利用者:ぎぶそん/作業場

|

ここはぎぶそんさんの利用者サンドボックスです。編集を試したり下書きを置いておいたりするための場所であり、百科事典の記事ではありません。ただし、公開の場ですので、許諾されていない文章の転載はご遠慮ください。

登録利用者は自分用の利用者サンドボックスを作成できます(サンドボックスを作成する、解説)。 その他のサンドボックス: 共用サンドボックス | モジュールサンドボックス 記事がある程度できあがったら、編集方針を確認して、新規ページを作成しましょう。 |

Template:Campaignbox Mexican-American War Template:Campaignbox Mexican-American wars

| アメリカ合衆国の歴史 |

|---|

|

| 年表 |

| 先コロンブス期 |

| 植民地時代 |

| 1776年-1789年 |

| 1789年-1849年 |

| 1849年-1865年 |

| 1865年-1918年 |

| 1918年-1945年 |

| 1945年-1964年 |

| 1964年-1980年 |

| 1980年-1991年 |

| 1991年-現在 |

| テーマ別 |

| 領土の変遷 |

| 領土獲得 |

| 外交史 |

| 軍事史 |

| 技術・産業史 |

| 経済史 |

| 文化史 |

| 政教分離史 |

| 南北戦争 |

| 南部史 |

| 西部開拓時代 |

| 公民権運動 (1896年-1954年) |

| 公民権運動 (1955年–1968年) |

| 女性史 |

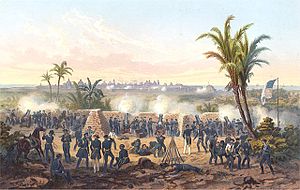

米墨戦争(w:Mexican–American War,Mexican War,U.S.–Mexican War, theInvasion of Mexico, U.S. Intervention,the United States War Against Mexico)は、アメリカ合衆国とメキシコ合衆国と間で1846年から1848年の間に戦われ、1836年のテキサス革命以降も自国領とみなしていたテキサス共和国を、アメリカ合衆国が自国領に編入したことをきっかけに始まった戦争である。 戦闘活動は1846年の春から1847年の秋まで1年半継続した。アメリカ軍は素早くニューメキシコとアルタ・カリフォルニアを占領し、さらに北東メキシコ(w:Northeastern Mexico) 、北西メキシコ(w:Northwest Mexico )両地域に侵攻した。その間に太平洋艦隊は封鎖を敢行し、バハカリフォルニア以南の複数の駐屯地を統制下に置いた。 もう一方のアメリカ陸軍は首都メキシコシティを攻略し、戦争はアメリカ合衆国の勝利で終わった。

「グアダルーペ・ヒダルゴ条約」はこの戦争以降の大きな結果である。すなわちメキシコに1500万ドルと引き換えにアルタカリフォルニアとニューメキシコをアメリカ合衆国への割譲である。 加えてアメリカ合衆国はメキシコ政府によるアメリカ合衆国国民への325万ドルの負債があると決めつけた。メキシコはテキサスの喪失とさらにリオグランデ川を国境に両国の国境とすることを容認した。

太平洋沿岸 へのアメリカ合衆国の領土の拡大 はジェームズ・ポーク大統領と彼が指導する民主党の悲願であった[5]。 しかし、この戦争はアメリカ合衆国では喧々諤々の議論の対象であり、ホイッグ党と反奴隷制団体は強く反対した。 重大なアメリカの負傷者と高い財政負担はまた批判された。戦争の後、アメリカ合衆国での奴隷制が問題化し、これが南北戦争へと至ることになる。1850年協定 には a brief respiteが付属している。

メキシコではこの戦争をprimera intervención estadounidense en México (アメリカ合衆国による第1次メキシコ介入), invasión estadounidense a México (アメリカ合衆国のメキシコ侵攻)そしてguerra del 47 (1847年戦争)と呼ぶ。

背景

[編集]1821年にスペインから独立を獲得すると、メキシコは内戦になるような国内の内輪もめに見舞われた。しかしテキサスの独立承認を拒否することに関しては相対的に連帯していた。 メキシコはアメリカ合衆国国務省にテキサスを併合すれば戦争になると恫喝した[6]。その間、ポーク大統領の「マニフェスト・ディスティニーの精神」は西方への拡大におけるアメリカ合衆国の国益に焦点が集まるようになっていた。 メキシコの軍事的、外交的能力は、独立獲得後、減退し、北部の国土の2分の1はコマンチ族, w:ApacheNavajoといった先住民に対して攻撃されやすい状態のまま残された。

先住民、とくにコマンチ族はメキシコの弱点に乗じて国土のおくふかく何百マイルの大規模な奇襲を起こした。家畜を盗み、これらを使用する、そして拡大しているテキサスとアメリカ合衆国の市場に供給するためである。 メキシコ人は、アメリカ人は奇襲を促進し支援しているを信じていた。 [7] 。

先住民の奇襲は数千ものの人々の死を残し、メキシコ北部は荒廃した。アメリカ合衆国軍は1846年にメキシコ北部に侵攻し、士気をくじかれた人々を見つけた。市民はアメリカ合衆国軍に抵抗することはほとんどなかった[8] (See: Comanche-Mexico Wars and Apache-Mexico Wars)。

カリフォルニア情勢

[編集]1842年、アメリカ合衆国のメキシコ公使ウェッデー・トンプソンは「メキシコは債務を解決するためにカリフォルニアを割譲するに違いないだろう」と示唆し「テキサスに関して、私はカリフォルニアと比べて微々たる価値しかないと思います。カリフォルニアは世界で最も豊かで、最も美しく、最も肥沃な土地です…アッパーカリフォルニア地域の獲得のよって私たちは太平洋に同様の興隆を有することになるでしょう…フランスとイングランドの両国はこの地に目を向けています」 ジョン・テイラー政権は「オレゴン境界紛争 」を解決する3者間協定を示唆し、サンフランシスコ港の割譲のための準備をした。 アバディーン卿は参加を拒否したが、イギリスははアメリカ合衆国のこの地のでの領土の獲得に反対はしなかった[9]。

イギリスのメキシコ公使リチャード・ペーケンハムは1841年にパーマストン卿を「アッパーカリフォルニアの広大な領域にイギリスの居住地を建設すること」を急かせるために手紙を書いた。手紙には「イギリスの植民地の建設のためにカリフォルニアよりも大きな自然の優位性を提供する地域は世界になく… 魅力的なすべての資力によって…カリフォルニアは、いったんメキシコへの帰属を止め、イギリス以外の列強の手に落ちることはないだろう…アメリカ合衆国の冒険的で山師どもはすでにこの考えの目標に向かっている」。しかし手紙がロンドンに届くまでに、ロバート・ピール政権は小英国政策を行使しようとしており、拡大の提案と紛争の可能性のを拒絶した [10][11]。

テキサス共和国

[編集]

1820年にミズーリの銀行家のw:Moses Austinはテキサスに広大な土地を与えられた。しかし移住者募集の計画を実現する前に彼は亡くなった。 彼の息子スティーヴン・F・オースティンはテキサスに300の家族を移住させることに成功した。彼らはアメリカ合衆国からテキサスへ確固とした移住の傾向を開始した。 オースティンの植民地はメキシコ政府に認められたいくつかの植民地の中では最も成功したものであった。 メキシコ政府はアングロサクソンの移住者をメキシコ人と略奪をするコマンチ族の緩衝になることをもくろんでいた。しかしアングロサクソンはれっきとしw:farmlandであり、彼らが効果的な緩衝になる西方地域よりもアメリカ・ルイジアナとのつながりをtradeしていた。

1829年、アメリカ合衆国の移民の大量の流入の結果、テキサス地域ではアングロサクソンは現地のスペイン系の数を上回った。 メキシコ政府は、財産税を課すこと、アメリカ合衆国からの輸入品の関税を引き上げること、奴隷制度を禁止することを決定した。この地域の移住者とメキシコの商人はテキサスの近くのメキシコに新たな移民の受け入れの要求を拒否した。しかしアメリカ合衆国からテキサスへの不法移民は継続した。

1834年アントニオ・ロペス・デ・サンタ・アナがメキシコ中央の独裁者になると、連邦制は廃止された。彼はテキサスの半独立を鎮圧することを決定した。コアウイラの独立を鎮圧したように (1824年、メキシコはテキサスとコアウイラを広大なコアウイラ・イ・テハス州に合併していた)。 ついにw:Stephen F. Austinはテクサン(テキサス人)に武器を取るように命令した。テキサスは1836年にメキシコからの独立を宣言した。サンタ・アナがアラモでテクサス人を破った後にである、彼はサム・ヒューストン率いるテクサス軍に敗北し、サン・ジャシントの戦いで捕虜となり、テキサス独立賞にの条約に署名した[12]。

テキサスは独立した共和国としてその地位を確定させ、イギリス、フランスおよびアメリカ合衆国から公式な独立承認を受けた。これらの国々はメキシコにテキサスを再征服しないように助言した。

テクサンのほとんどがアメリカ合衆国と一緒になることを望んだ。しかしテクサスの併合はアメリカ合衆国議会で議論となった。そこではホイッグ党は大いに反対した。1845年テキサスはアメリカ合衆国議会による併合の申し入れに合意した。テキサスは1845年12月29日アメリカ合衆国28番目の州となる[12]。

戦争の発端

[編集]独立国としてのテキサスの国境は画定していなかった。テキサス共和国は「ヴェラスコ条約」に基づきリオ・グランデ川以北を主張していたが、メキシコは、ヌエセス川を国境として主張し、これらテキサス側の主張を妥当なものとして受諾するのを拒否した。 リオグランデ川国境についての記録は、上院で併合条約が否決されたのち、抜け道を保証するのを助けるためのアメリカ合衆国議会の併合決議によって削除された。 ポーク大統領はリオグランデ川国境を主張し、これがメキシコとの論争を引き起こした [13]。

1845年、ポークはザカリー・テイラー将軍をテキサスに派遣し10月までに3500人のアメリカ人がヌエセス川に配置された。これはテキサスをメキシコからの侵略に守るための措置であった。 ポークは国境を守りたかった。そして太平洋沿岸への大陸をはっきりと切望したのであった。 ポークはもしメキシコが宣戦布告したとき、「w:Pacific Squadron 」にカリフォルニアの港を制圧するよう指示を出した。 while staying on good terms with the inhabitants. 同時に、彼はアルタカリフォルニアの領事トーマス・ラーキンに手紙を書いた。アメリカ合衆国のカリフォルニアの野心を否定しつつも、カリフォルニアのメキシコからの独立あるいはアメリカ合衆国への自発的な接近への支援を申し出でる一方で、イギリスとフランスがカリフォルニア支配を継承することには反対した。 [13]

オレゴンの向こうでのもう一つの戦争はイギリスを撃退させたことで幕を切った。ポーク大統領は、オレゴン地域を分割する「オレゴン条約」に署名した。ポーク大統領は北部の拡張よりも南部の拡張を優先していると感じている北部の民主党員は怒っていた。

1845年から46年の冬に、the federally commissioned explorer ジョン・C・フレモントと武装集団がカリフォルニアに姿を現した。 メキシコの知事とラーキンに告げた後、彼は単にオレゴンへの途上の食料を購入した。その代わりに彼は、カリフォルニアの人の住む地域に入り、彼の母のために沿岸部に家を求めてサンタ・クルスとサリナス渓谷を訪れた。 [14] メキシコ当局は彼に退避するよう警告した。フレモントはガヴィラン・ピーク砦を造営することで応じ、この砦にアメリカ合衆国国旗を掲揚した。ラーキンは彼の行動は逆効果だとう言葉をおくった。

フレモントは3月にカリフォルニアを離れたが、再び戻り、ソノマに カリフォルニア共和国を建国することになる「熊の旗の乱」を支援した。ここでは多くのアメリカ人移住者が「テキサス・ゲーム」に興じはじめ、メキシコからのカリフォルニアの独立を宣言した。

1845年11月10日[15]ポーク大統領はジョン・スライデルを秘密代表として、2500万ドル(いまの$880,384,615に相当)でリオグランデ川のテキサスの国境とメキシコのアルタ・カリフォルニア州とサンタ・フェ・デヌエヴォ・メキシコ州を購入する申し出とともにメキシコ派遣した。アメリカ合衆国の拡張はカリフォルニアにおけるイギリスの野心をくじくとともに太平洋岸の港湾を獲得するものであった。

ポークはスライデルに300万ドル($106 million today)をアメリカ合衆国公民にメキシコ独立戦争よって生じた損害のために貸し付けることを許すことを委任していた[16]。そして2地域と引き換えに2500万ドル、3000万ドル($880 million to $1,056 million today) を支払うことも許可していた.[17] 。 メキシコは関心をもたれなかったし、あるいは交渉できなかった。 1846年だけで、大統領は4度変わり、国防大臣は6度変わり、財務大臣は16回変わった。 [18] しかしメキシコの世論とすべての政治的派閥は、領土をアメリカ合衆国に売ることは国民の名誉を曇らせるであろうことで一致していた。 [19] ホセ・ホアキン・デ・ヘレラ大統領を含む、アメリカ合衆国との紛争への道に反対するメキシコ人は裏切り者と見られた。 [20] 人気取りの新聞に支持された、反デ・ヘレラの軍部はメキシコシティのスライデルの存在を屈辱と考えた。 デ・ヘレラはスライデルが平和裏にテキサス併合問題を解決することを受理を検討したとき、彼は反逆者として非難され失脚した。 w:Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga将軍の下での一層ナショナリスティックな政府が権力を握ったのち、同政府は公にメキシコのテキサスへの主張を再確認した。 [20] 。スライデルはメキシコは「懲罰される」だろうと確信し、アメリカ合衆国本国に帰国した。 [21]

the Nueces Stripでの紛争

[編集]ポーク大統領はテイラー将軍とその軍にリオグランデ川へと南下し、メキシコ人が領有権を主張する領域に入るよう命令した。 メキシコはリオグランデ川より240㎞ほど北にあるヌエセス川を北の国境と主張していた。 アメリカ合衆国は1836年の「ヴェラスコ条約」引用して、リオグランデ川を国境と主張した。 メキシコは条約を拒否し、交渉を拒絶してきた。メキシコはテキサス全域を主張した[22]。 テイラーはメキシコのヌエセス川からの撤退の要求を無視した。 彼は、リオグランデ川の沿岸、w:Matamoros, Tamaulipas市の対面に急ごしらえの砦を建設した[23] w:Mariano Arista指揮下のメキシコ軍は戦争の準備をした。1846年4月25日、2000のメキシコの騎兵部隊は70人のアメリカ合衆国パトロールを攻撃した。このパトロールは隊はヌエセス川以南、リオグランデ川以北の係争地に派遣されていた。 w:Thornton Affairにおいて、メキシコ騎兵隊はパトロール隊を追いかけ16人のアメリカ合衆国兵士を殺害した [24]。

宣戦布告

[編集]

ポークはThornton Affairの報せを受けた。加えてメキシコ政府がスライデルを拒絶した報せも受け取った。ポークはThornton Affairが「戦争の大義(w:casus belli) 」の構成要素になると信じていた[25] 。 1846年5月11日、彼の合衆国議会での演説は「メキシコはアメリカ合衆国との国境を通過し、我が国を侵略し、アメリカ合衆国の大地をアメリカ合衆国国民の血で濡らした」と公に述べたものとなった。 [26][27] 5月13日議会は、南部の民主党の支持を受けて宣戦布告を可決した。 67人のホイッグ党の議員は、奴隷制改正をカギに戦争反対に投票した[28] 。しかし最後のパッセージに14人だけのホイッグ党員が反対を投じた[28] そこにはジョン・クインシー・アダムズも含まれいた・ 1846年5月13日、ほんのわずかの議論ののち議会はメキシコに宣戦布告した 5月23日のパレデス大統領の公約の方針は宣戦布告を時に考慮しているというものであったが、7月7日メキシコ議会もアメリカ合衆国に宣戦布告した。

アントニオ・ロペス・デ・サンタ・アナ

[編集]アメリカ合衆国がメキシコに宣戦布告したとき、アントニオ・ロペス・デ・サンタ・アナはメキシコシティに自分は大統領への意欲はもはやないが、メキシコへの外国の侵略に率先して戦うために経験を使う意欲はあると書き送った。 Valentín Gómez Farías大統領は申し出を受諾しサンタ・アナの返り咲きを許さねばならないほど窮していた。 そうこうしているうちに、サンタ・アナはひそかにアメリカ合衆国代表と取引をしていた。もし自分がアメリカ合衆国海軍の海上封鎖をすり抜けてメキシコへ帰ることが許されたなら、アメリカ合衆国と係争している地域を手ごろな値段で売却することにひと肌に脱ぐことを誓約すると[29]。 陸軍の長としてメキシコに帰還すると、サンタ・アナは両方の合意を反故にした。サンタ・アナは大統領に返り咲き、アメリカ合衆国との戦うことへの挑戦には失敗した。

戦争反対論

[編集]Template:Events leading to US Civil War

アメリカ合衆国では、ますます 派閥競争によって分断され、戦争は党派の問題であり南北戦争の原因において根源的要素となった。 北部と南部の最多数のホイッグ党員が反対した。 [30] most Democrats supported it.[31] 南部の民主党員は、「マニフェスト・ディスティニー」によって活気づき、奴隷制の地域を南部に加え、北部のより速い成長によって数が増えることを避けることを希望して支援した。 「民主党レヴュー(the Democratic Review)」の編集者のw:John L. O’Sullivanは「私たちの毎年増殖する何百万人の自由な発展のために州で区分けされている大陸に広がるためのマニフェストディニーにそれはならなければならない。その文脈においてこのフレーズを造語した [32]

Northern antislavery elements feared the rise of a Slave Power; Whigs generally wanted to strengthen the economy with industrialization, not expand it with more land. Democrats wanted more land; northern Democrats were attracted by the possibilities in the far northwest. Joshua Giddings led a group of dissenters in Washington D.C. He called the war with Mexico “an aggressive, unholy, and unjust war,” and voted against supplying soldiers and weapons. He said:

In the murder of Mexicans upon their own soil, or in robbing them of their country, I can take no part either now or hereafter. The guilt of these crimes must rest on others. I will not participate in them.[33]

Fellow Whig Abraham Lincoln contested the causes for the war and demanded to know exactly where Thornton had been attacked and American blood shed. “Show me the spot,” he demanded. Whig leader Robert Toombs of Georgia declared:

This war is nondescript.... We charge the President with usurping the war-making power ... with seizing a country ... which had been for centuries, and was then in the possession of the Mexicans.... Let us put a check upon this lust of dominion. We had territory enough, Heaven knew.[34]

Northern abolitionists attacked the war as an attempt by slave-owners to strengthen the grip of slavery and thus ensure their continued influence in the federal government. Acting on his convictions, Henry David Thoreau was jailed for his refusal to pay taxes to support the war, and penned his famous essay Civil Disobedience.

Former president John Quincy Adams also expressed his belief that the war was primarily an effort to expand slavery in a speech he gave before the House on May 25, 1836.[35] In response to such concerns, Democratic Congressman David Wilmot introduced the Wilmot Proviso, which aimed to prohibit slavery in new territory acquired from Mexico. Wilmot’s proposal did not pass Congress, but it spurred further hostility between the factions.

防衛戦争

[編集]メキシコ軍のリオグランデ川以北の係争地での行動がアメリカ合衆国の大地への攻撃を継続しているという断言のほかに、戦争での主張はニューメキシコとカリフォルニアを薄弱な統治の名目だけの領土とみなすようになった。 彼らは領土を実際に移住せず統治せずそして防衛していない辺境の地に見えた。where there was any at allこの地域の非先住民は実際にこの地の多数のアメリカ人の集団にによって代表されていた。 さらに、この領域はアメリカ合衆国の北米大陸でのライバルのイギリスによる差し迫った獲得の脅威のもとにあると恐れられていた。

ポーク大統領は1847年12月7日の議会でのThird Annual Messageで議論を繰り返した[36]。 そこで、彼は真剣に彼の紛争の起源における行政上の位置づけ 、アメリカ合衆国が敵対的行為を避けてきた併合のこと、そして宣戦布告の正当性を詳細に説明した。 He also elaborated upon the many outstanding financial claims by American citizens against Mexico and argued that, in view of the country’s insolvency, the cession of some large portion of its northern territories was the only indemnity realistically available as compensation. This helped to rally congressional Democrats to his side, ensuring passage of his war measures and bolstering support for the war in the U.S.

戦闘のはじまり

[編集]The Siege of Fort Texas began on May 3. Mexican artillery at Matamoros opened fire on Fort Texas, which replied with its own guns. The bombardment continued for 160 hours[37] and expanded as Mexican forces gradually surrounded the fort. Thirteen U.S. soldiers were injured during the bombardment, and two were killed.[37] Among the dead was Jacob Brown, after whom the fort was later named.[38]

On May 8, Zachary Taylor and 2,400 troops arrived to relieve the fort.[39] However, Arista rushed north and intercepted him with a force of 3,400 at Palo Alto. The Americans employed "flying artillery", the American term for horse artillery, a type of mobile light artillery that was mounted on horse carriages with the entire crew riding horses into battle. It had a devastating effect on the Mexican army. The Mexicans replied with cavalry skirmishes and their own artillery. The U.S. flying artillery somewhat demoralized the Mexican side, and seeking terrain more to their advantage, the Mexicans retreated to the far side of a dry riverbed (resaca) during the night. It provided a natural fortification, but during the retreat, Mexican troops were scattered, making communication difficult.[37]

During the Battle of Resaca de la Palma the next day, the two sides engaged in fierce hand to hand combat. The U.S. cavalry managed to capture the Mexican artillery, causing the Mexican side to retreat—a retreat that turned into a rout.[37] Fighting on unfamiliar terrain, his troops fleeing in retreat, Arista found it impossible to rally his forces. Mexican casualties were heavy, and the Mexicans were forced to abandon their artillery and baggage. Fort Brown inflicted additional casualties as the withdrawing troops passed by the fort. Many Mexican soldiers drowned trying to swim across the Rio Grande.

戦闘の指揮

[編集]After the declaration of war on May 13, 1846, U.S. forces invaded Mexican territory on two main fronts. The U.S. War Department sent a U.S. cavalry force under Stephen W. Kearny to invade western Mexico from Jefferson Barracks and Fort Leavenworth, reinforced by a Pacific fleet under John D. Sloat. This was done primarily because of concerns that Britain might also try to seize the area. Two more forces, one under John E. Wool and the other under Taylor, were ordered to occupy Mexico as far south as the city of Monterrey.

カリフォルニア遠征

[編集]- [[{{{campaign-name}}}]]

-

- [[{{{battle1}}}]]

Although the U.S. declared war against Mexico on May 13, 1846, it took over a month (until the middle of June 1846) for definite word of war to get to California. American consul Thomas O. Larkin, stationed in Monterey, heard rumors of war and tried to maintain the peace between the States and the small Mexican military garrison commanded by José Castro. U.S. Army captain John C. Frémont, with about 60 well-armed men, had entered California in December 1845, and was slowly marching to Oregon when he received word that war between Mexico and the U.S. was imminent. On June 15, 1846, some thirty settlers, mostly American citizens, staged a revolt and seized the small Mexican garrison in Sonoma. The U.S. Army, led by Frémont, took over on June 23. Commodore John Drake Sloat, upon hearing of imminent war and the revolt in Sonoma, ordered his forces to occupy Monterey, the capital, on July 7 and raise the flag of the U.S.; San Francisco, then called Yerba Buena, was occupied on July 9. On July 15, Sloat transferred his command to Commodore Robert F. Stockton, a much more aggressive leader, who put Frémont's forces under his orders. On July 19, Frémont's "California Battalion" swelled to about 160 additional men from newly arrived settlers near Sacramento, and he entered Monterey in a joint operation with some of Stockton's sailors and marines. The U.S. forces easily took over northern California; within days they controlled San Francisco, Sonoma, and Sacramento.

Mexican General José Castro and Governor Pío Pico fled southward from Alta California (the present-day American state of California). When Stockton's forces, sailing southward to San Diego, stopped in San Pedro, he sent 50 U.S. Marines ashore; this force entered Los Angeles unresisted on August 13, 1846. With the success of this so-called "Siege of Los Angeles", the nearly bloodless conquest of California seemed complete.

Stockton, however, left too small a force in Los Angeles; the Californios under the leadership of José María Flores, acting on their own and without help from Mexico, forced the American garrison to retreat, late in September. The rancho vaqueros who had banded together to defend their land fought as Californio lancers; they were a force the Americans had not anticipated. More than 300 American reinforcements, sent by Stockton and led by Captain William Mervine, U.S.N., were repulsed in the Battle of Dominguez Rancho, fought from October 7 through 9, 1846, near San Pedro. Fourteen American Marines were killed.

Meanwhile, General Stephen W. Kearny, with a squadron of 139 dragoons that he had led on a grueling march across New Mexico, Arizona, and the Sonoran Desert, finally reached California on December 6, 1846, and fought in a small battle with Californio lancers at the Battle of San Pasqual near San Diego, California, where 22 of Kearny's troops were killed. Kearny's command was bloodied and in poor condition but pushed on until they had to establish a defensive position on "Mule" Hill near present-day Escondido. The Californios besieged the dragoons for four days until Commodore Stockton's relief force arrived.

The resupplied, combined American force marched north from San Diego on December 29 and entered the Los Angeles area on January 8, 1847,[40] linking up with Frémont's men there. American forces totaling 607 soldiers and Marines fought and defeated a Californio force of about 300 men under the command of Captain-general Flores in the decisive Battle of Rio San Gabriel.[41] The next day, January 9, 1847, the Americans fought and won the Battle of La Mesa. On January 12, the last significant body of Californios surrendered to U.S. forces. That marked the end of armed resistance in California, and the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed the next day, on January 13, 1847.

太平洋沿岸遠征

[編集]

USS Independence assisted in the blockade of the Mexican Pacific coast, capturing the Mexican ship Correo and a launch on May 16, 1847. She supported the capture of Guaymas, Sonora, on October 19, 1847, and landed bluejackets and Marines to occupy Mazatlán, Sinaloa, on November 11, 1847. After upper California was secure, most of the Pacific Squadron proceeded down the California coast, capturing all major Baja California cities and capturing or destroying nearly all Mexican vessels in the Gulf of California. Other ports, not on the peninsula, were taken as well. The objective of the Pacific Coast Campaign was to capture Mazatlán, a major supply base for Mexican forces. Numerous Mexican ships were also captured by this squadron, with the USS Cyane given credit for 18 ships captured and numerous destroyed.[42]

Entering the Gulf of California, Independence, Congress, and Cyane seized La Paz, then captured and burned the small Mexican fleet at Guaymas. Within a month, they cleared the Gulf of hostile ships, destroying or capturing 30 vessels. Later, their sailors and marines captured the port of Mazatlán on November 11, 1847. A Mexican campaign under Manuel Pineda to retake the various captured ports resulted in several small clashes (Battle of Mulege, Battle of La Paz, Battle of San José del Cabo) and two sieges (Siege of La Paz, Siege of San José del Cabo) in which the Pacific Squadron ships provided artillery support. U.S. garrisons remained in control of the ports.

Following reinforcement, Lt. Col. Henry S. Burton marched out. His forces rescued captured Americans, captured Pineda, and, on March 31, defeated and dispersed remaining Mexican forces at the Skirmish of Todos Santos, unaware that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had been signed in February 1848. When the American garrisons were evacuated to Monterey following the treaty, many Mexicans went with them: those who had supported the American cause and had thought Lower California would also be annexed like Upper California.

北東メキシコ

[編集]The defeats at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma caused political turmoil in Mexico, turmoil which Antonio López de Santa Anna used to revive his political career and return from self-imposed exile in Cuba in mid-August 1846.[43] He promised the U.S. that if allowed to pass through the blockade, he would negotiate a peaceful conclusion to the war and sell the New Mexico and Alta California territories to the U.S.[44] Once Santa Anna arrived in Mexico City, however, he reneged and offered his services to the Mexican government. Then, after being appointed commanding general, he reneged again and seized the presidency.

Led by Taylor, 2,300 U.S. troops crossed the Rio Grande (Rio Bravo) after some initial difficulties in obtaining river transport. His soldiers occupied the city of Matamoros, then Camargo (where the soldiery suffered the first of many problems with disease) and then proceeded south and besieged the city of Monterrey. The hard-fought Battle of Monterrey resulted in serious losses on both sides. The American light artillery was ineffective against the stone fortifications of the city. The Mexican forces were under General Pedro de Ampudia and repulsed Taylor's best infantry division at Fort Teneria.[45]

American soldiers, including many West Pointers, had never engaged in urban warfare before and they marched straight down the open streets, where they were annihilated by Mexican defenders well-hidden in Monterrey's thick adobe homes.[45] Two days later, they changed their urban warfare tactics. Texan soldiers had fought in a Mexican city before and advised Taylor's generals that the Americans needed to "mouse hole" through the city's homes. In other words, they needed to punch holes in the side or roofs of the homes and fight hand to hand inside the structures. This method proved successful.[46] Eventually, these actions drove and trapped Ampudia's men into the city's central plaza, where howitzer shelling forced Ampudia to negotiate. Taylor agreed to allow the Mexican Army to evacuate and to an eight-week armistice in return for the surrender of the city. Under pressure from Washington, Taylor broke the armistice and occupied the city of Saltillo, southwest of Monterrey. Santa Anna blamed the loss of Monterrey and Saltillo on Ampudia and demoted him to command a small artillery battalion.

On February 22, 1847, Santa Anna personally marched north to fight Taylor with 20,000 men. Taylor, with 4,600 men, had entrenched at a mountain pass called Buena Vista. Santa Anna suffered desertions on the way north and arrived with 15,000 men in a tired state. He demanded and was refused surrender of the U.S. Army; he attacked the next morning. Santa Anna flanked the U.S. positions by sending his cavalry and some of his infantry up the steep terrain that made up one side of the pass, while a division of infantry attacked frontally along the road leading to Buena Vista. Furious fighting ensued, during which the U.S troops were nearly routed, but managed to cling to their entrenched position. The Mexicans had inflicted considerable losses but Santa Anna had gotten word of upheaval in Mexico City, so he withdrew that night, leaving Taylor in control of part of Northern Mexico.

Polk distrusted Taylor, whom he felt had shown incompetence in the Battle of Monterrey by agreeing to the armistice, and may have considered him a political rival for the White House. Taylor later used the Battle of Buena Vista as the centerpiece of his successful 1848 presidential campaign.

北西メキシコ

[編集]On March 1, 1847, Alexander W. Doniphan occupied Chihuahua City. He found the inhabitants much less willing to accept the American conquest than the New Mexicans. British consul John Potts did not want to let Doniphan search Governor Trias's mansion, and unsuccessfully asserted it was under British protection. American merchants in Chihuahua wanted the American force to stay in order to protect their business. Gilpin advocated a march on Mexico City and convinced a majority of officers, but Doniphan subverted this plan. Then in late April, Taylor ordered the First Missouri Mounted Volunteers to leave Chihuahua and join him at Saltillo. The American merchants either followed or returned to Santa Fe. Along the way, the townspeople of Parras enlisted Doniphan's aid against an Indian raiding party that had taken children, horses, mules, and money.[47]

The civilian population of northern Mexico offered little resistance to the American invasion, possibly because the country had already been devastated by Comanche and Apache Indian raids. Josiah Gregg, who was with the American army in northern Mexico, said that “the whole country from New Mexico to the borders of Durango is almost entirely depopulated. The haciendas and ranchos have been mostly abandoned, and the people chiefly confined to the towns and cities.”[48]

タバスコ

[編集]第1次タバスコの戦い

[編集]Commodore Matthew C. Perry led a detachment of seven vessels along the southern coast of Tabasco state. Perry arrived at the Tabasco River (now known as the Grijalva River) on October 22, 1846, and seized the town Port of Frontera along with two of their ships. Leaving a small garrison, he advanced with his troops towards the town of San Juan Bautista (Villahermosa today). Perry arrived in the city of San Juan Bautista on October 25, seizing five Mexican vessels. Colonel Juan Bautista Traconis, Tabasco Departmental commander at that time, set up barricades inside the buildings. Perry realized that the bombing of the city would be the only option to drive out the Mexican Army, and avoiding damage to the merchants of the city, withdrew its forces preparing them for the next day.

On the morning of October 26, Perry's fleet prepared to start the attack on the city, the Mexican forces began firing at the American fleet. The U.S. bombing began to yield the square, so that the fire continued until evening. Before taking the square, Perry decided to leave and return to the port of Frontera, where he established a naval blockade to prevent supplies of food and military supplies from reaching the state capital.

第2次タバスコの戦い

[編集]On June 13, 1847, Matthew C. Perry assembled the Mosquito Fleet and began moving towards the Grijalva River, towing 47 boats that carried a landing force of 1,173. On June 15, 12 miles (19 km) below San Juan Bautista, the fleet ran through an ambush with little difficulty. Again at an "S" curve in the river known as the "Devil's Bend", Perry encountered Mexican fire from a river fortification known as the Colmena redoubt, but the fleet's heavy naval guns quickly dispersed the Mexican force.

On June 16, Perry arrived to San Juan Bautista and commenced bombing the city. The attack included two ships that sailed past the fort and began shelling it from the rear. David D. Porter led 60 sailors ashore and seized the fort, raising the U.S. flag over the works. Perry and the landing force arrived and took control of the city around 2 p.m.

U.S. press and popular war enthusiasm

[編集]During the war, inventions such as the telegraph created new means of communication that updated people with the latest news from the reporters, who were usually on the scene. With more than a decade’s experience reporting urban crime, the “penny press” realized the public's voracious need for astounding war news. This was the first time in American history that accounts by journalists, instead of opinions of politicians, caused great influence in shaping people’s minds and attitudes toward a war.

By getting constant reports from the battlefield, Americans became emotionally united as a community. News about the war always caused extraordinary popular excitement. In the spring of 1846, news about Zachary Taylor's victory at Palo Alto brought up a large crowd that met in a cotton textile town of Lowell, Massachusetts. New York celebrated the twin victories at Veracruz and Buena Vista in May 1847. Among fireworks and illuminations, they had a “grand procession” of about 400,000 people. Generals Taylor and Scott became heroes for their people and later became presidential candidates.

Desertion

[編集]

Desertion was a major problem for the Mexican army, depleting forces on the eve of battle. Most soldiers were peasants who had a loyalty to their village and family, but not to the generals who had conscripted them. Often hungry and ill, under-equipped, only partially trained, and never well paid, the soldiers were held in contempt by their officers and had little reason to fight the Americans. Looking for their opportunity, many slipped away from camp to find their way back to their home village.[49]

The desertion rate in the U.S. army was 8.3% (9,200 out of 111,000), compared to 12.7% during the War of 1812 and usual peacetime rates of about 14.8% per year.[50] Many men deserted to join another U.S. unit and get a second enlistment bonus. Some deserted because of the miserable conditions in camp. It has been suggested that others used the army to get free transportation to California, where they deserted to join the gold rush;[51] this, however, is unlikely as gold was only discovered in California on January 24, 1848, less than two weeks before the war concluded. By the time word reached the eastern U.S. that gold had been discovered, word also reached it that the war was over.

Several hundred U.S. deserters went over to the Mexican side. Nearly all were recent immigrants from Europe with weak ties to the U.S.; the most famous group was the Saint Patrick's Battalion, about half of whom were Catholics from Ireland. The Mexicans issued broadsides and leaflets enticing U.S. soldiers with promises of money, land bounties, and officers' commissions. Mexican guerrillas shadowed the U.S. Army and captured men who took unauthorized leave or fell out of the ranks. The guerrillas coerced these men to join the Mexican ranks. The generous promises proved illusory for most deserters, who risked being executed if captured by U.S. forces. About 50 of the San Patricios were tried and hanged following their capture at Churubusco in August 1847.[51]

スコットの首都遠征

[編集]- [[{{{campaign-name}}}]]

-

- [[{{{battle1}}}]]

上陸とヴェラクルス包囲戦

[編集]

Rather than reinforce Taylor's army for a continued advance, President Polk sent a second army under General Winfield Scott, which was transported to the port of Veracruz by sea, to begin an invasion of the Mexican heartland. On March 9, 1847, Scott performed the first major amphibious landing in U.S. history in preparation for the Siege of Veracruz. A group of 12,000 volunteer and regular soldiers successfully offloaded supplies, weapons, and horses near the walled city using specially designed landing craft. Included in the invading force were Robert E. Lee, George Meade, Ulysses S. Grant, James Longstreet, and Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson.

The city was defended by Mexican General Juan Morales with 3,400 men. Mortars and naval guns under Commodore Matthew C. Perry were used to reduce the city walls and harass defenders. The city replied the best it could with its own artillery. The effect of the extended barrage destroyed the will of the Mexican side to fight against a numerically superior force, and they surrendered the city after 12 days under siege. U.S. troops suffered 80 casualties, while the Mexican side had around 180 killed and wounded, about half of whom were civilian. During the siege, the U.S. side began to fall victim to yellow fever.

プエブラ進軍

[編集]Scott then marched westward toward Mexico City with 8,500 healthy troops, while Santa Anna set up a defensive position in a canyon around the main road at the halfway mark to Mexico City, near the hamlet of Cerro Gordo. Santa Anna had entrenched with 12,000 troops and artillery that were trained on the road, along which he expected Scott to appear. However, Scott had sent 2,600 mounted dragoons ahead; the Mexican artillery prematurely fired on them and therefore revealed their positions.

Instead of taking the main road, Scott's troops trekked through the rough terrain to the north, setting up his artillery on the high ground and quietly flanking the Mexicans. Although by then aware of the positions of U.S. troops, Santa Anna and his troops were unprepared for the onslaught that followed. The Mexican army was routed. The U.S. Army suffered 400 casualties, while the Mexicans suffered over 1,000 casualties and 3,000 were taken prisoner. In August 1847, Captain Kirby Smith, of Scott's 3rd Infantry, reflected on the resistance of the Mexican army:

They can do nothing and their continued defeats should convince them of it. They have lost six great battles; we have captured six hundred and eight cannon, nearly one hundred thousand stands of arms, made twenty thousand prisoners, have the greatest portion of their country and are fast advancing on their Capital which must be ours,—yet they refuse to treat [i.e., negotiate terms]![52]

プエブラでの足止め

[編集]In May, Scott pushed on to Puebla, the second largest city in Mexico. Because of the citizens' hostility to Santa Anna, the city capitulated without resistance on May 1. During the following months Scott gathered supplies and reinforcements at Puebla and sent back units whose enlistments had expired. Scott also made strong efforts to keep his troops disciplined and treat the Mexican people under occupation justly, so as to prevent a popular rising against his army.

首都進撃と攻略

[編集]With guerrillas harassing his line of communications back to Vera Cruz, Scott decided not to weaken his army to defend the city but, leaving only a garrison at Puebla to protect the sick and injured recovering there, advanced on Mexico City on August 7 with his remaining force. The capital was laid open in a series of battles around the right flank of the city defenses, at the Battle of Contreras and Churubusco. culminating in the Battle of Chapultepec. Fighting halted for a time when an armistice and peace negotiations followed the Battle of Churubusco, until they broke down, on September 6, 1847. With the subsequent battles of Molino del Rey and of Chapultepec, and the storming of the city gates, the capital was occupied. Winfield Scott became an American national hero after his victories in this campaign of the Mexican–American War, and later became military governor of occupied Mexico City.

サンタ・アナの最後の遠征

[編集]In late September 1847, Santa Anna made one last attempt to defeat the Americans, by cutting them off from the coast. General Joaquín Rea began the Siege of Puebla, soon joined by Santa Anna, but they failed to take it before the approach of a relief column from Vera Cruz under Brig. Gen. Joseph Lane prompted Santa Anna to stop him. Puebla was relieved by Gen. Lane October 12, 1847, following his defeat of Santa Anna at the Battle of Huamantla on October 9, 1847. The battle was Santa Anna's last. Following the defeat, the new Mexican government led by Manuel de la Peña y Peña asked Santa Anna to turn over command of the army to General José Joaquín de Herrera.

反ゲリラ戦

[編集]Following his capture and securing of the capital, General Scott sent about a quarter of his strength to secure his line of communications to Vera Cruz from the Light Corps of General Joaquín Rea and other Mexican guerilla forces that had been harassing it since May. He strengthened the garrison of Puebla and by November had added a 1200 man garrison at Jalapa, established 750-man posts along the National Road at Perote, Puente Nacional, Rio Frio, and at a bridge over the San Juan River.[53] He had also detailed an antiguerrilla brigade under Brig. Gen. Joseph Lane to carry the war to the Light Corps and other guerillas. He ordered that convoys would travel with at least 1,300-man escorts. Despite some victories by General Lane over the Light Corps at Atlixco (October 18, 1847) and at Izucar de Matamoros (November 23, 1847) and over the guerrillas of Padre Jaruta at Zacualtipan (February 25, 1848), guerrilla raids on the American line of communications continued until August but after the two governments concluded a truce to await ratification of the peace treaty, on March 6, 1848, formal hostilities ceased.[54]

グアダルーペ・ヒダルゴ条約Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

[編集]

Outnumbered militarily and with many of its large cities occupied, Mexico could not defend itself; the country was also faced with many internal divisions, inclucing the Caste War of Yucatán. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, by American diplomat Nicholas Trist and Mexican plenipotentiary representatives Luis G. Cuevas, Bernardo Couto, and Miguel Atristain, ended the war. The treaty gave the U.S. undisputed control of Texas, established the U.S.-Mexican border of the Rio Grande, and ceded to the United States the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. In return, Mexico received US $18,250,000[55] ($642,680,769 today) – less than half the amount the U.S. had attempted to offer Mexico for the land before the opening of hostilities[56] – and the U.S. agreed to assume $3.25 million ($114,450,000 today) in debts that the Mexican government owed to U.S. citizens.[16]

The acquisition was a source of controversy then, especially among U.S. politicians who had opposed the war from the start. A leading antiwar U.S. newspaper, the Whig Intelligencer, sardonically concluded that "We take nothing by conquest .... Thank God."[57][58]

Jefferson Davis introduced an amendment giving the U.S. most of northeastern Mexico, which failed 44–11. It was supported by both senators from Texas (Sam Houston and Thomas Jefferson Rusk), Daniel S. Dickinson of New York, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, Edward A. Hannegan of Indiana, and one each from Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri, and Tennessee. Most of the leaders of the Democratic party – Thomas Hart Benton, John C. Calhoun, Herschel V. Johnson, Lewis Cass, James Murray Mason of Virginia, and Ambrose Hundley Sevier – were opposed.[59] An amendment by Whig Senator George Edmund Badger of North Carolina to exclude New Mexico and California lost 35–15, with three Southern Whigs voting with the Democrats. Daniel Webster was bitter that four New England senators made deciding votes for acquiring the new territories.

The acquired lands west of the Rio Grande are traditionally called the Mexican Cession in the U.S., as opposed to the Texas Annexation two years earlier, though division of New Mexico down the middle at the Rio Grande never had any basis either in control or Mexican boundaries. Mexico never recognized the independence of Texas[60] prior to the war, and did not cede its claim to territory north of the Rio Grande or Gila River until this treaty.

Prior to ratifying the treaty, the U.S. Senate made two modifications: changing the wording of Article IX (which guaranteed Mexicans living in the purchased territories the right to become U.S. citizens) and striking out Article X (which conceded the legitimacy of land grants made by the Mexican government). On May 26, 1848, when the two countries exchanged ratifications of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, they further agreed to a three-article protocol (known as the Protocol of Querétaro) to explain the amendments. The first article claimed that the original Article IX of the treaty, although replaced by Article III of the Treaty of Louisiana, would still confer the rights delineated in Article IX. The second article confirmed the legitimacy of land grants under Mexican law.[61] The protocol was signed in the city of Querétaro by A. H. Sevier, Nathan Clifford, and Luis de la Rosa.[61]

Article XI offered a potential benefit to Mexico, in that the US pledged to suppress the Comanche and Apache raids that had ravaged northern Mexico and pay restitutions to the victims of raids it could not prevent.[62] However, the Indian raids did not cease for several decades after the treaty, although a cholera epidemic reduced the numbers of the Comanche in 1849.[63] Robert Letcher, U.S. Minister to Mexico in 1850, was certain "that miserable 11th article" would lead to the financial ruin of the US if it could not be released from its obligations.[64] The US was released from all obligations of Article XI five years later by Article II of the Gadsden Purchase of 1853.[65]

Results

[編集]

Altered territories

[編集]Mexican territory, prior to the secession of Texas, comprised almost 1,700,000 sq mi (4,400,000 km2), which was reduced to just under 800,000 by 1848. Another 32,000 were sold to the U.S. in the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, for a total reduction of more than 55%, or 900,000 square miles.[66]

The annexed territories, although comparable in size to Western Europe, were sparsely populated. The lands contained about 14,000 people in Alta California and fewer than 60,000 in Nuevo México,[67][68] as well as large Native American nations such as the Navajo, Hopi, and dozens of others. A few relocated further south in Mexico. The great majority chose to remain in the U.S. and later became U.S. citizens.

The American settlers surging into the newly conquered Southwest were openly contemptuous of Mexican law (a civil law system based on the law of Spain) as alien and inferior and threw it out the window by enacting reception statutes at the first available opportunity. However, they recognized the value of a few aspects of Mexican law and carried them over into their new legal systems. For example, most of the southwestern states adopted community property marital property systems.

The home front

[編集]In much of the U.S., victory and the acquisition of new land brought a surge of patriotism. Victory seemed to fulfill Democrats' belief in their country's Manifest Destiny. While Whig Ralph Waldo Emerson rejected war "as a means of achieving America's destiny," he accepted that "most of the great results of history are brought about by discreditable means."[69] Although the Whigs had opposed the war, they made Zachary Taylor their presidential candidate in the election of 1848, praising his military performance while muting their criticism of the war.

| style="width:The sixteen-year-old Emily Dickinson, writing to her older brother, Austin in the fall of 1847, shortly after the Battle of Chapultepec[70];vertical-align:top;color:#B2B7F2;font-size:35px;font-family:'Times New Roman',serif;font-weight:bold;text-align:left;padding:10px 10px;" | 「 | “Has the Mexican War terminated yet, and how? Are we beaten? Do you know of any nation about to besiege South Hadley [Massachusetts]? Is so, do inform me of it, for I would be glad of a chance to escape, if we are to be stormed. I suppose [our teacher] Miss [Mary] Lyon would furnish us all with daggers and order us to fight for our lives…” | style="width:The sixteen-year-old Emily Dickinson, writing to her older brother, Austin in the fall of 1847, shortly after the Battle of Chapultepec[70];vertical-align:bottom;color:#B2B7F2;font-size:36px;font-family:'Times New Roman',serif;font-weight:bold;text-align:right;padding:10px 10px;" | 」 |

Political repercussions

[編集]A month before the end of the war, Polk was criticized in a United States House of Representatives amendment to a bill praising Major General Zachary Taylor for "a war unnecessarily and unconstitutionally begun by the President of the United States." This criticism, in which Congressman Abraham Lincoln played an important role with his Spot Resolutions, followed congressional scrutiny of the war's beginnings, including factual challenges to claims made by President Polk.[71][72] The vote followed party lines, with all Whigs supporting the amendment. Lincoln's attack won luke-warm support from fellow Whigs in Illinois but was harshly counter-attacked by Democrats, who rallied pro-war sentiments in Illinois; Lincoln's Spot resolutions haunted his future campaigns in the heavily Democratic state of Illinois, and were cited by enemies well into his presidency.[73]

Effect on the U.S. Civil War

[編集]Many of the military leaders on both sides of the American Civil War had fought as junior officers in Mexico. This list includes Ulysses S. Grant, George B. McClellan, Ambrose Burnside, Stonewall Jackson, James Longstreet, George Meade, Robert E. Lee, and the future Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

President Ulysses S. Grant, who as a young army lieutenant had served in Mexico under General Taylor, recalled in his Memoirs, published in 1885, that:

Generally, the officers of the army were indifferent whether the annexation was consummated or not; but not so all of them. For myself, I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.[74]

Grant also expressed the view that the war against Mexico had brought punishment on the United States in the form of the American Civil War:

The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war. Nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times.[75]

Combatants

[編集]On the American side, the war was fought by regiments of regulars and various regiments, battalions, and companies of volunteers from the different states of the union and the Americans and some of the Mexicans in the territory of California and New Mexico. On the West Coast, the U.S. Navy fielded a battalion of sailors, in an attempt to recapture Los Angeles.[76]

United States

[編集]At the beginning of the war, the U.S. Army had eight regiments of infantry (three battalions), four artillery regiments and three mounted regiments (two dragoons, one of mounted rifles). These regiments were supplemented by 10 new regiments (nine of infantry and one of cavalry) raised for one year's service (new regiments raised for one year according to act of Congress Feb 11, 1847).[77]

State Volunteers were raised in various sized units and for various periods of time, mostly for one year. Later some were raised for the duration of the war as it became clear it was going to last longer than a year.[78]

U.S. soldiers' memoirs describe cases of looting and murder of Mexican civilians, mostly by State Volunteers. One officer's diary records:

We reached Burrita about 5 pm, many of the Louisiana volunteers were there, a lawless drunken rabble. They had driven away the inhabitants, taken possession of their houses, and were emulating each other in making beasts of themselves.[79]

John L. O'Sullivan, a vocal proponent of Manifest Destiny, later recollected:

The regulars regarded the volunteers with importance and contempt ... [The volunteers] robbed Mexicans of their cattle and corn, stole their fences for firewood, got drunk, and killed several inoffensive inhabitants of the town in the streets.

Many of the volunteers were unwanted and considered poor soldiers. The expression "Just like Gaines's army" came to refer to something useless, the phrase having originated when a group of untrained and unwilling Louisiana troops were rejected and sent back by Gen. Taylor at the beginning of the war.

The last surviving U.S. veteran of the conflict, Owen Thomas Edgar, died on September 3, 1929, at age 98.

1,563 U.S. soldiers are buried in the Mexico City National Cemetery, which is maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission.

Mexico

[編集]At the beginning of the war, Mexican forces were divided between the permanent forces (permanentes) and the active militiamen (activos). The permanent forces consisted of 12 regiments of infantry (of two battalions each), three brigades of artillery, eight regiments of cavalry, one separate squadron and a brigade of dragoons. The militia amounted to nine infantry and six cavalry regiments. In the northern territories of Mexico, presidial companies (presidiales) protected the scattered settlements there.[80]

One of the contributing factors to loss of the war by Mexico was the inferiority of their weapons. The Mexican army was using British muskets (e.g. Brown Bess) from the Napoleonic Wars. In contrast to the aging Mexican standard-issue infantry weapon, some U.S. troops had the latest U.S.-manufactured breech-loading Hall rifles and Model 1841 percussion rifles. In the later stages of the war, U.S. cavalry and officers were issued Colt Walker revolvers, of which the U.S. Army had ordered 1,000 in 1846. Throughout the war, the superiority of the U.S. artillery often carried the day.

Political divisions inside Mexico were another factor in the U.S. victory. Inside Mexico, the centralistas and republicanos vied for power, and at times these two factions inside Mexico's military fought each other rather than the invading American army. Another faction called the monarchists, whose members wanted to install a monarch (some even advocated rejoining Spain), further complicated matters. This third faction would rise to predominance in the period of the French intervention in Mexico. The ease of the American landing at Vera Cruz was in large part due to civil warfare in Mexico City, which made any real defense of the port city impossible. As Gen. Santa Anna said, "However shameful it may be to admit this, we have brought this disgraceful tragedy upon ourselves through our interminable in-fighting."

Saint Patrick's Battalion (San Patricios) was a group of several hundred immigrant soldiers, the majority Irish, who deserted the U.S. Army because of ill-treatment or sympathetic leanings to fellow Mexican Catholics. They joined the Mexican army. Most were killed in the Battle of Churubusco; about 100 were captured by the U.S. and roughly ½ were hanged as deserters. The leader, Jon Riley, was merely branded since he had deserted prior to the start of the war.

アメリカ合衆国における米墨戦争の影響

[編集]

Despite initial objections from the Whigs and abolitionists, the war would nevertheless unite the U.S. in a common cause and was fought almost entirely by volunteers. The army swelled from just over 6,000 to more than 115,000. Of these, approximately 1.5% were killed in the fighting and nearly 10% died of disease; another 12% were wounded or discharged because of disease, or both.

For years afterward, veterans continued to suffer from the debilitating diseases contracted during the campaigns. The casualty rate was thus easily over 25% for the 17 months of the war; the total casualties may have reached 35–40% if later injury- and disease-related deaths are added. [要出典] In this respect, the war was proportionately the most deadly in American military history.

During the war, political quarrels in the U.S. arose regarding the disposition of conquered Mexico. A brief "All-Mexico" movement urged annexation of the entire territory. Veterans of the war who had seen Mexico at first hand were unenthusiastic. Anti-slavery elements opposed that position and fought for the exclusion of slavery from any territory absorbed by the U.S.[81] In 1847 the House of Representatives passed the Wilmot Proviso, stipulating that none of the territory acquired should be open to slavery. The Senate avoided the issue, and a late attempt to add it to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was defeated.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was the result of Nicholas Trist's unauthorized negotiations. It was approved by the U.S. Senate on March 10, 1848, and ratified by the Mexican Congress on May 25. Mexico's cession of Alta California and Nuevo México and its recognition of U.S. sovereignty over all of Texas north of the Rio Grande formalized the addition of 1.2 million square miles (3.1 million km2) of territory to the United States. In return the U.S. agreed to pay $15 million and assumed the claims of its citizens against Mexico. A final territorial adjustment between Mexico and the U.S. was made by the Gadsden Purchase in 1853.

As late as 1880, the "Republican Campaign Textbook" by the Republican Congressional Committee[82] described the war as "Feculent, reeking Corruption" and "one of the darkest scenes in our history—a war forced upon our and the Mexican people by the high-handed usurpations of Pres't Polk in pursuit of territorial aggrandizement of the slave oligarchy."

The war was one of the most decisive events for the U.S. in the first half of the 19th century. While it marked a significant waypoint for the nation as a growing military power, it also served as a milestone especially within the U.S. narrative of Manifest Destiny. The resultant territorial gains set in motion many of the defining trends in American 19th-century history, particularly for the American West. The war did not resolve the issue of slavery in the U.S. but rather in many ways inflamed it, as potential westward expansion of the institution took an increasingly central and heated theme in national debates preceding the American Civil War. Furthermore, in doing much to extend the nation from coast to coast, the Mexican–American War was one step in the massive migrations to the West of Americans, which culminated in transcontinental railroads and the Indian wars later in the same century.

In Mexico City's Chapultepec Park, the Niños Héroes (Monument to the Heroic Cadets) commemorates the heroic sacrifice of six teenaged military cadets who fought to their deaths rather than surrender to American troops during the Battle of Chapultepec Castle on September 13, 1847. The monument is an important patriotic site in Mexico. On March 5, 1947, nearly one hundred years after the battle, U.S. President Harry S. Truman placed a wreath at the monument and stood for a moment of silence.

See also

[編集]- Battles of the Mexican–American War

- Christopher Werner, maker of the "Iron Palmetto" commemorating the loss of South Carolinians in the War

- Reconquista (Mexico)

- Republic of Texas – United States relations

General:

- History of Mexico

- List of conflicts in the United States

- List of wars involving Mexico

- Mexico-United States relations

Notes

[編集]- ^ 1846 only.

- ^ The American Army in the Mexican War: An Overview, PBS, (Mar 14, 2006) 2012年5月13日閲覧。

- ^ The U.S.-Mexican War: Some Statistics, Descendants of Mexican War Veterans, (Aug 7, 2004) 2012年5月13日閲覧。

- ^ The Organization of the Mexican Army, PBS, (Mar 14, 2006) 2012年5月13日閲覧。

- ^ See Rives, The United States and Mexico, vol. 2, p. 658

- ^ "The Annexation of Texas" U.S. Department of State. http://history.state.gov/milestones/1830-1860/TexasAnnexation, Retrieved 2012-07-06

- ^ Delay, Brian "Independent Indians and the U.S. Mexican War" The American Historical Review, Vol 112, No. l (Feb 2007), p 35

- ^ DeLay, Brian. The War of a Thousand Deserts New Haven: Yale U Press, 2008, p.286

- ^ Rives, ''The United States and Mexico'' vol. 2, pp 45–46. Books.google.com. (2007-09-28) 2011年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ Rives, pp. 48–49

- ^ http://www.jstor.org/pss/25139106 Proposals for the colonization of California by England, California Historical Society Quarterly, 1939

- ^ a b See "Republic of Texas"

- ^ a b Rives, vol. 2, pp. 165–168

- ^ Rives, vol. 2, pp. 172–173

- ^ Smith (1919) p. xi.

- ^ a b Jay (1853) p. 117.

- ^ Jay (1853) p. 119.

- ^ Donald Fithian Stevens, Origins of Instability in Early Republican Mexico (1991) p. 11.

- ^ Miguel E. Soto, "The Monarchist Conspiracy and the Mexican War" in Essays on the Mexican War ed by Wayne Cutler; Texas A&M University Press. 1986. pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Brooks (1849) pp. 61–62.

- ^ Mexican War from Global Security.com.

- ^ David Montejano (1987). Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986. University of Texas Press. p. 30

- ^ Justin Harvey Smith (1919). The war with Mexico vol. 1. Macmillan. p. 464

- ^ K. Jack Bauer (1993). Zachary Taylor: Soldier, Planter, Statesman of the Old Southwest. Louisiana State University Press. p. 149

- ^ Smith (1919) p. 279.

- ^ Faragher, John Mack, et al., eds. Out Of Many: A History of the American People. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, 2006.

- ^ “Message of President Polk, May 11, 1846”. 2008年7月20日閲覧。 “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil. She has proclaimed that hostilities have commenced, and that the two nations are now at war.”

- ^ a b Bauer (1992) p. 68.

- ^ see A. Brook Caruso: The Mexican Spy Company. 1991, p. 62-79

- ^ Jay (1853) pp. 165–166.

- ^ Jay (1853) p. 165.

- ^ See O'Sullivan's 1845 article, "Annexation," [1] United States Magazine and Democratic Review

- ^ Giddings,Joshua Reed, Speeches in Congress [1841–1852], J.P. Jewett and Company, 1853, p.17

- ^ Beveridge 1:417.

- ^ Speech of the Hon. John Quincy Adams, in the House of Representatives, on the state of the nation: delivered May 25, 1836, Internet Archive 2012年5月13日閲覧。

- ^ “James K. Polk: Third Annual Message—December 7, 1847”. Presidency.ucsb.edu. 2011年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Brooks (1849) p. 122.

- ^ Brooks (1849) pp. 91, 117.

- ^ Brooks (1849) p. 121.

- ^ Brooks (1849) p. 257.

- ^ Bauer (1992) pp. 190–191.

- ^ Silversteen, p42

- ^ Bauer (1992) p. 201.

- ^ Rives, George Lockhart, The United States and Mexico, 1821–1848: a history of the relations between the two countries from the independence of Mexico to the close of the war with the United States, Volume 2, C. Scribner's Sons, New York, 1913, p.233. Books.google.com. (2007-09-28) 2011年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Urban Warfare”. Battle of Monterrey.com. 2011年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ Dishman, Christopher (2010). A Perfect Gibraltar: The Battle for Monterrey, Mexico. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-4140-9

- ^ Roger D. Launius (1997). Alexander William Doniphan: portrait of a Missouri moderate. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1132-3

- ^ Hamalainen, Pekka. The Comanche Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 232

- ^ Meed, Douglas (2003). The Mexican War, 1846–1848. Routledge. p. 67

- ^ McAllister, Brian. “see Coffman, ''Old Army'' (1988) p. 193”. Amazon.com. 2011年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b Foos, Paul (2002). A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair. pp. 25, 103–7

- ^ Eisenhower, John S. D. (1989). So Far from God: The U.S. War With Mexico, 1846–1848. New York: Random House. p. 295. ISBN 0-8061-3279-5

- ^ Executive Document, No. 60, House of Representatives, first Session of the thirtieth Congress, pp. 1028, 1032

- ^ Carney, Stephen A. (2005), U.S. Army Campaigns of the Mexican War: The Occupation of Mexico, May 1846-July 1848 (CMH Pub 73-3), Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 30–38

- ^ Smith (1919) p. 241.

- ^ Mills, Bronwyn. U.S.-Mexican War. p. 23. ISBN 0-8160-4932-7

- ^ Davis, Kenneth C. (1995). Don’t Know Much About History. New York: Avon Books. p. 143

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2003). A People’s History of the United States. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 169

- ^ Rives, George Lockhart (1913). The United States and Mexico, 1821–1848. C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 634–636

- ^ Frazier, Donald S.. “Boundary Disputes”. US-Mexican War, 1846-1848. PBS. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ a b “Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement Between the United States of America and the United Mexican States Concluded at Guadalupe Hidalgoa”. Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. University of Dayton (academic.udayton.edu). 2007年10月25日閲覧。

- ^ “Article IX”. Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo; February 2, 1848. Lillian Goldman Law Library. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Hamalainen, 293-341

- ^ DeLay, Brian (2008). War of a thousand deserts: Indian raids and the U.S.-Mexican War. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 302

- ^ “Gadsden Purchase Treaty : December 30, 1853”. Lillian Goldman Law Library. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo”. www.ourdocuments.gov. 2007年6月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Table 16. Population: 1790 to 1990” (PDF), Population and Housing Unit Counts. 1990 Census of Population and Housing. CPH-2-1. (U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census): pp. 26–27, ISBN 99946-41-25-5

- ^ Franzius, Andrea. “California Gold -- Migrating to California: Overland, around the Horn and via Panama”. 2012年7月6日閲覧。

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1860). The Conduct of Life. p. 110. ISBN 1-4191-5736-1

- ^ Linscott, 1959, p. 218-219

- ^ “Congressional Globe, 30th Session (1848) pp. 93–95”. Memory.loc.gov. 2011年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ “House Journal, 30th Session (1848) pp. 183–184/”. Memory.loc.gov. 2011年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ Donald, David Herbert (1995). Lincoln. pp. 124, 128, 133

- ^ “Ulysses S Grant Quotes on the Military Academy and the Mexican War”. Fadedgiant.net. 2011年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Personal Memoirs of General U. S. Grant — Complete by Ulysses S. Grant”. Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “William Hugh Robarts, "Mexican War veterans : a complete roster of the regular and volunteer troops in the war between the United States and Mexico, from 1846 to 1848 ; the volunteers are arranged by states, alphabetically", BRENTANO'S (A. S. WITHERBEE & CO, Proprietors); WASHINGTON, D. C., 1887”. Archive.org (2001年3月10日). 2011年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ Robarts, "Mexican War veterans" pp.1–24

- ^ Robarts, "Mexican War veterans" pp.39–79

- ^ Bronwyn Mills U.S.-Mexican war ISBN 0-8160-4932-7.

- ^ René Chartrand, ''Santa Anna's Mexican Army 1821–48'', Illustrated by Bill Younghusband, Osprey Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1-84176-667-4, ISBN 978-1-84176-667-6. Books.google.com 2011年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ John Douglas Pitts Fuller, ''The Movement for the Acquisition of All Mexico, 1846–1848'' (1936). Books.google.com. (2008-06-12) 2011年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ Mexican–American War description from the Republican Campaign Textbook.

Bibliography

[編集]Reference works

[編集]- Crawford, Mark; Jeanne T. Heidler; David Stephen Heidler (eds.) (1999). Encyclopedia of the Mexican War. ISBN 1-57607-059-X

- Frazier, Donald S. ed. The U.S. and Mexico at War, (1998), 584; an encyclopedia with 600 articles by 200 scholars

Surveys

[編集]- Bauer, Karl Jack (1992). The Mexican War: 1846–1848. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6107-1

- De Voto, Bernard, Year of Decision 1846 (1942), well written popular history

- Greenberg, Amy S. A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico (2012).

- Henderson, Timothy J. A Glorious Defeat: Mexico and Its War with the United States (2008)

- Meed, Douglas. The Mexican War, 1846–1848 (2003). A short survey.

- Merry Robert W. A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, the Mexican War and the Conquest of the American Continent (2009)

- Smith, Justin Harvey. The War with Mexico, Vol 1. (2 vol 1919), full text online.

- The War with Mexico, Vol 2. (1919). full text online.

Military

[編集]- Bauer K. Jack. Zachary Taylor: Soldier, Planter, Statesman of the Old Southwest. Louisiana State University Press, 1985.

- Dishman, Christopher, A Perfect Gibraltar: The Battle for Monterrey, Mexico," University of Oklahoma Press, 2010 ISBN 0-8061-4140-9.

- Eisenhower, John. So Far From God: The U.S. War with Mexico, Random House (1989).

- Eubank, Damon R., Response of Kentucky to the Mexican War, 1846–1848. (Edwin Mellen Press, 2004), ISBN 978-0-7734-6495-7.

- Foos, Paul. A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict during the Mexican-War (2002).

- Fowler, Will. Santa Anna of Mexico (2007) 527pp; a major scholarly study

- Frazier, Donald S. The U.S. and Mexico at War, Macmillan (1998).

- Hamilton, Holman, Zachary Taylor: Soldier of the Republic, (1941).

- Huston, James A. The Sinews of War: Army Logistics, 1775-1953 (1966), U.S. Army; 755pp online pp 125-58

- Lewis, Lloyd. Captain Sam Grant (1950).

- Johnson, Timothy D. Winfield Scott: The Quest for Military Glory (1998)

- McCaffrey, James M. Army of Manifest Destiny: The American Soldier in the Mexican War, 1846–1848 (1994)excerpt and text search

- Smith, Justin H. "American Rule in Mexico," The American Historical Review Vol. 23, No. 2 (Jan., 1918), pp. 287–302 in JSTOR

- Smith, Justin Harvey. The War with Mexico. 2 vol (1919). Pulitzer Prize winner. full text online.

- Winders, Richard Price. Mr. Polk’s Army: The American Military Experience in the Mexican War (1997)

Political and diplomatic

[編集]- Beveridge; Albert J. Abraham Lincoln, 1809–1858. Volume: 1. 1928.

- Brack, Gene M. Mexico Views Manifest Destiny, 1821–1846: An Essay on the Origins of the Mexican War (1975).

- Fowler, Will. Tornel and Santa Anna: The Writer and the Caudillo, Mexico, 1795–1853 (2000).

- Fowler, Will. Santa Anna of Mexico (2007) 527pp; the major scholarly study excerpt and text search

- Gleijeses, Piero. "A Brush with Mexico" Diplomatic History 2005 29(2): 223–254. Issn: 0145-2096 debates in Washington before war.

- Graebner, Norman A. Empire on the Pacific: A Study in American Continental Expansion. (1955).

- Graebner, Norman A. "Lessons of the Mexican War." Pacific Historical Review 47 (1978): 325–42. in JSTOR.

- Graebner, Norman A. "The Mexican War: A Study in Causation." Pacific Historical Review 49 (1980): 405–26. in JSTOR.

- Henderson, Timothy J. A Glorious Defeat: Mexico and Its War with the United States (2007), survey

- Krauze, Enrique. Mexico: Biography of Power, (1997), textbook.

- Linscott, Robert N., Editor. 1959. Selected Poems and Letters of Emily Dickinson. Anchor Books, New York. ISBN 0-385-09423-X

- Mayers, David; Fernández Bravo, Sergio A., "La Guerra Con Mexico Y Los Disidentes Estadunidenses, 1846–1848" [The War with Mexico and US Dissenters, 1846–48]. Secuencia [Mexico] 2004 (59): 32–70. Issn: 0186-0348.

- Pinheiro, John C. Manifest Ambition: James K. Polk and Civil-Military Relations during the Mexican War (2007).

- Pletcher David M. The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War. University of Missouri Press, 1973.

- Price, Glenn W. Origins of the War with Mexico: The Polk-Stockton Intrigue. University of Texas Press, 1967.

- Reeves, Jesse S. "The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo," American Historical Review, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Jan., 1905), pp. 309–324 in JSTOR.

- Rives, George Lockhart. The United States and Mexico, 1821–1848: a history of the relations between the two countries from the independence of Mexico to the close of the war with the United States (1913) full text online

- Rodríguez Díaz, María Del Rosario. "Mexico's Vision of Manifest Destiny During the 1847 War" Journal of Popular Culture 2001 35(2): 41–50. Issn: 0022-3840.

- Ruiz, Ramon Eduardo. Triumph and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People, Norton 1992, textbook

- Schroeder John H. Mr. Polk's War: American Opposition and Dissent, 1846–1848. University of Wisconsin Press, 1973.

- Sellers Charles G. James K. Polk: Continentalist, 1843–1846 (1966), the standard biography vol 1 and 2 are online at ACLS e-books

- Smith, Justin Harvey. The War with Mexico. 2 vol (1919). Pulitzer Prize winner. full text online.

- Stephenson, Nathaniel Wright. Texas and the Mexican War: A Chronicle of Winning the Southwest. Yale University Press (1921).

- Weinberg Albert K. Manifest Destiny: A Study of Nationalist Expansionism in American History Johns Hopkins University Press, 1935.

- Yanez, Agustin. Santa Anna: Espectro de una sociedad (1996).

Memory and historiography

[編集]- Faulk, Odie B., and Stout, Joseph A., Jr., eds. The Mexican War: Changing Interpretations (1974)

- Rodriguez, Jaime Javier. The Literatures of the U.S.-Mexican War: Narrative, Time, and Identity (University of Texas Press; 2010) 306 pages. Covers works by Anglo, Mexican, and Mexican-American writers.

- Benjamin, Thomas. "Recent Historiography of the Origins of the Mexican War," New Mexico Historical Review, Summer 1979, Vol. 54 Issue 3, pp 169–181

- Vázquez, Josefina Zoraida. "La Historiografia Sobre la Guerra entre Mexico y los Estados Unidos," ["The historiography of the war between Mexico and the United States"] Histórica (02528894), 1999, Vol. 23 Issue 2, pp 475–485

Primary sources

[編集]- Calhoun, John C. The Papers of John C. Calhoun. Vol. 23: 1846, ed. by Clyde N. Wilson and Shirley Bright Cook. (1996). 598 pp

- Calhoun, John C. The Papers of John C. Calhoun. Vol. 24: December 7, 1846 – December 5, 1847 ed. by Clyde N. Wilson and Shirley Bright Cook, (1998). 727 pp.

- Conway, Christopher, ed. The U.S.-Mexican War: A Binational Reader (2010)

- Grant, Ulysses S. (1885). Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. New York: Charles L. Webster & Co

- Kendall, George Wilkins (1999). Lawrence Dilbert Cress. ed. Dispatches from the Mexican War. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press

- Polk, James, K. (1910). Milo Milton Quaife. ed. The Diary of James K. Polk: During his Presidency, 1845–1849. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co

- Robinson, Cecil, The View From Chapultepec: Mexican Writers on the Mexican War, University of Arizona Press (Tucson, 1989).

- Smith, Franklin (1991). Joseph E. Chance. ed. The Mexican War Journal of Captain Franklin Smith. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi

- George Winston and Charles Judah, ed (1968). Chronicles of the Gringos: The U.S. Army in the Mexican War, 1846–1848, Accounts of Eyewitnesses and Combatants. Albuquerque, New Mexico: The University of New Mexico Press

- Webster, Daniel (1984). Charles M. Wiltse. ed. The Papers of Daniel Webster, Correspondence. 6. Hanover, New Hampshire: The University Press of New England

- “Treaty of Guadalope Hidalgo”. Internet Sourcebook Project. 2008年11月26日閲覧。

- “28th Congress, 2nd session”. United States House Journal. 2008年11月26日閲覧。

- “29th Congress, 1st session”. United States House Journal. 2008年11月26日閲覧。

- “28th Congress, 2nd session”. United States Senate Journal. 2008年11月26日閲覧。

- “29th Congress, 1st session”. United States Senate Journal. 2008年11月26日閲覧。

- William Hugh Robarts, "Mexican War veterans: a complete roster of the regular and volunteer troops in the war between the United States and Mexico, from 1846 to 1848; the volunteers are arranged by states, alphabetically", BRENTANO'S (A. S. WITHERBEE & CO, Proprietors); WASHINGTON, D. C., 1887.

External links

[編集]Guides, bibliographies and collections

[編集]- Library of Congress Guide to the Mexican War

- The Handbook of Texas Online: Mexican War

- Reading List compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History

- Mexican War Resources

- The Mexican–American War, Illinois Historical Digitization Projects at Northern Illinois University Libraries

Media and primary sources

[編集]- Robert E. Lee Mexican War Maps in the VMI Archives

- The Mexican War and the Media, 1845–1848

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and related resources at the U.S. Library of Congress

- Letters of Winfield Scott including official reports from the front sent to the Secretary of War

- Franklin Pierce's Journal on the March from Vera Cruz

- Mexican–American War Time line

- Animated History of the Mexican–American War

Other

[編集]- PBS site of US-Mexican war program

- Battle of Monterrey Web Site – Complete Info on the battle

- A Continent Divided: The U.S. - Mexico War

- Manifest Destiny and the U.S.-Mexican War: Then and Now

- The Mexican War

- Smithsonian teaching aids for "Establishing Borders: The Expansion of the United States, 1846–48"

- A History by the Descendants of Mexican War Veterans

- Mexican–American War

- Invisible Men: Blacks and the U.S. Army in the Mexican War by Robert E. May