利用者:ハッピーハロウイン/sandbox

|

ここはハッピーハロウインさんの利用者サンドボックスです。編集を試したり下書きを置いておいたりするための場所であり、百科事典の記事ではありません。ただし、公開の場ですので、許諾されていない文章の転載はご遠慮ください。

登録利用者は自分用の利用者サンドボックスを作成できます(サンドボックスを作成する、解説)。 その他のサンドボックス: 共用サンドボックス | モジュールサンドボックス 記事がある程度できあがったら、編集方針を確認して、新規ページを作成しましょう。 |

- 利用者:ハッピーハロウイン/sandbox 交差性

- 利用者:ハッピーハロウイン/sandbox1 スタンドポイント理論

- 利用者:ハッピーハロウイン/sandbox2 相互主観性

- 利用者:ハッピーハロウイン/Standpoint feminism スタンドポイント・フェミニズム

—

交差性 en:Intersectionality 04:54, 19 June 2020 Atvica より翻訳中途。 社会階級

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

| Specific forms |

| Part of a series on |

| en:Discrimination |

|---|

| Specific forms |

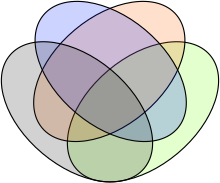

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework for understanding how aspects of a person's social and political identities (e.g., gender, race, class, sexuality, ability etc.) might combine to create unique modes of en:discrimination. Intersectionality identifies injustices that are felt by people due to a combination of factors. For example, a black woman might face discrimination from a business that is not distinctly due to her race (because the business does not discriminate against black men) nor distinctly due to her en:gender (because the business does not discriminate against white women), but due to a unique combination of the two factors.

交差性 (集合論の用語では、交叉性とも表記される, Intersectionality, インターセクショナリティ)は、個人の社会的および政治的アイデンティティ (例えば、ジェンダー、人種、階級、性別、障害など)のアスペクツ (諸局面)がどのように結合して独特の差別様式を形成するかを理解するための理論的枠組みである。交差性は、複数の要因の組み合わせによって人々が感じる不公平を識別する。例えば、黒人女性は、(黒人男性を差別していないことによる)自分の人種や、(白人女性を差別していないことによる)ジェンダーによってではなく、2つの要因が独特に組み合わさっていることによって、仕事上で差別を受けるかもしれない。

Intersectionality broadens the lens of the first en:waves of feminism, which largely focused on the experiences of women who were both white and middle-class, to include the different experiences of en:women of color, women who are poor, immigrant women, and other groups. Intersectional feminism aims to separate itself from en:white feminism by acknowledging women's different experiences and identities.[1]

交差性は、主に白人と中流階級の両方の女性の経験に焦点を当てた第一波フェミニズムの視野を拡張し、有色人種の女性、貧困と女性 (英語版)、移民女性 (英語版)、その他のグループの異なる経験を含む。交差フェミニズムは、女性のさまざまな経験やアイデンティティを認めることによって、白人フェミニズム (英語版)からの分離を目指している。[1]

Intersectionality is a qualitative en:analytic framework developed in the late 20th century that identifies how interlocking systems of power affect those who are most marginalized in society[2] and takes these relationships into account when working to promote social and political equity.[1] Intersectionality opposes analytical systems that treat each oppressive factor in isolation, as if the discrimination against black women could be explained away as only a simple sum of the discrimination against black men and the discrimination against white women.[3] Intersectionality engages in similar themes as en:triple oppression, which is the oppression associated with being a poor woman of color.

「交差性」とは、20世紀後半に開発された定性的分析の枠組みであり、社会の中で最も周縁化 [4]されている人々に、権力の結合システムがどのように影響するかを明らかにし、社会的・政治的公平性[1]を推進する際にこれらの関係を考慮する。交差性は、あたかも黒人女性に対する差別が黒人男性に対する差別と白人女性に対する差別の単純な和として説明できるかのように、それぞれの抑圧要因を個別に扱う分析システムに反対する。[5] 交差性は、三重苦 (英語版)と同様のテーマに関与しており、三重苦は、有色の貧困女性に伴う抑圧である。

Intersectionality has been critiqued as being inherently ambiguous. The ambiguity of this theory means that it can be perceived as unorganized and lacking a clear set of defining goals; this arguably means that intersectionality will be unlikely to achieve equality due to its unfocused agenda. Without a clear focus, it is difficult for a movement to create change because having such a broad theory makes it harder for people to fully understand its goals. As it is based in en:standpoint theory, critics say the focus on subjective experiences can lead to contradictions and the inability to identify common causes of oppression.

交差性は本来的に曖昧であると批判されてきた。この理論の曖昧さは、それが未組織で明確な目標設定を欠いていると知覚されることを意味する;これはおそらく、その焦点が絞られていないアジェンダのために、交差性が平等を達成する可能性が低いことを意味する。明確な焦点がなければ、そのような広い理論を持つことは人々がその目標を完全に理解することを難しくするので、変化を生み出す運動は難しい。観点や立脚点に関するスタンドポイント理論 (英語版)に基づいているため、主観的な体験に焦点を当てることは矛盾を生み、抑圧の一般的な原因を特定できなくなる可能性があると批評家は述べている。

歴史的背景

[編集]| 映像外部リンク | |

|---|---|

| Women of the World Festival 2016 | |

|

|

The term was coined by en:black feminist scholar en:Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989.[7][8][9] While the theory began as an exploration of the oppression of women of color within society, today the analysis has expanded to include many more aspects of social identity. Identities most commonly referenced in the fourth wave of feminism include race, gender, sex, sexuality, class, ability, nationality, citizenship, religion and body type. Despite being coined in 1989, the term Intersectionality was not adopted widely by feminists until the 2000s and has only grown since that time.

この用語は1989年にブラック・フェミニスト (black feminist)の学者 Kimberlé Williams Crenshawによって作り出された。[7][8][9] この理論は、社会における有色人種女性の抑圧を探求するものとして始まったが、今日では分析は社会的アイデンティティの多くの側面を含むまでに拡大している。第四波フェミニズム (Fourth-wave feminism)で最も一般的に言及されるアイデンティティには、人種、性別、性別、性別、階級、能力、国籍、市民権、宗教、体型が含まれる。1989年に造語されたにもかかわらず、 「交差性」 という用語は、 2000年代までフェミニストによって広く採用されておらず、それ以来、成長しているにすぎない。

As articulated by author en:bell hooks, the emergence of intersectionality "challenged the notion that 'gender' was the primary factor determining a woman's fate".[10] The historical exclusion of black women from the feminist movement in the United States resulted in many black 19th and 20th century feminists, such as Anna Julia Cooper, challenging their historical exclusion. This disputed the ideas of earlier feminist movements, which were primarily led by white middle-class women, suggesting that women were a homogeneous category who shared the same life experiences.[11] However, once established that the forms of oppression experienced by white middle-class women were different from those experienced by black, poor, or disabled women, feminists began seeking ways to understand how gender, race, and class combine to "determine the female destiny".[10]

著者のベル・フックス (bell hooks)によって明確にされているように、交差性の出現は「ジェンダー」が女性の運命を決定する主要な要因である」という考えに異議を唱えた。[10] アメリカで黒人女性がフェミニスト運動から歴史的に排除されてきた結果、Anna Julia Cooperのような19世紀や20世紀のブラック・フェミニストの多くが歴史的排除に挑戦するようになった。これは、主に白人中流階級の女性が主導していた初期のフェミニスト運動の考えに異議を唱えており、女性は同じ人生経験を共有する同質のカテゴリーであったことを示唆している。[12] しかしながら、白人の中流階級の女性が経験する抑圧の形態は、黒人、貧困層、障害者の女性が経験する抑圧の形態とは異なることがいったん明らかになると、フェミニストたちは、ジェンダー、人種、階級がどのように組み合わさって「女性の運命を決定する」するのかを理解する方法を模索し始めた。[10]

The concept of intersectionality is intended to illuminate dynamics that have often been overlooked by feminist theory and movements.[13] Racial inequality was a factor that was largely ignored by first-wave feminism, which was primarily concerned with gaining political equality between white men and white women. Early women's rights movements often exclusively pertained to the membership, concerns, and struggles of white women.[14] Second-wave feminism stemmed from Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and worked to dismantle sexism relating to the perceived domestic purpose of women. While feminists during this time achieved success through the Equal Pay Act of 1963, Title IX, and Roe v. Wade, they largely alienated black women from platforms in the mainstream movement.[15] However, third-wave feminism—which emerged shortly after the term "intersectionality" was coined in the late 1980s—noted the lack of attention to race, class, sexual orientation, and gender identity in early feminist movements, and tried to provide a channel to address political and social disparities.[16] Intersectionality recognizes these issues which were ignored by early social justice movements. Many recent academics, such as Leslie McCall, have argued that the introduction of the intersectionality theory was vital to sociology and that before the development of the theory, there was little research that specifically addressed the experiences of people who are subjected to multiple forms of oppression within society.[17] An example of this idea was championed by Iris Marion Young, arguing that differences must be acknowledged in order to find unifying social justice issues that create coalitions that aid in changing society for the better.[18] More specifically, this relates to the ideals of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW).[19]

交差性の概念は、フェミニストの理論や運動によってしばしば見過ごされてきた力学を明らかにすることを目的としている。[20] 人種的不平等は、第一波フェミニズムによってほとんど無視された要因であった。第一波フェミニズムは、主として白人男性と白人女性の間の政治的平等を獲得することに関心を持っていた。初期の女性の権利運動は、多くの場合、白人女性のメンバーシップ、懸念、闘争にのみ関連していた。[11] 第二波フェミニズムは、ベティ・フリーダンの 「フェミニン・ミスティーク」 に端を発し、女性の家庭的な目的に関連する性差別を解体するために活動した。この時期のフェミニストたちは、1963年の同一賃金法、Title IX、Roe v.Wadeによって成功を収めていたが、主流運動の場から黒人女性を遠ざけていた。[12] しかし、1980年代後半に「交差性」という言葉が生まれてすぐに現れた第三の波フェミニズムは、初期のフェミニスト運動において人種、階級、性的指向、ジェンダー・アイデンティティに対する注意が欠如していたことに注目し、政治的・社会的格差に取り組むためのチャンネルを提供しようとした。[13] 交差性は、初期の社会正義運動によって無視されたこれらの問題を認識している。Leslie McCallをはじめとする最近の多くの学者は、社会学にとって交差性理論の導入は不可欠であり、理論が展開される以前は、社会の中でさまざまな形態の抑圧を受けている人々の経験を具体的に扱った研究はほとんどなかったと主張している。[14] この考えの一例はアイリス・マリオン・ヤングによって支持され、社会をより良い方向に変えるのを助ける連合を作る社会正義の問題を統一するためには、違いを認めなければならないと主張した。[15] より具体的には、黒人女性会議 (NCNW) の理念に関するものである。[16]

The term also has historical and theoretical links to the concept of "simultaneity", which was advanced during the 1970s by members of the Combahee River Collective in Boston, Massachusetts.[21] Simultaneity is explained as the simultaneous influences of race, class, gender, and sexuality, which informed the member's lives and their resistance to oppression.[22] Thus, the women of the Combahee River Collective advanced an understanding of African-American experiences that challenged analyses emerging from Black and male-centered social movements, as well as those from mainstream cisgender, white, middle-class, heterosexual feminists.[23]

1970年代にマサチューセッツ州ボストンのCombahee River Collectiveによって提唱された「同時性」概念とも歴史的、理論的にリンクしている。[17] 同時性は、人種、階級、性別、セクシュアリティの同時的影響として説明され、それがメンバーの生活と抑圧への抵抗を知らせた。[18] このように、Combahee River Collectiveの女性たちは、黒人や男性中心の社会運動から出てきた分析や、主流のシスジェンダー、白人、中産階級、異性愛のフェミニストから出てきた分析に異議を唱えるアフリカ系アメリカ人の経験に対する理解を深めた。[19]

Since the term was coined, many feminist scholars have emerged with historical support for the intersectional theory. These women include en:Beverly Guy-Sheftall and her fellow contributors to Words of Fire: An Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought, a collection of articles describing the multiple oppressions black women in America have experienced from the 1830s to contemporary times. Guy-Sheftall speaks about the constant premises that influence the lives of African-American women, saying, "Black women experience a special kind of oppression and suffering in this country which is racist, sexist, and classist because of their dual race and gender identity and their limited access to economic resources."[24] Other writers and theorists were using intersectional analysis in their work before the term was coined. For example, Deborah K. King published the article "Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology" in 1988, just before Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality. In the article King addresses what soon became the foundation for intersectionality, saying, "Black women have long recognized the special circumstances of our lives in the United States: the commonalities that we share with all women, as well as the bonds that connect us to the men of our race."[25] Additionally, Gloria Wekker describes how Gloria Anzaldúa's work as a Chicana feminist theorist exemplifies how "existent categories for identity are strikingly not dealt with in separate or mutually exclusive terms, but are always referred to in relation to one another".[26] Wekker also points to the words and activism of Sojourner Truth as an example of an intersectional approach to social justice.[26] In her speech, "Ain’t I a Woman?", Truth identifies the difference between the oppression of white and black women. She says that white women are often treated as emotional and delicate while black women are subjected to racist abuse. However, this was largely dismissed by white feminists who worried that this would distract from their goal of women's suffrage and instead focused their attention on emancipation.[27]

この言葉が造語されて以来、多くのフェミニスト学者が歴史的に横断的理論を支持するようになった。これらの女性の中には、ビバリー・ガイ・シェフトール ([:en:Beverly Guy-Sheftall]])や、 「炎の言葉:アフリカ系アメリカ人女性思想集」 に寄稿した仲間たちも含まれている。1830年から現代にかけてアメリカの黒人女性が経験した数々の抑圧について書かれた記事を集めたものである。Guy-Sheftallは、アフリカ系アメリカ人女性の生活に影響を与える一定の前提について、「黒人女性は、二重の人種と性同一性、経済的資源へのアクセスが限られていることから、人種差別主義者、性差別主義者、および階級差別主義者であるこの国で、特別な種類の抑圧と苦痛を経験する。」と述べている [20] 。たとえば、デボラ・K・キングは、クレンショーが「複数の危険と複数の意識:黒人フェミニストイデオロギーの文脈」という用語を考え出す直前の1988年に論文を発表した。記事の中でキングは、まもなく相互分離性の基盤となったものについて触れ、「黒人女性は長い間、米国での私たちの生活の特殊な状況を認識してきました。それは、私たちがすべての女性と共有している共通点と、私たちを人種の男性と結び付ける絆です。」と述べている。 [28] さらにグロリア・ウェッカーは、グロリア・アンザルドゥのチカーナのフェミニストとしての研究が、いかに「同一性のための存在するカテゴリーは、分離または相互に排他的な用語で著しく扱われないが、常にお互いに関連して参照される」ことを実証しているかを述べている。[22] Wekkerはまた、社会正義への横断的アプローチの一例として、ソジャーナー・トゥルースの言葉と行動主義を挙げている。[26] Wekker also points to the words and activism of Sojourner Truth as an example of an intersectional approach to social justice.[26] 「私は女?」([[:en:"Ain’t I a Woman?]“)という演説の中で、真実は白人女性と黒人女性の抑圧の違いを明らかにしている。彼女によると、白人女性は感情的で繊細な扱いを受け、黒人女性は人種差別的な虐待を受けています。しかし、これが女性参政権の目的からそれるのではないかと心配し、解放に関心を向ける白人フェミニストたちによって大部分が退けられた。[29]

フェミニスト思想

[編集]| フェミニズム |

|---|

|

In 1989, en:Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term "intersectionality" in a paper as a way to help explain the oppression of African-American women. Crenshaw's term is now at the forefront of national conversations about racial justice, identity politics, and policing—and over the years has helped shape legal discussions.[7][8][9] She used the term in her crucial 1989 paper for the University of Chicago Legal Forum, "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Anti-discrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics".[30][31] In her work, Crenshaw discusses Black feminism, arguing that the experience of being a black woman cannot be understood in independent terms of either being black or a woman. Rather, it must include interactions between the two identities, which, she adds, should frequently reinforce one another.[32]

1989年、キンバーレ・クレンショーは、アフリカ系アメリカ人女性の抑圧を説明する一助となる論文の中で、「交差性」という言葉を作り出した。Crenshawの任期は現在、人種的正義、アイデンティティ政治、警察についての国内の議論の最前線にあり、長年にわたって法的議論の形成に貢献してきた。[5] [6] [7] 彼女は1989年に発表したシカゴ大学リーガルフォーラムの重要な論文「人種と性の相互関係を議論する:黒人フェミニストによる反差別主義、フェミニスト理論、反人種差別主義政治への批判」でこの用語を使用した。[24] [25] Crenshawは作品の中で黒人フェミニズムを論じ、黒人女性であるという経験は、黒人であるということと女性であるということのどちらからも独立して理解することはできないと論じている。むしろ、2つのアイデンティティ間の相互作用が含まれていなければならず、それはしばしばお互いを強化するはずだ、と彼女は付け加えた。[26]

In order to show that non-white women have a vastly different experience from white women due to their race and/or class and that their experiences are not easily voiced or amplified, Crenshaw explores two types of male violence against women: domestic violence and rape. Through her analysis of these two forms of male violence against women, Crenshaw says that the experiences of non-white women consist of a combination of both racism and sexism.[33] She says that because non-white women are present within discourses that have been designed to address either race or sex—but not both at the same time—non-white women are marginalized within both of these systems of oppression as a result.[33]

非白人女性が人種や階級のために白人女性とは全く異なる経験をしており、その経験が容易に発言したり増幅されたりしないことを示すために、Crenshawは女性に対する2つのタイプの男性の暴力を調査した:ドメスティックバイオレンスとレイプである。Crenshaw氏は、女性に対するこれら2つのタイプの男性暴力の分析を通して、非白人女性の経験は人種差別と性差別の両方の組み合わせから成ると述べている。[30] 彼女によると、人種と性のどちらかをテーマにしているが、同時に両方ではない談話の中に非白人女性が存在するため、結果的に非白人女性はこれら両方の抑圧システムの中で周縁化されているという。[30]

In her work, Crenshaw identifies three aspects of intersectionality that affect the visibility of non-white women: structural intersectionality, political intersectionality, and representational intersectionality. Structural intersectionality deals with how non-white women experience domestic violence and rape in a manner qualitatively different than that of white women. Political intersectionality examines how laws and policies intended to increase equality have paradoxically decreased the visibility of violence against non-white women. Finally, representational intersectionality delves into how pop culture portrayals of non-white women can obscure their own authentic lived experiences.[33]

Crenshawは、非白人女性の認知度に影響を与える3つの側面、すなわち構造的な相互分離性、政治的な相互分離性、および代表的な相互分離性を指摘している。構造的な相互分離性は、白人女性とは質的に異なる方法で非白人女性が家庭内暴力やレイプをどのように経験するかを扱う。政治的な分断性は、平等性を高めようとする法律や政策が、白人以外の女性に対する暴力の認知度を逆説的に低下させてきたことを検証している。最後に、代表的な相互分離性は、白人以外の女性に対するポップカルチャーの描写が、どのようにして自分自身の本当の人生経験を覆い隠すことができるかを探求する。[30]

The term gained prominence in the 1990s, particularly in the wake of the further development of Crenshaw's work in the writings of sociologist Patricia Hill Collins. Crenshaw's term, Collins says, replaced her own previous coinage "black feminist thought", and "increased the general applicability of her theory from African American women to all women".[34]:61 Much like Crenshaw, Collins argues that cultural patterns of oppression are not only interrelated, but are bound together and influenced by the intersectional systems of society, such as race, gender, class, and ethnicity.[35]:42 Collins describes this as "interlocking social institutions [that] have relied on multiple forms of segregation... to produce unjust results".[36]

Crenshawは、非白人女性の認知度に影響を与える3つの側面、すなわち構造的な相互分離性、政治的な相互分離性、および代表的な相互分離性を指摘している。構造的な相互分離性は、白人女性とは質的に異なる方法で非白人女性が家庭内暴力やレイプをどのように経験するかを扱う。政治的な分断性は、平等性を高めようとする法律や政策が、白人以外の女性に対する暴力の認知度を逆説的に低下させてきたことを検証している。最後に、代表的な相互分離性は、白人以外の女性に対するポップカルチャーの描写が、どのようにして自分自身の本当の人生経験を覆い隠すことができるかを探求する。[30]

Collins sought to create frameworks to think about intersectionality, rather than expanding on the theory itself. She identified three main branches of study within intersectionality. One branch deals with the background, ideas, issues, conflicts, and debates within intersectionality. Another branch seeks to apply intersectionality as an analytical strategy to various social institutions in order to examine how they might perpetuate social inequality. The final branch formulates intersectionality as a critical praxis to determine how social justice initiatives can use intersectionality to bring about social change.[37]

この用語は、特に社会学者パトリシア・ヒル・コリンズの著作におけるクレショーの研究がさらに発展したことを受けて、1990年代に有名になった。コリンズによると、グレンショーの任期は、彼女自身のそれまでの貨幣「黒人フェミニストの思想」と「彼女の理論のアフリカ系アメリカ人女性からすべての女性への一般的な適用性を高めた」に取って代わった。[31] :61 Crenshawと同様に、Collinsは抑圧の文化的パターンは相互に関連しているだけでなく、人種、性別、階級、民族といった社会の横断的システムと結びついており、影響を受けていると論じている。[32] :42 Collinsはこれを「複数の形態の人種差別に依存してきた社会制度が絡み合って...不当な結果を生んでいる」と表現しています。[33

The ideas behind intersectional feminism existed long before the term was coined. Sojourner Truth's 1851 "Ain't I a Woman?" speech, for example, exemplifies intersectionality, in which she spoke from her racialized position as a former slave to critique essentialist notions of femininity.[38] Similarly, in her 1892 essay, "The Colored Woman's Office", Anna Julia Cooper identifies black women as the most important actors in social change movements, because of their experience with multiple facets of oppression.[39]

コリンズは、理論自体を拡張するのではなく、相互分離性について考えるためのフレームワークを作ろうとした。彼女は交差性の範囲内で3つの主な研究分野を特定した。1つの部門は、背景、アイデア、問題、衝突、および交差性内の議論を扱う。もう1つの部門は、社会的不平等をどのように永続させるかを検討するために、さまざまな社会制度に分析戦略として交差性を適用しようとしている。最後の分科では、社会正義の取り組みが社会的変化をもたらすためにどのように相互分離性を利用できるかを判断するための重要な実践として、相互分離性を定式化する。[34] 部門間フェミニズムの背後にある思想は、この言葉が生まれるずっと前から存在していた。例えば、ソジャーナー・トゥルースの1851年「私は女ではありませんか?」のスピーチは、彼女がかつての奴隷としての人種差別的な立場から、女性らしさの本質主義的な概念を批判していたことが交差性を例証している。[35] 同様に、1892年のエッセイ「有色婦人事務所」でアンナ・ジュリア・クーパーは、抑圧の複数の側面を経験していることから、黒人女性を社会変革運動の最も重要な担い手であると見なしている。[36]q

A key writer who focused on intersectionality was Audre Lorde, who was a self-proclaimed "Black, Lesbian, Mother, Warrior, Poet".[40] Even in the title she gave herself, Lorde expressed her multifaceted personhood and demonstrated her intersectional struggles with being a black, gay woman. Lorde commented in her essay "The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house" that she was living in "a country where racism, sexism, and homophobia are inseparable".[41] Here, Lorde perfectly outlines the importance of intersectionality as she acknowledges that different prejudices are inherently linked.

相互分離性に焦点を当てた主要な作家は、自称「黒人、レズビアン、母親、戦士、詩人」のアウドレ・ロルドであった。[37] 自分自身に与えたタイトルでさえ、ローデは多面的な人格を表現し、黒人でゲイの女性であることとの組織間の葛藤を示した。ローデはエッセイ「主人の道具は、決して主人の家を解体しない」の中で、「人種差別、性差別、および同性愛嫌悪が不可分である国」に住んでいるとコメントした。[38] ここで、Lordeは、異なる偏見が本質的に関連していることを認めているので、交差性の重要性を完全に概説している。

Though intersectionality began with the exploration of the interplay between gender and race, over time other identities and oppressions were added to the theory. For example, in 1981 Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa published the first edition of This Bridge Called My Back. This anthology explored how classifications of sexual orientation and class also mix with those of race and gender to create even more distinct political categories. Many black, Latina, and Asian writers featured in the collection stress how their sexuality interacts with their race and gender to inform their perspectives. Similarly, poor women of color detail how their socio-economic status adds a layer of nuance to their identities, ignored or misunderstood by middle-class white feminists.[42]

性と人種の相互関係の探求から始まったが、時間の経過とともに他のアイデンティティや抑圧も理論に加えられた。例えば、1981年、チェリー・モラガとグロリア・アンザルドゥアは 「マイ・バックと呼ばれる橋」 の初版を出版した。このアンソロジーでは、性的指向や階級の分類が、人種や性別の分類とどのように絡み合い、より明確な政治的カテゴリーを形成しているかを探求した。黒人、ラテン系、アジア系の作家の多くは、自分の視点を伝えるために、自分の性的能力が人種や性別とどのように関係しているかを強調しています。同様に、貧しい有色人種の女性は、中産階級の白人フェミニストに無視されたり誤解されたりして、自分の社会経済的地位がどのように自分のアイデンティティにニュアンスの層を加えているのかを詳述している。[39]

According to black feminists and many white feminists, experiences of class, gender, and sexuality cannot be adequately understood unless the influence of racialization is carefully considered. This focus on racialization was highlighted many times by scholar and feminist bell hooks, specifically in her 1981 book Ain't I A Woman: Black Women and Feminism.[43] Feminists argue that an understanding of intersectionality is a vital element of gaining political and social equality and improving our democratic system.[44] Collins's theory represents the sociological crossroads between modern and post-modern feminist thought.[35]

黒人フェミニストや多くの白人フェミニストによれば、人種差別の影響を慎重に考慮しなければ、階級、性別、セクシュアリティの経験を十分に理解することはできない。この人種差別化への焦点は、特に彼女の1981年の著書 「Ain't I A Woman:Black Women and Feminism」 の中で、学者やフェミニストのベルフックによって何度も強調された。[40] フェミニストたちは、政治的・社会的平等を獲得し、民主主義体制を改善するためには、交差性を理解することが不可欠であると主張している。[41] コリンズの理論は、近代とポストモダンのフェミニスト思想の間の社会学的岐路を象徴している。[32]

Marie-Claire Belleau argues for "strategic intersectionality" in order to foster cooperation between feminisms of different ethnicities.[45]:51 She refers to different nat-cult (national-cultural) groups that produce unique types of feminisms. Using Québécois nat-cult as an example, Belleau says that many nat-cult groups contain infinite sub-identities within themselves, arguing that there are endless ways in which different feminisms can cooperate by using strategic intersectionality, and that these partnerships can help bridge gaps between "dominant and marginal" groups.[45]:54 Belleau argues that, through strategic intersectionality, differences between nat-cult feminisms are neither essentialist nor universal, but should be understood as resulting from socio-cultural contexts. Furthermore, the performances of these nat-cult feminisms are also not essentialist. Instead, they are strategies.[45]

マリー・クレール・ベローは、異なる民族のフェミニズム間の協力を促進するために、「戦略的相互関係」を主張する。[42] :51彼女は、独特なタイプのフェミニズムを生み出すさまざまな自然崇拝 (国家文化) グループに言及している。ベローは、自然崇拝のケベコワを例に挙げて、多くの自然崇拝グループは、その中に無限のサブ・アイデンティティを持っていると言い、異なるフェミニズムが戦略的な交差性を利用して協力できる無限の方法があり、これらのパートナーシップは、「優勢で限界の」グループ間のギャップを埋めるのに役立つと主張する。[42] :54ベローは、戦略的な相互関係を通じて、自然崇拝の女性主義の違いは本質主義でも普遍的でもないが、社会文化的文脈から生じるものとして理解されるべきだと主張する。さらに、これらの自然崇拝的なフェミニズムのパフォーマンスも本質主義ではない。代わりに、それらは戦略です。[42]

Similarly, Intersectional theorists like Vrushali Patil argue that intersectionality ought to recognize transborder constructions of racial and cultural hierarchies. About the effect of the state on identity formation, Patil says: "If we continue to neglect cross-border dynamics and fail to problematize the nation and its emergence via transnational processes, our analyses will remain tethered to the spatialities and temporalities of colonial modernity."[46]

同様に、Vrushali Patilのような部門間理論家は、交差性は人種的、文化的階層の国境を越えた構築を認めるべきだと主張する。アイデンティティ形成に対する国家の影響について、Patilは「もし私たちが国境を越えた力学を無視し続け、国境を越えたプロセスを通じて国家とその出現を問題にしなければ、私たちの分析は植民地時代の空間と時間に縛られたままになるだろう。」と言う。 [43]

マルクス主義フェミニスト批判論

[編集]Template:Marxism W. E. B. Du Bois theorized that the intersectional paradigms of race, class, and nation might explain certain aspects of the black political economy. Collins writes: "Du Bois saw race, class, and nation not primarily as personal identity categories but as social hierarchies that shaped African-American access to status, poverty, and power."[35]:44 Du Bois omitted gender from his theory and considered it more of a personal identity category.

W.E.B.デュ・ボワは、人種、階級、国家の横断的パラダイムが、黒人政治経済のある側面を説明するかもしれないと理論化した。Collinsは以下のように書いている:「デュボアは、人種、階級、国家を、主として個人のアイデンティティ・カテゴリーとしてではなく、アフリカ系アメリカ人の地位、貧困、権力へのアクセスを形作る社会階層として見ていた。」 [32] :44 Du Boisは彼の理論からジェンダーを除外し、それをより個人的アイデンティティの範疇であると考えた。

Cheryl Townsend Gilkes expands on this by pointing out the value of centering on the experiences of black women. Joy James takes things one step further by "using paradigms of intersectionality in interpreting social phenomena". Collins later integrated these three views by examining a black political economy through the centering of black women's experiences and the use of a theoretical framework of intersectionality.[35]:44

Cheryl Townsend Gilkes氏は、黒人女性の経験を中心とすることの価値を指摘することで、これをさらに拡大している。Joy Jamesはさらに一歩進んで、「社会現象を解釈する際に交差性のパラダイムを用いること」と言っています。後にコリンズは、黒人女性の経験を中心とした黒人の政治経済を考察し、相互関係の理論的枠組みを用いて、これら3つの見解を統合した。[32] :44

Collins uses a Marxist feminist approach and applies her intersectional principles to what she calls the "work/family nexus and black women's poverty". In her 2000 article "Black Political Economy" she describes how, in her view, the intersections of consumer racism, gender hierarchies, and disadvantages in the labor market can be centered on black women's unique experiences. Considering this from a historical perspective and examining interracial marriage laws and property inheritance laws creates what Collins terms a "distinctive work/family nexus that in turn influences the overall patterns of black political economy".[35]:45–46 For example, anti-miscegenation laws effectively suppressed the upward economic mobility of black women.

コリンズは、マルクス主義フェミニストのアプローチを用い、彼女が「仕事と家族のつながりと黒人女性の貧困」と呼ぶものに、彼女の部門間の原理を適用している。2000年の記事「ブラック・ポリティカル・エコノミー」の中で、彼女は、消費者の人種差別、性の上下関係、そして労働市場での不利な条件が交差する部分が、黒人女性特有の体験にどのように集中し得るかについて述べている。これを歴史的観点から考察し、異人種間結婚法や財産相続法を検討することで、コリンズが「黒人の政治経済の全体的なパターンに影響する特有の仕事/家族のつながり」と呼ぶものが生まれる。[32] :45–46例えば、女性に対する性差別禁止法は、黒人女性の上向きの経済的移動を効果的に抑制した。

The intersectionality of race and gender has been shown to have a visible impact on the labor market. "Sociological research clearly shows that accounting for education, experience, and skill does not fully explain significant differences in labor market outcomes."[47]:506 The three main domains in which we see the impact of intersectionality are wages, discrimination, and domestic labor. Those who experience privilege within the social hierarchy in terms of race, gender and socio-economic status are less likely to receive lower wages, to be subjected to stereotypes and discriminated against, or to be hired for exploitative domestic positions. Studies of the labor market and intersectionality provide a better understanding of economic inequalities and the implications of the multidimensional impact of race and gender on social status within society.[47]:506–507

人種と性別の相互関係は、労働市場に明らかな影響を及ぼすことが示されている。「社会学的研究によれば、教育、経験、技能を考慮しても、労働市場の成果の有意差を十分に説明することはできない。」 [44] :506交差性の影響が見られる3つの主な領域は賃金、差別、家事労働である。人種、性別、社会経済的地位の面で社会階層内で特権を経験している人々は、低賃金を受け取ったり、ステレオタイプにさらされ、差別されたり、搾取的な家庭内の地位のために雇用される可能性が低い。労働市場と交差性の研究は、経済的不平等と、社会における社会的地位に対する人種とジェンダーの多面的な影響の意味についてのより良い理解を提供する。[44] :506–507

キーコンセプト

[編集]Interlocking matrix of oppression

[編集]Collins refers to the various intersections of social inequality as the matrix of domination. These are also known as "vectors of oppression and privilege".[48]:204 These terms refer to how differences among people (sexual orientation, class, race, age, etc.) serve as oppressive measures towards women and change the experience of living as a woman in society. Collins, Audre Lorde (in Sister Outsider), and bell hooks point towards either/or thinking as an influence on this oppression and as further intensifying these differences.[49] Specifically, Collins refers to this as the construct of dichotomous oppositional difference. This construct is characterized by its focus on differences rather than similarities.[50]:S20 Lisa A. Flores suggests, when individuals live in the borders, they "find themselves with a foot in both worlds". The result is "the sense of being neither" exclusively one identity nor another.[51]

圧縮のインターロックマトリックス コリンズは、社会的不平等のさまざまな交差を支配のマトリックスと呼んでいる。これらは「抑圧と特権のベクトル」とも呼ばれます。[45] :204これらの用語は、人々の間の違い(性的指向、階級、人種、年齢など。)がどのように女性に対する抑圧的な手段となり、社会における女性としての生活の経験を変化させるかについて言及している。コリンズ、オードル・ローデ(シスター・アウトサイダーで)、ベル・フックは、この抑圧に影響を与え、この差をさらに強めるものとして、あるいはそのいずれかを指摘している。[46] 特に、Collinsはこれを二値的な反抗的差異の構造と呼んでいる。この構成体は類似性よりも相違に焦点を当てることが特徴である。[47] :S 20 Lisa A.Floresは、国境で生活する個人は「両方の世界に足を踏み入れることになる」と示唆している。その結果、1つのアイデンティティでも別のアイデンティティでも「どちらでもないという感覚」することになる。[48]

Standpoint epistemology and the outsider within

[編集]Both Collins and Dorothy Smith have been instrumental in providing a sociological definition of standpoint theory. A standpoint is an individual's unique world perspective. The theoretical basis of this approach views societal knowledge as being located within an individual's specific geographic location. In turn, knowledge becomes distinctly unique and subjective; it varies depending on the social conditions under which it was produced.[52]:392

立場認識論と内部の部外者 コリンズとドロシー・スミスはともに、立場理論の社会学的定義を提供してきた。立場とは個人の世界観である。このアプローチの理論的基礎は、社会的知識が個人の特定の地理的位置内に位置しているとみなすことである。その結果、知識は明らかに独特で主観的なものになる。それはそれが生産された社会的条件によって変わる。[49] :392

The concept of the outsider within refers to a unique standpoint encompassing the self, family, and society.[50]:S14 This relates to the specific experiences to which people are subjected as they move from a common cultural world (i.e., family) to that of modern society.[48]:207 Therefore, even though a woman—especially a Black woman—may become influential in a particular field, she may feel as though she does not belong. Their personalities, behavior, and cultural being overshadow their value as an individual; thus, they become the outsider within.[50]:S14

アウトサイダーの概念は、自己、家族、社会を包含する独自の視点を意味する。[47] :S 14これは、人々が共通の文化的世界(つまり、ファミリ)から現代社会の文化的世界に移動する際に受ける特定の経験に関するものである。[45] :207そのため、女性、特に黒人女性が特定の分野で影響力を持つようになっても、まるで自分が属していないかのように感じることがあります。彼らの性格、行動、文化的な存在は、個人としての価値を覆い隠している。つまり、彼らは内なる部外者になるのです。[47] :S 14

Resisting oppression

[編集]Speaking from a critical standpoint, Collins points out that Brittan and Maynard say that "domination always involves the objectification of the dominated; all forms of oppression imply the devaluation of the subjectivity of the oppressed".[50]:S18 She later notes that self-valuation and self-definition are two ways of resisting oppression. Practicing self-awareness helps to preserve the self-esteem of the group that is being oppressed and allows them to avoid any dehumanizing outside influences.

操作を元に戻す 批判的な観点から言えば、BrittanとMaynardは「支配は常に支配者の客観化を伴う;あらゆる形態の抑圧は、抑圧された人々の主観性の低下を意味する」と述べている。[47] :S 18彼女は後に、自己評価と自己定義は抑圧に抵抗する2つの方法であると述べている。自己認識を実践することで、抑圧されている集団の自尊心を保つことができ、人間性を失わせるような外部からの影響を避けることができます。

Marginalized groups often gain a status of being an "other".[50]:S18 In essence, you are "an other" if you are different from what Audre Lorde calls the mythical norm. "Others" are virtually anyone that differs from the societal schema of an average white male. Gloria Anzaldúa theorizes that the sociological term for this is "othering", or specifically attempting to establish a person as unacceptable based on a certain criterion that fails to be met.[48]:205

疎外された集団はしばしば「その他」の地位を得る。[47] :S 18本質的に、アウドレ・ロルデが神話上の規範と呼ぶものと異なるならば、あなたは「他の」である。「その他の証券」とは、平均的な白人男性の社会的図式とは異なる、事実上すべての人を指す。GloriaAnzaldúaは、これの社会学的用語は「オザリング」であり、具体的には、満たされていない特定の基準に基づいて人を受け入れられないと立証しようとしている、と理論化している。[45] :205

In practice

[編集]この記事はその主題がsectionに置かれた記述になっており、世界的観点から説明されていない可能性があります。 (2017年3月) |

Intersectionality can be applied to nearly all fields from politics,[53][54] education[17][39][55] healthcare,[56][57] and employment, to economics.[58] For example, within the institution of education, Sandra Jones' research on working-class women in academia takes into consideration meritocracy within all social strata, but argues that it is complicated by race and the external forces that oppress.[55] Additionally, people of color often experience differential treatment in the healthcare system. For example, in the period immediately after 9/11 researchers noted low birth weights and other poor birth outcomes among Muslim and Arab Americans, a result they connected to the increased racial and religious discrimination of the time.[59] Some researchers have also argued that immigration policies can affect health outcomes through mechanisms such as stress, restrictions on access to health care, and the social determinants of health.[57]

交差性は、政治、 [50] [51] 教育 [17] [36] [52] 医療、 [53] [54] そして雇用から経済に至るほとんどすべての分野に適用できる。[55] 例えば、教育機関内では、サンドラ・ジョーンズの学界の労働者階級の女性に関する研究は、あらゆる社会階層の能力主義を考慮に入れているが、人種と抑圧する外的要因によって複雑になっていると論じている。[52] さらに、有色人種は医療制度において差別的な治療を受けることが多い。例えば、9/11の直後の期間に、研究者は、イスラム教徒とアラブ系アメリカ人の間で低出生体重と他の不良な出生結果を指摘し、その結果、彼らは当時の人種的、宗教的差別の増加につながった。[56] 移民政策は、ストレス、医療へのアクセス制限、健康の社会的決定要因などのメカニズムを通じて、健康上のアウトカムに影響を及ぼし得ると主張する研究者もいる。[54]

Additionally, applications with regard to property and wealth can be traced to the American historical narrative that is filled "with tensions and struggles over property—in its various forms. From the removal of Native Americans (and later Japanese Americans) from the land, to military conquest of the Mexicans, to the construction of Africans as property, the ability to define, possess, and own property has been a central feature of power in America ... [and where] social benefits accrue largely to property owners."[58] One could apply the intersectionality framework analysis to various areas where race, class, gender, sexuality and ability are affected by policies, procedures, practices, and laws in "context-specific inquiries, including, for example, analyzing the multiple ways that race and gender interact with class in the labor market; interrogating the ways that states constitute regulatory regimes of identity, reproduction, and family formation";[60] and examining the inequities in "the power relations [of the intersectionality] of whiteness ... [where] the denial of power and privilege ... of whiteness, and middle-classness", while not addressing "the role of power it wields in social relations".[61]

さらに、財産や富に関する申請は、「さまざまな形で、財産をめぐる緊張と争いで。アメリカ先住民(その後の日系アメリカ人)の土地からの立ち退きから、メキシコ人の軍事的征服、財産としてのアフリカ人の建設まで、財産を定義し、所有し、所有する能力はアメリカにおける権力の中心的な特徴であり... [どこで]、社会的利益は主に財産所有者に生じる。」に満ちた米国の歴史的叙述に遡ることができる [55] 「例えば、人種や性別が労働市場の階級と相互作用する複数の方法の分析など、状況に応じた質問;国家が同一性、生殖、家族形成の規制制度を構成する方法に疑問を投げかけること」では、人種、階級、性別、セクシュアリティ、能力が政策、手続き、慣行、法律によって影響を受けるさまざまな分野に、相互接続性フレームワーク分析を適用することができる。[57] を参照し、「社会関係においてそれが行使する力の役割」には触れずに、「白人の力関係[相互関係の] ...権力と特権の否認...白人と中流階級の」における不等式を検証する。[58]

Intersectionality in a global context

[編集]Over the last couple of decades in the European Union (EU), there has been discussion regarding the intersections of social classifications and the need to acknowledge their functions. Before Crenshaw coined her definition of intersectionality, there was a debate on what these societal categories were, and how they played a role in the lives of many minorities. What was once a more cut and dried categorization between gender, race, and class has turned into a multidimensional intersection of "race" including religion, sexuality, ethnicities, etc. In the EU and UK, they refer to these intersections under the notion of multiple discrimination. The EU passed a non-discrimination law which addresses these multiple intersections; however, there is debate on whether the law is still proactively focusing on the proper inequalities.[62] The EU is not the only organization that is acknowledging this concept. People around the world are taking a new approach when identifying other identities as well as their own; however, there are still places that follow the traditional process of categorization as stated in the following quote. "The impact of patriarchy and traditional assumptions about gender and families are evident in the lives of Chinese migrant workers (Chow, Tong), sex workers and their clients in South Korea (Shin), and Indian widows (Chauhan), but also Ukrainian migrants (Amelina) and Australian men of the new global middle class (Connell)."[63] This text suggests that there are many more intersections of discrimination for people around the globe than Crenshaw originally accounted for in her definition.

グローバルコンテキストの交差 この20年間、欧州連合 (EU) において、社会的分類の交差とそれらの機能を認識する必要性に関する議論があった。クレンショーが相互分離性の定義を作る前に、これらの社会的カテゴリーが何であり、多くのマイノリティの生活においてどのような役割を果たしているかについて議論があった。かつては、性別、人種、階級の間の単純なカテゴリー化であったものが、宗教、性、民族などを含む「レース」の多次元的な交点へと変化した。EUや英国では、多重差別の概念の下で、これらの交点を指す。EUは、これらの複数の交差点に対処する差別禁止法を可決した。しかし、同法が依然として、適切な不平等に積極的に焦点を合わせているかどうかについては議論がある。[59] この概念を認めているのはEUだけではない。世界中の人々が、自分のアイデンティティだけでなく他のアイデンティティを識別する際に、新しいアプローチを採用しています。ただし、以下の引用のように伝統的な分類の流れを汲むものもある。「家父長制の影響とジェンダーと家族についての伝統的な仮定は、韓国の中国人移住労働者(董卓)、セックスワーカーとその客 (シン) 、インド人未亡人 (チャウハン) の生活だけでなく、ウクライナ人移住者 (アメリナ) 、そして新しい世界的中流階級のオーストラリア人男性 (コネル) の生活にも明らかである。」 [60] この文章は、世界中の人々にとっての差別の交差部分は、クレンショーの定義でもともと考慮されていたよりもずっと多いことを示唆している。

For example, Chandra Mohanty discusses alliances between women throughout the world as intersectionality in a global context. She rejects the western feminist theory, especially when it writes about global women of color and generally associated "third world women". She argues that "third world women" are often thought of as a homogenous entity, when, in fact, their experience of oppression is informed by their geography, history, and culture. When western feminists write about women in the global South in this way, they dismiss the inherent intersecting identities that are present in the dynamic of feminism in the global South. Mohanty questions the performance of intersectionality and relationality of power structures within the US and colonialism and how to work across identities with this history of colonial power structures.[64] This lack of homogeneity and intersecting identities can be seen through Feminism in India, which goes over how women in India practice feminism within social structures and the continuing effects of colonization that differ from that of Western and other non-Western countries.

例えば、Chandra Mohantyは、グローバルな文脈での相互分離性として、世界中の女性間の同盟について論じている。彼女は西洋のフェミニスト理論を、特に世界的な有色人種の女性や一般的に連想される女性「第三世界の女性」について書くときには、拒否する。彼女は、「第三世界の女性」はしばしば均質な存在と考えられているが、実際には、抑圧の経験は地理的、歴史的、文化的に知らされていると主張する。西洋のフェミニストたちがこのように世界の南の女性について書くとき、彼らは世界の南のフェミニズムの力学に内在する交差するアイデンティティを否定する。モハンティは、米国内の権力構造と植民地主義との間の相互分裂性と関係性のパフォーマンスと、この植民地の権力構造の歴史との間でどのようにアイデンティティを横断して機能させるかについて疑問を呈している。[61] この均質性と交差する同一性の欠如は、インドの女性が社会構造の中でどのようにフェミニズムを実践しているか、また西欧や他の非西欧諸国とは異なる植民地化の継続的影響を越えているインドのフェミニズムを通して理解することができる。

This is elaborated on by Christine Bose, who discusses a global use of intersectionality which works to remove associations of specific inequalities with specific institutions, while showing that these systems generate intersectional effects. She uses this approach to develop a framework that can analyze gender inequalities across different nations and differentiates this from an approach (the one that Mohanty was referring to) which, one, paints national-level inequalities as the same and, two, differentiates only between the global North and South. This is manifested through the intersection of global dynamics like economics, migration, or violence, with regional dynamics, like histories of the nation or gendered inequalities in education and property education.[65]

これはChristine Boseによって詳述されており、彼は特定の機関との特定の不平等の関連を除去するために働く交差性のグローバルな使用について議論している。///一方、これらのシステムが横断的効果を生み出すことを示している。彼女はこのアプローチを用いて、異なる国家間のジェンダー不平等を分析することができる枠組みを構築し、これを、1つは国家レベルの不平等を同じものとして描き、もう1つは世界の北と南だけを区別するアプローチ(モハンティが言っていたのは)と区別する。このことは、経済、移住、暴力などの地球規模の力学と、国の歴史や教育や財産教育におけるジェンダーの不平等などの地域的な力学が交わることで明らかになる。[62]

There is an issue globally with the way the law interacts with intersectionality, for example, the UK's legislation to protect workers rights has a distinct issue with intersectionality. Under the Equality Act 2010, the things that are listed as 'protected characteristics' are "age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage or civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation".[66] "Section 14 contains a provision to cover direct discrimination on up to two combined grounds—known as combined or dual discrimination. However, this section has never been brought into effect as the government deemed it too 'complicated and burdensome' for businesses."[67] This demonstrates a systematic neglect of the issues that intersectionality presents, because the UK courts have explicitly decided not to cover intersectional discrimination in their courts.

例えば、労働者の権利を保護するための英国の法律は、明確な問題を抱えている。2010年の平等法では、「保護特性 」とされているものは「年齢、障害、性別の再割り当て、結婚または市民パートナーシップ、妊娠および出産、人種、宗教または信条、性別および性的指向」である。[63] 「第14条は、最大2つの複合事由 (複合又は二重差別として知られる) についての直接差別を対象とする規定を含んでいる。しかし、この条項は、政府が企業にとっても「複雑で厄介な 」と見なしたため、施行されたことはありません。」 [64] これは、英国の裁判所が明確に自裁判所における部門間差別を対象としないと決定していることから、部門間差別がもたらす問題を組織的に無視していることを示している。

Transnational intersectionality

[編集]Third World feminists and transnational feminists criticize intersectionality as a concept emanating from WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic)[68] societies that unduly universalizes women's experiences.[69][70] Third world feminists have worked to revise Western conceptualizations of intersectionality that assume all women experience the same type of gender and racial oppression.[69][71] Shelly Grabe coined the term "transnational intersectionality" to represent a more comprehensive conceptualization of intersectionality. Grabe wrote, "Transnational intersectionality places importance on the intersections among gender, ethnicity, sexuality, economic exploitation, and other social hierarchies in the context of empire building or imperialist policies characterized by historical and emergent global capitalism."[72] Both Third World and transnational feminists advocate attending to "complex and intersecting oppressions and multiple forms of resistance".[69][71]

国境を越えた横断編集 第三世界のフェミニストや国際的フェミニストたちは、女性の経験を不当に普遍化する奇妙な(西欧諸国、教育、工業化、富裕、民主主義)社会 [65] から生まれた概念として、相互分離性を批判している。[66] [67] 第三世界のフェミニストたちは、すべての女性が同じタイプのジェンダーと人種的抑圧を経験していると仮定した、西洋における相互分離の概念化を修正するために活動してきた。[66] [68] シェリー・グレイブは、交差性のより包括的な概念化を表すために「国境を越えた国家間の分断」という用語を作り出した。Grabeは「国境を越えた横断性は、歴史的で創発的なグローバル資本主義によって特徴づけられる帝国構築や帝国主義政策の文脈において、ジェンダー、民族、セクシャリティ、経済的搾取、その他の社会階層の間の交差を重要視する。」と書いている [69] 。第三世界と多国籍フェミニストの両者とも、「複雑で交差する圧迫と複数の形態の抵抗」に参加することを提唱している。[66] [68]

Social work

[編集]In the field of social work, proponents of intersectionality hold that unless service providers take intersectionality into account, they will be of less use for various segments of the population, such as those reporting domestic violence or disabled victims of abuse. According to intersectional theory, the practice of domestic violence counselors in the United States urging all women to report their abusers to police is of little use to women of color due to the history of racially motivated police brutality, and those counselors should adapt their counseling for women of color.[73]

ソーシャルワーク編集 ソーシャルワークの分野では、サービス提供者が交差性を考慮しない限り、ドメスティック・バイオレンスや虐待の障害者被害者のような、様々な層の人々にとって、それらはあまり役に立たないだろうと、交差性の支持者は主張する。横断的な理論によれば、米国では、すべての女性に加害者を警察に報告するよう求めるドメスティックバイオレンスのカウンセラーの慣行は、人種的動機に基づく警察の残虐行為の歴史のために有色人種の女性にはほとんど役に立たず、これらのカウンセラーは、有色人種の女性に対するカウンセリングを適応させるべきである。[70]

Women with disabilities encounter more frequent domestic abuse with a greater number of abusers. Health care workers and personal care attendants perpetrate abuse in these circumstances, and women with disabilities have fewer options for escaping the abusive situation.[74] There is a "silence" principle concerning the intersectionality of women and disability, which maintains an overall social denial of the prevalence of abuse among the disabled and leads to this abuse being frequently ignored when encountered.[75] A paradox is presented by the overprotection of people with disabilities combined with the expectations of promiscuous behavior of disabled women.[74][75] This leads to limited autonomy and social isolation of disabled individuals, which place women with disabilities in situations where further or more frequent abuse can occur.[74]

障害のある女性は、より多くの虐待者とともに、より頻繁に家庭内虐待を受ける。このような状況では、医療従事者や介護職員が虐待を行っており、障害のある女性は虐待の状況から逃れるための選択肢が少ない。[71] 女性と障害の交差性に関する「沈黙」原則があり、障害者の間での虐待の蔓延に対する全体的な社会的否定を維持し、このような虐待に遭遇した際にしばしば無視される結果となっている。[72] 障害者の過剰な保護と、障害のある女性の乱交行動への期待が相まって、パラドックスが生じている。[71] [72] これにより、障害者の自律性と社会的孤立が制限され、障害のある女性はさらなる虐待や頻繁な虐待が起こりうる状況に置かれることになる。[71]

Criticism

[編集]方法とイデオロギー

[編集]According to political theorist Rebecca Reilly-Cooper intersectionality relies heavily on standpoint theory, which has its own set of criticisms. Intersectionality posits that an oppressed person is often the best person to judge their experience of oppression; however, this can create paradoxes when people who are similarly oppressed have different interpretations of similar events. Such paradoxes make it very difficult to synthesize a common actionable cause based on subjective testimony alone.[76] Other narratives, especially those based on multiple intersections of oppression, are more complex.[77] Davis (2008) asserts that intersectionality is ambiguous and open-ended, and that its "lack of clear-cut definition or even specific parameters has enabled it to be drawn upon in nearly any context of inquiry".[78]

政治理論家のレベッカ・レイリー=クーパーによると、相互分離性は立場理論に大きく依存しており、それには独自の批判がある。交差性は、抑圧された人が抑圧の経験を判断するのにしばしば最良の人であると仮定する;しかし、同じように抑圧されている人々が同じような出来事について異なる解釈をしている場合には、矛盾が生じることがある。このようなパラドックスは、主観的証言のみに基づいて共通の行動可能な原因を合成することを非常に困難にしている。[73] 他の物語、特に抑圧の多重交差に基づくものは、より複雑である。[74] Davis (2008) は、交差性はあいまいで終わりのないものであり、「明確な定義や特定のパラメータがないために、ほとんどどんな調査の文脈でもそれを利用することができた」と主張する。[75]

Rekia Jibrin and Sara Salem argue that intersectional theory creates a unified idea of anti-oppression politics that requires a lot out of its adherents, often more than can reasonably be expected, creating difficulties achieving praxis. They also say that intersectional philosophy encourages a focus on the issues inside the group instead of on society at large, and that intersectionality is "a call to complexity and to abandon oversimplification... this has the parallel effect of emphasizing 'internal differences' over hegemonic structures".[79][注釈 1]

Rekia JibrinとSara Salemは、横断的理論が反圧政政治の統一的な概念を生み出し、その支持者の多くを必要とし、多くの場合、合理的に予想される以上のものを必要とし、実践を達成することを困難にしていると論じている。また、部門間の哲学は社会全体ではなくグループ内の問題に焦点を当てることを奨励し、部門間性は「複雑さへの呼びかけと過度の単純化をやめること...これは、覇権主義的構造よりも「内部差異 」を強調する並行した効果を持つ」であるとも述べている。[76] [a]

Writing in the New Statesman, Helen Lewis adds that in emphasizing internal differences over hegemonic structures, and having complex and at times contradictory recommendations, it can create paralysis because it is not very accessible.[80]

ヘレン・ルイスは『New Statesman』の中で、覇権主義的な構造よりも内部の相違を強調し、複雑で時には矛盾した勧告をすることで、アクセスしにくいために麻痺を引き起こす可能性があると付け加えています。[77]

The moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt, in a speech at the American conservative think tank Manhattan Institute, criticized the theory by saying:

[In intersectionality] the binary dimensions of oppression are said to be interlocking and overlapping. America is said to be one giant matrix of oppression, and its victims cannot fight their battles separately. They must all come together to fight their common enemy, the group that sits at the top of the pyramid of oppression: the straight, white, cis-gendered, able-bodied Christian or Jewish or possibly atheist male. This is why a perceived slight against one victim group calls forth protest from all victim groups. This is why so many campus groups now align against Israel. Intersectionality is like NATO for social-justice activists.[81]Template:Primary inline

道徳心理学者のJonathan Haidt氏は、米国の保守系シンクタンクであるManhattan Instituteでの講演で、この理論を次のように批判した。

[交差性]抑圧の二値次元は、連動し、重なり合っているといわれる。アメリカは巨大な抑圧のマトリックスの一つと言われており、その犠牲者たちは個別に戦闘を行うことはできません。彼らは皆、共通の敵と戦うために団結しなければなりません。それは、抑圧のピラミッドの頂点に位置する集団です。真っ直ぐで、白人で、シスの性を持ち、強健なクリスチャンかユダヤ人、あるいは無神論者の男性です。1つの被害者グループを軽く見て、すべての被害者グループから抗議を呼び掛けるのはこのためである。これが現在、多くのキャンパスグループがイスラエルに反対している理由です。社会正義活動家にとって、国家間の分断はNATOのようなものだ。[78] [必要な非一次ソース]

Barbara Tomlinson is employed at the Department of Women's Studies at UC Santa Barbara and has been critical of the applications of intersectional theory. She has identified several ways in which the conventional theory has been destructive to the movement. She asserts that the common practice of using intersectionality to attack other ways of feminist thinking and the tendency of academics to critique intersectionality instead of using intersectionality as a tool to critique other conventional ways of thinking has been a misuse of the ideas it stands for. Tomlinson argues that in order to use intersectional theory correctly, intersectional feminists must not only consider the arguments but the tradition and mediums through which these arguments are made. Conventional academics are likely to favor writings by authors or publications with prior established credibility instead of looking at the quality of each piece individually, contributing to negative stereotypes associated with both feminism and intersectionality by having weaker arguments in defense of feminism and intersectionality become prominent based on renown. She goes on to argue that this allows critics of intersectionality to attack these weaker arguments, "[reducing] intersectionality's radical critique of power to desires for identity and inclusion, and offer a deradicalized intersectionality as an asset for dominant disciplinary discourses".[82]

バーバラ・トムリンソンは、カリフォルニア大学サンタバーバラ校の女性研究科で雇用されており、部門間理論の応用に批判的である。彼女は、従来の理論が運動に対して破壊的であったいくつかの方法を特定した。彼女は、他のフェミニストの考え方を攻撃するために交差性を利用する一般的な慣行や、他の従来の考え方を批判するためのツールとして交差性を利用するのではなく、交差性を批判する学者の傾向は、それが表す考え方の誤用であると主張する。トムリンソンは、部門間理論を正しく使用するためには、部門間フェミニストは、議論だけでなく、これらの議論が行われる伝統や媒体も考慮しなければならないと主張する。従来の学者は、個々の作品の質を個別に見るのではなく、事前に信頼性が確立された著者や出版物による著作を好む傾向があり、フェミニズムの擁護においてより弱い議論をすることによって、フェミニズムと横断性の両方に関連する否定的な固定観念に寄与し、有名に基づいて顕著になる。彼女は続けて、このことは、相互分離性の批判者がこれらの弱い議論を攻撃することを可能にすると主張している。

Sharon Goldman of the Israel-America Studies Program at Shalem College also criticized intersectionality on the basis of its being too simplistic. Goldman stipulates that many of the people championed by intersectionality truly are victims of oppression, but her reading of the ideology is that it favors the powerless over the powerful regardless of context. Any group that overcomes adversity, achieves independence, or defends itself successfully is seen as corrupt or imperialist by intersectionality adherents. The examples Goldman gives are American Jews who, inspired by the abject victimhood of the Holocaust, engaged in politics to successfully advance their ideas into the American mainstream. American Jews are not given the benefit of the doubt by intersectionality adherents because they proudly reject victimization.[83]

シャレム・カレッジの『イスラエル・アメリカ研究プログラム』のシャロン・ゴールドマン氏も、あまりにも単純すぎるという理由で、分離主義を批判した。ゴールドマン氏は、 「分断を支持する人々の多くは、実際には抑圧の犠牲者だ」 としながらも、 「状況にかかわらず、権力者より権力者を優先する」 と解釈した。逆境を克服し、独立を成し遂げ、自らをうまく守ろうとする集団は、党派間の支持者によって腐敗した、あるいは帝国主義者と見なされる。ゴールドマンが挙げている例はユダヤ系アメリカ人でホロコーストの惨めな犠牲者に触発されて政治に従事し自分たちの考えをアメリカの主流に押し上げることに成功したユダヤ人である。アメリカのユダヤ人は、被害者になることを誇りを持って拒否しているので、宗派を超えた支持者によって、疑いの利益を受けることはない。[80]

Lisa Downing argues that because intersectionality focuses too much on group identities, which can lead it to ignore the fact that people are individuals, not just members of a class. Ignoring this can cause intersectionality to lead to a simplistic analysis and inaccurate assumptions about how a person's values and attitudes are determined.[84]

Lisa Downing氏は、横断性はグループのアイデンティティに焦点を当てすぎているため、人々がクラスのメンバーではなく個人であるという事実を無視してしまう可能性があると主張している。これを無視すると、人の価値観や態度がどのように決定されているかについての単純な分析や不正確な仮定につながる可能性がある。[81]

心理学

[編集]Researchers in psychology have incorporated intersection effects since the 1950s[要実例]. These intersection effects were based on studying the lenses of biases, heuristics, stereotypes, and judgments. Psychologists have extended research in psychological biases to the areas of cognitive and motivational psychology. What is found, is that every human mind has its own biases in judgment and decision-making that tend to preserve the status quo by avoiding change and attention to ideas that exist outside one's personal realm of perception.[85] Psychological interaction effects span a range of variables, although person-by-situation effects are the most examined category. As a result, psychologists do not construe the interaction effect of demographics such as gender and race as either more noteworthy or less noteworthy than any other interaction effect. In addition, oppression can be regarded as a subjective construct when viewed as an absolute hierarchy. Even if an objective definition of oppression was reached, person-by-situation effects would make it difficult to deem certain persons or categories of persons as uniformly oppressed. For instance, black men are stereotypically perceived as violent, which may be a disadvantage in police interactions, but also as physically attractive,[86][87] which may be advantageous in romantic situations.[88]

心理学の研究者は、1950年代[必要な例]から交差効果を取り入れてきた。これらの交差効果は、バイアス、ヒューリスティックス、ステレオタイプ、および判断のレンズの研究に基づいていた。心理学者は、心理的バイアスの研究を認知心理学や動機付け心理学の分野にまで広げた。ここでわかっているのは、すべての人間の心には、判断や意思決定に独自のバイアスがあるということである。このバイアスは、自分の知覚領域の外に存在する考えに対する変化や注意を避けることによって、現状を維持しようとする傾向がある。[82] 心理学的相互作用効果は変数の範囲に及ぶが、状況による個人差効果が最も検討されているカテゴリーである。その結果、心理学者は性別や人種などの人口統計学的な相互作用効果を、他のいかなる相互作用効果よりも注目に値するか注目に値しないかのどちらかとして解釈しない。加えて、抑圧は、絶対的な階層として見ると、主観的な構成体とみなすことができる。抑圧の客観的な定義に到達したとしても、個別の状況に応じた効果があるために、特定の人物やカテゴリーの人々を一様に抑圧されているとは考えにくい。例えば、黒人男性はステレオタイプ的に暴力的だと認識され、警察とのやりとりでは不利かもしれないが、ロマンチックな状況では有利かもしれない肉体的に魅力的である [83] [84] 。[85]

Psychological studies have shown that the effect of multiplying "oppressed" identities is not necessarily additive, but rather interactive in complex ways. For instance, black gay men may be more positively evaluated than black heterosexual men, because the "feminine" aspects of gay stereotypes temper the hypermasculine and aggressive aspect of black stereotypes.[88][89]

心理学的研究によると、「抑圧された」アイデンティティを増殖させる効果は必ずしも相加的ではなく、むしろ複雑な形で相互作用的であることが示されている。例えば、ゲイのステレオタイプの「女性らしい」の側面が、黒人のステレオタイプの超男性的で攻撃的な側面を抑制するので、黒人のゲイの男性は黒人の異性愛者の男性より肯定的に評価されるかもしれない。[85] [86]

Alan Dershowitz, scholar of United States constitutional law and criminal law in answering a question on the criticism of Israel by intersectional movements, he stated that the concept of intersectionality is an oversimplification of reality that makes LGBT activists stand in solidarity with advocates of Sharia, even though Islamic law denies the rights of the former. He feels that identity politics does not evaluate ideas or individuals on the basis of the quality of their character. Dershowitz argues that in academia, intersectionality is taught with a large influence from antisemitism. He states that Jews are actually more liberal and supportive of equal rights than many other religious sects.[90]

米国憲法学者・刑法学者のアラン・デルショウィッツは、イスラム法がイスラエルの権利を否定しているにもかかわらず、LGBT活動家たちをシャリア支持者と連帯させている現実を単純化しすぎていると、地域間の運動によるイスラエル批判に答えている。彼は、アイデンティティ政治はアイデアや個人をその性格の質によって評価するものではないと感じている。デルショウィッツは、学界では、反ユダヤ主義の影響を大きく受けて、相互分離性が教えられていると主張する。実際、ユダヤ人は他の多くの宗派よりも自由で平等な権利を支持していると彼は言う。[87]

Writer and political pro-Israel activist Chloé Valdary considers intersectionality "a rigid system for determining who is virtuous and who is not, based on traits like skin color, gender, and financial status". Valdary also states:

Intersectionality's greatest flaw is in reducing human beings to political abstractions, which is never a tendency that turns out well—in part because it so severely flattens our complex human experience, and therefore fails to adequately describe reality. As it turns out, one can be personally successful and still come from a historically oppressed community—or vice versa. The human experience is complex and multifaceted and deeper than the superficial ways in which intersectionalists describe it.[91]

作家で親イスラエル派の活動家クロエ・バルダリーは、「肌の色、性別、財政状態などの特性に基づいて、誰が徳で、誰が徳でないかを決定するための厳格なシステム」と考えている。Valdary氏は次のように述べている。

交差性の最大の欠点は、人間を政治的抽象化することにありますが、それは決してうまくいく傾向ではありません。結局のところ、個人的には成功していても、歴史的に抑圧されたコミュニティの出身であったり、その逆であったりすることがある。人間の経験は複雑で多面的であり、横断主義者が表現する表面的な方法よりも深い。[88]

As zealotry 狂信として

[編集]Conservative en:political commentator en:Andrew Sullivan argues that the practice of intersectionality "manifests itself almost as a religion. It posits a classic orthodoxy through which all of human experience is explained—and through which all speech must be filtered."[92] en:David A. French, writer for the en:National Review, states that proponents of intersectionality are "zealots of a new religious faith" intending to fill a "religion-shaped hole in the human heart".[93]

保守政治評論家 アンドリュー・サリバンは、インターセクショナリティの実践は「ほとんど宗教として現れる。それは、人間のすべての経験が説明され、すべてのスピーチがフィルタリングされなければならない古典的な正統性を主張します。」と論じている [94] ナショナル・レビューのライター、デビッド・A.フレンチは、インターセクショナリティの支持者は「人間の心臓の宗教的な形をした穴」を満たそうと意図して「新しい宗教的信仰の狂信者」と述べている。[95]

参照

[編集]- en:Black feminism 黒人フェミニズム

- en:Caste カースト

- en:Humanism ヒューマニズム

- en:Identitarianism アイデンティティ主義

- en:Kyriarchy キリアー

- en:Oppression Olympics オリンピック

- en:Privilege (social inequality) 特権(社会的不平等)

- en:Standpoint theory スタンドポイント理論

- en:Transnational feminism 多国籍フェミニズム

- en:Triple oppression 三重の抑圧

- en:Womanism ウーマニズム

Notes

[編集]- ^ See hegemony and cultural hegemony.

References

[編集]- ^ a b c “What Does Intersectional Feminsim Actually Mean?”. International Women's Development Agency (May 11, 2018). 23 April 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。 Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Cooper, Brittney (1 February 2016). Disch, Lisa; Hawkesworth, Mary. eds (英語). Intersectionality. 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328581.013.20

- ^ Crenshaw, Kimberlé (英語), The urgency of intersectionality 2019年11月26日閲覧。

- ^ Cooper, Brittney (1 February 2016). Disch, Lisa; Hawkesworth, Mary. eds (英語). Intersectionality. 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328581.013.20

- ^ Crenshaw, Kimberlé (英語), The urgency of intersectionality 2019年11月26日閲覧。

- ^ Kimberlé Crenshaw (14 March 2016). Kimberlé Crenshaw – On Intersectionality – keynote – WOW 2016 (Video). Southbank Centre via YouTube. 2016年6月10日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年5月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, More than Two Decades Later”. 23 February 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。9 March 2019閲覧。

- ^ a b c Kimberlé Krenshaw (1989年). “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics”. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 13 May 2018時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。7 June 2020閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Kimberlé Crenshaw on intersectionality: 'I wanted to come up with an everyday metaphor that anyone could use'”. New Statesman. (2 April 2014). オリジナルの18 May 2018時点におけるアーカイブ。 2016年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Hooks, Bell (2014) [1984]. Feminist Theory: from margin to center (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781138821668

- ^ Davis, Angela Y. (1983). Women, Race & Class. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 9780394713519

- ^ Davis, Angela Y. (1983). Women, Race & Class. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 9780394713519

- ^ Thompson, Becky (Summer 2002). “Multiracial feminism: recasting the chronology of Second Wave Feminism”. Feminist Studies 28 (2): 337–360. doi:10.2307/3178747. JSTOR 3178747.

- ^ Fixmer-Oraiz, Natalie; Wood, Julia (2015). Gendered Lives: Communication, Gender, & Culture. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-1-305-28027-4

- ^ Grady, Constance (2018年3月20日). “The waves of feminism, and why people keep fighting over them, explained”. Vox. 5 April 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年5月7日閲覧。

- ^ Fixmer-Oraiz, Natalie; Wood, Julia (2015). Gendered Lives: Communication, Gender, & Culture. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-1-305-28027-4

- ^ a b McCall, Leslie (Spring 2005). “The complexity of intersectionality”. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 30 (3): 1771–1800. doi:10.1086/426800. JSTOR 10.1086/426800. Pdf.

- ^ Carastathis, Anna (2016). Leong, Karen J.. ed. Intersectionality: Origins, Contestations, Horizons. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803285552. JSTOR j.ctt1fzhfz8

- ^ Mueller, Ruth Caston (1954). “The National Council of Negro Women, Inc.”. Negro History Bulletin 18 (2): 27–31. ISSN 0028-2529. JSTOR 44175227.

- ^ Thompson, Becky (Summer 2002). “Multiracial feminism: recasting the chronology of Second Wave Feminism”. Feminist Studies 28 (2): 337–360. doi:10.2307/3178747. JSTOR 3178747.

- ^

Wiegman, Robyn (2012), "Critical kinship (universal aspirations and intersectional judgements) Archived 2017 at the Wayback Machine.", in Wiegman, Robyn, ed (2012). Object lessons. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. p. 244. ISBN 9780822351603

- Citing:

- Hull, Gloria T.; Bell-Scott, Patricia; Smith, Barbara (1982). All the women are White, all the Blacks are men, but some of us are brave: Black women's studies. Old Westbury, NY: Feminist Press. ISBN 9780912670928

- Citing:

- ^ Johnson, Amanda Walker (2017-10-02). “Resituating the Crossroads: Theoretical Innovations in Black Feminist Ethnography”. Souls 19 (4): 401–415. doi:10.1080/10999949.2018.1434350. ISSN 1099-9949.

- ^ Norman, Brian (2007). “'We' in Redux: The Combahee River Collective's Black Feminist Statement”. differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 18 (2): 104. doi:10.1215/10407391-2007-004.

- ^ Guy-Sheftall, Beverly (1995). Words of fire : an anthology of African-American feminist thought. New York: New Press. ISBN 9781565842564 7 May 2019閲覧。

- ^ King, Deborah K. (1988). “Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology”. Signs 14 (1): 42–72. doi:10.1086/494491. ISSN 0097-9740. JSTOR 3174661.

- ^ a b c d Buikema, Plate & Thiele, R., L.K. (2009). Doing Gender in Media, Art and Culture: A Comprehensive Guide to Gender Studies. Routeledge. pp. 63–65. ISBN 978-0415493833

- ^ Truth, Sojourner (2001). “"Speech at the Woman's Rights Convention, Akron, Ohio" (1851)”. 'Speech at the Woman's Rights Convention, Akron, Ohio' (1851). University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 144–146. doi:10.2307/j.ctt5hjqnj.28. ISBN 9780822979753

- ^ King, Deborah K. (1988). “Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology”. Signs 14 (1): 42–72. doi:10.1086/494491. ISSN 0097-9740. JSTOR 3174661.

- ^ Truth, Sojourner (2001). “"Speech at the Woman's Rights Convention, Akron, Ohio" (1851)”. 'Speech at the Woman's Rights Convention, Akron, Ohio' (1851). University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 144–146. doi:10.2307/j.ctt5hjqnj.28. ISBN 9780822979753

- ^ “Full text of 'Demarginalizing The Intersection of Race And Sex A Black Feminis'”. archive.org. 29 December 2018時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。23 August 2018閲覧。

- ^ Crenshaw, Kimberlé (1989). “Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics”. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 139–168. オリジナルの28 April 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。 2 June 2019閲覧。.

- ^ Thomas, Sheila; Crenshaw, Kimberlé (Spring 2004). “Intersectionality: the double bind of race and gender”. Perspectives Magazine (American Bar Association): p. 2. オリジナルの18 January 2012時点におけるアーカイブ。 14 June 2011閲覧。

- ^ a b c Crenshaw, Kimberlé (July 1991). “Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color”. Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. doi:10.2307/1229039. JSTOR 1229039.

- ^ Mann, Susan A.; Huffman, Douglas J. (January 2005). “The decentering of second wave feminism and the rise of the third wave”. Science & Society 69 (1): 56–91. doi:10.1521/siso.69.1.56.56799. JSTOR 40404229.

- ^ a b c d e Collins, Patricia Hill (March 2000). “Gender, black feminism, and black political economy”. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 568 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1177/000271620056800105.

- ^ Collins, Patricia Hill (2009) [1990], "Towards a politics of empowerment Archived 2 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine.", in Collins, Patricia Hill, ed (2009). Black feminist thought: knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 277. ISBN 9780415964722

- ^ Collins, Patricia H. (2015). “Intersectionality's definitional dilemmas”. Annual Review of Sociology 41: 1–20. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142.

- ^ Brah, Avtar; Phoenix, Ann (2004). “Ain't I A Woman? Revisiting intersectionality”. Journal of International Women's Studies 5 (3): 75–86. オリジナルの2 December 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。 1 December 2017閲覧。. Pdf. Archived 2 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Cooper, Anna Julia (2017) [1892], "The colored woman's office Archived 2 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine.", in Lemert, Charles, ed (2016). Social theory: the multicultural, global, and classic readings (6th ed.). Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 9780813350448

- ^ “Audre Lorde” (15 May 2020). Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ http://s18.middlebury.edu/AMST0325A/Lorde_The_Masters_Tools.pdf

- ^ This bridge called my back: writings by radical women of color (4th ed.). Albany: State University of New York (SUNY) Press. (2015). ISBN 9781438454382

- ^ hooks, bell (1981). Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. London & Boston, MA: Pluto Press South End Press. ISBN 978-0-86104-379-8

- ^ D'Agostino, Maria; Levine, Helisse (2011), "Feminist theories and their application to public administration", in Women in Public Administration: theory and practice. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. (2011). p. 8. ISBN 9780763777258

- ^ a b c Belleau, Marie-Claire (2007), "'L'intersectionalité': Feminisms in a divided world; Québec-Canada Archived 2 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine.", in Feminist Politics: identity, difference, and agency. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. (2007). pp. 51–62. ISBN 978-0-7425-4778-0

- ^ Patil, Vrushali (1 June 2013). “From Patriarchy to Intersectionality: A Transnational Feminist Assessment of How Far We've Really Come”. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38 (4): 847–867. doi:10.1086/669560. ISSN 0097-9740. JSTOR 10.1086/669560.

- ^ a b Browne, Irene; Misra, Joya (August 2003). “The intersection of gender and race in the labor market”. Annual Review of Sociology 29: 487–513. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100016. JSTOR 30036977. Pdf. Archived 2 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Ritzer, George; Stepinisky, Jeffrey (2013). Contemporary sociological theory and its classical roots: the basics (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 204–207. ISBN 9780078026782

- ^ Dudley, Rachel A. (2006). “Confronting the concept of intersectionality: the legacy of Audre Lorde and contemporary feminist organizations”. McNair Scholars Journal 10 (1): 5. オリジナルの1 December 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。 1 December 2017閲覧。.

- ^ a b c d e Collins, Patricia Hill (December 1986). “Learning from the outsider within: the sociological significance of black feminist thought”. Social Problems 33 (6): s14–s32. doi:10.2307/800672. JSTOR 800672.

- ^ Flores, "Creating Discursive Space," 142

- ^ Mann, Susan A.; Kelley, Lori R. (August 1997). “Standing at the crossroads of modernist thought: Collins, Smith, and the new feminist epistemologies”. Gender & Society 11 (4): 391–408. doi:10.1177/089124397011004002.

- ^ Hancock, Ange-Marie (June 2007). “Intersectionality as a normative and empirical paradigm”. Politics & Gender 3 (2): 248–254. doi:10.1017/S1743923X07000062.

- ^ Holvino, Evangelina (May 2010). “Intersections: The simultaneity of race, gender and class in organization studies”. Gender, Work & Organization 17 (3): 248–277. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00400.x.

- ^ a b Jones, Sandra J. (December 2003). “Complex subjectivities: class, ethnicity, and race in women's narratives of upward mobility”. Journal of Social Issues 59 (4): 803–820. doi:10.1046/j.0022-4537.2003.00091.x.

- ^ Kelly, Ursula A. (April–June 2009). “Integrating intersectionality and biomedicine in health disparities research”. Advances in Nursing Science 32 (2): E42–E56. doi:10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181a3b3fc. PMID 19461221.

- ^ a b Viruell-Fuentes, Edna A.; Miranda, Patricia Y.; Abdulrahim, Sawsan (December 2012). “More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health”. Social Science & Medicine 75 (12): 2099–2106. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037. PMID 22386617. Pdf. Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Ladson-Billings, Gloria; Tate IV, William F. (1995). “Toward a critical race theory of education (id: 1410)”. Teachers College Record 97 (1): 47–68. オリジナルの1 December 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。 1 December 2017閲覧。. Pdf. Archived 5 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lauderdale, Diane S. (February 2006). “Birth outcomes for Arabic-named women in California before and after September 11”. Demography 43 (1): 185–201. doi:10.1353/dem.2006.0008. PMID 16579214. Pdf. Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Cho, Sumi; Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams; McCall, Leslie (Summer 2013). “Toward a field of intersectionality studies: theory, applications, and praxis”. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38 (4): 785–810. doi:10.1086/669608. JSTOR 10.1086/669608.

- ^ Levine-Rasky, Cynthia (2011). “Intersectionality theory applied to whiteness and middle-classness”. Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture 17 (2): 239–253. doi:10.1080/13504630.2011.558377.

- ^ Lawson, Anna. European Union Non-Discrimination Law and Intersectionality : Investigating the Triangle of Racial, Gender and Disability Discrimination, edited by Dagmar Schiek, Routledge, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central

- ^ Analyzing Gender, Intersectionality, and Multiple Inequalities: Global, Transnational and Local Contexts, edited by Esther Ngan-ling Chow, and Tan Lin, Emerald Publishing Limited, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central

- ^ Mohanty, Chandra (Spring-Autumn 1984). “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses”. Boundary 2 12 (3): 333. doi:10.2307/302821. JSTOR 302821.

- ^ Bose, Christine E. (2012). “Intersectionality and Global Gender Inequality”. Gender and Society 26 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1177/0891243211426722. ISSN 0891-2432. JSTOR 23212241.

- ^ “Intersectionality: What is it and why does it matter for employers?”. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “Intersectionality: What is it and why does it matter for employers?”. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Henrich, J.; Heine, S. J.; Norenzayan, A. (2010). “The weirdest people in the world?”. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33 (2–3): 61–83. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999152X. PMID 20550733.

- ^ a b c Herr, R. S. (2014). “Reclaiming third world feminism: Or why transnational feminism needs third world feminism.”. Meridians 12: 1–30. doi:10.2979/meridians.12.1.1.

- ^ Kurtis, T.; Adams, G. (2015). “Decolonizing liberation: Toward a transnational feminist psychology”. Journal of Social and Political Psychology 3 (2): 388–413. doi:10.5964/jspp.v3i1.326. JSTOR 3178747.

- ^ a b Collins, L. H.; Machizawa, S.; Rice, J. K. (2019). Transnational Psychology of Women: Expanding International and Intersectional Approaches (1st ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ISBN 978-1-4338-3069-3

- ^ Grabe, S.; Else-Quest, N. M. (2012). “The role of transnational feminism in psychology: Complementary visions”. Psychology of Women Quarterly 36: 158–161. doi:10.1177/0361684312442164.

- ^ Bent-Goodley, Tricia B.; Chase, Lorraine; Circo, Elizabeth A.; Antá Rodgers, Selena T. (2010), "Our survival, our strengths: understanding the experiences of African American women in abusive relationships Archived 2 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine.", in Domestic violence intersectionality and culturally competent practice. New York: Columbia University Press. (2010). p. 77. ISBN 9780231140270

- ^ a b c Cramer, Elizabeth P.; Plummer, Sara-Beth (2010), "Social work practice with abused persons with disabilities Archived 2 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine.", in Domestic violence intersectionality and culturally competent practice. New York: Columbia University Press. (2010). pp. 131–134. ISBN 9780231140270

- ^ a b Chenoweth, Lesley (December 1996). “Violence and women with disabilities: silence and paradox”. Violence Against Women 2 (4): 391–411. doi:10.1177/1077801296002004004.

- ^ Reilly-Cooper, Rebecca (15 April 2013). “Intersectionality and identity politics”. More Radical With Age. 2 November 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。23 June 2017閲覧。

- ^ Kofi Bright, Liam; Malinsky, Daniel; Thompson, Morgan (January 2016). “Causally interpreting intersectionality theory”. Philosophy of Science 18 (1): 60–81. doi:10.1086/684173. Pdf. Archived 22 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Davis, Kathy (April 2008). “Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful”. Feminist Theory 9 (1): 67–85. doi:10.1177/1464700108086364.

- ^ Jibrin, Rekia; Salem, Sara (2015). “Revisiting intersectionality: reflections on theory and praxis”. Trans-Scripts: An Interdisciplinary Online Journal in the Humanities and Social Sciences 5. オリジナルの27 May 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。 1 December 2017閲覧。. Pdf. Archived 19 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lewis, Helen (20 February 2014). “The uses and abuses of intersectionality”. New Statesman. オリジナルの8 June 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。 23 June 2017閲覧。

- ^ Jonathan Haidt (17 December 2017). “The Age of Outrage” (英語). City Journal. オリジナルの6 March 2018時点におけるアーカイブ。 6 March 2018閲覧。

- ^ Tomlinson, Barbara (Summer 2013). “To Tell the Truth and Not Get Trapped: Desire, Distance, and Intersectionality at the Scene of Argument”. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38 (4): 993–1017. doi:10.1086/669571.

- ^ Goldman, Sharon. "Jews Must Not Embrace Powerlessness." Archived 27 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Commentary. February 2019. 26 February 2019.

- ^ Downing, Lisa. "The body politic: Gender, the right wing and ‘identity category violations’." French Cultural Studies 29, no. 4 (2018): 367-377.

- ^ Gorrell, Michael Gorrell (2011). “Combining NetLibrary E-books with the EBSCOhost Platform”. Information Standards Quarterly 23 (2): 31. doi:10.3789/isqv23n2.2011.07. ISSN 1041-0031.

- ^ Lewis, Michael B. (9 February 2012). “A facial attractiveness account of gender asymmetries in interracial marriage”. PLOS ONE 7 (2): e31703. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...731703L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031703. PMC 3276508. PMID 22347504.

- ^ Lewis, Michael B. (January 2011). “Who is the fairest of them all? Race, attractiveness and skin color sexual dimorphism”. Personality and Individual Differences 50 (2): 159–162. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.018.

- ^ a b Pedulla, David S. (March 2014). “The positive consequences of negative stereotypes: race, sexual orientation, and the job application process”. Social Psychology Quarterly 77 (1): 75–94. doi:10.1177/0190272513506229.

- ^ Remedios, Jessica D.; Chasteen, Alison L.; Rule, Nicholas O.; Plaks, Jason E. (November 2011). “Impressions at the intersection of ambiguous and obvious social categories: Does gay + Black = likable?”. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47 (6): 1312–1315. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.015. hdl:1807/33199.

- ^ Frommer, Rachel (28 September 2017). “Alan Dershowitz derides theory of intersectionality in Columbia lecture”. The Washington Free Beacon. オリジナルの7 October 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。 6 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ Valdary, Chloé. "What Farrakhan Shares With the Intersectional Left" Archived 29 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Tablet Magazine. 26 March 2018. 28 March 2018.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (March 10, 2017). “Is Intersectionality a Religion?” (英語). Intelligencer (New York Magazine). オリジナルの17 April 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。 April 17, 2019閲覧。

- ^ French, David A. (March 6, 2018). “Intersectionality, the Dangerous Faith”. National Review. オリジナルのMarch 7, 2018時点におけるアーカイブ。 April 17, 2019閲覧。

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (March 10, 2017). “Is Intersectionality a Religion?” (英語). Intelligencer (New York Magazine). オリジナルの17 April 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。 April 17, 2019閲覧。

- ^ French, David A. (March 6, 2018). “Intersectionality, the Dangerous Faith”. National Review. オリジナルのMarch 7, 2018時点におけるアーカイブ。 April 17, 2019閲覧。

External links

[編集]- "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics", by Kimberlé Crenshaw, 1989

- Black Feminist Thought in the Matrix of Domination

- Collins, Patricia Hill (1990年). “Black Feminist Thought”. Women of Color Web. 11 December 2006時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。 Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- A Brief History of Black Feminist Thought

- McCarthy, Allison. “The Intersectional Feminist”. Girl w/ Pen. 15 November 2012時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。 Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- Intersectionality 101

en:Category:Feminist theory en:Category:Intersectional feminism en:Category:Social constructionism