利用者:ShuBraque/sandbox/比較静学

経済学において、比較静学(英: comparative statics)とは、ある経済の外生的パラメータを変化させ、その経済の外生的パラメータの変化前と変化後の二つの異なる結果を比較するものである[1]。

静学の研究では、(もし調整過程が存在するのなら)調整過程後の、二つの異なる均衡状態を比較する。静学においては均衡へ向かう「動き(motion)」や変化そのものの過程は考慮されない。

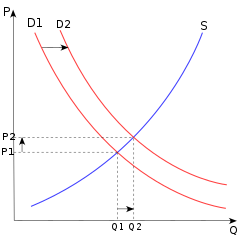

基本的には比較静学はある一つの市場における需要と供給の変化の研究や、金融政策や財政政策の変化がマクロ経済全体に及ぼす影響を調べる研究に使われている。「比較静学」という言葉そのものは、通常、マクロ経済学よりもミクロ経済学(一般均衡分析を含む)との関連で使用される。比較静学という言葉はジョン・ヒックス(1939)とポール・サミュエルソン(1947) (Kehoe, 1987, p. 517)によって形式化されたが、比較静学という概念は少なくとも1870年代には図を用いた形で提示されていた[2]。新古典派の成長モデル(en:neoclassical growth model)のような静的均衡モデルに対して、比較動学は比較静学に対応するものである(Eatwell, 1987)。

線形近似

[編集]比較静学による結果は、通常、en:implicit function theoremを用いて、均衡が静的であるとの仮定の下、均衡を定義する等式系の線形近似を計算することで導出される。これはすなわち、もし十分に小さな外生的パラメータの変化を考えるならば、それぞれの外生変数がどのように変化するのかを均衡の等式に出現する項の微分のみを用いて計算することができる。

例えば、ある外生変数の均衡値が次の等式で決定されるとする。

ここでは外生パラメータ。そして、一次近似に際して、の小さな変化に起因するの変化は次の条件を満たさなくてはいけない。

ここではの変化を表し、の変化はの変化を表している。また、とは、の、それぞれとに関する偏導関数(ただし、との初期値で評価されたもの)。これと等価的に、 の変化を次のように書くことができる。

この等式をdaで 割ることで x の a に関するComparative static derivative(比較的で静的な導関数)を得る。これは a の x 上の乗数とも呼ばれる。

複数の等式と複数の未知数

[編集]上記のすべての等式は個の未知数の個の等式の系である場合、真であり続ける。言い換えれば、は「個の未知数のベクトル」および「個の所与のパラメータのベクトル」を含む個の等式の系を示すということである。

もしパラメータが十分に小さな変化をするのであれば、その結果としての内生変数の変化をとして任意によく近似することができる。 このとき、 は変数に関する関数の×偏導関数の行列を表しており、は関数のパラメータに関する偏導関数の×行列を表している(との導関数はとの初期値で評価されたもの)。

ひとつの外生変数のひとつの内生変数に対する比較静学的な効果だけを求めるのであれば、en:全微分された等式系に対してクラメルの公式が使用可能な点に注意。

Stability

[編集]The assumption that the equilibrium is stable matters for two reasons. First, if the equilibrium were unstable, a small parameter change might cause a large jump in the value of , invalidating the use of a linear approximation. Moreover, Paul A. Samuelson's correspondence principle[3][4][5]:pp.122-123. states that stability of equilibrium has qualitative implications about the comparative static effects. In other words, knowing that the equilibrium is stable may help us predict whether each of the coefficients in the vector is positive or negative. Specifically, one of the n necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for stability is that the determinant of the n×n matrix B have a particular sign; since this determinant appears as the denominator in the expression for , the sign of the determinant influences the signs of all the elements of the vector of comparative static effects.

An example of the role of the stability assumption

[編集]Suppose that the quantities demanded and supplied of a product are determined by the following equations:

where is the quantity demanded, is the quantity supplied, P is the price, a and c are intercept parameters determined by exogenous influences on demand and supply respectively, b < 0 is the reciprocal of the slope of the demand curve, and g is the reciprocal of the slope of the supply curve; g > 0 if the supply curve is upward sloped, g = 0 if the supply curve is vertical, and g < 0 if the supply curve is backward-bending. If we equate quantity supplied with quantity demanded to find the equilibrium price , we find that

This means that the equilibrium price depends positively on the demand intercept if g – b > 0, but depends negatively on it if g – b < 0. Which of these possibilities is relevant? In fact, starting from an initial static equilibrium and then changing a, the new equilibrium is relevant only if the market actually goes to that new equilibrium. Suppose that price adjustments in the market occur according to

where > 0 is the speed of adjustment parameter and is the time derivative of the price — that is, it denotes how fast and in what direction the price changes. By stability theory, P will converge to its equilibrium value if and only if the derivative is negative. This derivative is given by

This is negative if and only if g – b > 0, in which case the demand intercept parameter a positively influences the price. So we can say that while the direction of effect of the demand intercept on the equilibrium price is ambiguous when all we know is that the reciprocal of the supply curve's slope, g, is negative, in the only relevant case (in which the price actually goes to its new equilibrium value) an increase in the demand intercept increases the price. Note that this case, with g – b > 0, is the case in which the supply curve, if negatively sloped, is steeper than the demand curve.

Comparative statics without constraints

[編集]Suppose is a smooth and strictly concave objective function where x is a vector of n endogenous variables and q is a vector of m exogenous parameters. Consider the unconstrained optimization problem . Let , the n by n matrix of first partial derivatives of with respect to its first n arguments x1,...,xn. The maximizer is defined by the n×1 first order condition .

Comparative statics asks how this maximizer changes in response to changes in the m parameters. The aim is to find .

The strict concavity of the objective function implies that the Jacobian of f, which is exactly the matrix of second partial derivatives of p with respect to the endogenous variables, is nonsingular (has an inverse). By the implicit function theorem, then, may be viewed locally as a continuously differentiable function, and the local response of to small changes in q is given by

Applying the chain rule and first order condition,

(See Envelope theorem).

Application for profit maximization

[編集]Suppose a firm produces n goods in quantities . The firm's profit is a function p of and of m exogenous parameters which may represent, for instance, various tax rates. Provided the profit function satisfies the smoothness and concavity requirements, the comparative statics method above describes the changes in the firm's profit due to small changes in the tax rates.

Comparative statics with constraints

[編集]A generalization of the above method allows the optimization problem to include a set of constraints. This leads to the general envelope theorem. Applications include determining changes in Marshallian demand in response to changes in price or wage.

Limitations and extensions

[編集]One limitation of comparative statics using the implicit function theorem is that results are valid only in a (potentially very small) neighborhood of the optimum—that is, only for very small changes in the exogenous variables. Another limitation is the potentially overly restrictive nature of the assumptions conventionally used to justify comparative statics procedures.

Paul Milgrom and Chris Shannon[6] pointed out in 1994 that the assumptions conventionally used to justify the use of comparative statics on optimization problems are not actually necessary—specifically, the assumptions of convexity of preferred sets or constraint sets, smoothness of their boundaries, first and second derivative conditions, and linearity of budget sets or objective functions. In fact, sometimes a problem meeting these conditions can be monotonically transformed to give a problem with identical comparative statics but violating some or all of these conditions; hence these conditions are not necessary to justify the comparative statics. Stemming from the article by Milgrom and Shannon as well as the results obtained by Veinott[7] and Topkis[8] an important strand of operational research was developed called Monotone Comparative Statics. In particular, this theory concentrates on the comparative statics analysis using only conditions that are independent of order-preserving transformations. The method uses lattice theory and introduces the notions of quasi-supermodularity and the single-crossing condition. The wide application of Monotone Comparative Statics to economics include: production theory, consumer theory, game theory with complete and incomplete information, auction theory, and others.[9]

See also

[編集]Notes

[編集]- ^ (Mas-Colell, Whinston, and Green, 1995, p. 24; Silberberg and Suen, 2000)

- ^ Fleeming Jenkin (1870), "The Graphical Representation of the Laws of Supply and Demand, and their Application to Labour," in Alexander Grant, Recess Studies and (1872), "On the principles which regulate the incidence of taxes," Proceedings of Royal Society of Edinburgh 1871-2, pp. 618-30., also in Papers, Literary, Scientific, &c, v. 2 (1887), ed. S.C. Colvin and J.A. Ewing via scroll to chapter links.

- ^ Samuelson, Paul, "The stability of equilibrium: Comparative statics and dynamics", Econometrica 9, April 1941, 97-120: introduces the concept of the correspondence principle.

- ^ Samuelson, Paul, "The stability of equilibrium: Linear and non-linear systems", Econometrica 10(1), January 1942, 1-25: coins the term "correspondence principle".

- ^ Baumol, William J., Economic Dynamics, Macmillan Co., 3rd edition, 1970.

- ^ Milgrom, Paul, and Shannon, Chris. "Monotone Comparative Statics" (1994). Econometrica, Vol. 62 Issue 1, pp. 157-180.

- ^ Veinott (1992): Lattice programming: qualitative optimization and equilibria. MS Stanford.

- ^ See: Topkis, D. M. (1979): “Equilibrium Points in Nonzero-Sum n-Person Submodular Games,” SIAM Journal of Control and Optimization, 17, 773–787; as well as Topkis, D. M. (1998): Supermodularity and Complementarity, Frontiers of economic research, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691032443.

- ^ See: Topkis, D. M. (1998): Supermodularity and Complementarity, Frontiers of economic research, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691032443; and Vives, X. (2001): Oligopoly Pricing: Old Ideas and New Tools. MIT Press, ISBN 9780262720403.

References

[編集]- John Eatwell et al., ed. (1987). "Comparative dynamics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 1, p. 517.

- John R. Hicks (1939). Value and Capital.

- Timothy J. Kehoe, 1987. "Comparative statics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 1, pp. 517–20.

- Andreu Mas-Colell, Michael D. Whinston, and Jerry R. Green, 1995. Microeconomic Theory.

- Paul A. Samuelson (1947). Foundations of Economic Analysis.

- Eugene Silberberg and Wing Suen, 2000. The Structure of Economics: A Mathematical Analysis, 3rd edition.

![{\displaystyle D_{q}x^{*}(q)=-[D_{x}f(x^{*}(q);q)]^{-1}D_{q}f(x^{*}(q);q).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e89de8f875adb74f0fc6993538f4a093db09d6f4)