利用者:加藤勝憲/基金(現在の日本語版では扱っている概念の範囲が狭いので拡張するため)

基金とは、創設者や寄付者の意思に基づき、特定の目的のために、現金、金融商品、不動産、その他の財産を管理し、多くの場合、無期限に永続させるための仕組みで、法的に規制される[1]。基金は、インフレ調整後の元本や「コーパス」の価値を維持しながら、毎年、慎重な支出方針に基づいて資金の一部を使うことができる(場合によっては使わなければならない)ように構成されていることが多い。

基金は、非営利団体、慈善財団、または私立財団のいずれかとして管理・運営されることが多く、善良な目的のために活動しているものの、公益法人として認められない場合がある。また、寄付を行う団体や目的から独立した信託として設立されることもある。

一般的に寄付を管理する機関には、学術機関(大学、私立学校など)、文化機関(博物館、図書館、劇場など)、サービス機関(病院、老人ホーム、赤十字など)、宗教団体(教会、シナゴーグ、モスクなど)がある。

米国の場合

[編集]私的な寄付は、世界で最も裕福な団体の一つであり、特に私立の高等教育基金が有名である。ハーバード大学の基金(評価額532億ドル2021年現在)[3]は世界最大の学術基金である[4][5]。 ビル・アンド・メリンダ・ゲイツ財団は、基金額468億ドル2018年12月31日現在で2019年現在最も裕福な民間財団の1つだ[6][7]。

Private endowments are some of the wealthiest entities in the world, notably private higher education endowments. Harvard University's endowment (valued at $53.2 billion 2021年現在[update])[3] is the largest academic endowment in the world.[4][5] The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is one of the wealthiest private foundations as of 2019 with endowment of $46.8 billion 2018年12月31日現在[update].[6][7]

Types

[編集]米国では、ほとんどの民間基金が「統一機関投資家資金管理法」(Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act)に準拠しており、その一部は寄付者の意図に基づいて、基金の元本と収益に課される制約を定義するのに役立っています。米国における寄付は、一般的に以下の4つの方法で分類される[1]。

Most private endowments in the United States are governed by the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act which is based in part on the concept of donor intent that helps define what restrictions are imposed on the principal and earnings of the fund. Endowments in the United States are commonly categorized in one of four ways:[1]

- Unrestricted endowment can be used in any way the recipient chooses to carry out its mission.

- Term endowment funds stipulate that all or part of the principal may be expended only after the expiration of a stated period of time or occurrence of a specified event, depending on donor wishes.

- Quasi endowment funds are designated endowments by an organization's governing body rather than by the donor. Therefore both the principal and the income may be accessed at the organization's discretion. Quasi endowment funds are still subject to any other donor restrictions or intent.[8]

- Restricted endowments ensure that the original principal, inflation-adjusted, is held in perpetuity and prudent spending methods should be applied in order to avoid the erosion of corpus over reasonable time frames. Restricted endowments may also facilitate additional donor's requirements.

Restrictions and donor intent

[編集]寄付金収入は、寄付者によって様々な目的のために制限されることがある。特定の主題に限定された寄付講座や奨学金制度は一般的であり、寄付者がペットの扶養のためだけに信託資金を提供する場合もある[9][10] 。 裁判所は、寄贈者の意図に「可能な限り近い」代替案を見出すことを意味するサイ・プレと呼ばれる教義に基づき、制限付き寄付金の用途を変更することができる[11]。

Endowment revenue can be restricted by donors to serve many purposes. Endowed professorships or scholarships restricted to a particular subject are common; in some places a donor could fund a trust exclusively for the support of a pet.[9][10] Ignoring the restriction is called "invading" the endowment.[11] But change of circumstance or financial duress like bankruptcy can preclude carrying out the donor's intent. A court can alter the use of restricted endowment under a doctrine called cy-près meaning to find an alternative "as near as possible" to the donor's intent.[11]

歴史

[編集]

最古の寄附講座は、ローマ皇帝でストア派の哲学者マルクス・アウレリウスがAD176年にアテネに設立した。アウレリウスは、哲学の主要な学派に1つずつ寄付講座を設けた: プラトン主義、アリストテレス主義、ストア主義、エピクロス主義である。その後、帝国の他の主要都市にも同様の寄付講座が設置された[12][13]。

The earliest endowed chairs were established by the Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius in Athens in AD 176. Aurelius created one endowed chair for each of the major schools of philosophy: Platonism, Aristotelianism, Stoicism, and Epicureanism. Later, similar endowments were set up in some other major cities of the Empire.[12][13]

最古の大学はヨーロッパ、アジア、アフリカに設立された[14][15][16][17][18][19]。王子や君主による寄進と政府高官の養成という役割から、初期の地中海の大学はイスラムのマドラサに類似していたが、マドラサは一般的に小規模であり、マドラサ自体ではなく個々の教師が免許や学位を与えていた[20]。

The earliest universities were founded in Europe, Asia and Africa.[14][15][16][17][18][19] Their endowment by a prince or monarch and their role in training government officials made early Mediterranean universities similar to Islamic madrasas, although madrasas were generally smaller, and individual teachers, rather than the madrasa itself, granted the license or degree.[20]

ワクフ(アラビア語: وَقْف;[ˈwɑ])は、「hubous」(حُبوس)[21]または mortmain property(死すべき財産)としても知られ、イスラム法の類似概念である。 [22]寄付された資産は慈善信託によって保有されることもある。

Waqf (アラビア語: وَقْف; [ˈwɑqf]), also known as 'hubous' (حُبوس)[21] or mortmain property, is a similar concept from Islamic law, which typically involves donating a building, plot of land or other assets for Muslim religious or charitable purposes with no intention of reclaiming the assets.[22] The donated assets may be held by a charitable trust.

Ibn Umar reported, Umar Ibn Al-Khattab got land in Khaybar, so he came to the prophet Muhammad and asked him to advise him about it. The Prophet said, 'If you like, make the property inalienable and give the profit from it to charity.'" It goes on to say that Umar gave it away as alms, that the land itself would not be sold, inherited or donated. He gave it away for the poor, the relatives, the slaves, the jihad, the travelers and the guests. And it will not be held against him who administers it if he consumes some of its yield in an appropriate manner or feeds a friend who does not enrich himself by means of it.[23]—Ibn Ḥad̲j̲ar al-ʿAsḳalānī , Bulūg̲h̲ al-marām, Cairo n.d., no. 784

When a man dies, only three deeds will survive him: continuing alms, profitable knowledge and a child praying for him.[24]—Ibn Ḥad̲j̲ar al-ʿAsḳalānī , Bulūg̲h̲ al-marām, Cairo n.d., no. 78

最古のワクフィヤ(証文)は9世紀のもので、3つ目のものは10世紀初頭のもので、いずれもアッバース朝時代のものである。最も古い日付のワクフィヤは紀元876年にさかのぼり、複数巻のクルアーンに関するもので、イスタンブールのトルコ・イスラム芸術博物館に所蔵されている。もっと古いワクフィヤは、パリのルーヴル美術館が所蔵するパピルスで、年代は記されていないが、9世紀半ばのものと考えられている。

The two oldest known waqfiya (deed) documents are from the 9th century, while a third one dates from the early 10th century, all three within the Abbasid Period. The oldest dated waqfiya goes back to 876 CE, concerns a multi-volume Qur'an edition and is held by the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum in Istanbul. A possibly older waqfiya is a papyrus held by the Louvre Museum in Paris, with no written date but considered to be from the mid-9th century.

エジプトで最も古いワクフとして知られるのは、919年(アッバース朝時代)に財務官僚アブー・バクル・ムハッマド・ビン・アリー・アル・マダラーイによって設立されたビルカト・ハバシュと呼ばれる池とその周辺の果樹園で、その収益は水力発電所の運営と貧しい人々の給食に充てられることになっていた。インドでは、ワクフはムスリム社会の中で比較的一般的なものであり、中央ワクフ評議会によって規制され、1995年ワクフ法(1954年ワクフ法に代わるもの)によって管理されている。

The earliest known waqf in Egypt, founded by financial official Abū Bakr Muḥammad bin Ali al-Madhara'i in 919 (during the Abbasid period), is a pond called Birkat Ḥabash together with its surrounding orchards, whose revenue was to be used to operate a hydraulic complex and feed the poor. In India, wakfs are relatively common among Muslim communities and are regulated by the Central Wakf Council and governed by Wakf Act 1995 (which superseded Wakf Act 1954).

Modern college and university endowments

[編集]Academic institutions, such as colleges and universities, will frequently control an endowment fund that finances a portion of the operating or capital requirements of the institution. In addition to a general endowment fund, each university may also control a number of restricted endowments that are intended to fund specific areas within the institution. The most common examples are endowed professorships (also known as named chairs), and endowed scholarships or fellowships.

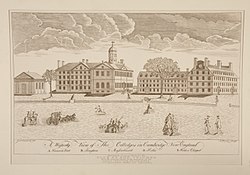

The practice of endowing professorships began in the modern European university system in England in 1502, when Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and grandmother to the future king Henry VIII, created the first endowed chairs in divinity at the universities of Oxford (Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity) and Cambridge (Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity).[25] Nearly 50 years later, Henry VIII established the Regius Professorships at both universities, this time in five subjects: divinity, civil law, Hebrew, Greek, and physic—the last of those corresponding to what are now known as medicine and basic sciences. Today, the University of Glasgow has fifteen Regius Professorships.

Private individuals also adopted the practice of endowing professorships. Isaac Newton held the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge beginning in 1669, more recently held by the celebrated physicist Stephen Hawking.[26]

In the United States, the endowment is often integral to the financial health of educational institutions. Alumni or friends of institutions sometimes contribute capital to the endowment. The use of endowment funding is strong in the United States and Canada but less commonly found outside of North America, with the exceptions of Cambridge and Oxford universities. Endowment funds have also been created to support secondary and elementary school districts in several states in the United States.

Endowed professorships

[編集]An endowed professorship (or endowed chair) is a position permanently paid for with the revenue from an endowment fund specifically set up for that purpose. Typically, the position is designated to be in a certain department. The donor might be allowed to name the position. Endowed professorships aid the university by providing a faculty member who does not have to be paid entirely out of the operating budget, allowing the university to either reduce its student-to-faculty ratio, a statistic used for college rankings and other institutional evaluations, or direct money that would otherwise have been spent on salaries toward other university needs. In addition, holding such a professorship is considered to be an honour in the academic world, and the university can use them to reward its best faculty or to recruit top professors from other institutions.[27]

Endowed faculty fellowships

[編集]An endowed faculty fellow is a position permanently paid for to recruit and retain new and/or junior (and above) professors who have already demonstrated superior teaching and research. The donor might be allowed to name the faculty fellowship. A faculty fellow appointment cultivates confidence and institutional loyalty, keeping the institution competitive over hiring and retention of talents.

Endowed scholarships and fellowships

[編集]An endowed scholarship is tuition (and possibly other costs) assistance that is permanently paid for with the revenue of an endowment fund specifically set up for that purpose. It can be either merit-based or need-based (the latter is only awarded to those students for whom the college expense would cause their family financial hardship) depending on university policy or donor preferences. Some universities will facilitate donors' meeting the students they are helping. The amount that must be donated to start an endowed scholarship can vary greatly.

Fellowships are similar, although they are most commonly associated with graduate students. In addition to helping with tuition, they may also include a stipend. Fellowships with a stipend may encourage students to work on a doctorate. Frequently, teaching or working on research is a mandatory part of a fellowship.

Charitable foundations

[編集]

Many might say that, by definition, philanthropy is about redistributing resources. Yet to truly embody this principle, philanthropy must move far beyond the 5% payout requirements for grants and distribute ALL of its power and resources. This includes spending down one’s endowment, investing in local and regional economic initiatives that build community wealth rather than investing in Wall Street, giving up decision-making power for grants, and, ultimately, turning over assets to community control.[29]—Justice Funders

A foundation (also a charitable foundation) is a category of nonprofit organization or charitable trust that will typically provide funding and support for other charitable organizations through grants, but may engage directly in charitable activities. Foundations include public charitable foundations, such as community foundations, and private foundations which are typically endowed by an individual or family. The term foundation though may also be used by organizations not involved in public grant-making.[30]

Fiduciary management

[編集]A financial endowment is typically overseen by a board of trustees and managed by a trustee or team of professional managers. Typically, the financial operation of the endowment is designed to achieve the stated objectives of the endowment.

In the United States, typically 4–6% of the endowment's assets are spent every year to fund operations or capital spending. Any excess earnings are typically reinvested to augment the endowment and to compensate for inflation and recessions in future years.[31] This spending figure represents the proportion that historically could be spent without diminishing the principal amount of the endowment fund.

Criticism and reforms

[編集]

Donor intent

[編集]The case of Leona Helmsley is often used to illustrate the downsides of the legal concept of donor intent as applied to endowments. In the 2000s, Helmsley bequested a multi-billion dollar trust to "the care and welfare of dogs".[32] This trust was estimated at the time to total 10 times more than the combined 2005 assets of all registered animal-related charities in the United States.

In 1914, Frederick Goff sought to eliminate the "dead hand" of organized philanthropy and so created the Cleveland Foundation: the first community foundation. He created a corporately structured foundation that could utilize community gifts in a responsive and need-appropriate manner. Scrutiny and control resided in the "live hand" of the public as opposed to the "dead hand" of the founders of private foundations.[33]

Economic downturn

[編集]Research published in the American Economic Review indicates that major academic endowments often act in times of economic downturn in a way opposite of the intention of the endowment. This behavior is referred to as endowment hoarding, reflecting the way that economic downturns often lead to endowments decreasing their payouts rather than increasing them to compensate for the downturn.[34]

Large U.S.-based college and university endowments, which had posted large, highly publicized gains in the 1990s and 2000s, faced significant losses of principal in the 2008 economic downturn. The Harvard University endowment, which held $37 billion in June 2008, was reduced to $26 billion by mid-2009.[35] Yale University, the pioneer of an approach that involved investing heavily in alternative investments such as real estate and private equity, reported an endowment of $16 billion as of September 2009, a 30% annualized loss that was more than predicted in December 2008.[36] At Stanford University, the endowment was reduced from $17 billion to $12 billion as of September 2009.[37] Brown University's endowment fell 27 percent to $2.04 billion in the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2009.[38] George Washington University lost 18% in that same fiscal year, down to $1.08 billion.[39]

In Canada, after the financial crisis in 2008, University of Toronto reported a loss of 31% ($545 million) of its previous year-end value in 2009. The loss is attributed to over-investment in hedge funds.[40]

Endowment repatriation

[編集]Critics like Justice Funders’ Dana Kawaoka-Chen call for "redistributing all aspects of well-being, democratizing power, and shifting economic control to communities.".[41] Endowment repatriation refers to campaigns that acknowledge the history of human and natural resource exploitation that is inherent to many large private funds. Repatriation campaigns ask for private endowments to be returned to the control of the people and communities that have been most affected by labor and environmental exploitation and often offer ethical frameworks for discussing endowment governance and repatriation.[29] [42]

After the Heron Foundation's internal audit of its investments in 2011 uncovered an investment in a private prison that was directly contrary to the foundation's mission, they developed and then began to advocate for a four-part ethical framework to endowment investments conceptualized as Human Capital, Natural Capital, Civic Capital, and Financial Capital.[43]

Another example is the Ford Foundation's co-founding of the independent Native Arts and Culture Foundation in 2007. The Ford Foundation provided a portion of the initial endowment after self-initiated research into the foundation's financial support of Native and Indigenous artists and communities. This results of this research indicated "the inadequacy of philanthropic support for Native arts and artists", related feedback from an unnamed Native leader that "[o]nce [big foundations] put the stuff in place for an Indian program, then it is not usually funded very well. It lasts as long as the program officer who had an interest and then goes away" and recommended that an independent endowment be established and that "[n]ative leadership is crucial".[44]

Divestment campaigns and impact investing

[編集]Another approach to reforming endowments is the use of divestment campaigns to encourage endowments to not hold unethical investments. One of the earliest modern divestment campaigns was Disinvestment from South Africa which was used to protest apartheid policies. By the end of apartheid, more than 150 universities divested of South African investments, although it is not clear to what extent this campaign was responsible for ending the policy.

A proactive version of divestment campaigns is impact investing, or mission investing which refers to investments "made into companies, organizations, and funds with the intention to generate a measurable, beneficial social or environmental impact alongside a financial return."[45] Impact investments provide capital to address social and environmental issues.

Endowment taxes

[編集]Generally, endowment taxes are the taxation of financial endowments that are otherwise not taxed due to their charitable, educational, or religious mission. Endowment taxes are sometimes enacted in response to criticisms that endowments are not operating as nonprofit organizations or that they have served as tax shelters, or that they are depriving local governments of essential property and other taxes.[46][47]

See also

[編集]- Foundation (nonprofit)

- Lists of institutions of higher education by endowment size

- in Canada

- in South Africa

- in the UK

- in the United States

- List of wealthiest charitable foundations

- Endowment tax

- Waqf

脚注

[編集]Further reading

[編集]- Newfield, Christopher (2008). Unmaking the public university: the forty-year assault on the middle class. Harvard University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-674-02817-3

External links

[編集]- Ford Foundation: A Primer for Endowment Grantmakers

- Dada, Kamil (February 1, 2008). “Congress investigates endowment”. Stanford Daily. オリジナルのJune 9, 2011時点におけるアーカイブ。

- 12 SMA for Financial Endowments

[[Category:教育費]] [[Category:未査読の翻訳があるページ]]

- ^ a b Kenton. “Endowment”. Investopedia. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “Harvard's Endowment Soars to $53.2 Billion, Reports 33.6% Returns”. The Harvard Crimson. October 14, 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。October 14, 2021閲覧。

- ^ “Harvard's Endowment Soars to $53.2 Billion, Reports 33.6% Returns” (英語). The Crimson (2021年10月14日). 2021年10月14日閲覧。

- ^ “Ivy League Endowments 2015: Princeton University On Top As Harvard Struggles With Low Investment Return”. Ibtimes.com (2010年5月10日). 2022年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Is Taxing Harvard, Yale and Stanford the Answer to Rising College Costs?”. Wall Street Journal. (4 May 2016)

- ^ “Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Consolidated Financial Statements”. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (2018年12月31日). 2020年1月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Foundation Fact Sheet” (英語). Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “Not-for-Profit Organizations”. AICPA Audit and Accounting Guide (American Institute of Certified Public Accountants): 367. (May 1, 2007).

- ^ Ashlea Ebelling (January 13, 2010). “Caring For Fido After You're Gone”. April 2, 2015時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。March 5, 2015閲覧。

- ^ Dhanya Ann Thoppil (February 19, 2015). “Monkey to Inherit House, Garden, Trust Fund – India Real Time”. February 22, 2015時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。March 5, 2015閲覧。

- ^ a b Patrick Sullivan (June 12, 2012). “Bankrupt But Endowed – The NonProfit TimesThe NonProfit Times”. April 2, 2015時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。March 5, 2015閲覧。

- ^ "Alexander of Aphrodisias > 1.1 Date, Family, Teachers, and Influence". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Lynch, John Patrick (1972). Aristotle's school; a study of a Greek educational institution. University of California Press. pp. 19––207; 213–216. ISBN 9780520021945

- ^ Rüegg, Walter: "Foreword. The University as a European Institution", in: A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. XIX–XX.

- ^ Hunt Janin: "The university in medieval life, 1179–1499", McFarland, 2008, ISBN 0-7864-3462-7, p. 55f.

- ^ de Ridder-Symoens, Hilde: A History of the University in Europe: Volume 1, Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. 47–55

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: "University" Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine., 2012, retrieved 26 July 2012)

- ^ Verger, Jacques: "Patterns", in: Ridder-Symoens, Hilde de (ed.): A History of the University in Europe. Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-54113-8, pp. 35–76 (35)

- ^ Civilization: The West and the Rest by Niall Ferguson, Publisher: Allen Lane 2011 - ISBN 978-1-84614-273-4

- ^ Pryds, Darleen (2000), “Studia as Royal Offices: Mediterranean Universities of Medieval Europe”, in Courtenay, William J.; Miethke, Jürgen; Priest, David B., Universities and Schooling in Medieval Society, Education and Society in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, 10, Leiden: Brill, pp. 96–98, ISBN 9004113517

- ^ Team. “تعريف و شرح و معنى حبوس بالعربي في معاجم اللغة العربية معجم المعاني الجامع، المعجم الوسيط ،اللغة العربية المعاصر ،الرائد ،لسان العرب ،القاموس المحيط - معجم عربي عربي صفحة 1” (英語). www.almaany.com. 2019年5月11日閲覧。

- ^ “What is Waqf - Awqaf SA”. awqafsa.org.za. 29 March 2018閲覧。

- ^ Ibn Ḥad̲j̲ar al-ʿAsḳalānī , Bulūg̲h̲ al-marām, Cairo n.d., no. 784. Quoted in Waḳf, Encyclopaedia of Islam.

- ^ Ibn Ḥad̲j̲ar al-ʿAsḳalānī , Bulūg̲h̲ al-marām, Cairo n.d., no. 783. Quoted in Waḳf, Encyclopaedia of Islam.

- ^ Lady Margaret's 500-year legacy Archived 2007-05-16 at the Wayback Machine. – University of Cambridge.

- ^ Bruen (May 1995). “A Brief History of The Lucasian Professorship of Mathematics at Cambridge University”. Robert Bruen. 24 August 2012時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。6 September 2012閲覧。

- ^ Cornell's "Celebrating Faculty" Website Archived 2005-05-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ “Grants”. Ford Foundation. 2014年5月14日閲覧。

- ^ a b “The Resonance Framework: Guiding Principals and Values”. Justice Funders. 19 May 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。19 May 2019閲覧。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "justicefunders.org"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ “What is a foundation | Foundations | Funding Resources | Knowledge Base | Tools”. GrantSpace.org (2013年6月18日). 2017年3月29日閲覧。

- ^ “SO NICELY ENDOWED!”. newsweek.com (31 July 2004). 14 April 2018閲覧。

- ^ Rosenwald, Julius (May 1929). “Principles of Public Giving”. The Atlantic Monthly.

- ^ “Cleveland Foundation 100 - Introduction” (英語). The Cleveland Foundation Centennial. 2019年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ Brown, Jeffrey R.; Dimmock, Stephen G.; Kang, Jun-Koo; Weisbenner, Scott J. (March 2014). “How University Endowments Respond to Financial Market Shocks: Evidence and Implications”. American Economic Review (American Economic Association) 104 (3): 931–962. doi:10.1257/aer.104.3.931.

- ^ Harvard fund loses $11B, a September 11, 2009 article from the Boston Herald Archived September 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Yale Endowment Down 30% Archived 2018-04-14 at the Wayback Machine., a September 10, 2009 article from The Wall Street Journal

- ^ Stanford University endowment loses big Archived 2009-09-06 at the Wayback Machine., a September 3, 2009 article from the San Francisco Chronicle

- ^ “Politics”. Bloomberg.com. 14 April 2018閲覧。

- ^ GW endowment drops 18 percent Archived August 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine., an August 27, 2009 article from The GW Hatchet

- ^ Burrows, Malcom D. (2010). “The End of Endowments?”. The Philanthropist 23 (1): 52–61.

- ^ “What Do Our Times Require? Funders Propose a Philanthropic "Green New Deal"”. Nonprofit Quarterly. (March 12, 2019).

- ^ “Linden Endowment Repatriation Broadside v1.3”. 19 May 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。19 May 2019閲覧。

- ^ “Introduction to Net Contribution”. Heron Foundation. 19 May 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。19 May 2019閲覧。

- ^ “Native Arts and Cultures: Research, Growth and Opportunities for Philanthropic Support”. Ford Foundation (2010年). 2019年5月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。13 May 2019閲覧。

- ^ “2017 Annual Impact Investor Survey”. The Global Impact Investing Network. 2016年9月2日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年3月14日閲覧。

- ^ “Ways and Means Questions Nonprofit Hospitals' Tax Status”. The Commonwealth Fund 1 East 75th Street, New York, NY. 2006年10月4日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年1月22日閲覧。

Jill Horwitz (2005年5月26日). “Testimony Before House Ways and Means Committee”. 2016年3月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。 Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。 - ^ He (October 4, 2005). “Cambridge Seeks to Tax Earnings on Endowment”. Volume 125, Number 44. The Tech. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。