ARNTL

アリル炭化水素受容体核移行因子様タンパク質1(Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator like 1)はヒトのARNTL遺伝子にコードされたタンパク質である。ARNTLはBMAL1、MOP3とも呼ばれる。(あまり一般的ではないが、BHLHE5, BMAL, BMAL1C, JAP3, PASD3, TICという呼び名も用いられる)

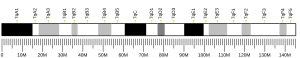

ARNTL遺伝子にはベーシック-ヘリックス-ループ-ヘリックス(bHLH)と二つのPASドメインが含まれる。ヒトのARNTL遺伝子は24個のエクソンを持つと考えられており、第11染色体のp15バンドに位置する[4]。BMAL1 タンパク質は626個のアミノ酸からなり、哺乳類における自家転写翻訳ネガティブフィードバックループ(TTFL)における正の因子の一つとして重要な役割を持ち、遺伝分子的な概日リズムにも関わる。また、BMAL1は高血圧症、 糖尿病、 肥満の関与遺伝子であることが予測されており[5][6]、BMAL1変異は不妊や糖新生・脂質新生異常を引き起こし、睡眠パターンを変化させる[7]。全ゲノム分析によって、BMAL1はヒトゲノムにおいて推定150以上領域を標的としており、全ての時計遺伝子や代謝制御タンパクをコードする遺伝子も含まれる[8]。

歴史

[編集]ARNTL遺伝子は1997年、John B.Hogeneschのグループによって3月に[9] 、池田・野村のグループによって4月に [10] 、PASドメイン転写因子のスーパーファミリーの遺伝子として発見された。 ARNTLタンパク質はMOP3としても知られ、MOP4やクロック、低酸素誘導因子と二量体を形成することが分かっている。 BMAL1、ARNTLという名前は、近年の論文で採用されている。ARNTLタンパク質で最も初めに発見された概日制御における機能は、CLOCK-BMAL1(CLOCK-ARNTL)のヘテロ二量体に関係するもので、CLOCK-BMAL1はE-boxと結合しバソプレシン遺伝子の転写活性を亢進する。[11] しかし、概日リズムにおけるBMAL1遺伝子の重要性は、ノックアウトマウスが運動や他の行動において概日リズムを完全に喪失することが発見されるまで、完全には理解されていなかった。[12]

構造

[編集]結晶構造から、BMAL1タンパク質は4つのドメイン含むことが分かっている: bHLHドメイン、PAS-!, PAS-Bと呼ばれる、2つのPASドメイン、トランス活性化ドメインである。CLOCK-BMAL1の二量体化にはCLOCKとBMAL1両者のbHLH, PAS A, PAS Bドメイン、それぞれの間での強い相互作用がかかわっており、3つの異なるタンパク質界面によって左右非対称のヘテロ二量体を形成する。CLOCK-BMAL1間でのPAS-Aの相互作用は、 CLOCK PAS-Aのα-ヘリックスおよびBMAL1 PAS-Aのβ-シート間での相互作用、BMAL1 PAS-Aのα-ヘリックスとCLOCK PAS-Aのβ-シート間での相互作用からなる。[13] CLOCKとBMAL1におけるPAS-Bドメインは並列して積み重なり、これによってBMAL1 PAS-Bのβ-シートやCLOCK PAS-Bのらせん状表面におけるTry 310やPhe 423などの疎水性残基をしまい込んでいる。 特異的なアミノ酸残基との重要な相互作用は、特にCLOCKのHis 84とBMAL1 Leu 125で起こり、CLOCK-BMAL1の二量体化に重要である。[14]

機能

[編集]概日

[編集]哺乳類において、Bmal1遺伝子によってコードされるタンパク質は、PASドメインを介してカンドbHLH-PASタンパク質であるCLOCK(もしくはパラログのNPAS2)と結合し、核内でヘテロ二量体を形成する。[15] BHLHドメインを介して、このヘテロ二量体はPer(Per1, Per2)やCry(Cry1, Cry2)のプロモータ領域に位置するE-box応答領域と結合する。この結合はPER1, PER2, CRY1, CRY2タンパク質の転写翻訳を促進する。

PERとCRYタンパク質が十分量まで蓄積すると、PASモチーフを介して相互作用し、核内に移行してCLOCK-BMAL1ヘテロ二量体の転写活性を阻害する抑制複合体を形成する。 [16] この二量体はPerとCry遺伝子の転写を抑制し、PERとCRYのタンパク質レベルを減少させる。 この転写翻訳ネガティブフィードバックループ(TTFL)は、細胞質内でカゼインキナーゼ1εやδ(CK1εやCK1δ)によるPERタンパク質のリン酸化によって修飾され、これらのタンパク質の26Sプロテオソームによる分解を仲介する。[17] SIRT1もBMAL1-CLOCKのヘテロ二量体を脱アセチル化させ、概日的なPERタンパク質の分解を制御している。[18] PERタンパク質の分解は大型のタンパク質複合体の形成を阻害し、これによってBMAL1-CLOCKヘテロ二量体による転写活性阻害作用を妨害する。CRYタンパク質もFBXL3タンパク質によってポリユビキチン化による分解を引き起こされ、同じくBMAL1-CLOCKヘテロ二量体の阻害作用が妨害される。これによってPerとCry遺伝子の転写が再開される。夜行性マウスのTTFLループにおいて、Bmal1遺伝子の転写レベルのピークはCT18にみられ、これは主観真夜中で、Per,Cryなどの主観真昼のCT6にピークを持つ時計遺伝子とは逆位相をとる。このプロセスは約24時間の長さを持ち、これは分子メカニズムがリズム性であるという考えを支持する。[19]

Bmal1活性の制御

[編集]上述したTTFLループの概日制御に加えて、Bmal1転写はBmal1のプロモータに含まれる、レチノイン酸関連オーファン受容体応答領域結合サイト(RORE)によっても制御される。CLOCK-BMAL1ヘテロ二量体は、Rev-ErbやROR遺伝子のプロモータ領域に存在するE-boxにも結合し、REV-ERBやRORタンパク質の転写翻訳を促進する。REV-ERBαやRORタンパク質は、セカンダリーフィードバックループを介し、競合してBmal1プロモータ内のREV-ERB/ROR応答領域に結合し、BMAL1発現を制御する。同じファミリー内の他の核受容体(NR1D2(Rev-erbβ);NR1F2(ROR-β);NR1F3(ROR-γ))も、Bmal1転写活性に同じように作用する。[20][21][22][23]

複数のBMAL1の翻訳後修飾はCLOCK/BMAL1のフィードバックループを指示する。BMAL1はリン酸化によってユビキチン化、分解の標的となる。BMAL1のアセチル化はCRY1をリクルートし、CLOCK/BMAL1のトランス活性化を抑制する。[24] 小型のSUMO3によるBMAL1のSUMO化は、核でのBMAL1のユビキチン化の合図となる。これによって、CLOCK/BMAL1ヘテロ二量体のトランス活性化が誘発される。[25] CLOCK/BMAL1のトランス活性[26] は、カゼインキナーゼ1εによるリン酸化によって亢進され、MAPKによるリン酸化によって抑制される。[27] CK2αによるリン酸化はBMAL1の細胞内局在を制御し、 [28] GSK3Bによるリン酸化はBMAL1の安定性をコントロールし、リン酸化を誘発する。[29]

その他の機能

[編集]Arntl遺伝子はラットにおいて、第1染色体の高血圧推定遺伝子座に存在する。 この座位の一塩基多型 (SNPs)研究によって、Arntlをコードする配列において2つの多型が発見された。この部分はII型糖尿病と高血圧に関連している。 ラットモデルをヒトモデルに適用した時、この研究からArntl遺伝子多型のII型糖尿病病理の原因に関わる働きが示唆された。[30] 最近の表現型データから、[31] ArntlやパートナーのClockは[32] 、グルコース恒常性や代謝に関わっていると示唆されており、これら遺伝子の破壊によって高インスリン症や糖尿病が引き起こされる。[33] 他の機能に関して、ある研究ではCLOCK/BMAL1複合体がヒトのLDLRプロモータの活性を亢進することが示されており、このことからArntl遺伝子はコレステロール恒常性にも関わると示唆されている。[34] 加えて、Arntl遺伝子は他の時計遺伝子の発現と連動しながら発現するが、双極性障害では低下することが分かっている。[35] Arntl、Npas2、Per2もまた、ヒトの季節性情動障害に関わっている。[36] 最後に、Arntlは機能性遺伝子診断によって、P53遺伝子経路の有力な制御子であることが同定された。これはがん細胞での概日リズムにArntlが関わっていることを示唆する。[37]

ノックアウト研究

[編集]Arntl遺伝子は哺乳類時計遺伝子制御ネットワークの重要な構成要素である。 ネットワーク感受性における重要な点は、モデルマウスで一つの遺伝子をノックアウトさせただけで分子および行動のリズム性が失われるということである。 時計への異常に加えて、Arntl nullのマウスは生殖異常[38]のほかに、低身長、早老[39] 、進行性関節症[40] を示し、その結果、野生型よりも運動量が低下する。 しかし、最近の研究から、ArntlとパラログのBmal2のあいだで、概日機能における機能重複が存在するということが示唆されている。[41]

相互作用

[編集]Arntlは以下の遺伝子と相互作用する :

参照

[編集]- Arntl2 - Arntl(Bmal1)パラログ。helix-loop-helix PASドメイン転写因子をコード。 BMAL2タンパク質はCLOCKタンパク質とヘテロ二量体を形成。低酸素症にも関わる。[47]

- Cycle - ショウジョウバエにおけるオルソログ。

- アリル炭化水素受容体核内移行因子(Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator: ARNT) - ARNTLの名の元になっている。

- アリル炭化水素受容体(Aryl hydrocarbon receptor: AhR) - 上記の名の元。

参考文献

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000055116 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “ARNTL aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like [ Homo sapiens (human) ]”. National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2018年1月31日閲覧。

- ^ “The major circadian pacemaker ARNT-like protein-1 (BMAL1) is associated with susceptibility to gestational diabetes mellitus”. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 99 (2): 151–7. (February 2013). doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2012.10.015. PMID 23206673.

- ^ “Clock genes in hypertension: novel insights from rodent models”. Blood Pressure Monitoring 19 (5): 249–54. (October 2014). doi:10.1097/MBP.0000000000000060. PMC 4159427. PMID 25025868.

- ^ “ARNTL Gene”. Gene Cards: The Human Genome Compendium. Lifemap Sciences, Inc.. 2018年1月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Genome-wide profiling of the core clock protein BMAL1 targets reveals a strict relationship with metabolism”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 30 (24): 5636–48. (December 2010). doi:10.1128/MCB.00781-10. PMC 3004277. PMID 20937769.

- ^ “Characterization of a subset of the basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS superfamily that interacts with components of the dioxin signaling pathway”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 272 (13): 8581–93. (March 1997). doi:10.1074/jbc.272.13.8581. PMID 9079689.

- ^ “cDNA cloning and tissue-specific expression of a novel basic helix-loop-helix/PAS protein (BMAL1) and identification of alternatively spliced variants with alternative translation initiation site usage”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 233 (1): 258–64. (April 1997). doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.6371. PMID 9144434.

- ^ “A molecular mechanism regulating rhythmic output from the suprachiasmatic circadian clock”. Cell 96 (1): 57–68. (January 1999). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80959-9. PMID 9989497.

- ^ “Mop3 is an essential component of the master circadian pacemaker in mammals”. Cell 103 (7): 1009–17. (December 2000). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00205-1. PMC 3779439. PMID 11163178.

- ^ “Crystal structure of the heterodimeric CLOCK:BMAL1 transcriptional activator complex”. Science 337 (6091): 189–94. (July 2012). Bibcode: 2012Sci...337..189H. doi:10.1126/science.1222804. PMC 3694778. PMID 22653727.

- ^ “Intermolecular recognition revealed by the complex structure of human CLOCK-BMAL1 basic helix-loop-helix domains with E-box DNA”. Cell Research 23 (2): 213–24. (February 2013). doi:10.1038/cr.2012.170. PMC 3567813. PMID 23229515.

- ^ “Circadian rhythms, the molecular clock, and skeletal muscle”. Journal of Biological Rhythms 30 (2): 84–94. (April 2015). doi:10.1177/0748730414561638. PMC 4470613. PMID 25512305.

- ^ “Circadian rhythms - from genes to physiology and disease”. Swiss Medical Weekly 144: w13984. (2014). doi:10.4414/smw.2014.13984. PMID 25058693.

- ^ “The Tau mutation of casein kinase 1ε sets the period of the mammalian pacemaker via regulation of Period1 or Period2 clock proteins”. Journal of Biological Rhythms 29 (2): 110–8. (April 2014). doi:10.1177/0748730414520663. PMC 4131702. PMID 24682205.

- ^ “SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation”. Cell 134 (2): 317–28. (July 2008). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.050. PMID 18662546.

- ^ “A transcription factor response element for gene expression during circadian night”. Nature 418 (6897): 534–9. (August 2002). Bibcode: 2002Natur.418..534U. doi:10.1038/nature00906. PMID 12152080.

- ^ “The orphan nuclear receptor RORalpha regulates circadian transcription of the mammalian core-clock Bmal1”. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 12 (5): 441–8. (May 2005). doi:10.1038/nsmb925. PMID 15821743.

- ^ “Differential control of Bmal1 circadian transcription by REV-ERB and ROR nuclear receptors”. Journal of Biological Rhythms 20 (5): 391–403. (October 2005). doi:10.1177/0748730405277232. PMID 16267379.

- ^ “System-level identification of transcriptional circuits underlying mammalian circadian clocks”. Nature Genetics 37 (2): 187–92. (February 2005). doi:10.1038/ng1504. PMID 15665827.

- ^ Takahashi, Joseph S., ed (February 2008). “Redundant function of REV-ERBα and β and non-essential role for Bmal1 cycling in transcriptional regulation of intracellular circadian rhythms”. PLoS Genetics 4 (2): e1000023. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000023. PMC 2265523. PMID 18454201.

- ^ “CLOCK-mediated acetylation of BMAL1 controls circadian function”. Nature 450 (7172): 1086–90. (December 2007). Bibcode: 2007Natur.450.1086H. doi:10.1038/nature06394. PMID 18075593.

- ^ “Dual modification of BMAL1 by SUMO2/3 and ubiquitin promotes circadian activation of the CLOCK/BMAL1 complex”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 28 (19): 6056–65. (October 2008). doi:10.1128/MCB.00583-08. PMC 2546997. PMID 18644859.

- ^ “The circadian regulatory proteins BMAL1 and cryptochromes are substrates of casein kinase Iepsilon”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (19): 17248–54. (May 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.m111466200. PMC 1513548. PMID 11875063.

- ^ “Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylates and negatively regulates basic helix-loop-helix-PAS transcription factor BMAL1”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (1): 267–71. (January 2002). doi:10.1074/jbc.m107850200. PMID 11687575.

- ^ “CK2alpha phosphorylates BMAL1 to regulate the mammalian clock”. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 16 (4): 446–8. (April 2009). doi:10.1038/nsmb.1578. PMID 19330005.

- ^ “Regulation of BMAL1 protein stability and circadian function by GSK3beta-mediated phosphorylation”. PLoS One 5 (1): e8561. (January 2010). Bibcode: 2010PLoSO...5.8561S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008561. PMID 20049328.

- ^ “Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like (BMAL1) is associated with susceptibility to hypertension and type 2 diabetes”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (36): 14412–7. (September 2007). Bibcode: 2007PNAS..10414412W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703247104. PMC 1958818. PMID 17728404.

- ^ “BMAL1 and CLOCK, two essential components of the circadian clock, are involved in glucose homeostasis”. PLoS Biology 2 (11): e377. (November 2004). doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020377. PMC 524471. PMID 15523558.

- ^ “Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian Clock mutant mice”. Science 308 (5724): 1043–5. (May 2005). Bibcode: 2005Sci...308.1043T. doi:10.1126/science.1108750. PMC 3764501. PMID 15845877.

- ^ “Disruption of the clock components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinaemia and diabetes”. Nature 466 (7306): 627–31. (July 2010). Bibcode: 2010Natur.466..627M. doi:10.1038/nature09253. PMC 2920067. PMID 20562852.

- ^ “Circadian regulation of low density lipoprotein receptor promoter activity by CLOCK/BMAL1, Hes1 and Hes6”. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 44 (11): 642–52. (November 2012). doi:10.3858/emm.2012.44.11.073. PMC 3509181. PMID 22913986.

- ^ “Assessment of circadian function in fibroblasts of patients with bipolar disorder”. Molecular Psychiatry 14 (2): 143–55. (February 2009). doi:10.1038/mp.2008.10. PMID 18301395.

- ^ “Three circadian clock genes Per2, Arntl, and Npas2 contribute to winter depression”. Annals of Medicine 39 (3): 229–38. (2007). doi:10.1080/07853890701278795. PMID 17457720.

- ^ “A large scale shRNA barcode screen identifies the circadian clock component ARNTL as putative regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway”. PLoS One 4 (3): e4798. (2009). Bibcode: 2009PLoSO...4.4798M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004798. PMC 2653142. PMID 19277210.

- ^ “Circadian rhythms and reproduction”. Reproduction 132 (3): 379–92. (September 2006). doi:10.1530/rep.1.00614. PMID 16940279.

- ^ “A role of the circadian system and circadian proteins in aging”. Ageing Research Reviews 6 (1): 12–27. (May 2007). doi:10.1016/j.arr.2007.02.003. PMID 17369106.

- ^ “Progressive arthropathy in mice with a targeted disruption of the Mop3/Bmal-1 locus”. Genesis 41 (3): 122–32. (March 2005). doi:10.1002/gene.20102. PMID 15739187.

- ^ “Circadian clock gene Bmal1 is not essential; functional replacement with its paralog, Bmal2”. Current Biology 20 (4): 316–21. (February 2010). doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.034. PMC 2907674. PMID 20153195.

- ^ “Identification of a novel basic helix-loop-helix-PAS factor, NXF, reveals a Sim2 competitive, positive regulatory role in dendritic-cytoskeleton modulator drebrin gene expression”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 24 (2): 608–16. (January 2004). doi:10.1128/MCB.24.2.608-616.2004. PMC 343817. PMID 14701734.

- ^ “Regulation of CLOCK and MOP4 by nuclear hormone receptors in the vasculature: a humoral mechanism to reset a peripheral clock”. Cell 105 (7): 877–89. (June 2001). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00401-9. PMID 11439184.

- ^ “Transactivation mechanisms of mouse clock transcription factors, mClock and mArnt3”. Genes to Cells 5 (9): 739–47. (September 2000). doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00363.x. PMID 10971655.

- ^ “Cryptochrome 1 regulates the circadian clock through dynamic interactions with the BMAL1 C terminus”. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 22 (6): 476–84. (June 2015). doi:10.1038/nsmb.3018. PMC 4456216. PMID 25961797.

- ^ “The basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS orphan MOP3 forms transcriptionally active complexes with circadian and hypoxia factors”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95 (10): 5474–9. (May 1998). Bibcode: 1998PNAS...95.5474H. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.10.5474. PMC 20401. PMID 9576906.

- ^ “The basic helix-loop-helix-PAS protein MOP9 is a brain-specific heterodimeric partner of circadian and hypoxia factors”. The Journal of Neuroscience 20 (13): RC83. (July 2000). PMID 10864977.

外部リンク

[編集]- Human Human ARNTL genome location and ARNTL gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.UCSC Genome BrowserHuman ARNTL genome location and ARNTL gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.