「法人類学」の版間の差分

m →フォレンジック・タフォノミー (仮訳:法化石学): 写真の説明文を修正更新 |

|||

| 43行目: | 43行目: | ||

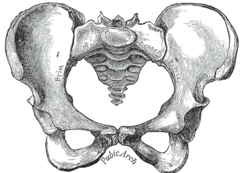

性別は、骨の性別的な固有の違いを探すことによって決定される。中でも[[骨盤]]は、性別の決定に極めて有用であり、もし入手可能であれば、非常に高いレベルの精度で決定することができる<ref name="Ident of Skel Remains"><cite class="citation web">[https://forensicmd.files.wordpress.com/2010/11/identification-of-skeletal-remains.pdf "Identification Of Skeletal Remains"] <span class="cs1-format">(PDF)</span>. forensicjournals.com. November 5, 2010<span class="reference-accessdate">. Retrieved <span class="nowrap">August 19,</span> 2015</span>.</cite><templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles></ref>。 {{multiple image|align=left|caption_align=center|total_width=500|image1=Gray242.png|caption1=女性の骨盤:幅が広く仙骨が短く奥にある|width1=250|height1=210|image2=Gray241.png|caption2=男性の骨盤: 幅が狭く仙骨が長い|width2=250|height2=210}} しかしながら、骨盤は常に存在するわけではないので、法人類学者は、性別間で明確な特徴を有する頭蓋骨といった、他の骨格上の違いも知っておく必要がある<ref name="juniordentist"><cite class="citation web">[http://www.juniordentist.com/differentiate-male-skull-female-skull.html "Differences Between Male Skull and Female Skull"]. ''juniordentist.com''. September 24, 2008<span class="reference-accessdate">. Retrieved <span class="nowrap">August 19,</span> 2015</span>.</cite><templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles></ref> <ref name="Smithsonian"><cite class="citation web">[http://anthropology.si.edu/writteninbone/male_female.html "Male or Female"]. ''Smithsonian National Museum of National History''<span class="reference-accessdate">. Retrieved <span class="nowrap">August 19,</span> 2015</span>.</cite><templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles></ref>。 |

性別は、骨の性別的な固有の違いを探すことによって決定される。中でも[[骨盤]]は、性別の決定に極めて有用であり、もし入手可能であれば、非常に高いレベルの精度で決定することができる<ref name="Ident of Skel Remains"><cite class="citation web">[https://forensicmd.files.wordpress.com/2010/11/identification-of-skeletal-remains.pdf "Identification Of Skeletal Remains"] <span class="cs1-format">(PDF)</span>. forensicjournals.com. November 5, 2010<span class="reference-accessdate">. Retrieved <span class="nowrap">August 19,</span> 2015</span>.</cite><templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles></ref>。 {{multiple image|align=left|caption_align=center|total_width=500|image1=Gray242.png|caption1=女性の骨盤:幅が広く仙骨が短く奥にある|width1=250|height1=210|image2=Gray241.png|caption2=男性の骨盤: 幅が狭く仙骨が長い|width2=250|height2=210}} しかしながら、骨盤は常に存在するわけではないので、法人類学者は、性別間で明確な特徴を有する頭蓋骨といった、他の骨格上の違いも知っておく必要がある<ref name="juniordentist"><cite class="citation web">[http://www.juniordentist.com/differentiate-male-skull-female-skull.html "Differences Between Male Skull and Female Skull"]. ''juniordentist.com''. September 24, 2008<span class="reference-accessdate">. Retrieved <span class="nowrap">August 19,</span> 2015</span>.</cite><templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles></ref> <ref name="Smithsonian"><cite class="citation web">[http://anthropology.si.edu/writteninbone/male_female.html "Male or Female"]. ''Smithsonian National Museum of National History''<span class="reference-accessdate">. Retrieved <span class="nowrap">August 19,</span> 2015</span>.</cite><templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles></ref>。 |

||

<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Cardoso|first=Hugo F.V.|date=January 2008|title=Sample-specific (universal) metric approaches for determining the sex of immature human skeletal remains using permanent tooth dimensions|url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0305440307000544|journal=Journal of Archaeological Science|volume=35|issue=1|pages=158–168| |

<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Cardoso|first=Hugo F.V.|date=January 2008|title=Sample-specific (universal) metric approaches for determining the sex of immature human skeletal remains using permanent tooth dimensions|url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0305440307000544|journal=Journal of Archaeological Science|volume=35|issue=1|pages=158–168|doi=10.1016/j.jas.2007.02.013}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Harris|first=Edward F.|last2=Lease|first2=Loren R.|date=November 2005|title=Mesiodistal tooth crown dimensions of the primary dentition: A worldwide survey|url=http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ajpa.20162|journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology|volume=128|issue=3|pages=593–607|doi=10.1002/ajpa.20162|issn=0002-9483}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Paknahad|first=Maryam|last2=Vossoughi|first2=Mehrdad|last3=Ahmadi Zeydabadi|first3=Fatemeh|date=November 2016|title=A radio-odontometric analysis of sexual dimorphism in deciduous dentition|url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1752928X16301111|journal=Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine|volume=44|pages=54–57|doi=10.1016/j.jflm.2016.08.017}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kondo|first=Shintaro|last2=Townsend|first2=Grant C.|last3=Yamada|first3=Hiroyuki|date=December 2005|title=Sexual dimorphism of cusp dimensions in human maxillary molars|url=http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ajpa.20084|journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology|volume=128|issue=4|pages=870–877|doi=10.1002/ajpa.20084|issn=0002-9483}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Stroud|first=J L|last2=Buschang|first2=P H|last3=Goaz|first3=P W|date=August 1994|title=Sexual dimorphism in mesiodistal dentin and enamel thickness.|url=http://www.birpublications.org/doi/10.1259/dmfr.23.3.7835519|journal=Dentomaxillofacial Radiology|volume=23|issue=3|pages=169–171|doi=10.1259/dmfr.23.3.7835519|issn=0250-832X}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Garn|first=Stanley M.|last2=Lewis|first2=Arthur B.|last3=Swindler|first3=Daris R.|last4=Kerewsky|first4=Rose S.|date=September 1967|title=Genetic Control of Sexual Dimorphism in Tooth Size|url=http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00220345670460055801|journal=Journal of Dental Research|volume=46|issue=5|pages=963–972|doi=10.1177/00220345670460055801|issn=0022-0345}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal|last=García‐Campos|first=Cecilia|last2=Martinón‐Torres|first2=María|last3=Martín‐Francés|first3=Laura|last4=Martínez de Pinillos|first4=Marina|last5=Modesto‐Mata|first5=Mario|last6=Perea‐Pérez|first6=Bernardo|last7=Zanolli|first7=Clément|last8=Labajo González|first8=Elena|last9=Sánchez Sánchez|first9=José Antonio|date=June 2018|title=Contribution of dental tissues to sex determination in modern human populations|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ajpa.23447|journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology|volume=166|issue=2|pages=459–472|doi=10.1002/ajpa.23447|issn=0002-9483}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite journal|last=Sorenti|first=Mark|last2=Martinón-Torres|first2=María|last3=Martín-Francés|first3=Laura|last4=Perea-Pérez|first4=Bernardo|date=2019-03-13|title=Sexual dimorphism of dental tissues in modern human mandibular molars|url=http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ajpa.23822|journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology|doi=10.1002/ajpa.23822}}</ref> |

||

=== 身長の決定 === |

=== 身長の決定 === |

||

| 61行目: | 61行目: | ||

=== フォレンジック・アーキオロジー(仮訳:法考古学) === |

=== フォレンジック・アーキオロジー(仮訳:法考古学) === |

||

法考古学者(フォレンジック・アーキオロジスト)は、発掘技術に関する専門知識を活用し、遺骨が法的に許容される方法で確実に回収されるよう支援を行う<ref name="Chicora"><cite class="citation web">[http://www.chicora.org/forensic-archaeology.html "Forensic Archaeology"]. ''Chicora Foundation''<span class="reference-accessdate">. Retrieved <span class="nowrap">August 21,</span> 2015</span>.</cite><templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles></ref>。遺骨が埋葬されている場合は、適切な発掘により、どんな証拠も無傷のまま収容されることになる。法考古学者と法人類学者の違いは、法人類学者が特に人骨学と遺体の回収について訓練され、法考古学者はより広範に検索と発見のプロセスを専門としているということである<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Schultz, Dupras|date=2008|title=The Contribution of Forensic Archaeology to Homicide Investigations|url=|journal=Homicide Studies|volume=12|issue=4|pages=399–413| |

法考古学者(フォレンジック・アーキオロジスト)は、発掘技術に関する専門知識を活用し、遺骨が法的に許容される方法で確実に回収されるよう支援を行う<ref name="Chicora"><cite class="citation web">[http://www.chicora.org/forensic-archaeology.html "Forensic Archaeology"]. ''Chicora Foundation''<span class="reference-accessdate">. Retrieved <span class="nowrap">August 21,</span> 2015</span>.</cite><templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles></ref>。遺骨が埋葬されている場合は、適切な発掘により、どんな証拠も無傷のまま収容されることになる。法考古学者と法人類学者の違いは、法人類学者が特に人骨学と遺体の回収について訓練され、法考古学者はより広範に検索と発見のプロセスを専門としているということである<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Schultz, Dupras|date=2008|title=The Contribution of Forensic Archaeology to Homicide Investigations|url=|journal=Homicide Studies|volume=12|issue=4|pages=399–413|doi=10.1177/1088767908324430|pmid=}}</ref>。加えて、考古学者は発掘区域およびその周辺にある遺物の調査発見の訓練も受けている。これらの遺物は、例えば結婚指輪やたばこの吸い殻、靴の跡など、潜在的に見込みのある証拠まであらゆるものが含まれる<ref name="Nawrocki arch"><cite class="citation web">Nawrocki, Stephen P. (June 27, 2006). [https://web.archive.org/web/20151129102446/http://archlab.uindy.edu/documents/ForensicArcheo.pdf "An Outline Of Forensic Archeology"] <span class="cs1-format">(PDF)</span>. Archived from [http://archlab.uindy.edu/documents/ForensicArcheo.pdf the original] <span class="cs1-format">(PDF)</span> on 2015-11-29<span class="reference-accessdate">. Retrieved <span class="nowrap">August 21,</span> 2015</span>.</cite><templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles></ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Sigler-Eisenberg|date=1985|title=Forensic Research: Expanding the Concept of Applied Archaeology|url=|journal=American Antiquity|doi=|pmid=}}</ref>。 |

||

法考古学者(仮)は、現場の調査、捜査、骨格の回収を支援するといった3つの主要分野に関与するが、あくまで1つの側面に過ぎない。 |

法考古学者(仮)は、現場の調査、捜査、骨格の回収を支援するといった3つの主要分野に関与するが、あくまで1つの側面に過ぎない。 |

||

大量殺人またはテロ(殺人、集団殺害、戦争犯罪、その他の人権侵害)の現場を処理することも、法考古学者が関わる仕事の一つである<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Schultz, Dupras|date=2008|title=The Contribution of Forensic Archaeology to Homicide Investigations|url=|journal=Homicide Studies|volume=12|issue=4|pages=399–413| |

大量殺人またはテロ(殺人、集団殺害、戦争犯罪、その他の人権侵害)の現場を処理することも、法考古学者が関わる仕事の一つである<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Schultz, Dupras|date=2008|title=The Contribution of Forensic Archaeology to Homicide Investigations|url=|journal=Homicide Studies|volume=12|issue=4|pages=399–413|doi=10.1177/1088767908324430|pmid=}}</ref>。 |

||

法考古学者は、潜在的に[[墓穴|重要な場所]]を発見する訓練を受けている。遺体が埋葬されている場所では地中で少量の土が形成される。緩い土と分解している体からの栄養素は、周辺地域とは異なる種類の植物の成長を促進するため、法考古学者はこれらの土壌の違いなどから、有望そうな場所を特定することができる。典型的なケースでは、通常、墓地はその周辺より緩く、より有機的な土壌を持っている<ref name="sfu arch"><cite class="citation web">[http://www.sfu.museum/forensics/eng/pg_media-media_pg/archaeologie-archaeology/ "Forensic Archaeology"]. Simon Fraser University<span class="reference-accessdate">. Retrieved <span class="nowrap">August 21,</span> 2015</span>.</cite><templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles></ref>。 |

法考古学者は、潜在的に[[墓穴|重要な場所]]を発見する訓練を受けている。遺体が埋葬されている場所では地中で少量の土が形成される。緩い土と分解している体からの栄養素は、周辺地域とは異なる種類の植物の成長を促進するため、法考古学者はこれらの土壌の違いなどから、有望そうな場所を特定することができる。典型的なケースでは、通常、墓地はその周辺より緩く、より有機的な土壌を持っている<ref name="sfu arch"><cite class="citation web">[http://www.sfu.museum/forensics/eng/pg_media-media_pg/archaeologie-archaeology/ "Forensic Archaeology"]. Simon Fraser University<span class="reference-accessdate">. Retrieved <span class="nowrap">August 21,</span> 2015</span>.</cite><templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles></ref>。 |

||

2020年1月25日 (土) 18:18時点における版

法人類学(ほうじんるいがく、英: Forensic anthropology、フォレンジック・アンスロポロジー)とは、司法の文脈における、解剖学的な応用人類学。考古学や化石学といった分野からの応用も含む[1] 。

概要

法人類学者は、腐乱、焼失、切断、その他認識が難しい状態の遺体から身元を特定するための調査を支援し、法医病理学者、法歯学医、そして犯罪捜査の刑事たちと同様に、専門家証人(日本でいう鑑定証人)として法廷に立ち、証言を行うものである。

遺体からの身元特定は、骨格に存在する物理的なマーカーを使用して、被害者の年齢、性別、身長、人種的祖先の決定を行う。またその際、個人の外見的特徴だけでなく、その死因や、骨折などの過去の外傷・医療処置の有無、骨癌などの疾患なども明らかになる場合がある。

現代における、骨から個人の身元を特定するという手法は、過去の人類学者たちによる様々な貢献と研究の歴史のたまものである。収集された何千もの骨格標本を研究し、特定の母集団内での差異を分析することにより、法人類学者は身体的特徴に基づく推定を行うことができるようになった。これらをふまえて、法人類学は、この20世紀、専門訓練を受けた多くの人類学者や、多数の研究機関も生まれ、1つの法科学的専門分野として完全に認められるまでに発展した。

現代の用途

法人類学は、法科学の中でよく確立された分野である。遺体が長期間発見されず、人を識別する身体的特徴が失われている場合などにおいて、法人類学者が必要とされことになる。

また、法人類学者は、身元不明の遺体から身体的特徴を再構築し、そのデータをNational Crime Information Center(米国)[2]や、国際的なインターポールのデータベースなど、行方不明人のデータベースに登録することによって、身元の特定に役立てている[3]。

法人類学者は、戦争犯罪や大規模事件の捜査の支援も行っている。911テロ[4]、アロー航空1285便墜落事故[5]、USエアー427便墜落事故といった、通常の身元確認は不可能に近い、非常に悲惨な事故などの犠牲者について、その身元特定に関わる役割を任されてきた[6]。人類学者はまた、実際の事件から年月が経過した大量虐殺の犠牲者たちの身元を特定する手助けもしてきた。ルワンダ虐殺[7]やスレブレニツァの虐殺などの調査も、法人類学者が実施してきたものである[8]。

現在、欧州法人類学協会、英国法人類学協会、および米国法人類学者協会といった組織は、法人類学の発展および基準の策定に関するガイドラインの提供をしている。

歴史

初期の歴史

遺体の法科学的調査における人類学の活用は、人類学の科学分野としての地位と形質人類学の発展によるものである。人類学の分野はアメリカで始まり、20世紀初頭には正当な科学と認められつつあった[9]。アーネスト・フートンは、形質人類学の分野を開拓し、米国でにおいてフルタイムの教職を歴任した最初の形質人類学者となった[10]。彼は、アメリカ物理人類学者協会の創設者(AlešHrdlička)と共に組織委員会のメンバーでもある。フートンの弟子たちは、その後20世紀初頭、最初の形質人類学博士号プログラム創立することになる[11][12]。

トーマス・ウィンゲート・トッドは、初期の人類学者としてこの分野の確立に貢献した事で、特に著名である。彼は人間の骨格の大規模なコレクションを作成し、合計で3,300体の人骨、600のサルの骨格、および3,000の哺乳類の骨格を収集している[13]。このデータは現代でも様々な研究に用いられており、現代人類学への大きな貢献となっている。

彼はまた、恥骨接合の特性に基づき、年齢推定値を算出する方法も生み出した。この基準は現在更新されてはいるもものの、白骨化した遺骨の年齢範囲を絞り込むために、現代でも法人類学者によって使用されている[14]。

これらの初期の人類学における先駆者は、人類学を確立したものの、法人類学としての認識を得ることになるのは、トッドの教え子でもあった、ウィルトン. M. クロッグマンが登場してからである。

法人類学の発展

ウィルトン・クロッグマンは、1940年代、法科学における人類学者の潜在的な価値を積極的に啓蒙する最初の人類学者であった。この時期になって、人類学者はアメリカのFBIなどの連邦政府機関で公式に協力するようになった。1950年代には、アメリカ陸軍は朝鮮戦争中の戦争の犠牲者の身元特定に法人類学者を採用している[12]。法人類学の正式な起源はこの時である。1940年代に開発され、戦争によって改良された方式は、現代の法人類学者が利用する手法の元となっている。

アメリカでは、1950年代から1960年代にかけて、法人類学の専門化が始まった。これは、ちょうど検死官(Coroner)が行っていた事を監察医(Medical Examiner)が行うようになった時期と重なっている[12]。法人類学がアメリカ法科学アカデミーの一分野として認知されるようになったのもこの頃である[15]。

現代では、法人類学者が、知名度の高い事件に取り組むようになるにつれて、法人類学に対する世間の関心や注目も集まり始めた。有名な事件としては、エド・ゲインによって殺害された犠牲者の身元特定を行ったのは人類学者チャールズ・メルブスである[16]。

手法

調査の過程では、法人類学者はしばしば、遺体の性別、身長、年齢、人種的先祖といった事を推定するよう求められる。方法としては、1つに骨学に関する知識と骨格内で発生する様々な特徴を見るという手法がとられる。

性別の決定

性別は、骨の性別的な固有の違いを探すことによって決定される。中でも骨盤は、性別の決定に極めて有用であり、もし入手可能であれば、非常に高いレベルの精度で決定することができる[17]。

しかしながら、骨盤は常に存在するわけではないので、法人類学者は、性別間で明確な特徴を有する頭蓋骨といった、他の骨格上の違いも知っておく必要がある[18] [19]。

[20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27]

身長の決定

身長の推定は、過去長い間の研究における積み重ねのデータから導きだされた一連の式に基づいてなされる。一般的には足の大腿骨 、脛骨、および腓骨[28]、さらに腕の上腕骨、尺骨、橈骨も測定のために使用される場合がある[29] [30] [31]。身長を決定する際には、個人のおおよその年齢を確認することも重要である。人は年をとるにつれて骨格の収縮を起こし、30歳を過ぎると、人は10年ごとに身長の約1センチメートルを失うからである[28]。

年齢の決定

年齢の決定方法は、対象が成人か子供かによって異なる。21歳未満の子供の年齢は、通常は歯を調べることによって決定される[32]。歯が利用できない時は、成長板に基づいて判定するる[33]。完全な骨格が利用可能な場合は、骨の数を数え、大人の骨数(206本)と比較する(子供の骨はまだ融合していないため、数がずっと多い)。

成人の骨は、成人期に達してもほとんど変化しないため、子供よりも難しい[34]。可能な方法としては、顕微鏡で調べることである。骨の成長が止まっても、新しい骨は骨髄によって常に形成されている[33]。もう一つは、骨の上の関節炎の指標を探すことである[35]。これらの指標を組み合わせ、法人類学者は個人の推定年齢の範囲を絞り込む。

祖先の決定

人種的祖先の決定は、通常、3つの歴史的グループ、つまり、コーカソイド、モンゴロイド、およびネグロイドに分類される。しかし、これらの分類は、国際結婚の割合が高まり、困難なものになっている[36]。通常、上顎はそれぞれに属する基本的な形状をもつため、頬骨弓と鼻孔などと共に、その人種的祖先を決定するために用いられる[37] [38]。

これら形状を測定し、その計測値を元に、複雑な数式を用いて計算するFORDISCと呼ばれるプログラムも作成されている[39]。このプログラムは既存の多くの測定値のデータを保持しており、推定される人種的祖先を導き出すものである。これは物議を醸す場合もあるが、対象者を絞り込むために警察の調査でしばしば必要とされる。

小分野

フォレンジック・アーキオロジー(仮訳:法考古学)

法考古学者(フォレンジック・アーキオロジスト)は、発掘技術に関する専門知識を活用し、遺骨が法的に許容される方法で確実に回収されるよう支援を行う[40]。遺骨が埋葬されている場合は、適切な発掘により、どんな証拠も無傷のまま収容されることになる。法考古学者と法人類学者の違いは、法人類学者が特に人骨学と遺体の回収について訓練され、法考古学者はより広範に検索と発見のプロセスを専門としているということである[41]。加えて、考古学者は発掘区域およびその周辺にある遺物の調査発見の訓練も受けている。これらの遺物は、例えば結婚指輪やたばこの吸い殻、靴の跡など、潜在的に見込みのある証拠まであらゆるものが含まれる[42][43]。

法考古学者(仮)は、現場の調査、捜査、骨格の回収を支援するといった3つの主要分野に関与するが、あくまで1つの側面に過ぎない。

大量殺人またはテロ(殺人、集団殺害、戦争犯罪、その他の人権侵害)の現場を処理することも、法考古学者が関わる仕事の一つである[41]。

法考古学者は、潜在的に重要な場所を発見する訓練を受けている。遺体が埋葬されている場所では地中で少量の土が形成される。緩い土と分解している体からの栄養素は、周辺地域とは異なる種類の植物の成長を促進するため、法考古学者はこれらの土壌の違いなどから、有望そうな場所を特定することができる。典型的なケースでは、通常、墓地はその周辺より緩く、より有機的な土壌を持っている[44]。

フォレンジック・タフォノミー (仮訳:法化石学)

埋葬されていた骨格の調査は、しばしば肉体の分解に影響する環境要因を考慮に入れる必要がある。タフォノミーとは、土壌、水、および植物や昆虫、その他の動物との作用によって引き起こされる、人間の遺体の死後変化についての研究である[45]。これらの影響を研究するために、特別な研究施設(“Body farm”)が複数の大学で設置されており、学生と教員は、寄贈された死体の分解過程における環境影響を研究している[46]。

フォレンジック・タフォノミーでは、生物タフォノミーと地理タフォノミーの2つの異なるセクションに分けられている。生物分類学は、環境が身体の分解にどのように影響するかの研究で、具体的には、どのようにして分解が起こったのかを確認するための生物学的痕跡調査である[47] [48]。

地理タフォノミーは、体の分解がどのように環境に影響を与えるかの調査である。検査には、土壌がどのように乱されたか、周辺地域のpH変化、周囲の植物成長の速度変化などが含まれる[47]。これらの特性を調べることによって、死亡時の状況とその後の出来事のタイムラインを知ることができる[48]。

教育

一般的に、法人類学者の多くは、人類学の学士号を取得している。大学での学習は身体学と骨学に焦点を合わせ、生物学、化学、解剖学、遺伝学などの幅広いコースを受講することが推奨されている[49]。

その後、大学院に進み、形質人類学で博士号を取得し、骨学、法医学、および考古学の課程を修了する場合が多い。法人類学での専門職を希望する場合は解剖学クラスだけでなく、調査機関や実践人類学者とのインターンシップを通して解剖の経験を積むことも推奨されている[1]。教育要件が満たされると、その地域の法人類学協会による認定を受けることができる。ヨーロッパでは、法人類学協会[50]でのIALM試験、アメリカの法人類学委員会による認定試験をクリアするという事を意味している [51]

通常、ほとんどの法人類学者は大学または研究施設のどちらかで雇用されており、パートタイムで法科学的な仕事を行うケースが多い。ただ、一部は、政府、また国際機関においてフルタイムで働いている人も存在する[52]。

倫理

他の分野と同様に、法人類学者は司法制度における仕事として高レベルの倫理基準に拘束される。故意または誤って何らかの証拠を提出した場合、違反の重大度に応じて当局によって制裁、罰金、または投獄される可能性がある。また、利益相反の立場を明らかにしなかったり、発見事項の隠蔽などを行った個人は、懲戒処分に直面する可能性もある[53]。法人類学者は、調査の過程で公平であり続けることが重要で、もし偏見が認められた場合、犯人を裁判にかけるための法廷において、証拠自体に疑念を持たれる可能性があるからである[54]。

著名な法人類学者

アメリカにおいては100人前後の学会で認められた法人類学者がいると言う[55]。

- キャシー・ライクス [56]- ノースウェスタン大学にて自然人類学の理学博士号(Ph.D)を取得、ノースカロライナ大学の人類学准教授。BONES (テレビドラマ)の元ネタとなった本をはじめ数々の書籍も出しており、ニューヨーク・タイムズのベストセラー作家。ルワンダ国際戦犯法廷他、多数の裁判でも専門の法人類学者として証人台に立つ。

関連項目

出典

- ^ a b Nawrocki, Stephen P. (June 27, 2006). "An Outline Of Forensic Anthropology" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-15. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "National Crime Information Center: NCIC Files". FBI. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ "Notices". INTERPOL. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ McShane, Larry (July 19, 2014). "Forensic pathologist details grim work helping identify bodies after 9/11 in new book". Daily News. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ Hinkes, MJ (July 1989). "The role of forensic anthropology in mass disaster resolution". Aviat Space Environ Med. 60 (7 Pt 2): A60–3. PMID 2775124.

- ^ "College Professor Gets the Call to Examine Plane Crashes and Crime Scenes". PoliceOne. July 28, 2002. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ Nuwer, Rachel (November 18, 2013). "Reading Bones to Identify Genocide Victims". The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ Elson, Rachel (May 9, 2004). "Piecing together the victims of genocide / Forensic anthropologist identifies remains, but questions about their deaths remain". SFGate. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ Stewart, T. D. (1979). "In the Uses of Anthropology". Forensic Anthropology. Special Publication (11): 169–183.

- ^ Shapiro, H. L. (1954). "Earnest Albert Hooton 1887-1954". American Anthropologist. 56 (6): 1081–1084. doi:10.1525/aa.1954.56.6.02a00090.

- ^ Spencer, Frank (1981). "The Rise of Academic Physical Anthropology in the United States (1880-1980)". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 56 (4): 353–364. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330560407.

- ^ a b c Snow, Clyde Collins (1982). "Forensic Anthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 11: 97–131. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.11.100182.000525.

- ^ Cobb, W. Montague (1959). "Thomas Wingate Todd, M.B., Ch.B., F.R.C.S. (Eng.), 1885-1938". Journal of the National Medical Association. 51 (3): 233–246. PMC 2641291. PMID 13655086.

- ^ Buikstra, Jane E.; Ubelaker, Douglas H. (1991). "Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains". Arkansas Archaeology Survey Research Series. 44.

- ^ Buikstra, Jane E.; King, Jason L.; Nystrom, Kenneth (2003). "Forensic Anthropology and Bioarchaeology in the American Anthropologist: Rare but Exquisite Gems". American Anthropologist. 105 (1): 38–52. doi:10.1525/aa.2003.105.1.38.

- ^ Golda, Stephanie (2010). "A Look at the History of Forensic Anthropology: Tracing My Academic Genealogy". Journal of Contemporary Anthropology. 1 (1).

- ^ "Identification Of Skeletal Remains" (PDF). forensicjournals.com. November 5, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "Differences Between Male Skull and Female Skull". juniordentist.com. September 24, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "Male or Female". Smithsonian National Museum of National History. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ Cardoso, Hugo F.V. (January 2008). “Sample-specific (universal) metric approaches for determining the sex of immature human skeletal remains using permanent tooth dimensions”. Journal of Archaeological Science 35 (1): 158–168. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.02.013.

- ^ Harris, Edward F.; Lease, Loren R. (November 2005). “Mesiodistal tooth crown dimensions of the primary dentition: A worldwide survey”. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 128 (3): 593–607. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20162. ISSN 0002-9483.

- ^ Paknahad, Maryam; Vossoughi, Mehrdad; Ahmadi Zeydabadi, Fatemeh (November 2016). “A radio-odontometric analysis of sexual dimorphism in deciduous dentition”. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 44: 54–57. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2016.08.017.

- ^ Kondo, Shintaro; Townsend, Grant C.; Yamada, Hiroyuki (December 2005). “Sexual dimorphism of cusp dimensions in human maxillary molars”. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 128 (4): 870–877. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20084. ISSN 0002-9483.

- ^ Stroud, J L; Buschang, P H; Goaz, P W (August 1994). “Sexual dimorphism in mesiodistal dentin and enamel thickness.”. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology 23 (3): 169–171. doi:10.1259/dmfr.23.3.7835519. ISSN 0250-832X.

- ^ Garn, Stanley M.; Lewis, Arthur B.; Swindler, Daris R.; Kerewsky, Rose S. (September 1967). “Genetic Control of Sexual Dimorphism in Tooth Size”. Journal of Dental Research 46 (5): 963–972. doi:10.1177/00220345670460055801. ISSN 0022-0345.

- ^ García‐Campos, Cecilia; Martinón‐Torres, María; Martín‐Francés, Laura; Martínez de Pinillos, Marina; Modesto‐Mata, Mario; Perea‐Pérez, Bernardo; Zanolli, Clément; Labajo González, Elena et al. (June 2018). “Contribution of dental tissues to sex determination in modern human populations”. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 166 (2): 459–472. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23447. ISSN 0002-9483.

- ^ Sorenti, Mark; Martinón-Torres, María; Martín-Francés, Laura; Perea-Pérez, Bernardo (2019-03-13). “Sexual dimorphism of dental tissues in modern human mandibular molars”. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23822.

- ^ a b "Biological Profile / Stature" (PDF). Simon Fraser University. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ Mall, G. (March 1, 2001). "Sex determination and estimation of stature from the long bones of the arm". Forensic Sci Int. 117 (1–2): 23–30. doi:10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00445-x. PMID 11230943.

- ^ Hawks, John (September 6, 2011). "Predicting stature from bone measurements". Archived from the original on 2015-09-15. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ Garwin, April (2006). "Stature". redwoods.edu. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "Skeletons are good age markers because teeth and bones mature at fairly predictable rates" (PDF). Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "Young or Old?". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Quick Tips: How To Estimate The Chronological Age Of A Human Skeleton — The Basics". All Things AAFS!. August 20, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Skeletons as Forensic Evidence". Archived from the original on August 28, 2015. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Anthropological Views". National Institute of Health. June 5, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Analysis of Skeletal Remains". Westport Public Schools. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Activity: Can You Identify Ancestry?" (PDF). Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Ancestry, Race, and Forensic Anthropology". Observation Deck. March 31, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Forensic Archaeology". Chicora Foundation. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ a b Schultz, Dupras (2008). “The Contribution of Forensic Archaeology to Homicide Investigations”. Homicide Studies 12 (4): 399–413. doi:10.1177/1088767908324430.

- ^ Nawrocki, Stephen P. (June 27, 2006). "An Outline Of Forensic Archeology" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-29. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ Sigler-Eisenberg (1985). “Forensic Research: Expanding the Concept of Applied Archaeology”. American Antiquity.

- ^ "Forensic Archaeology". Simon Fraser University. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ Pokines, James; Symes, Steven A. (2013-10-08). Manual of Forensic Taphonomy. CRC Press. ISBN 9781439878415.

- ^ Killgrove, Kristina (June 10, 2015). "These 6 'Body Farms' Help Forensic Anthropologists Learn To Solve Crimes". forbes.com. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "Forensic taphonomy". itsgov.com. December 8, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Nawrocki, Stephen P. (June 27, 2006). "An Outline Of Forensic Taphonomy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ Hall, Shane. "Education Required for Forensic Anthropology". Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "FASE/IALM Certification". Forensic Anthropology Society of Europe. Archived from the original on 2015-02-25. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "Certification Examination General Guidelines" (PDF). American Board of Forensic Anthropology. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "ABFA - American Board of Forensic Anthropology". Archived from the original on August 29, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "Code of Ethics and Conduct" (PDF). Scientific Working Group for Forensic Anthropology. June 1, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ "Code of Ethics and Conduct" (PDF). American Board of Forensic Anthropology. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ “Kathy Reichs Digging up ‘Bones’”. kathyreichs.com. 2019年5月13日閲覧。

- ^ 現代外国人名録2016. “キャシー ライクスとは”. コトバンク. 2019年6月5日閲覧。