetary optical navigation to orbit the Moon. It was designed by Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.[136]

- Lunar Flashlight is a lunar orbiter that would seek exposed water ice and map its concentration at the 1–2 km (0.62–1.24 mi) scale within the permanently shadowed regions of the lunar south pole.[137][138] Remanifested on Hakuto-R Mission 1 on a Falcon 9.[139]

- Earth Escape Explorer would demonstrate long-distance communications while in heliocentric orbit. It was designed by the University of Colorado Boulder.[136]

Media outreach

[編集]

The Artemis 1 mission patch was created by NASA designers of the SLS, Orion spacecraft and Exploration Ground Systems teams. The silver border represents the color of the Orion spacecraft; at the center, the SLS and Orion are depicted. Three lightning towers surrounding the rocket symbolize Launch Complex 39B, from which Artemis 1 will launch. The red and blue mission trajectories encompassing the white full Moon represent Americans and people in the European Space Agency who work on Artemis 1.[140]

The Artemis 1 flight is frequently marketed as the beginning of Artemis's "Moon to Mars" program,[141][142] though there is no concrete plan for a crewed mission to Mars within NASA as of 2022.[143] To raise public awareness, NASA made a website for the public to get a digital boarding pass of the mission. The names submitted were written to a flash drive stored inside the Orion spacecraft.[144][145] Also aboard the capsule is a digital copy of the 14,000 entries for the Moon Pod Essay Contest hosted by Future Engineers for NASA.[146]

Gallery

[編集]-

The SLS for Artemis 1 from the bottom of the pad

-

Artemis 1 a few hours before liftoff

-

The Moon as seen from Orion on the sixth day of the mission

-

Inside Orion with Callisto

-

Orion right before loss of signal on the first flyby

-

Close up picture from Orion near closest approach on the first flyby

-

Artemis 1 looking back at the Moon and Earth at its maximum distance from Earth on November 28, 2022.

-

Mission control on flight day 14

-

Lunar mare and craters captured on Orion's return flyby

-

Rilles and craters near lunar terminator

-

The Moon showing its terminator right after the return flyby

-

Artemis 1 images the Earth before reentry

-

Orion descending down to the Pacific Ocean

-

Splashdown of Orion

-

Orion off the coast of Baja California shortly after splashdown

See also

[編集]Notes

[編集]- ^ An Orion capsule was flown in 2014, but not the entire Orion spacecraft.

- ^ The Space Launch System was originally mandated by Congress in the NASA Authorization Act of 2010 to be ready for flight before the end of 2016.[28]

References

[編集]- ^ a b c “Artemis 1 Press Kit”. November 15, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 16, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b c “NASA Prepares Rocket, Spacecraft Ahead of Tropical Storm Nicole, Re-targets Launch”. NASA (November 8, 2022). November 8, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 8, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b Roulette, Joey; Gorman, Steve (November 16, 2022). “NASA's next-generation Artemis mission heads to moon on debut test flight”. Reuters. オリジナルのNovember 16, 2022時点におけるアーカイブ。 November 16, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I launch guide: What to expect”. The Planetary Society. August 15, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 24, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis 1 flight to moon depends on precision rocket firings to pull off a complex trajectory” (英語). CBS News. August 29, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 31, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Artemis I – Flight Day Five: Orion Enters Lunar Sphere of Influence Ahead of Lunar Flyby”. NASA (November 20, 2022). December 5, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 21, 2022閲覧。 “The outbound powered flyby will begin at 7:44 am, with Orion's closest approach to the Moon targeted for 7:57 am,...”

- ^ a b “Artemis I – Flight Day 11: Orion Surpasses Apollo 13 Record Distance from Earth – Artemis” (英語). blogs.nasa.gov. November 27, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 27, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b “Artemis I Flight Day 16 – Orion Successfully Completes Distant Retrograde Departure Burn”. NASA (December 1, 2022). December 6, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 2, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b “Artemis I – Flight Day 20: Orion Conducts Return Powered Flyby”. NASA (December 5, 2022). December 6, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 6, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Hambleton, Kathryn (2018年3月7日). “Around the Moon with NASA’s First Launch of SLS with Orion”. NASA. 2021年10月6日閲覧。

- ^ Artemis: brand book (Report). Washington, D.C.: NASA. 2019. NP-2019-07-2735-HQ.

MISSION NAMING CONVENTION: While Apollo mission patches used numbers and roman numerals throughout the program, Artemis mission names will use a roman numeral convention.

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ Hambleton, Kathryn (February 20, 2018). “Artemis I Overview”. NASA. August 17, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 24, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “NASA: Artemis I”. NASA. March 15, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 17, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Dunbar, Brian (July 23, 2019). “What is Artemis?”. NASA. August 7, 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 17, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “NASA Fully Stacked for Moon Mission, Readies for Artemis I”. NASA (October 23, 2021). November 17, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 17, 2022閲覧。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (September 3, 2022). “Second Artemis 1 launch attempt scrubbed”. SpaceNews. January 16, 2023時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 4, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis 1”. NASA. December 19, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 17, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis 1 Presskit”. November 15, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 31, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Sloss, Philip (November 1, 2021). “Inside Artemis 1's complex launch windows and constraints”. NASASpaceflight.com. March 25, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。March 25, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b “NASA's Artemis I moon mission ends as Orion capsule splashes down in Pacific Ocean” (英語). Boston 25 News (December 11, 2022). December 11, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 11, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Clark, Stephen (May 18, 2020). “NASA will likely add a rendezvous test to the first piloted Orion space mission”. Spaceflight Now. July 8, 2020時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。May 19, 2020閲覧。

- ^ a b “NASA to Study Adding Crew to First Flight of SLS and Orion”. NASA (February 15, 2017). April 22, 2018時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。February 15, 2017閲覧。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ Harbaugh, Jennifer (December 13, 2021). “Space Launch System”. NASA. November 8, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 9, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Harbaugh, Jennifer (October 4, 2021). “All Artemis I Secondary Payloads Installed in Rocket's Orion Stage Adapter”. NASA. July 15, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。October 6, 2021閲覧。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ “The Ins and Outs of NASA's First Launch of SLS and Orion”. NASA (November 27, 2015). February 22, 2020時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。May 3, 2016閲覧。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ Cheshier, Leah (November 28, 2022). “Artemis I — Flight Day 13: Orion Goes the (Max) Distance”. blogs.nasa.gov. January 16, 2023時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 15, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Exploration Mission 1: SLS and Orion mission to the Moon outlined”. NASASpaceFlight.com. NASASpaceFlight (February 29, 2012). August 24, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Rockefeller, Jay (August 5, 2010). “S.3729 – 111th Congress (2009–2010): National Aeronautics and Space Administration Authorization Act of 2010”. Congress.gov. Library of Congress. May 29, 2015時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Hill, Bill (March 2012). “Exploration Systems Development Status”. NASA Advisory Council. February 11, 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 21, 2012閲覧。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ Singer, Jody (April 25, 2012). “Status of NASA's Space Launch System”. University of Texas. December 18, 2013時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 5, 2012閲覧。

- ^ “NASA Signs Agreement for a European-Provided Orion Service Module” (英語). NASA (January 17, 2013). March 28, 2014時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 24, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “SLS Engine Section Barrel Hot off the Vertical Weld Center at Michoud”. NASA. November 19, 2014時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 16, 2014閲覧。

- ^ Barrett, Josh (January 13, 2015). “Orion program manager talks EFT-1 in Huntsville”. WAAY. オリジナルのJanuary 18, 2015時点におけるアーカイブ。 January 14, 2015閲覧。

- ^ “Engineers resolve Orion will 'lose weight' in 2015”. WAFF. (January 13, 2015). オリジナルのAugust 8, 2018時点におけるアーカイブ。 January 15, 2015閲覧。

- ^ “NASA Kicks Off Study to Add Crew to First Flight of Orion, SLS”. NASA (February 24, 2017). February 28, 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。February 27, 2017閲覧。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris (May 12, 2017). “NASA will not put a crew on EM-1, cites cost – not safety – as main reason”. NASASpaceFlight.com. July 3, 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。May 19, 2020閲覧。

- ^ King, Ledyard (May 14, 2019). “NASA names new moon landing mission 'Artemis' as Trump administration asks for US$1.6 billion”. August 3, 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 29, 2020閲覧。

- ^ Grush, Loren (July 18, 2019). “NASA's daunting to-do list for sending people back to the Moon”. December 7, 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 29, 2020閲覧。

- ^ Foust, Jeff (March 13, 2019). “NASA considering flying Orion on commercial launch vehicles”. SpaceNews. August 27, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。March 13, 2019閲覧。

- ^ Sloss, Philip (April 19, 2019). “NASA Launch Services Program outlines the alternative launcher review for EM-1”. NASASpaceFlight.com. オリジナルのMay 3, 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。 June 9, 2019閲覧。

- ^ Foust, Jeff (March 13, 2019). “NASA considering flying Orion on commercial launch vehicles”. SpaceNews. August 27, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。March 13, 2019閲覧。

- ^ Sloss, Philip (April 19, 2019). “NASA Launch Services Program outlines the alternative launcher review for EM-1”. NASASpaceFlight.com. オリジナルのMay 3, 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。 June 9, 2019閲覧。

- ^ “All Four Engines Are Attached to the SLS Core Stage for Artemis I Mission”. NASA (November 8, 2019). November 12, 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 12, 2019閲覧。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ Foust, Jeff (December 10, 2019). “SLS Core Stage Declared Ready for Launch in 2021”. SpaceNews. August 27, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 27, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b Harbaugh, Jennifer (May 20, 2020). “NASA's SLS Core Stage Green Run Tests Critical Systems For Artemis I”. NASA. April 26, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 27, 2022閲覧。

この記事には現在パブリックドメインとなった次の出版物からの記述が含まれています。

この記事には現在パブリックドメインとなった次の出版物からの記述が含まれています。

- ^ Rincon, Paul (January 9, 2020). “Nasa Moon rocket core leaves for testing”. BBC News. オリジナルのJanuary 9, 2020時点におけるアーカイブ。 January 9, 2020閲覧。

- ^ Foust, Jeff (January 16, 2021). “Green Run hotfire test ends early”. SpaceNews. October 3, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 27, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “SLS: NASA finds cause of 'megarocket' test shutdown”. BBC News (January 20, 2021). January 20, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。January 20, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Foust, Jeff (March 18, 2021). “NASA performs full-duration SLS Green Run static-fire test”. SpaceNews. August 27, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 27, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Dunbar, Brian (April 29, 2021). “Space Launch System Core Stage Arrives at the Kennedy Space Center”. NASA. May 7, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。June 1, 2021閲覧。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ “SLS Upper Stage set to take up residence in the former home of ISS modules” (July 11, 2017). August 7, 2020時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。February 15, 2020閲覧。

- ^ Sloss, Philip (June 19, 2020). “EGS begins Artemis 1 launch processing of SLS Booster hardware”. NASASpaceFlight.com. March 29, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。May 28, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Sloss, Philip (August 5, 2020). “LVSA arrives at KSC, NASA EGS readies final pre-stacking preparations for Artemis 1”. NASASpaceFlight.com. May 19, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。May 28, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Sloss, Philip (November 27, 2020). “EGS, Jacobs begin vehicle integration for Artemis 1 launch”. NASASpaceFlight.com. December 20, 2020時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 29, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Sloss, Philip (December 4, 2020). “New Artemis 1 schedule uncertainty as NASA EGS ready to continue SLS Booster stacking”. NASASpaceFlight.com. August 14, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。May 28, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Sempsrott, Danielle (March 9, 2021). “Mammoth Artemis I Rocket Boosters Stacked on Mobile Launcher” (英語). NASA's blog. NASA. August 25, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 27, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Sloss, Philip (May 6, 2021). “NASA EGS, Jacobs preparing SLS Core Stage for Artemis 1 stacking”. NASASpaceFlight.com. June 11, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。May 28, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Clark, Stephen (October 12, 2021). “Adapter structure with 10 CubeSats installed on top of Artemis moon rocket”. Spaceflight Now. October 22, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。October 23, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Sloss, Philip (March 27, 2021). “EGS synchronizing Artemis 1 Orion, SLS Booster preps with Core Stage schedule”. NASASpaceFlight.com. May 20, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。May 28, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Bergin, Chris (March 29, 2021). “Following troubled childhood, Orion trio preparing for flight”. NASASpaceFlight.com. April 2, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。May 28, 2021閲覧。

- ^ Sloss, Philip (October 21, 2021). “Artemis 1 Orion joins SLS to complete vehicle stack” (英語). NASASpaceFlight.com. December 30, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 27, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “EGS, Jacobs begin Artemis 1 pre-launch testing and checkout push” (November 11, 2021). July 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Engine controller replacement details behind Artemis 1 launch delay” (December 22, 2021). July 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I Wet Dress Rehearsal Scrub – Artemis”. July 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “NASA Prepares for Next Artemis I Wet Dress Rehearsal Attempt – Artemis”. July 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I Wet Dress Rehearsal Update – Artemis”. July 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I Rocket, Spacecraft Prepare for Return to Launch Pad to Finish Test – Artemis”. July 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I WDR Update: Third Test Attempt Concluded – Artemis”. July 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “NASA calls off modified Artemis 1 Wet Dress Rehearsal for hydrogen leak” (April 14, 2022). July 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I Update: Teams Extending Current Hold, Gaseous Nitrogen Supply Reestablished – Artemis”. June 10, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis 1 vehicle heads back to VAB while NASA discusses what to do next” (April 25, 2022). June 23, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I Moon Rocket Arrives at Vehicle Assembly Building – Artemis”. June 24, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “NASA's Artemis 1 moon rocket returns to launch pad for crucial tests” (英語). Space.com (June 6, 2022). June 10, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。June 10, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “NASA declares SLS countdown rehearsal complete” (June 24, 2022). August 27, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “NASA not planning another Artemis 1 countdown dress rehearsal – Spaceflight Now”. July 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “SLS rolled back to VAB for final launch preparations” (July 2, 2022). July 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Foust, Jeff (August 23, 2022). “Artemis 1 passes flight readiness review” (英語). SpaceNews. August 29, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 29, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b Ashley Strickland (August 29, 2022). “Today's Artemis I launch has been scrubbed after engine issue”. CNN. オリジナルのAugust 29, 2022時点におけるアーカイブ。 August 29, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b “NASA Ready to Try Artemis I Again on Saturday and See What the Day Brings” (英語). September 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 2, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Speck, Emilee (August 23, 2022). “Artemis 1 countdown resumes for Saturday launch; weather forecast improves”. Fox Weather. August 28, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Tariq Malik (August 29, 2022). “NASA calls off Artemis 1 moon rocket launch over engine cooling issue” (英語). Space.com. オリジナルのAugust 29, 2022時点におけるアーカイブ。 August 29, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Anthony Cuthbertson; Vishwam Sankaran; Johanna Chisholm; Jon Kelvey (August 29, 2022). “Nasa scrambles to fix Moon rocket issues ahead of Artemis launch – live” (英語). The Independent. オリジナルのAugust 29, 2022時点におけるアーカイブ。 August 29, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Ashley Strickland (September 2, 2022). “Artemis I launch team is ready for another 'try' on Saturday”. CNN. September 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 2, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Foust, Jeff (August 30, 2022). “Next Artemis 1 launch attempt set for Sept. 3”. SpaceNews. September 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 31, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I Launch Attempt Scrubbed”. NASA blog. NASA. December 28, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 3, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen. “NASA officials evaluating late September launch dates for Artemis 1 moon mission – Spaceflight Now” (英語). September 9, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Davenport, Christian (September 3, 2022). “Artemis I mission faces weeks of delay after launch is scrubbed”. The Washington Post. オリジナルのSeptember 5, 2022時点におけるアーカイブ。 September 6, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Greenfieldboyce, Nell; Hernandez, Joe (September 3, 2022). “NASA won't try to launch the Artemis 1 moon mission again for at least a few weeks” (英語). NPR. オリジナルのSeptember 6, 2022時点におけるアーカイブ。 September 6, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Kraft, Rachel (May 16, 2022). “Artemis I Mission Availability”. NASA. December 11, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 6, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris (September 8, 2022). “NASA discusses path to SLS repairs as launch uncertainty looms for September, October”. NASASpaceflight. September 8, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 8, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “NASA Adjusts Dates for Artemis I Cryogenic Demonstration Test and Launch; Progress at Pad Continues”. NASA (September 12, 2022). September 12, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 13, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Zizo, Christie (September 22, 2022). “NASA moves ahead with Artemis launch attempt next week with eye on weather”. WKMG. September 23, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 24, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Kraft, Rachel (September 24, 2022). “Artemis I Managers Wave Off Sept. 27 Launch, Preparing for Rollback – Artemis”. NASA Blogs. NASA. September 24, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 24, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “NASA to Roll Artemis I Rocket and Spacecraft Back to VAB Tonight – Artemis” (英語). blogs.nasa.gov. September 26, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 26, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Foust, Jeff (September 26, 2022). “SLS to roll back to VAB as hurricane approaches Florida”. SpaceNews. January 16, 2023時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 27, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “NASA Prepares Rocket, Spacecraft Ahead of Tropical Storm Nicole, Re-targets Launch”. NASA (November 8, 2022). November 8, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 10, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Teams Conduct Check-outs, Preparations Ahead of Next Artemis I Launch Attempt – Artemis”. NASA Blogs. NASA (November 11, 2022). November 11, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 12, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Fisher, Kristin; Wattles, Jackie (November 10, 2022). “NASA inspects Artemis I rocket after Hurricane Nicole”. CNN. オリジナルのNovember 11, 2022時点におけるアーカイブ。 November 10, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Tribou, Richard (November 10, 2022). “Artemis I endures 100 mph gust on launch pad during Nicole landfall”. Orlando Sentinel. オリジナルのNovember 11, 2022時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Kraft, Rachel (November 14, 2022). “Managers Give "Go" to Proceed Toward Launch, Countdown Progressing – Artemis”. NASA Blogs. NASA. December 11, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 15, 2022閲覧。

- ^ (英語) Artemis I Launch to the Moon (Official NASA Broadcast) – Nov. 16, 2022, オリジナルのNovember 16, 2022時点におけるアーカイブ。 November 16, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Orion on Its Way to the Moon – Artemis”. blogs.nasa.gov. November 17, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 17, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Davenport, Justin (November 16, 2022). “Artemis I releases 10 cubesats, including a Moon lander, for technology and research”. NASASpaceFlight.com. November 18, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 18, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “SLS makes successful debut flight, sending Artemis I to the Moon”. NASASpaceFlight.com (November 16, 2022). November 15, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 18, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b “Artemis I – Flight Day Five: Orion Enters Lunar Sphere of Influence Ahead of Lunar Flyby – Artemis”. blogs.nasa.gov. December 5, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 21, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Cheshier, Leah (November 19, 2022). “Artemis I – Flight Day Four: Testing WiFi Signals, Radiator System, GO for Outbound Powered Flyby”. nasa.gov. November 20, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 20, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Cheshier, Leah (November 21, 2022). “Orion Successfully Completes Lunar Flyby, Re-acquires Signal with Earth”. nasa.gov. November 21, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 21, 2022閲覧。

- ^ a b “Flight Day 10: Orion Enters Distant Retrograde Orbit – Artemis”. blogs.nasa.gov. November 25, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 26, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Dodson, Gerelle (November 25, 2022). “NASA to Share Artemis I Update with Orion at Farthest Point from Earth”. NASA. November 26, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。November 26, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Cheshier, Leah (November 28, 2022). “Artemis I — Flight Day 13: Orion Goes the (Max) Distance”. NASA. December 1, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 2, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I Flight Day 15 – Team Polls "Go" For Distant Retrograde Orbit Departure – Artemis” (英語). blogs.nasa.gov. December 1, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 1, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Wall, Mike (December 5, 2022). “NASA's Artemis 1 Orion spacecraft completes crucial moon flyby maneuver for trip home” (英語). Space.com. December 5, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 6, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (December 5, 2022). “Artemis 1 Orion spacecraft suffered power blip hours before its close lunar flyby” (英語). Space.com. December 5, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 6, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I – Flight Day 21: Orion Leaves Lunar Sphere of Influence, Heads for Home – Artemis” (英語). blogs.nasa.gov. December 11, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 11, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I Flight Day 24: Orion Heads Home – Artemis” (英語). blogs.nasa.gov. December 11, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 11, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I – Flight Day 25: Orion in Home Stretch of Journey – Artemis” (英語). blogs.nasa.gov. December 11, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 11, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Here's how NASA's Artemis 1 Orion spacecraft will splash down to end its moon mission in 8 not-so-easy steps” (英語). Space.com (December 10, 2022). December 11, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 11, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “NASA's Orion capsule heads for splashdown after Artemis I flight around moon”. Reuters (December 11, 2022). December 11, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 11, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Nasa's Orion capsule on target for splashdown” (英語). BBC News. (December 11, 2022). オリジナルのDecember 11, 2022時点におけるアーカイブ。 December 11, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I Update: Orion Secured Inside USS Portland Ahead of Return to Shore – Artemis” (英語). blogs.nasa.gov. December 15, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 14, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Bravo, Christina. “Welcome to San Diego, Orion: NASA's Space Capsule Arrives to Port by Navy Ship” (英語). NBC 7 San Diego. December 14, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。December 14, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Pasztor, Andy (April 17, 2018). “U.S., Israeli Space Agencies Join Forces to Protect Astronauts From Radiation”. The Wall Street Journal. オリジナルのAugust 29, 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。 June 21, 2018閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I launch guide: What to expect”. The Planetary Society. August 9, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 9, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Purposeful Passengers Hitch a Ride on NASA's Artemis I Mission”. NASA (August 15, 2022). August 15, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 28, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Berger, Thomas (11–12 October 2017). Exploration Missions and Radiation (PDF). International Symposium for Personal and Commercial Spaceflight. Las Cruces, New Mexico: ISPCS. 2018年6月22日時点のオリジナル (PDF)よりアーカイブ。2018年6月22日閲覧。

- ^ “Orion "Passengers" on Artemis I to Test Radiation Vest for Deep Space Missions”. NASA (February 13, 2020). July 19, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 28, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Snoopy to Fly on NASA's Artemis I Moon Mission”. NASA (November 12, 2021). August 10, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 9, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Shaun the Sheep to fly on Artemis I lunar mission”. aardman.com. August 8, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 8, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Artemis I Official Flight Kit”. NASA. August 17, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 27, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “How to send a message into space aboard Artemis I” (英語). KUSA.com (August 26, 2022). September 3, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。September 2, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Foust, Jeff (August 8, 2019). “NASA seeking proposals for cubesats on second SLS launch”. SpaceNews. August 27, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 29, 2020閲覧。 “Unlike Artemis 1, which will fly six-unit cubesats only...”

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (October 12, 2021). “Adapter structure with 10 CubeSats installed on top of Artemis moon rocket”. Spaceflight Now. October 12, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 25, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Latifiyan, Pouya (August 2022). “Artemis 1 and space communications”. Qoqnoos Scientific Magazine: 3.

- ^ NASA, Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration Program Abstracts of selected proposals Archived November 17, 2022, at the Wayback Machine., August 8, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ “Three DIY CubeSats Score Rides on NASA's First Flight of Orion, Space Launch System”. NASA (June 8, 2017). August 6, 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。June 10, 2017閲覧。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ a b Ohana, Lavie (October 3, 2021). “Four Artemis I CubeSats miss their ride”. Space Scout. April 17, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。October 6, 2021閲覧。

- ^ “Lunar Flashlight”. Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute. NASA (2015). September 13, 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。May 23, 2015閲覧。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ Wall, Mike (October 9, 2014). “NASA Is Studying How to Mine the Moon for Water”. Space.com. オリジナルのNovember 11, 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。 May 23, 2015閲覧。

- ^ “NASA's Lunar Flashlight Ready to Search for the Moon's Water Ice”. NASA (October 28, 2022). October 28, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。October 29, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Hambleton, Kathryn (January 16, 2018). “Artemis 1 Identifier”. NASA. August 5, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 24, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “How NASA's Artemis program plans to return astronauts to the moon”. Science (August 22, 2022). August 24, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 25, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Northon, Karen (September 26, 2018). “NASA Unveils Sustainable Campaign to Return to Moon, on to Mars”. NASA. July 7, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 25, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Kelvey, Jon (September 3, 2022). “Nasa's Artemis moon mission explained”. The Independent. August 25, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 25, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Marples, Megan (March 11, 2022). “NASA will send your name around the moon. Here's how to sign up”. CNN. August 24, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 24, 2022閲覧。

- ^ Wall, Mike (March 3, 2022). “Your name can fly around the moon on NASA's Artemis 1 mission”. Space.com. August 24, 2022時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。August 24, 2022閲覧。

- ^ “Future Engineers: Moon Pod Essay Contest”. March 26, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。March 24, 2021閲覧。

External links

[編集]- URLが見つかりません。ここでURLを指定するかウィキデータに追加してください。

- Simulation of Artemis 1 Launch and CubeSat Deployment - YouTube

- Artemis Real-time Orbit Website, NASA

- Live Video Stream from the Artemis I Orion Spacecraft

Template:Artemis program Template:Orion program Template:Moon spacecraft Template:Orbital launches in 2022 Template:2022 in space