利用者:Nux-vomica 1007/フランボワイヤン式

フランボワイヤン式(フランス語: Flamboyant)は、1375年ごろから16世紀中期まで、中世後期からルネサンス期のヨーロッパで発展した後期ゴシック建築の一様式である[1]。この様式の語源となった、火焔(flamboyant)のようなかたちをした二重カーブのバー・トレーサリー[1][2]、ヴォールトにおけるアーチ型の装飾リブと、アコレードとよばれる装飾アーチの多用に特徴づけられる[3]。フランボワイヤン式の目立つ特徴である、火焔のようなトレーサリーのリブは、それ以前の様式であるレイヨナン式の曲線的なトレーサリーの影響を受けている[1]。非常に高く、幅の狭い尖頭アーチと破風、とりわけ二重カーブの葱花アーチも、この様式の建物で一般に見られる[2]。ヨーロッパのほとんどの地域で、フランボワイヤン式のような後期ゴシック様式は、レイヨナン式をはじめとするそれ以前の様式に取って代わった[4]。

この様式は特に大陸ヨーロッパで好まれた。15世紀から16世紀にかけて、フランス王国、カスティーリャ同君連合、ミラノ公国および中央ヨーロッパ諸国の建築家と石工は理論書やドローイング、旅行などを通して専門知識を交換し[5][6]、フランボワイヤン式の装飾とデザインをヨーロッパ全土に広めた[7][8]。著名なフランボワイヤン式の例としてはサント・シャペル(1485年–1498年)の西側バラ窓、ルーアンのサン=マクルー教会(1500年–1514年)西側ポーチ、トロワ大聖堂(16世紀初期)西面などがある。また、非常に初期の例としては、ヨーク・ミンスター(1338年–1339年)の西側大窓がある[1]。ほかの例としては、ブルゴス大聖堂(1482年–1494年)の元帥の礼拝堂、レピーヌのノートルダム寺院、シャルトル大聖堂北側尖塔、セゴビア大聖堂(1525年–)がある[9]。

後期ゴシック様式は、ペトル・パルレーシュの手がけたプラハの聖ヴィート大聖堂(1334年–)の建設をもって中央ヨーロッパに持ち込まれる。この聖堂の形式、すなわち豊麗で変化に富むトレーサリーと複雑な網目模様をなすリブ・ヴォールトは、大陸ヨーロッパの後期ゴシックに広く用いられ、聖堂参事会教会や聖堂、それに匹敵する規模と壮麗さをもつ都市の教区教会に模倣された[10]。葱花アーチの利用もなかんずく一般的だった[11]。

15世紀から16世紀初期にかけ、フランボワイヤン式の形態はフランスからイベリア半島に波及する。同地で発展したイザベル様式は、イザベル1世治世下のカスティーリャ王国における国家的建築の支配的形式となった。また、フランボワイヤン式の特徴はポルトガル王国のマヌエル様式にも現れる。中央ヨーロッパでは、フランボワイヤン式やイザベル様式と同時期にゾンダーゴティック様式が登場する。

「フランボワイヤン式」という言葉は1843年に、フランスの芸術家であるユスターシュ=ヤサント・ラングロワ(1777年–1837年)が最初に[12]、その後、1851年にイギリスの歴史家であるエドワード・オーガスタス・フリーマンが用いた[13]。建築史においては、フランボワイヤン式は14世紀晩期にあらわれ、レイヨナン式の次の段階にあたるフランスのゴシック建築の最終段階であり、16世紀初期にルネサンス建築が発展するまで優位にあったと考えられている[14]。

フランスにおけるフランボワイヤン式建築の特筆すべき例としては、パリのサント・シャペル西側バラ窓、サンス大聖堂とボーヴェ大聖堂のトランセプト、ヴァンセンヌのサント・シャペル、ヴァンドームのトリニテ修道院西側ファサードがある。世俗建築ではブールジュのジャック・クール宮殿や、パリのクリュニー館が知られる。 15世紀後半から16世紀初頭にかけては、イングランドにおいて装飾様式や垂直様式とよばれる現代的様式がうまれる。

起源

[編集]フランボワイヤン式の起源は詳らかではないものの[15]、フランス北部およびフランドル伯領で14世紀後期に登場したとみなされている[16]。これらの地域はイングランド王国と布交易をしていたほか、甥であるフランス王ヘンリー6世(1422年–1453年在位)の摂政をつとめたベッドフォード公爵ジョン・オブ・ランカスターの支配下となったこともあった[16]。異論もあるが、この直接的関係から、フランボワイヤン式の揺らめく炎のようなトレーサリーの図案は、イギリスの装飾様式に影響されたものであると考えられている[16]。さらに、ノルマンディー公国は13世紀までイングランドと同君連合を組んでおり、百年戦争がおこなわれていた1419年から1449年にかけて、同国の首都であったルーアンはイングランドの領土となっていた[17]。戦争の初期にベリー公ジャンは同国の捕虜となった[18]。ポワティエ公宮殿の暖炉やルーアン大聖堂西側ファサードの衝立のように並んだ上部部材にみられるよう、引き続く戦争は多くの文化交流の機会をもたらした[19]。

14世紀におけるトレーサリーの文様は、装飾様式(例:ヨーク・ミンスター西側ファサード)に影響された華麗な火焔様の形態か、垂直様式(例:キングス・カレッジ・チャペル)の「いかめしい板張り」かのいずれかであった[20]。ロバート・ボーク(Robert Bork)によれば、「大陸の建築家たちは、もっぱら装飾様式だけを借用した。この様式はイングランドでは1360年までにほとんど廃れていた」という[18]。フランスにおける格子様の形態の明確な拒絶は、同地においてこれと対照的な様式が意識されていたことを示す[18]。フランボワイヤン式の登場は漸進的なものであった。「原フランボワイヤン式」(proto-Flamboyant)といえる様式は、ルーアンのサン=トゥアン修道院北側トランセプト(1390年–1410年)の壁にみることができる[5]。流れるような二重カーブの形態は用いられていないものの、「8枚の二重ランセット形の板が中心の四つ葉模様を中心に渦巻いているように見える」[5]。このバラ窓の文様は動的にみえるが、二重カーブを基調とはしていない。この建築はノルマンディーにおける流麗な二重曲線の使用を先取りした、トレースリーの形態の初期の実験例である。イングランドが垂直様式に転換していくなか、王侯貴族が建てた宮殿は、フランス北部の聖堂よりもさらに、曲線的なトレーサリーをもつ「革新のための肥沃な土地」を提供した[19]。

フランス

[編集]「フランボワイヤン式」という用語は19世紀につくられ、フランスにおける記念碑的建造物のうち[21]、1380年から1515年までに建造された火焔様の曲線的なトレーサリーを有するものを指す。イングランドとの百年戦争(1337年–1444年)の時期に登場した様式であるが、16世紀初頭まで、大聖堂や教会、世俗建築の新造および増築の際に用いられた。フランボワイヤン式の特徴は華麗な表現のファサード、豪華な装飾のポーチ、塔、尖塔である。初期の例として、リオンにあるベリー公ジャンの城内礼拝堂(1382年)、ポワティエ公宮殿大広間の暖炉(1390年)、ジャン・ド・ラ・グランジュによるアミアン大聖堂(1375年)などがある[22]。

フランボワイヤン式だけで築造された最初期の建築物には、貴族の邸宅といったものもある[23]。ブールジュにある、国王会計方であったジャック・クールの宮殿(ジャック・クール館、1444年–1451年)は、居住用と公務用のウィングが中庭を囲むようにして組み合わされており、破風・タレット・煙突によって華やかに装飾されている[24]。ジャン・ド・デュノワにより1459年から1468年にかけて改築されたシャトーダン城には[25]、「サント・シャペル」と銘する礼拝堂があり、付随するファサードは火焔様のトレーサリーで装飾された窓を備えるほか、屋根窓にはフランス王家の象徴であるフルール・ド・リスもあしらわれている。もとクリュニー修道院長の邸宅で、のちに国立中世美術館となった、パリのクリュニー館もこうした建築の主要な例であり、礼拝堂・戸口・窓・塔・屋根の輪郭などにフランボワイヤン式の細部意匠がみられる[24]。フランスにおけるフランボワイヤン式世俗建築の後期の例としては、のちにルーアン司法宮(Palais de Justice of Rouen)として知られるようになるノルマンディー高等法院(1499年 - 1528年)がある。ロジェ・アンゴ(Roger Ango)とルーラン・ル・ルーにより設計され、クロケットを配した細長い小尖塔と、フルーロンで区切られた屋根窓(リュカルヌ)を有している[26]。

-

Flamboyant openwork tracery, fireplace and chimney, Salle des pas perdus, Palace of Poitiers (c. 1390)

-

Chapels commissioned by Jean de la Grange, northwest corner, Amiens Cathedral (c. 1375). Note the use of curvilinear mouchettes and soufflets at the top of the windows.

-

Palais Jacques Coeur, Bourges (1444–1451)

-

The Dunois staircase, Château de Châteaudun (1459–1468)

-

Gable window of the Hotel de Cluny, Paris (15th century)

-

Lucarne, west façade of the former Parliament of Normandy, now the Palais de Justice, Rouen (1499–1507)

In 15th-century France, few churches were constructed entirely in the Flamboyant style; it was more common to commission additions to existing structures. One exception is the Church of Saint-Maclou in Rouen, which was commissioned by the Dufour family during the English occupation of the town. It was designed by the master mason Pierre Robin, who was in charge of construction from 1434 until the church was consecrated in 1521.[27] The church, which is referred to as "monumental architecture in the miniature", has double-tiered flying buttresses, fully developed transept façades with portals, curvilinear rose windows, and a projecting polygonal west porch with openwork ogee gables.[28] The influence of Pierre Robin's design lasted into the 16th century,[5] when Roulland Le Roux oversaw work on the upper parts of the Tour de Beurre ("Butter Tower") (1485–1507) and the central portal (1507–1510) of Rouen Cathedral.[2] Increasing specialization in Gothic workshops and lodges led to the sophisticated forms characteristic of structures that were completed in the early 16th century, such as the south façade and porch of the Church of Notre-Dame de Louviers (1506–1510) and the north tower of Chartres Cathedral, which were designed by architect Jehan de Beauce (1507–1513).[29]

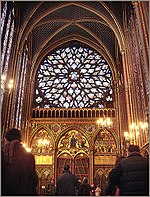

The style also appeared early Île-de-France. The west rose window of the Sainte-Chapelle was made between 1485 and 1498 by a glass artist known only as The Master of the Life of Saint-John the Baptist. It is nine meters in diameter, with 89 sections of glass, of which all but nine are original.The curling tracery of the window spills out onto the exterior of the west facade.[30]

where the Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes, a royal chapel constructed by King Charles V of France, is a notable example. It was located just outside Paris, next to the massive Château de Vincennes and was inspired by the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. The Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes had a single floor and the windows, consisting of curvilinear tracery, covered nearly all of the walls. Construction began in 1379 but was halted by the Hundred Years War and the window and west front were completed until 1552.[31] A significant Flamboyant landmark in Paris is the Tour Saint-Jacques, which is all that remains of the Church of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie ("Saint James of the butchers"), which was built 1509–23 and was located close to Les Halles, the Paris central market.[A]

In the Loire Valley, the west front of Tours Cathedral was a notable example of Flamboyant architecture. As the French Renaissance began with the royal chateaux along the Loire, the towers of the cathedral were updated with domes and lanterns in the new style, completed in 1507.[32]

-

West rose window of Sainte-Chapelle, Paris (1485-1498)

-

Facade of Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes (completed 1559)

-

The Butter Tower of Rouen Cathedral (1485–1507)

-

Rose window and façade of south transept, Sens Cathedral (1490–1518)

-

South porch of Notre-Dame de Louviers (1506–1510)

-

Detail of the North Tower of Chartres Cathedral (1507–1513)

-

Tour Saint-Jacques, Paris (1509–1523)

-

South rose window of Amiens Cathedral (16th c.)

-

North tower of Bourges Cathedral (1508-1515)

Beyond northern France, churches were also enlarged and updated with additions in the Flamboyant style. Due to its size and decoration, the abbey-church of Saint-Antoine in Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye (Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes) is one of the most significant examples of Gothic architecture in southeastern France. The five-aisled abbey-church was a key pilgrimage site in the Middle Ages because it contained the relics of Saint Anthony the Great, which were especially sought out by those who were suffering from "Saint Anthony's Fire" (ergot poisoning). Royal figures including Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor (1415), Louis XI of France (1475), and Anne of Brittany (1494) also visited the abbey-church.[33] The building's most prominent architectural feature is its monumental west façade, which was completed in the Flamboyant style in the 15th century. The façade has a central portal flanked by secondary portals and a large lancet window with curvilinear tracery that includes triskelions. Additional ornamentation in the form of naturalistic vegetation, gables, pinnacles, and delicate sculpture niches are further testaments of the talents of the masons' workshop.[34] Work on the façade stopped before it was completed; there is no evidence of the iron hooks that are needed to attach figural sculptures.[34]

At Lyon Cathedral, the Bourbons chapel, built during the last decades of the 15th century by the Cardinal Charles II, Duke of Bourbon and his brother Pierre de Bourbon, son-in-law of Louis XI, is a key example of the trend of expanding existing Gothic churches in the newer Flamboyant style.[35] Consisting of two bays, it features a small oratory and a sacristy. The pendant vaults are decorated with finely carved keystones. The mouldings of the transverse ribs are decorated with the monograms of Charles de Bourbon, Pierre de Bourbon, and his wife, Anne of France.

-

West façade, Abbey-church of Saint-Antoine, Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye (15th century)

-

Bourbons chapel, Lyon Cathedral, engraving by Ebenezer Challis after a drawing by Thomas Allom (19th century)

-

Pendant vaults and mouldings with monograms, Bourbons chapel, Lyon Cathedral (late 15th century)

The transition from Flamboyant Gothic to early French Renaissance began during the reign of Louis XII (1495) and lasted until roughly 1525 or 1530. During this brief transition period, the ogee arch and the naturalism of the Gothic style was blended with round arches, flexible forms, and stylized antique motifs that are typical of Renaissance architecture. A good deal of Gothic decoration is apparent at the Château de Blois but it is totally absent from the tomb of Louis XII, which is housed in the abbey-church of Saint-Denis.

In 1495, a colony of Italian artists was established in Amboise and worked in collaboration with French master masons. This date is generally considered to be the starting point of the period of interaction between the Flamboyant Gothic and early French Renaissance styles. In general, theories of building design and structure remained French while surface decoration became Italian. There were connections between French architectural production and other stylistic traditions, including Plateresque in Spain and the decorative arts of the north—especially Antwerp.[36]

The limits of this style, which is called style Louis XII in French, were variable, especially outside the Loire Valley. This period includes the seventeen-year reign of Louis XII (1498–1515), the end of the reign of Charles VIII, and the beginning of that of Francis I, whose rule corresponded with a definitive stylistic change. The creation of the School of Fontainebleau in 1530 by Francis I is generally considered the turning point of the acceptance and establishment of the Renaissance style in France.[37] Early evidence of the intermingling of Flamboyant and classicizing decorative motifs can be found at the Château de Meillant, which was transformed by Charles II d'Amboise, governor of Milan, in 1473. The structure remained fully medieval but the superposition of the windows in bays connected to each other by extended, cord-like pinnacles foreshadows the grid designs of the façades of early French Renaissance monuments. Other notable features include the entablature with classical egg-and-dart motifs surmounted by a Gothic balustrade and the treatment of the upper part of the helical staircase with a semi-circular arcade equipped with shells.[38] In the final years of the reign of Charles VIII, experimentation with Italian ornamentation continued to enrich and mix with the Flamboyant repertoire.[39] With the ascendancy of Louis XII, French masons and sculptors were further exposed to new, classicizing motifs that were popular in Italy.[39]

In architectural sculpture, the systematic contribution of Italian elements and the "Gothic" reinterpretation of Italian Renaissance works is evident in the Abbey of Saint-Pierre in Solesmes, where the Gothic structure takes the form of a Roman triumphal arch flanked by pilasters with Lombard candelabra. Gothic foliage, which was now more jagged and wilted as seen at the Hôtel de Cluny in Paris, mingles with portraits of Roman emperors in medallions at the Château de Gaillon.[40] The maison des Têtes (1528–1532) in Valence is another example of Flamboyant blind tracery and foliage mixing with classicizing figures, medallions, and portraits of Roman emperors.

In architecture, the use of brick and stone on buildings from the 16th century can be observed, for example in the Louis XII wing of the Château of Blois. The French high roofs with turrets in the corners and the façades with helical staircases perpetuated the Gothic tradition but the systematic superposition of the bays, the removal of the lucarnes, and the appearance of loggias influenced by the villa Poggio Reale and the Castel Nuovo of Naples are evidence of a new decorative art in which the structure remains deeply Gothic. The spread of ornamental vocabularies from Pavia and Milan also played major roles. Equally important is the influence of Italian architects who designed formal gardens and fountains to complement French monuments as seen at the Château de Blois (1499) and the Château de Gaillon shortly thereafter.

The incorporation of Flamboyant Gothic with the classicizing forms of Italy produced eclectic, hybrid structures that were rooted in traditional French building practices yet modernized through the application of imported antique motifs and surface decoration. These transitional monuments led to the birth of French Renaissance architecture.

-

Louis XII wing of the Château de Blois (1498–1503)

-

Fusion of Flamboyant Gothic and Renaissance exterior decoration at Château de Gaillon (1502–1510)

-

Burial of Christ, Solesmes Abbey (1496)

-

Chapel vault with classicizing decoration, church of Saint-Pierre, Caen, by Hector Sohier (1518–1545)

-

Southeast side of the church of Saint-Pierre, Caen, showing combinations of Flamboyant Gothic and antique forms

-

The Longueville staircase, Château de Châteaudun, showing juxtaposition of Flamboyant Gothic and antique decoration

-

Detail of the Longueville staircase, Château de Châteaudun, showing juxtaposition of Flamboyant Gothic and antique decoration

-

Maison des Têtes (1528–1532), Valence

-

Angers Cathedral, a Renaissance lantern atop the Flamboyant Gothic central tower (finished 1515)

-

Tours Cathedral (finished 1507) with Renaissance lanterns atop the flamboyant towers

Low Countries

[編集]Variations of Flamboyant, influenced by France but with their own characteristics, began to appear in other parts of continental Europe.[41] Flamboyant had a particularly strong influence in Low Countries, which was then part of the Spanish Netherlands and was also a part of the Catholic diocese of Cologne. Extraordinarily high towers were a feature of the Belgian style. In the 15th century, Belgian architects produced remarkable examples of religious and secular Flamboyant architecture, one of which is the tower of St. Rumbold's Cathedral in Mechelen (1452–1520), which was built as both a bell tower and a watch tower for the defence of the city. The tower was intended to be 167メートル (548 ft) high and was designed to have a 77-メートル-high (253 ft) spire, only 7メートル (23 ft) of which was completed. Other notable Flamboyant cathedrals include Antwerp Cathedral with a 123-メートル-high (404 ft) tower and an unusual dome on pendentives that is decorated with a Flamboyant rib vault; St. John's Cathedral ('s-Hertogenbosch) in 's-Hertogenbosch (1220–1530), the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula in Brussels (1485–1519); and Liege Cathedral.[41]

-

Tower of St Rumbold's Cathedral in Mechelen (1452–1520)

-

Lantern tower, Antwerp Cathedral, consecrated 1521

-

Cathedral of St Michael and St Gudula, Brussels (1485–1519)

-

Grote Kerk (Breda), Breda (1410–1547)

-

St. John's Cathedral ('s-Hertogenbosch), 's-Hertogenbosch (1220–1530)

The town halls of Belgium, many of which were built by the prosperous textile merchants of Flanders, were even more flamboyant. They were among the last great statements of Gothic style as the Renaissance gradually came to Northern Europe, and were designed to showcase the wealth and splendour of their cities. Major examples include the town hall of Leuven (1448–1469) with its multiple, almost fantastic towers,[41] and those of Brussels (1401–1455), Oudenaarde (1526–1536), Ghent (1519–1539), and Mons (1458–1477).[41]

-

Leuven's Town Hall (1448–1469)

-

Detail of the facade of Leuven's Town Hall

-

Brussels' Town Hall (1401–1455)

-

Oudenaarde's Town Hall (1526–1536)

Adaptations in Holland and of Zeeland

[編集]Many churches in the former Counties of Holland and of Zeeland are built in a style sometimes inaccurately separated as Hollandic and as Zeelandic Gothic. These are in fact Brabantine Gothic style buildings with concessions necessitated by local conditions. Thus (except for Dordrecht), because of the soggy ground, weight was saved by wooden barrel vaults instead of stone vaults and the flying buttresses required for those. In most cases, the walls were made of bricks but cut natural stone was not unusual.

Everaert Spoorwater played an important role in spreading Brabantine Gothic into Holland and Zeeland. He perfected a method by which the drawings for large constructions allowed ordering virtually all natural stone elements from quarries on later Belgian territory, then at the destination needing merely their cementing in place. This eliminated storage near the construction site, and the work could be done without the permanent presence of the architect.

-

Gouda's Town Hall

-

Middelburg's Town Hall

Spain

[編集]Before the unification of Spain, monuments were constructed in the Flamboyant style in the Crown of Aragon and Kingdom of Valencia, where Marc Safont was among the most important architects of the Late Middle Ages. Safont was commissioned to repair the Palau de la Generalitat de Catalunya in Barcelona and worked on this project from 1410 to 1425.[42] He designed the building's courtyard and elegant galleries.[43]en:Template:Page range too broad Also notable is the Chapel of Sant Jordi (1432–34), which has a striking façade consisting of an entry portal flanked by windows resplendent with blind and openwork Flamboyant tracery.[42] The chapel's interior includes a lierne vault with a keystone depicting Saint George and the Dragon.

Following the 1428 Catalonia earthquake, a replacement Flamboyant rose window on the west façade of the church of Santa Maria del Mar, Barcelona, was completed by 1459. Additional examples of the Flamboyant style include the cloister of the Convent of Sant Doménec in the Kingdom of Valencia.

Spain was united by the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile in 1469, and saw the conquest of Granada, the last stronghold of Moorish occupation, in 1492. This was followed by a great wave of construction of new cathedrals and churches in what became known as the Isabelline style after the queen. This late Spanish Gothic style includes a mixture of French-inspired Flamboyant tracery and vaulting features, Flemish features such as fringed arches, and elements that may have been borrowed from Islamic architecture, such as the crossed rib vaults and pierced openwork tracery of Burgos Cathedral.[44] To this, Spanish architects such as Juan Guas added distinctive new features, for example in the Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo (1488–1496) and the Colegio de San Gregorio (completed 1487).[45] The rose window on the west façade of Toledo Cathedral (late 15th century) is a good example.[46]

Juan de Colonia and his son Simón de Colonia, originally from Cologne, are other notable architects of the Isabelline style; they were the chief architects of the flamboyant features of Burgos Cathedral (1440–1481), including the openwork towers and the tracery in the star vault in the Chapel of the Constable.[45]

-

Façade of the Saint George chapel in the Generalitat Palace, Barcelona (1432–1434)

-

Vault of the Saint George chapel in the Generalitat Palace, Barcelona

-

Rose window, west façade, Basílica de Santa Maria del Mar, Barcelona (1459)

-

Cloister of the Convent of Sant Doménec, Valencia

-

Colegio de San Gregorio (Completed 1487)

-

Decoration of Colegio de San Gregorio (1488–1496)

-

Vaults of the lower cloister of the Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo (1477–1504)

-

Star vault in the Constable Chapel of Burgos Cathedral by Simón de Colonia

-

Rose window of west facade of Toledo Cathedral (end of 15th century)

Portugal

[編集]The Manueline style was named for King Manuel I of Portugal, who reigned from 1495 to 1523. The style was created to show Portugal was architecturally and politically independent of Spain.[要出典] Batalha Monastery's construction began in 1387 to celebrate John I of Portugal's victory over John I of Castile at the 1385 Battle of Aljubarrota, which secured the independence of the Kingdom of Portugal. Batalha was modified in the Flamboyant style after 1400. The building includes elements borrowed by the English Perpendicular style, tracery inspired by French Flamboyant, and German-inspired openwork steeples.[47]

In 1495, Portuguese navigators opened a sea-route to India and began trading with Brazil, Goa, and Malacca, bringing enormous wealth into Portugal. King Manuel funded a series of new monasteries and churches that were covered with decoration inspired by banana trees, sea shells, billowing sails, seaweed, barnacles, and other exotic elements as a monument to the Portuguese navigator Vasco de Gama and to celebrate Portugal's empire. The most lavish example of this decoration is found on the Convent of Christ in Tomar (1510–1514).[48]

-

Batalha Monastery (1386–1517)

-

Flamboyant window of Batalha Monastery (1386–1517)

-

Jeronimos Monastery, Belem (1501–158)

-

Marine themed decoration of the Chapter House window of the Convent of Christ (Tomar) (1510–1514)

Central Europe

[編集]Architects in central Europe adopted some forms and elements of Flamboyant in the late 14th century, and added many innovations of their own. The Late Gothic buildings of Austria, Bavaria, Saxony, and Bohemia are sometimes called Sondergotik. The high triple west porch of Ulm Minster was placed at the base of the tower; it was designed by Ulrich von Ensingen. The porch, which was in the centre of the facade—a break from earlier Gothic styles. Work on the tower was continued by Ensingen's son after 1419 and much more decoration was added from 1478 to 1492 by Matthaus Boblinger. The spire was added between 1881 and 1890, which made it the tallest tower in Europe.[49]

Other remarkable towers were constructed like openwork webs of stone; these include Johannes Hultz's additions to the tower of Freiburg Minster, which had an open spiral staircase and a lacework octagonal spire; the additions were begun in 1419.

-

West porch and tower of Ulm Minster (begun late 14th century, completed 19th)

-

Detail of the tower of Ulm Minster, 19th century.

-

Detail of the tower of Freiburg Minster

-

Looking up into the spire of Freiburg Minster (after 1419)

British Isles

[編集]Flamboyant had little influence in England, where the Perpendicular style prevailed.[41] Flamboyant architecture was not common in the British Isles but examples are numerous. The flame-like window tracery appeared at Gloucester Cathedral before it appeared in France.[50] In Scotland, Flamboyant detailing was employed in window tracery of the northern side of the nave at Melrose Abbey, and for the west window that completed the construction of Brechin Cathedral.[51] Melrose Abbey had been destroyed during the English invasion of 1358 and the initial rebuilding followed the traditions of English masons. From c.1400, the Parisian master-builder John Morow began work on the Abbey, leaving an inscription identifying him in the church's south transept.[51] Morow had possibly been brought to Great Britain by Archibald Douglas, 4th Earl of Douglas, for whom he also worked on Lincluden Collegiate Church.[52] The design of some windows in both Brechin and Melrose are so similar it is possible Morow or his team of Continental masons worked on both. Comparison can also be made with the chapel (1379 – ) of the Château de Vincennes, a castle and royal residence near Paris.[51] Somewhat later, further Flamboyant work was done on the western bays of Brechin Cathedral.[51]

In England, the contemporaneous Late Gothic (or Third Pointed) style Perpendicular Gothic was prevalent from the middle 14th century. A very early example of Flamboyant tracery is found in the top of the Great West Window in York Minster—the cathedral of the Archbishop of York. It also appears in the Flamboyant curvilinear bar-tracery of St Matthew's Church at Salford Priors, Warwickshire.[1][53]

Characteristics

[編集]Tracery

[編集]The flamboyant tracery designs are the most characteristic feature of the Flamboyant style.[54] They appeared in the stone mullions, the framework of windows, particularly in the great rose windows of the period, and in complex, pointed, blind arcades and arched gables that were stacked atop one another, and which often covered the entire façade. They were also used in balustrades and other features.[55] Interlocking openwork gables and balustrades, as seen on the west porch of the church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen, were often used to disguise or diffuse the mass of buildings.

An important early example from the late 15th century is the west rose window of the royal chapel, Sainte-Chapelle (1485–98), depicting the Apocalypse of St John. It is 9 meters (29.5 feet) in diameter, with eighty-nine panels arranged in three concentric zones around a central eye.[56] Flamboyant rose windows are also prominent features of the transept of Sens Cathedral (15th c.) and the transept of Beauvais Cathedral (1499), one of the few parts of that Cathedral still standing. The Flamboyant facades of Sens Cathedral, Beauvais Cathedral, Senlis Cathedral and Troyes Cathedral (1502–1531) were all the work of the same master builder, Martin Chambiges.[57][58]

Flamboyant windows were often composed of two arched windows, over which was a pointed, oval design divided by curving lines called soufflets and mouchettes. Examples are found in the Church of Saint-Pierre, Caen.[59] Mouchettes and soufflets were also applied in openwork form to gables, as seen on the west façade of Trinity Abbey, Vendôme.

-

West rose window of Saint Chapelle (1485–1498)

-

Flamboyant window tracery, Limoges Cathedral (late 15th century)

-

Openwork gable and balustrade, west porch, church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen (1435–1521)

-

Mouchettes in the south façade windows of the Church of Saint-Pierre, Caen

-

A soufflet from a window on the south façade of the Church of Saint-Pierre, Caen

-

West façade of Trinity Abbey, Vendôme

-

Flamboyant rose window and façade, south transept Sens Cathedral (late 15th–early 16th century)

-

North rose window, Beauvais Cathedral (1540–1548)

Façades and porches

[編集]The term "Flamboyant" typically refers to church façades and to some secular buildings such as the Palais de Justice in Rouen.[21] Church façades and porches were often the most elaborate architectural features of towns and cities, especially in France, and frequently projected outwards onto marketplaces and town squares.[60] The intricate and dazzling forms of many façades and porches often appealed to their urban contexts; in some cases, new façades and porches were designed to create impressive architectural vistas when viewed from a specific street or square.[61] This architectural response to increasing concerns with the aesthetics of urban space is particularly notable in Normandy, where a striking group of late 15th- and early 16th-century projecting polygonal porches were constructed in the Flamboyant style; examples include Notre-Dame, Alençon; La Trinité, Falaise; Notre-Dame, Louviers; and Saint-Maclou, Rouen.[23]

Martin Chambiges, the most prolific French architect between c. 1480 and c. 1530, combined three-dimensional forms such as nodding ogees with a miniaturized vocabulary of niches, baldachins, and pinnacles to produce dynamic façades with a new sense of depth at Sens Cathedral, Beauvais Cathedral, and Troyes Cathedral.[23] The addition of sumptuous Flamboyant façades and porches provided new public faces to older monuments that survived the Hundred Years' War.[62] Façades and porches often used the arc en accolade, an arched doorway that was topped by short pinnacle with a fleuron or carved stone flower, often resembling a lily. The short pinnacle bearing the fleuron had its own decoration of small, sculpted forms like twisting leaves of cabbage or other naturalistic vegetation. There were also two slender pinnacles, one on either side of the arch.[3]

-

West porch, Notre-Dame d'Alençon

-

West porch, La Trinité, Falaise

-

West porch, church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen

-

South transept façade, Beauvais Cathedral

-

North transept façade, Sens Cathedral

-

West façade, Troyes Cathedral

-

Parlement de Normandie, Rouen, now the Palais de justice

Vaults, piers, and mouldings

[編集]Elision—the elimination of capitals—coupled with the introduction of continuous and "dying" mouldings, are additional noteworthy characteristics of which the parish church of Saint-Maclou in Rouen is a key example.[23] The uninterrupted fluidity and merging of disparate forms led to the emergence of decorative Gothic vaults in France.[23]

Another characteristic feature were vaults with additional types of ribs called the lierne and the tierceron, whose functions were purely decorative. These ribs spread out over the surface to make a star vault; a ceiling of star vaults gave the ceiling a dense network of decoration.[63] Another feature of the period was a type of very tall, round pillar without a capital, from which ribs sprang and spread upwards to the vaults. They were often used as the support for a fan vault, which branched upward like a spreading tree. A fine example is found in the chapel of the Hotel de Cluny in Paris (1485–1510).[55][3]

-

Vaults of the chapel of the Hotel de Cluny (1485–1510)

-

Nave of the church of Saint-Maclou, Rouen Note the absence of capitals and use of continuous mouldings throughout.

-

Transept pier and vaults, Basilica of Saint-Nicolas-de-Port

-

Chapelle du Saint-Esprit, Rue

Notable Flamboyant religious buildings in France

[編集]- Auch (Gers), Auch Cathedral (except the façade)

- Beauvais (Oise), transept façades of Beauvais Cathedral

- Beauvais (Oise), choir and chapels of the Church of Saint-Étienne de Beauvais

- Bourg-en-Bresse (Ain), Royal Monastery of Brou

- Caudebec-en-Caux (Seine-Maritime), Church of Notre-Dame

- L'Épine (Marne), Notre-Dame de l'Épine

- Évreux (Eure), north transept of Évreux Cathedral

- Louviers (Eure), Notre-Dame de Louviers (north and south façade)

- Nantes (Loire-Atlantique), Nantes Cathedral

- Paris, Church of Saint-Séverin

- Paris, Saint-Jacques Tower, bell tower of the former church of Saint-Jacques de la Boucherie

- Pont-de-l'Arche (Eure), Notre-Dame-des-Arts

- Rouen (Seine-Maritime), Rouen Cathedral (in part)

- Rouen (Seine-Maritime), Church of Saint-Maclou

- Rouen (Seine-Maritime), abbey-church of Saint-Ouen

- Rue (Somme), Chapel of Saint-Esprit

- Saint-Nicolas-de-Port (Meurthe-et-Moselle), Basilica of Saint-Nicolas

- Saint-Riquier (Somme), Abbey

- Senlis (Oise), transepts of Senlis Cathedral

- Sens (Yonne), Sens Cathedral (south transept)

- Thann (Haut-Rhin), St Theobald's Church

- Toul (Meurthe-et-Moselle), west façade of Toul Cathedral

- Tours (Indre-et-Loir), Tours Cathedral (west façade)

- Vendôme (Loir-et-Cher), west façade of the Abbaye de la Trinité

- Vincennes (Val-de-Marne), Sainte-Chapelle

Notable examples of civil architecture in France

[編集]- Beaune (Côte-d'Or), hospices

- Beauvais (Oise), former episcopal palace

- Bourges (Cher), Palais Jacques Cœur

- Château de Châteaudun (Eure-et-Loir)

- Paris, Hôtel de Cluny

- Paris, Hôtel de Sens

- Rouen (Seine-Maritime), Palais de Justice

Examples of the Flamboyant Gothic Style outside France

[編集]- St. Lorenz, Nuremberg (nave ceiling in particular), Germany

- Milan Cathedral, a relatively rare Italian building in the style, which is adopted very fully here

- Vladislav Hall in Prague Castle (vaults), Czech Republic

- Seville Cathedral, Spain

- Capella de Sant Jordi, Palau de la Generalitat de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

- Batalha Monastery, Portugal

- Brussels Town Hall, Belgium

- Church of St. Anne, Vilnius, Lithuania

画像

[編集]-

St Anne's, Vilnius, Lithuania (1500)

-

St. Vulfran Collegiate Church, west façade, Abbeville

-

Church of Saint-Étienne, interior, chevet, Beauvais

-

Notre-Dame de l'Épine, west façade, L'Épine

-

Évreux Cathedral, north transept façade, Évreux

-

Abbey-church of St. Ouen, nave elevation, Rouen

-

Chapel of Saint-Esprit, Rue

-

West façade of Tours Cathedral (towers completed 1547)

関連項目

[編集]- French Gothic architecture

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- International Gothic

- Rayonnant

- High Gothic

Footnotes

[編集]- ^ The church was demolished in 1797 following the French Revolution. See Mérimée database

- ^ Content in this section is translated from the existing French Wikipedia article; see its history for attribution.

Citations

[編集]- ^ a b c d e Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan, eds. (2015), “Flamboyant” (英語), A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5 2020年6月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Watkin 1986, p. 139.

- ^ a b c Renault & Lazé 2006, p. 37.

- ^ Wilson 1990, p. 252.

- ^ a b c d Neagley, Linda Elaine (2007). “Maestre Carlín and 'Proto' Flamboyant Architecture of Rouen (c. 1380-1430)”. In Jiménez, Alfonso Martin. La Piedra Postrera (Simposio Internacional sobre la catedral de Sevilla en el contexto del gótico final). Seville. p. 47–60

- ^ Ackerman 1949, p. 84–111.

- ^ Kavaler 2012, p. 259–260.

- ^ Adamski 2019, p. 183–205.

- ^ “Flamboyant style | Gothic architecture” (英語). Encyclopedia Britannica. 2020年6月28日閲覧。

- ^ Schurr, Marc Carel (2010), Bork, Robert E., ed., “art and architecture: Gothic” (英語), The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662624.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-866262-4 2020年4月9日閲覧。

- ^ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan, eds. (2015), “Gothic” (英語), A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5 2020年4月9日閲覧。

- ^ Lafond, Jean (1973). “Le peintre-graveur E.-Hyacinthe Langlois, "parrain " du style gothique flamboyant”. Bulletin de la Société nationale des Antiquaires de France 1971 (1): 313–317. doi:10.3406/bsnaf.1973.8078.

- ^ Hart 2012, p. 1-4.

- ^ Benton 2002, p. 151-152.

- ^ Benton 2002, p. 191.

- ^ a b c Stokstad, Marilyn (2019). Medieval Art (Second ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 345. ISBN 9780367319373. OCLC 1112381140

- ^ Wilson 1990, p. 248.

- ^ a b c Bork 2018, p. 96.

- ^ a b Wilson 1990, p. 249.

- ^ Fletcher, Banister, Sir (1996). Sir Banister Fletcher's a history of architecture.. Cruickshank, Dan. (20th ed.). Oxford: Architectural Press. pp. 444. ISBN 0-7506-2267-9. OCLC 35249531

- ^ a b Kavaler 2012, p. 115.

- ^ “Chapels 24 | Life of a Cathedral: Notre-Dame of Amiens”. projects.mcah.columbia.edu. 2020年6月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e Kidson, Peter; Davis, Michael T.; Crossley, Paul; Sandron, Dany; Morrison, Kathryn; Bräm, Andreas; Blum, Pamela Z.; Sekules, V.; Lindley, Phillip; Henze, Ulrich; Holladay, Joan A.; Kreytenberg, G.; Tigler, Guido; Grandi, R.; d'Achille, Anna Maria; Aceto, Francesco; Steyaert, J.; Dias, Pedro; Svanberg, Jan; Mata, Angela Franco; Evelyn, Peta; Tångeberg, Peter; Hicks, Carola; Campbell, Marian; Taburet-Delahaye, Elisabeth; Koldeweij, A. M.; Reinheckel, G.; Kolba, Judit; Karlsson, Lennart; et al. (2003). Gothic. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t033435. ISBN 9781884446054。

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=は無視されます。 (説明)( 要購読契約)

要購読契約)

- ^ a b Watkin 1986, p. 142.

- ^ CMN. “Qui était Jean de Dunois ? - CMN” (フランス語). www.chateau-chateaudun.fr. 2024年3月21日閲覧。

- ^ “Palais de justice”. www.pop.culture.gouv.fr. 2020年6月23日閲覧。

- ^ Neagley 1998, p. 47-54.

- ^ Neagley 1988, p. 376.

- ^ Kavaler 2012, p. 7–8.

- ^ de Finance 2012, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Meunier 2014, p. 48-49.

- ^ Lours 2018, p. 412.

- ^ Mocellin 2019, p. 122.

- ^ a b Mocellin 2019, p. 70–78.

- ^ Monfalcon, Jean Baptiste (1866) (フランス語). Histoire monumentale de la ville de Lyon. A la Bibliothèque de la Ville. pp. 383–384

- ^ Wolff, Martha (2011). Kings, queens, and courtiers art in early Renaissance France : [exhibition, "France 1500: entre Moyen Age et Renaissance", Galeries nationales, Grand Palais, Paris, October 6, 2010 - January 10, 2011; "Kings, queens, and courtiers: art in early Renaissance France", Art institute of Chicago, February 27 - May 30, 2011]. Art Institute of Chicago. p. 32. ISBN 978030017025-2. OCLC 800990733

- ^ Babelon 1989, p. 195-196.

- ^ Pérouse de Montclos, Jean-Marie (1992). Guide du patrimoine Centre Val de Loire. Paris: Hachette. p. 436–439. ISBN 2-01-018538-2. OCLC 489587981

- ^ a b Bork 2018, p. 237–238.

- ^ Caron 2017, p. 75–76.

- ^ a b c d e Watkin 1986, p. 166.

- ^ a b Hughes 1993, p. 120.

- ^ Buades 2008, p. 97–148.

- ^ Watkin 1986, p. 174-75.

- ^ a b Watkin 1986, p. 174-175.

- ^ Brisac 1994, p. 110.

- ^ Watkin 1986, p. 176.

- ^ Watkin 1986, p. 177.

- ^ Watkin 1986, p. 162-3.

- ^ Ducher 2014, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d “Corpus of Scottish medieval parish churches: Brechin Cathedral”. arts.st-andrews.ac.uk. St Andrews University. 2020年6月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Corpus of Scottish medieval parish churches: Roslin Collegiate Church”. arts.st-andrews.ac.uk. St Andrews University. 2020年6月28日閲覧。

- ^ Curl, James Stevens (2015), Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan, eds., “tracery” (英語), A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Oxford University Press), doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5 2020年6月28日閲覧。

- ^ Białostocki 1966, p. 94.

- ^ a b Ducher 2014, p. 52.

- ^ de Finance 2012, p. 62.

- ^ “Sens”. Grove Art Online/Oxford Art Online.. Oxford University Press. May 7, 2015閲覧。

- ^ Harvey, John (1950). The Gothic World. Batsford

- ^ Ducher 2014, p. 52-3.

- ^ Kavaler 2012, p. 116.

- ^ Neagley 2008, p. 44–50.

- ^ Kavaler 2012, p. 122.

- ^ Ducher 2014, p. 52-53.

参考文献

[編集]- Ackerman, James S. (1949). “'Ars Sine Scientia Nihil Est' Gothic Theory of Architecture at the Cathedral of Milan”. The Art Bulletin 31 (2): 84–111. doi:10.2307/3047224. JSTOR 3047224.

- Adamski, Jakub (2019). “The von der Heyde Chapel at Legnica in Silesia and the Early Phase of the French Flamboyant Style”. Gesta 58 (2): 183–205. doi:10.1086/704253.

- Babelon, Jean Pierre (1989). Châteaux de France au siècle de la Renaissance. Paris: Flammarion/Picard. ISBN 208012062X

- Bechmann, Roland (2017) (フランス語). Les Racines des Cathédrales. Payot. ISBN 978-2-228-90651-7

- Beltrami, Costanza (2016). Building a crossing tower: a design for Rouen Cathedral of 1516. London: Paul Holberton Publishing. ISBN 9781907372933

- Benton, Janetta (2002). Art of the Middle Ages. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500203507

- Białostocki, Jan (1966). “Late Gothic: Disagreements About the Concept”. Journal of the British Archaeological Association 29 (1): 76–105. doi:10.1080/00681288.1966.11894934.

- Bork, Robert (2018). Late Gothic Architecture: Its Evolution, Extinction, and Reception. Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN 9782503568942

- Bos, Agnès (2003). Les églises flamboyantes de Paris: XVe-XVIe siècles. Paris: Picard. ISBN 9782708407022

- Bottineau-Fuchs, Yves (2001). Haute-Normandie Gothique: Architecture Religieuse. Paris: Picard. ISBN 9782708406179

- Brisac, Catherine (1994) (フランス語). Le Vitrail. Paris: La Martinière. ISBN 2-73-242117-0

- Buades, Marià Carbonell i (2008). “De Marc Safont a Antoni Carbonell: la pervivencia de la arquitectura gótica en Cataluña” (スペイン語). Artigrama 23: 97–148.

- Caron, Sophie (2017). “De la Toscane à la Normandie: Les ateliers de sculpteurs sur le chantier de Gaillon”. In Calame-Levert, Florence; Hermant, Maxence; Toscano, Gennaro. Une Renaissance en Normandie: le cardinal Georges d'Amboise bibliophile et mécène: [ouvrage publié à l'occasion de l'exposition présentée au Musée d'art, histoire et archéologie d'Evreux du 8 juillet au 22 octobre 2017]. Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo. pp. 70–76. ISBN 9782353402618

- Davis, Michael T. (1983). “'Troys Portaulx et Deux Grosses Tours': The Flamboyant Façade Project for the Cathedral of Clermont”. Gesta 22 (1): 67–83. doi:10.2307/766953. JSTOR 766953.

- Ducher, Robert (2014) (フランス語). Caractéristique des Styles. Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-0813-4383-2

- Emery, Anthony (2015). Seats of Power in Europe During the Hundred Years War: an architectural study from 1330 to 1480. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781785701030. OCLC 928751448

- de Finance, Laurence (2012) (French). La Sainte-Chapelle- Palais de la Cité. Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux. ISBN 978-2-7577-0246-8

- Guillouët, Jean-Marie (2019). Flamboyant architecture and medieval technicality (c. 1400-c. 1530): a micro-history of the rise of artistic consciousness at the end of Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN 9782503577296

- Hamon, Étienne (2011). Une capitale flamboyante: la création monumentale à Paris autour de 1500. Paris: Picard. ISBN 9782708409095

- Hart, Stephen (2012). Medieval church window tracery in England. Woodbridge; Rochester: The Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843835332

- Hughes, Robert (1993). Barcelona. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 9780307764614. OCLC 774576886

- Lours, Mathieu (2018) (フランス語). Dictionnaire des Cathédrales. Éditions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-2755-807653

- Kavaler, Ethan Matt (2012). Renaissance Gothic: Architecture and the Arts in Northern Europe, 1470-1540. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300167924

- Mignon, Olivier (2017) (フランス語). Architecture du Patrimoine Française - Abbayes, Églises, Cathédrales et Châteaux. Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-27373-7611-5

- Meunier, Florian (2014). Le Paris du Moyen Âge. Editions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-27373-6217-0

- en:Template:long dash (2015). Martin & Pierre Chambiges: architectes des cathédrales flamboyantes. Paris: Picard. ISBN 9782708409750

- Mocellin, Géraldine, ed (2019). Saint-Antoine l'abbaye: un millénaire d'histoire. Grenoble: Glénat. ISBN 9782344035405

- Neagley, Linda Elaine (1988). “The Flamboyant Architecture of St.-Maclou, Rouen, and the Development of a Style”. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 47 (4): 374–396. doi:10.2307/990382. JSTOR 990382.

- en:Template:long dash (1998). Disciplined Exuberance: The Parish Church of Saint-Maclou and Late Gothic Architecture in Rouen. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271017167. OCLC 36103607

- en:Template:long dash (2008). “Late Gothic Architecture and Vision: Re-presentation, Sceneography and Illusionism”. In Reeve, Matthew M.. Reading Gothic Architecture. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 37–56. ISBN 9782503525365

- Pérouse de Montclos, Jean-Marie (1992). Centre: Val de Loire. Paris: Hachette. ISBN 9782010185380

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2006) (フランス語). Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier. Gisserot. ISBN 9-782877-474658

- Reveyron, Nicolas; Tuloup, Jean-Sébastien, eds (n.d.). Primatial Church of Saint-John-the-Baptist, Cathedral of Lyon. Lyon: Impr. Beau'Lieu. OCLC 943383702

- Sanfaçon, Roland (1971). L'architecture Flamboyante en France. Quebec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval. OCLC 1015901639

- Texier, Simon (2012). Paris Panorama de l'architecture de l'Antiquité à nos jours. Paris: Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3

- Wenzler, Claude (2018), Cathédrales Gothiques - un Défi Médiéval, Éditions Ouest-France, Rennes (in French) ISBN 978-2-7373-7712-9

- Wilson, Christopher (1990). The Gothic Cathedral: the architecture of the great church. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500341056

[[:en:Template:Gothic architecture]]<!-- {{Gothic architecture}} -->

[[Category:ゴシック建築]]

[[Category:フランスのゴシック建築]]

[[Category:ポルトガルのゴシック建築]]

[[Category:スペインのゴシック建築| ]]

[[en:Flamboyant]]

<!-- Wikipedia 翻訳支援ツール Ver1.32、[[:en:Flamboyant]](2022年10月7日 12:23:54(UTC))より -->