利用者:安息香酸/砂場2

|

ここは安息香酸さんの利用者サンドボックスです。編集を試したり下書きを置いておいたりするための場所であり、百科事典の記事ではありません。ただし、公開の場ですので、許諾されていない文章の転載はご遠慮ください。

登録利用者は自分用の利用者サンドボックスを作成できます(サンドボックスを作成する、解説)。 その他のサンドボックス: 共用サンドボックス | モジュールサンドボックス 記事がある程度できあがったら、編集方針を確認して、新規ページを作成しましょう。 |

en:Fifth Crusadeのoldid=1234167398版をコピペ

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

第5回十字軍(1217年9月-1221年8月29日)[1]とは、聖地エルサレムの奪還とそれ先立ちアイユーブ朝スルタンアル・アーディル支配下のエジプトの制圧を目標とした13世紀の十字軍遠征である。

第4回十字軍が失敗に終わったのち、ローマ教皇インノケンティウス3世は再び十字軍遠征をヨーロッパ中に呼び掛け、ハンガリー王アンドラーシュ2世やオーストリア公レオポルト6世が十字軍を組織した。それから程なくして、エルサレム王位保持者ジャン・ド・ブリエンヌが十字軍に参加した。その後、1217年後半にかけて十字軍はシリア出遠征を行ったが、芳しい結果は得られず、アンドラーシュ2世は十字軍を離脱した。しかしその後、聖職者オリヴァー・ド・パーダーボルン率いるドイツ軍団とホラント伯ウィレム1世率いるオランダ人・フラマン人・フリース人混成軍がアッコに到着し十字軍に加勢した。またここで、教皇特使として枢機卿ペラギオ・ガルヴァニが到着した。ペラギオは十字軍の事実上のリーダーとなり、ジャンやテンプル騎士団・ホスピタル騎士団・チュートン騎士団の団長らの支援を受けて十字軍を率いることとなった。なお、1215年に十字軍の誓いをかけた神聖ローマ皇帝フリードリヒ2世は、約束通りにこの遠征に実際に参加することはなかった。

1218年から19年にわたって実施されたダミエッタ包囲戦で十字軍はナイル川河口部分の港湾都市ダミエッタを占領することに成功し、その後2年間にわたりその港を占領し続けた。アイユーブ朝スルタンのアル・カーミルは十字軍に対して講和を求め、その見返りにエルサレムを十字軍に割譲するという条件を提示した。これは十字軍に大して非常に魅力的な条件であったが、この条約はペラギオによって一蹴されてしまった。十字軍は1221年7月、カイロに向けて進軍を開始し、マンスーラに建つアル・カーミルの砦に攻めかかった。戦闘はムスリム側が有利に進み、十字軍は最終的にアイユーブ朝に対して降伏した。講和条約ではダミエッタの放棄並びにエジプトからの立ち退きが条件として課された。そして1221年9月、十字軍は目標を果たすことなく終結した[要出典]。

背景

[編集]1212年、在位14年目を迎えていたローマ教皇インノケンティウス3世は第4回十字軍での失態と聖地奪還がいまだ実現しないこと、並びに当時進行中であった同じキリスト教国に対する十字軍遠征、そして少年十字軍への人気の集まり様に落胆・失望していた。また、第4回十字軍を経てコンスタンティノープルにはラテン帝国が樹立され、同市にラテン・コンスタンティノープル総大司教ヴェネチア人のトマス・モロシニがラテン・コンスタンティノープル総大司教に任命されたが、インノケンティウス3世はトマス大司教が教会法に基づかない方法で任命されているとして、トマスと対立を深めていた[2]。

また、当時のヨーロッパ情勢もまた、混乱を極めていた。まず、神聖ローマ皇帝フィリップはドイツ諸侯オットー・ヴォン・ブラウンシュヴァイクと対立しており身動きが取れない状況であった。教皇はフィリップとオットーの仲介・対立解消を試みたが、この試みは1208年6月21日のフィリップ帝暗殺事件で水泡に帰した。加えて、オットー4世として皇帝に就任したオットーは軍を率いてイタリアに進軍し教皇と対立したことで、インノケンティウス3世から破門宣告を受けた。フランス王国でも状況は混乱していた。フランス王国はアルビジョワ十字軍の主力として遠征に加わっており、またイングランド王ジョン欠地王とも争いを抱えていた。そして後者とは1213年-1214年に戦争戦争となった。シチリア王国は国王ハインリヒ(7世)がまだ幼く、スペイン諸国はムワッヒド朝に対する十字軍で忙殺されていた。つまるところ、この頃のヨーロッパでは誰も新たな遠征を望んでいなかったのである[3]。

フランス諸侯ジャン・ド・ブリエンヌはエルサレム王族マリー・ド・モンフェラートとの結婚を経てエルサレム王に就任しており、エルサレムをよく統治していた。1212年、彼らの娘イザベラ2世が誕生から程なくしてエルサレム女王に即位し、ジャンは摂政として王国を支えた。またこの頃、主要な十字軍国家の1つ:アンティオキア公国はアンティオキア公ボエモン3世の崩御によって1201年から1219年まで続けられたアンティオキア公継承戦争の真っただ中であり、国力がそがれる一方であった[4]。

ジャン・ド・ブリエンヌが1210年にアッコに現れる以前、聖地在住の諸侯達はアイユーブ朝との休戦条約の延長を望んでいなかった。しかしアッコに来着したジャンはアイユーブ朝スルタン(アル・アディール)と条約の延長を取り決め、条約は1217年まで延長された。そして同時に、ムスリムが精強で砦や城砦の補強を進めているのを確認したジャンは教皇に対して軍事的支援を要請した。シリア地域に展開していたフランク人騎士たちは皆ヨーロッパに帰還してしまっており、聖地にはまともな兵力が残されていなかったためである。十字軍遠征を行うためにはヨーロッパからの遠征軍の派遣が欠かせなかったのである[5]。

インノケンティウス3世は、エルサレムをキリスト教の支配下に取り戻すという目標を忘れることなく、そのような聖地への十字軍を新たに実行することを望んでいた。また、1212年に少年少女が中心となった十字軍が実行され悲劇的な結末を迎えるという事件が起きていたが、それは彼を新たな遠征へ掻き立てるだけであった。そしてインノケンティウスはこの悲劇から「子供たちが我々を恥じ入らせている。私たちが眠っている間に、彼らは喜んで聖地を征服しに出発するのだ」という教訓を得ていたのである[6]。

十字軍に向けて

[編集]1213年4月、十字軍遠征をヨーロッパじゅうに呼び掛けるべく教皇インノケンティウス3世は教皇勅書( en:Quia maior)を発布した[7]。勅書発布後の1215年、公会議においてAd Liberandam,という取り決めがなされた。この公会議ではエルサレム奪還のための新たな取り組みの始動が決められ、その後1世紀続くことになる十字軍の規範が確立された[8]。

フランス国内での十字軍への参加を呼び掛ける説法は、インノケンティウス3世の旧友で勅使ロベール・ド・クルソンが担った。ロベールの説法はうまくいかず、現地の聖職者から「自領への侵略」として激しい反発に直面し、加えてフランス王フィリップ2世も聖職者らの意見を支持した。ロベールの状況を見たインノケンティウス3世は彼の熱意が裏目に出ていることを理解した。そして1215年11月11日、教皇は第4ラテラン公会議を開始した[9]。公会議にはフランス国内の多くの高位聖職者が参加し、たまりたまった不平不満をぶちまけた。教皇は勅使らの無思慮な行動に対して謝罪を行った。結果、1217年にランス大司教オーブリーやリモージュ司教・バイユー司教などを指導者とするフランス諸侯軍の十字軍参加が取り決められたが、その数は非常に少なくドイツ・ハンガリー部隊の構成軍としてしぶしぶ従軍することとなった[10]。

公会議によって、インノケンティウス3世は聖地奪還を広く呼びかけたが、彼は第1回十字軍がそうであるべきであったように、十字軍遠征団を教皇の指揮下に置くことを望んでいた。これはヴェネツィア共和国が十字軍を牛耳ったことで失敗に終わってしまった第4回十字軍と同じ轍を踏むのを避けるためであった。教皇は1217年7月1日にブリンディジ・メッシーナで出陣する十字軍と合流する計画を立て、また十字軍が船や武器を確実に確保できるようにムスリムとの取引を禁止する勅書(1179年発布)を延長した。またすべての十字軍参加者には贖宥状が渡され、また実際に参加できない者でも遠征費の支援をしたものにも与えられた[11] 。

また、教皇はジャン・ド・ブリエンヌに対して、使節としてフランスを訪ねていたラテン・エルサレム大司教ラウール(en:Raoul of Merencourt)の帰国に同行し護衛をするよう命じた。またこれに際して、ジャンと対立していたアルメニア王レヴォン1世・キプロス王ユーグ1世(エルサレムへの道中に経由する地域の国)に対してジャンと講和するよう命じた[12]。

1216年7月16日、インノケンティウス3世が崩御し、その翌週にホノリウス3世が教皇に就任した。彼の任期初期における職務はこの十字軍遠征が大きな割合を占めた[13]。翌年、ホノリウス3世はピエール2世・ド・クルトネーをラテン皇帝に戴冠したが、ピエールはエピロス専制侯国に対する遠征中にエピロス軍によって捕縛され、幽閉中に亡くなった。

ロベール・ド・クルソンは指導者としてフランス艦隊に派遣され、新たに選出された教皇勅使ペラージョ・ガルヴァーニの下で任務に就いた[14]。また、第4回十字軍の参加経験があるオータン司教ゴーティエ2世も十字軍と共に再び聖地へと向かった[15]。また、ベルギーの聖人Marie of Oigniesに感化され1210年以降アルビジョワ十字軍に対する説教活動を行っていたフランス人聖職者Jacques de Vitryは1216年に新たにアッコ司教に任じられ、その後まもなくホノリウスよりシリア地方での布教・説教活動に従事するよう命じられたが、当地域の港町が制御不能なほど腐敗していたためその任務は困難を極めた[16]。

フランスでの説教活動が不発に終わった一方、Oliver of Paderbornが行ったドイツでの活動では大成功を収めた[17]。1216年、ホノリウス3世はハンガリー王アンドラーシュ2世に対して、父王の立てた誓いを果たすよう十字軍への参加を呼び掛けた。またその他の諸侯たちと同様に、かつて教皇インノケンティウス3世の後見を受けていた神聖ローマ皇帝フリードリヒ2世は1215年に十字軍参加の誓いを立てており、配下の諸侯に対しても参加するよう呼び掛けていた。しかしフリードリヒ2世は帝位を巡るオットー4世との対立が続いていることからヨーロッパをなかなか離れられなかったため、ホノリウス3世はたびたび遠征を延期する決定を下したという。

ヨーロッパではトルバドゥールたちも十字軍への関心を呼び覚ますのに一役買った。第4回十字軍参加経験のあるElias Cairelや、のちに1220年の遠征することとなるPons de Capduelh、自身の詩作で若きグリエルモ6世(ボニファーチョ1世の息子)に対して父親の足跡をたどり十字軍に参加するよう説得したことで知られるAimery de Pégulhanといった詩人たちがその面々である。

最終的に、十字軍の参加兵力は1万人以上の騎士を含めて3万2千を超える規模になったと推定されている。当時のアラブ人歴史家は、「この年、無数の戦士が偉大な都市ローマやその他の西方の国々を発った。」と説明している[18]。十字軍は戦士のみならず、カウンターウェイト式トレビュシェットを含む当時最新鋭とされていた攻城兵器の数々をも有していた[19]。

イベリア半島並びにレヴァント

[編集]1217年7月初頭、遂に十字軍の諸部隊が出陣を開始した。多くの十字軍戦士は伝統的な遠征ルートである地中海横断ルートを採った[20]。十字軍艦隊はまず初めにイングランド南部の港町ダートマス(Dartmouth)に寄港した。この地で十字軍は自分たちの艦隊の総司令官を選出し、航海中のルールを取り決めた。結果、ホラント伯ウィレム1世が総司令官に選出され、ダートマス出航後はウィレム伯の指揮下で航行し、リスボンを目指して南下を開始した。しかしこの艦隊は途中で嵐に遭遇し散り散りになり、各々の艦船はサンティアゴ・デ・コンポステーラの著名な寺院に立ち寄りつつポルトガルの都市リスボンに再集結した[21]。

ポルトガル到着後、リスボン司教は十字軍たちにムワッヒド朝の支配を受けていたアルカセル・ド・サルの奪還を支援するよう説得を試みた。しかし十字軍艦隊の一翼を成すフリース人部隊は、ポルトガルへの支援が第4ラテラノ公会議での取り決めの反し教皇による処分の対象になるとして司教の要請を拒否し、その他の部隊のみポルトガルを支援した。フリース人を除いた十字軍部隊はポルトガル軍と共に1217年8月、アルカセル・ド・サルに対する包囲攻撃を敢行した。そして1217年10月、十字軍はテンプル騎士団・ホスピタル騎士団の助力を得てアルカセル・ド・サルを攻め落とした[22]。

ポルトガル軍への支援を拒んだフリース人部隊は、聖地までの道中に沿岸諸都市の略奪を繰り返しながら進軍し続けた。彼らはFaro、Rota、Cádiz、そしてIbizaといった諸都市を攻めながら進み、略奪を通じて多くの戦利品を獲得した。その後彼らは南フランス沿岸に沿って航行し、1217年末から1218年初にかけての冬をイタリアのCivitavecchiaで過ごした[23]。一方この頃、北ヨーロッパではノルウェー王インゲ2世が1216年に十字軍の誓いを立たのであるが、翌春に死去し、最終的に行われたスカンジナビアの遠征はほとんど重要な結果をもたらさなかった[24]。

教皇インノケンティウス3世は東方のキリスト教国であるジョージア王国をも十字軍遠征に参加させようと試みた[25]。当時のジョージア女王タマルはジョージア王国の最盛期を築き上げており、その勢いはアナトリア半島東部におけるアイユーブ朝の派遣に挑戦を仕掛けるほどであった。1213年に女王が崩御したのち、タマルの息子ギオルギ4世 (グルジア王)が王位を継承した。ジョージア年代記によれば、1210年代後半ごろにギオルギ王はフランク人の聖地遠征に対する支援を決めており、遠征準備を行っていたとされるが、1220年に開始されたモンゴル帝国によるジョージア遠征により十字軍への参加を取りやめざるを得ない状況に追い込まれたという。ギオルギ4世の死後、彼の妹であるルスダンは教皇に対してジョージアの十字軍参加が困難であることを伝え、誓いを果たせないと通告した[26]。

聖地の状況

[編集]1193年、サラディンが亡くなり彼の支配地域の大半は彼の弟アル・アーディルが継承し、最終的にはアイユーブ朝スルタンの座を継承した。またサラディンの3男:ザーヒル・ガーズィーはアレッポを中心とする領地の統治を確実なものとした。ナイル川下流域では、1201年から1202年にかけて記録的な不作に見舞われ、飢饉や疫病の蔓延が当地域を襲った。結果的にこの地域の住民はおぞましい行為に身を投じることとなり、足りない食料を習慣的にカニバリズムを通して補うようになった。また、この地域ではシリアやアルメニア地域にまで及ぶ激しい地震が襲ったとされ、状況をさらに悪化させることとなった[27]。

1204年のロゼッタ襲撃事件や1211年のダミエッタ襲撃事件などを目の当たりにしたアーディルは、アイユーブ朝支配地域の中でも特にエジプト地域について頭を悩ませることとなった。彼は十字軍との戦役を避けるために譲歩も辞さぬ考えを示し、ヴェネツィア共和国並びにピサ共和国との交易協定を締結することで、交易を続けるとともに両共和国の来たる十字軍への参加や支援を困難にさせた。彼の治世の大半の時期は十字軍と講和状態にあり、またタボル山に新しい砦を築きエルサレムとダマスカスの防衛の要とした。彼の治世においてシリア地域で勃発していた紛争の多くはクラック・デ・シュヴァリエに拠点を置くホスピタル騎士団並びにアンティオキア公ボエモン4世との対立によるものであり、それらはアーディルの甥ザーヒルによって対処された。1207年、彼は一度だけ直接十字軍と対峙することがあり、この際はアーディルはal-Qualai'ah(現在のレバノン北部に存在した砦)を攻め落とし、続けてクラック・デ・シュヴァリエを包囲し、その上トリポリの向けて北進を敢行した。結局この紛争はボエモン4世から賠償金を得ることで終結した[28]。

ザーヒルはアンティオキア公やルーム・セルジューク朝のスルタンカイカーウス1世と同盟を締結し、アルメニア王レヴォン1世の影響力の増大を抑えた。また、彼の叔父でアイユーブ朝の指導者であるアーディルへの挑戦という選択肢も温存していた。しかしザーヒルは1216年に、まだ3歳の幼い息子アル=アーズィズ・ムハンマド(母親はアーディルの娘のen:Dayfa Khatun)を残してこの世を去った。ザーヒルの死後、サラディンの長男:アル=アフダルはカイカーウス1世の支援を得てアレッポへの侵攻を試み始めた。そして1218年、セルジューク朝の援軍と共にアフダルはアレッポに侵攻を開始し首都に向けて進軍した。しかしこの侵攻はダマスカスのエミール:アル=アシュラフ・ムーサーの活躍により失敗に終わり、アシュラフの攻撃を受けて弱体化したルーム・セルジューク朝に対して、カイカーウス1世が1220年に亡くなるまでアシュラフは脅威であり続けた。以上のようにアイユーブ朝のレヴァント支配は不安定なものであったため、アイユーブ朝は各地に兵力を派遣する必要があり、それはエジプトを攻略目標としていた十字軍にとって好都合であった[29]。

ハンガリー王アンドラーシュ2世の十字軍

[編集]第5回十字軍において最初に誓いを立てたヨーロッパ諸侯はハンガリー王アンドラーシュ2世であった[30]。アンドラーシュ2世は1216年7月にローマ教皇から父王ベーラ3世が立てた十字軍の誓いを果たすよう呼びかけをうけ、3度の延期を経て最終的に十字軍遠征を行った。アンドラーシュ2世は当時ラテン皇帝への就任を目論んでいたと噂されており、王国領を抵当に入れて十字軍の遠征費用を賄った[31]。1217年7月、アンドラーシュ2世率いるハンガリー軍はオーストリア公レオポルト6世・メラニア公オットー1世と共にザグレブを出立した[32][33]。アンドラーシュ王の軍団は非常に大規模なものであり、2万の騎馬隊と数えきれないほどの歩兵から成っていた。しかしこの軍団の多くは本体とは別に進軍したとされ、アンドラーシュ王が出発してから2か月ほどのちにスプリトから出陣した[32][34]。彼らは当時最大規模の艦隊とされていたヴェネツィア共和国艦隊によって輸送された[35]。アンドラーシュ王率いるハンガリー軍は1217年8月23日にスプリトから出港した。

ハンガリー軍は1217年10月9日にキプロス島に上陸し、そこから再びアッコに向けて航海を続け、ジャン・ド・ブリエンヌ、エルサレム大司教ラウール、キプロス王ユーグ1世らと合流した。アンドラーシュ王はハンガリーに帰還するまでの間、第5回十字軍の総大将として聖地に滞在し続けた[36]。1217年10月、十字軍諸侯らはアンドラーシュ王主催の軍議を開催した。この会議にはホスピタル騎士団総長ゲラン・ド・モンタギュー、テンプル騎士団総長ギヨーム・ド・シャルトル、チュートン騎士団総長ヘルマン・フォン・ザルツァといった騎士修道会の代表者や[37]、オーストリア公レオポルト6世、メラニア公オットー1世、ゴーティエ2世・ダヴェーヌといった諸侯や多くの大司教・司教が参加した[38]。

ジャン・ド・ブリエンヌは2方面作戦を計画していた。シリア地域では、アンドラーシュ王率いる軍団がアル=アーディルの息子アル=ムアッザム・イーサーとナーブルスの砦で対峙し、同時に十字軍艦隊が海上からエジプトを攻撃しエジプトからムスリム軍を一掃し、その地を拠点にシリアやパレスチナ地域を順次征服するという計画であった。しかしこの計画は人手不足並びに軍船不足により放棄された。代わりに、十字軍はヨーロッパからのさらなる援軍を見越して、ムスリム軍を小規模な紛争に引き込み小競り合いを繰り返し、必要であればダマスカスへの進軍も視野に入れるという作戦が採用された[39]。

1216年、アレクサンドリアから大勢の商人が脱出したことを受けてムスリムは十字軍の遠征が近いことを察した。そしてアッコに十字軍が集結すると、アル=アーディルは長男でかつ総督であったアル=カーミルに自軍の大半を与えた上でエジプトを任せ、自身はシリアでの軍事活動に専念した。アーディルは個人的な小規模な部隊を率いて、ダマスカス統治者アル=ムアッザムの支援を行った。しかし彼の手持ちの軍勢だけでは十字軍に到底対抗できなかったため、彼自身はダマスカスへ通じる道を防衛し、ムアッザムをナーブルスに派遣しエルサレムを防衛させた[28]。

一方に十字軍はアッコ付近のテル・アフェクに駐屯し、1217年11月3日にエズレル平野を横断してアイン・ジャールートに進軍した。十字軍はこの地でムスリム軍の奇襲を予想していたが、アル=アーディルは十字軍の精強さを目の当たりにし、ナインの丘陵地から十字軍に奇襲を仕掛けるべきだと強く主張するムアッザムの反対を押し切って、ベト・シェアンに向けて撤退した。そして今度は息子の反対を押し切って、アル=アーディルはベト・シェアンの街も放棄し、その街はその後すぐ十字軍に蹂躙され略奪を受けた。アーディルはアジュルンまで撤退を続け、ムアッザムに対してシロ市街付近のルッバンの丘陵地に陣を置きエルサレムを防衛するよう命じた。アーディル自身はダマスカスにむけてそのまま軍をすすめ、ダマスカス南部のマルジュ・アル=サッファール平野に陣を敷いた[40]。

1217年11月、十字軍はジスル・エル・マジャミー橋を通ってヨルダン川を渡河してダマスカスを脅かした。ダマスカスの統治者は防衛態勢を整え、またアイユーブ朝のホムズ総督al-Mujahid Shirkuhからの援軍を得て対抗した。十字軍は一戦も交えることなくアッコ近郊の陣に撤退した。その後というもの、アンドラーシュ王は戦場に戻ることなく聖遺物探しに専念した[41]。

その後、ハンガリー軍はボエモン3世に支援されたジャン・ド・ブリエンヌの指揮下に入り、タボル山に向けて進軍したが、ムスリム軍は山で鉄壁の守りを固めていた。1217年12月3日、十字軍はタボル山に攻めかかったがその後まもなく撤退した。その後、テンプル騎士団並びにホスピタル騎士団が再び攻め込んだが、ギリシャ火薬の攻撃を受け同年12月7日に再び撤退に追い込まれた[42]。その後、3度目の攻撃がハンガリー軍(アンドラーシュ王の甥が率いていたともされている。)によって行われたが、この攻撃はMashgharaで壊滅的な被害を被って幕を閉じた。攻め寄せたハンガリー軍は多くが殺害され、わずかな生存者はクリスマスイブにアッコに逃げ帰った。加えて、この大敗によってハンガリー軍は十字軍遠征から身を引いたのであった[43]。

1218年初頭、病弱なアンドラーシュ王は教皇による破門宣告の危険を冒しつつも母国ハンガリーに帰国することを決め[35]、同年2月にハンガリーに向けて旅立った。道中、アンドラーシュ王はボエモン3世とMelisende of Lusignanとの結婚式に参列すべくトリポリに立ち寄った。アンドラーシュ王らと共に参列していたキプロス王ユーグ1世はこの式典の最中に病に倒れ、その後まもなく亡くなった。その後、アンドラーシュ王は同年後半に聖地を後にして母国に帰還した[44]。

一方そのころ、聖地ではテンプル騎士団やゴーティエ2世・ド・アヴェーヌの支援の下でペレリン城の防衛力強化を進め、このカイサリア地域の防衛強化政策はのちに大いに役に立ったという。また同年後半、ヨーロッパから新たな援軍が到来した。ドイツ人聖職者オリヴァー・ヴォン・パーダーボルン率いるドイツ人軍団やホラント伯ウィレム1世率いるオランダ人・フラマン人・フリース人たちから成る混成軍団である。また、神聖ローマ皇帝フリードリヒ2世の不参加が明らかになるや否や、彼らは十字軍遠征の具体的な計画の立案を開始した。この遠征は王国における彼の聖地における立場と軍事的名声から鑑みて、ジャン・ド・ブリエンヌが総指揮を執ることとなった。かつて廃案となったエジプト攻撃案は、人員などの不足が解消されたことを機に再び考慮されることとなり、最終的にはエジプトへの侵攻が取り決められた。しかしエルサレムへの春季攻撃作戦案は猛暑並びに水不足により却下された。また、エジプト攻撃作戦においてはアレクサンドリア市街ではなくダミエッタ港が攻略目標として定められた。十字軍はエルサレム王国や騎士修道会からの軍事的援助も得てこの作戦を執り行うこととなった[45]。

The campaign in Egypt

[編集]On 27 May 1218, the first of the Crusader's fleet arrived at the harbor of Damietta, on the right bank of the Nile.[46] Simon III of Sarrebrück was chosen as temporary leader pending the arrival of the rest of the fleet. Within a few days, the remaining ships arrived, carrying John of Brienne, Leopold VI of Austria and masters Peire de Montagut, Hermann of Salza and Guérin de Montaigu. A lunar eclipse on 9 July was viewed as a good omen.[47]

The Muslims were not alarmed at the arrival of the Crusaders, believing that they would not successfully mount an attack on Egypt. Al-Adil was both surprised and disappointed in the West, supporting peace treaties when more radical elements in the sultanate sought jihad. He was still camped at Marj al-Saffar, and his sons al-Kamil and al-Mu'azzam were tasked with defending Cairo and the Syrian coast, respectively. Available reinforcements were sent from Syria, and an Egyptian force encamped at al-'Adiliyah, a few miles south of Damietta. The Egyptians were of insufficient strength to attack the Crusaders, but did serve to oppose any invader attempt to cross the Nile.[48]

The Tower of Damietta

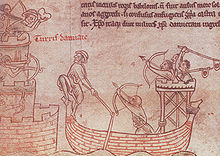

[編集]The fortifications of Damietta were impressive, consisting of three walls of varying heights, with dozens of towers on the interior, and were enhanced to repel the invaders. Situated on an island in the Nile was the Burj al-Silsilah—the chain tower—called so because of the massive iron chains that could stretch across the river preventing passage. The tower, containing 70 tiers and housing hundreds of soldiers, was key to the capture of the city.[49]

The siege of Damietta began on 23 June 1218 with an assault on the tower, utilizing upwards of 80 ships some with projectile machines, with no success. Two new types of vessels were adapted to meet the needs of the siege. The first, used by Leopold VI and the Hospitallers, was able to secure scaling ladders mounted on two ships bound together. The second, called a maremme, was commanded by Adolf VI of Berg and included a small fortress on the mast to hurl stones and javelins. The maremme, attacking first, was forced to withdraw when faced with an intense counter-barrage. The scaling ladders, secured against the walls, collapsed under the weight of the soldiers. The first attempt at an assault was a failure.[50][51]

Oliver of Paderborn, supported by his Frisian and German followers, demonstrating considerable ingenuity and leadership, constructed an ingenious siege engine combining the best features of the earlier models. Protected from Greek fire by hides, it included a revolving ladder that extended far beyond the ship.[52] On 24 August the renewed assault began. By the next day, the tower was taken and the defensive chains cut.[53]

The loss of the tower was a great shock to the Ayyubids, and the sultan al-Adil died shortly thereafter, on 31 August 1218. His body was secretly taken to Damascus and his treasure dispersed before his death was announced. He was succeeded as sultan by his son al-Kamil. The new sultan immediately implemented defensive measures, including scuttling a number of ships a mile upstream, resulting in the Nile being blocked for much of the winter of 1218–1219.[54]

Preparation for the siege

[編集]The Crusaders did not press their advantage, and many prepared to return home, regarding their crusading vows satisfied. Further offensive action would nevertheless have to wait until the Nile was more favourable and the arrival of additional forces. Among them were papal legate Pelagius Galvani and his aide Robert of Courçon, who travelled with a contingent of Roman Crusaders financed by the pope. A group from England, smaller than expected arrived shortly, led by Ranulf de Blondeville, and Oliver and Richard, illegitimate sons of King John.[55] A group of French Crusaders that arrived at the end of October included Guillaume II de Genève, archbishop of Bordeaux, and the newly elected bishop of Beauvais, Milo of Nanteuil.[53]

On 9 October 1218, Egyptian forces conducted a surprise attack on the Crusaders' camp. Discovering their movements, John of Brienne and his retinue attacked and annihilated the Egyptian advance guard, hindering the main force. From the outset, Pelagius considered himself the supreme commander of the Crusade, and, unable to mount a major offensive, sent specially equipped ships up the Nile to no avail. A follow-on attack on the Crusaders on 26 October also failed, as did a Crusader attempt to dredge an abandoned canal, the al-Azraq, to bypass al-Kamil's new defensive measures on the Nile.[56]

The Crusaders now built an enormous floating fortress on the river, but a storm that began on 9 November 1218 blew it near the Egyptian camp. The Egyptians seized the fortress, killing nearly all of its defenders. Only two soldiers survived the attack. They were accused of cowardice, and John ordered their execution. The storm, lasting 3 days, flooded both camps and the Crusaders' supplies and transportation were devastated. In the ensuing months diseases killed many of the Crusaders, including Robert of Courçon.[57] During the storm, Pelagius took control of the expedition. The Crusaders supported this, feeling the need for new, more aggressive leadership. By February 1219, they were able to mount new offensives, but were unsuccessful because of the weather and strength of the defenders.

At this time, al-Kamil, in command of the defenders, when he was almost overthrown by a coup to replace him with his younger brother al-Faiz Ibrahim.[58] Alerted to the conspiracy, al-Kamil had to flee the camp to safety and in the ensuing confusion the Crusaders were able to advance on Damietta. Al-Kamil considered fleeing to the Ayyubid emirate of Yemen, ruled by his son al-Mas'ud Yusuf, but the arrival of his brother al-Mu'azzam with reinforcements from Syria ended the conspiracy. The Crusader attack mounted against the Egyptians on 5 February 1219 was then different, the defenders having fled, abandoning the camp.[59]

The Crusaders now surrounded Damietta, with the Italians to the north, Templars and Hospitallers to the east, and John of Brienne with his French and Pisan troops to the south. The Frisians and Germans occupied the old camp across the river. A new wave of reinforcements from Cyprus arrived led by Walter III of Caesarea.

At this point, al-Kamil and al-Mu'azzam attempted to open negotiations with the Crusaders, asking Christian envoys to come to their camp. They offered to surrender the kingdom of Jerusalem, less al-Karak and Krak de Montréal which guarded to road to Egypt, with a multi-year truce, in exchange for the Crusaders' evacuation of Egypt. John of Brienne and the other secular leaders were in favour of the offer, as the original objective of the Crusade was the recovery of Jerusalem. But Pelagius and the leaders of the Templars, Hospitallers and Venetians refused this and a subsequent offer with compensation for the fortresses, damaging the unity of the enterprise. Al-Mu'azzam responded by reorganizing his reinforcements at Fariskur, upriver from al-'Adiliyah. Unknown to the Crusaders, Damietta could have been easily taken at this point due to illness and death among the defenders.

In the Holy Land, al-Mu'azzam's forces began dismantling fortifications at Mount Tabor and other defensive positions, as well as Jerusalem itself, in order to deny their protection should the Crusaders prevail there. Al-Muzaffar II Mahmud, the son of the Ayyubid emir of Hama (and later emir himself), arrived in Egypt with Syrian reinforcements, leading multiple attacks on the Crusader camp through 7 April 1219, with little impact. In the meantime, Crusaders such as Leopold VI of Austria were returning to Europe, but were more than offset by new recruits, including Guy I Embriaco, who brought badly-needed supplies.[60] Muslim attacks continued through May, with Crusader counterattacks utilizing a Lombardy device known as a carroccio, confounding the defenders.[61]

Despite objections from the military leaders, Pelagius began multiple attacks on the city on 8 July 1219 using Pisan and Venetian troops. Each time they were repelled by the defenders, using Greek fire. A counteroffensive by the Egyptians on the Templar camp on 31 July was repulsed by their new leader Peire de Montagut, supported by the Teutonic Knights. Fighting continued into August when the waters of the Nile receded. An attack on the sultan's camp at Fariskur on 29 August led by Pelagius' faction was a disaster, resulting in high losses for the Crusaders. The Marshal of the Hospitaller, Aymar de Lairon, and many Templars were killed. Only the intervention by John of Brienne, Ranulf de Blondeville, and the Templars and Hospitallers prevented further loss.[62]

In August 1219, the sultan again offered peace, possibly out of desperation, using recent captives as envoys to the Christians. This included his earlier provisions plus paying for the restoration of the damaged fortifications, the return of the portion of the True Cross lost at the battle of Hattin and the release of prisoners. Again, his offer was rejected along familiar lines. Pelagius' view that victory was possible was supported by the continued arrival of new Crusades, most notably an English force led by Savari de Mauléon, a seneschal of the late John of England.[63]

Saint Francis in Egypt

[編集]

In September 1219, Francis of Assisi arrived in the Crusader camp seeking permission from Pelagius to visit sultan al-Kamil.[64] Francis had a long history with the Crusades.[65] In 1205, Francis prepared to enlist in the army of Walter III of Brienne (brother of John), diverted from the Fourth Crusade to fight in Italy. He returned to a life of the mendicants, later meeting with Innocent III who approved his religious order. After the Christian victory at the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212, he travelled to meet with Almohad caliph Muhammad an-Nāsir, ostensibly to convert him to Christianity. Francis did not make it to Morocco, only getting as far as Santiago de Compostela, he returned, sickened, but with a mission. His fabled experience with the wolf of Gubbio exemplified his view of the power of the cross.[66]

Initially refusing the request, Pelagius granted Francis and his companion, Illuminato da Rieti, to go on what was assumed to be a suicide mission.[67] They crossed over to preach to al-Kamil, who assumed that the holy men were emissaries of the Crusaders and received them courteously. When he discovered that their intent was instead to preach against the evils of Islam, some in his court demanded the execution of the friars. Al-Kamil instead heard them out and had them escorted back to the Crusader camp.[68] Francis did obtain a commitment for more humane treatment for the Christian captives. It was claimed in a sermon by Bonaventure that the sultan converted or accepted a death-bed baptism as a result of his meeting with Francis.[69]

Francis remained in Egypt through the fall of Damietta, departing then for Acre. While there, he established the Province of the Holy Land, a priory of the Franciscan Order, obtaining for the friars the foothold they still retain as guardians of the holy places.[70]

The Siege of Damietta

[編集]With the negotiations with the Crusaders stalled and Damietta isolated, on 3 November 1219 al-Kamil sent a resupply convoy through the sector manned by the troops of the Frenchman Hervé IV of Donzy. The Egyptians were by and large stopped, some getting through to the city, resulting in the expulsion of Hervé. The intrusion energized the Crusaders with a unity of purpose.[71]

On 5 November 1219, suspecting the city had been vacated, the Crusaders entered Damietta and found it abandoned, filled with the dead and with most of the remaining citizens ill. Seeing the Christian banners flying over the city, al-Kamil moved his host from Fariskur downriver to Mansurah. Survivors in the city were either sent into slavery or held as hostage to trade for Christian prisoners.[72]

The fortifications of Damietta were essentially undamaged, and the victorious Crusaders claimed much booty. By 23 November 1219, they had captured the neighboring city of Tinnis, on the Tanitic mouth of the Nile, providing access to the food sources of Lake Manzala.[73]

As usual, there was partisan struggles as to the rule of the city, secular or ecclesiastic. At some point, John of Brienne had enough, equipping three ships for departure. Pelagius relented, allowing John to lead Damietta pending a decision by the pope. Nevertheless, the Italians, feeling deprived of booty, took arms against the French and expelled them from the city. Not until 2 February 1220 did the situation stabilize, with a formal ceremony conducted to celebrate the Christian victory. John soon departed for the Holy Land, either piqued at Pelagius or to stake his claim to Armenia. Either way, Honorius III soon decided Damietta's fate in favour of his legate Pelagius.[74]

Among the casualties of the campaign for Damietta were Oliver, son of John Lackland, Milo IV of Puiset and his son Walter, and Hugh IX of Lusignan. Templar Guillaume de Chartres died of the plague before the siege began.[75]

John of Brienne returns to Jerusalem

[編集]The father-in-law of John of Brienne, Leo I of Armenia, died on 2 May 1219, leaving his succession in doubt. John's claim to the Armenian throne was through his wife Stephanie of Armenia and their infant son, and Leo I had instead left the kingdom to his infant daughter Isabella of Armenia. The pope decreed in February 1220 that John was the rightful heir to the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. John left Damietta for Jerusalem around Easter 1220 in order to assert his claim to his inheritance. His departure had been rumored to be due to desertion which was not the case.[76]

Stephanie and their son died shortly after John's arrival, ending his claim to Cilicia. When Honorius III learned of their deaths, he declared Raymond-Roupen (whom Leo I had disinherited) the lawful ruler, threatening John with excommunication if he fought for Cilicia. To solidify his position, Raymond-Roupen travelled to Damietta in the summer of 1220 to meet with Pelagius.[77]

After Damietta was captured, Walter of Caesarea had brought 100 Cypriote knights and their men-at-arms, including a Cypriote knight named Peter Chappe, and his charge, a young Philip of Novara. While in Egypt, Philip received instruction from the jurisconsult Ralph of Tiberias. In John's absence, Pelagius left the sea routes between Damietta and Acre unguarded, and a Muslim fleet attacked the Crusaders in the port of Limassol, resulting in over a thousand casualties. Most of the Cypriotes departed Egypt at the same time as John. When he returned, he passed through Cyprus and brought some forces with him.[78]

John remained in Jerusalem for several months, primarily due to lack of funds. Since his nephew Walter IV of Brienne was approaching the age of majority, John surrendered the County of Brienne to him in 1221. John returned to Egypt and rejoined the Crusade on 6 July 1221 at the direction of the pope.[79]

Disaster at Mansurah

[編集]The situation in Damietta after the February 1220 celebration was one of inactivity and discontent. The army lacked discipline despite Pelagius' draconian rule. His extensive regulations prevented adequate protection of the shipping lanes from Cyprus, and several ships carrying pilgrims were sunk. Many Crusaders departed, but were supplement by fresh troops including contingents led by the archbishop of Milan, Enrico da Settala, and the unnamed archbishop of Crete. This was the prelude to the disastrous battle of Mansurah of 1221 that would end the Crusade.[80]

Late in 1220 or early in 1221, al-Kamil sent Fakhr ad-Din ibn as-Shaikh on an embassy to the court of al-Kamil's brother al-Ashraf, now ruling greater Armenia from Sinjar, to request assistance against the Crusaders. He was at first refused.[81] The Muslim world was now threatened also by the Mongols in Persia. When Abbasid caliph al-Nasir requested troops from al-Ashraf, however, the latter chose instead to send them assist his brother in Egypt. The Ayyubids regarded the Mongol ouster of Ala ad-Din Muhammad II, shah of the Khwarazmians, as destroying one of their main enemies, allowing them to focus on the invaders at Damietta.[82]

In the captured city, Pelagius was unable to prod the Crusaders from their inactivity through the year 1220, save for a Templar raiding party on Burlus in July 1220. The town was pillaged, but at the cost of the loss and capture of numerous knights. The relative calm in Egypt enabled al-Mu'azzam, returning to Syria after the defeat at Damietta, to attack the remaining coastal strongholds, taking Caesarea. By October, he had further degraded the defenses of Jerusalem and unsuccessfully attacking Château Pèlerin, defended by Peire de Montagut and his Templars, recently released from their duty in Egypt.[83]

Al-Kamil took advantage of this lull to reinforce Mansurah, once a small camp, into a fortified city that could perhaps replace Damietta as the protector of the mouth of the Nile.[84] At some point, he renewed his peace offering to the Crusaders. Again it was refused, with Pelagius' view that he held the key to conquering not only Egypt but also Jerusalem. In December 1220, Honorius III announced that Frederick II would soon be sending troops, expected now in March 1221, with the newly crowned emperor leaving for Egypt in August. Some troops did arrive in May, led by Louis I of Bavaria and his bishop, Ulrich II of Passau, and under orders not to begin offensive operations until Frederick arrived.[83]

Even before the capture of Damietta, the Crusaders became aware of a book, written in Arabic, which claims to have predicted Saladin's earlier capture of Jerusalem and the impending Christian capture of Damietta.[85] Based on this and other prophetic works, rumors circulated of a Christian uprising against the power of Islam, influencing the consideration of al-Kamil's peace offerings. Then in July 1221, rumors began that the army of one King David,[86] a descendant of the legendary Prester John, was on its way from the east to the Holy Land to join the Crusade and gain release of the sultan's Christian captives. The story soon grew to such proportions and generated so much excitement among the Crusaders that it led them to prematurely launch an attack on Cairo.[87] In reality, these rumors were conflated with the reality of Genghis Khan and the Mongol invasions of Persia.[88]

On 4 July 1221 Pelagius, having decided to advance to the south, ordered a three-day fast in preparation for the advance. John of Brienne, arriving in Egypt shortly thereafter, argued against the move, but was powerless to stop it. Already deemed a traitor for opposing the plans and threatened with excommunication, John joined the force under the command of the legate. They moved towards Fariskur on 12 July where Pelagius drew it up in battle formation.[89]

The Crusader force advanced to Sharamsah, half-way between Fariskur and Mansurah on the east bank of the Nile, occupying the city on 12 July 1221. John of Brienne again attempted to turn the legate back, but the Crusader force was intent on gaining great booty from Cairo, and John would likely have been put to death if he persisted. On 24 July, Pelagius moved his forces near the al-Bahr as-Saghit (Ushmum canal), south of the village of Ashmun al-Rumman, on the opposite bank from Mansurah. His plan was to maintain supply lines with Damietta, not bringing sufficient food for his large army.

The fortifications established were less than ideal, made worse by the reinforcements the Egyptians brought in from Syria. Alice of Cyprus and the leaders of the military orders warned Pelagius of the large numbers of Muslims troops arriving and continued warnings from John of Brienne went unheeded. Many Crusaders took this opportunity to retreat back to Damietta, later departing for home.

The Egyptians had the advantage of knowing the terrain, especially the canals near the Crusader camp. One such canal near Barāmūn (see maps of the area here[46] and here[90]) could support large vessels in late August when the Nile was at its crest, and they brought numerous ships up from al-Maḥallah. Entering the Nile, they were able to block the Crusaders' line of communications to Damietta, rendering their position untenable. In consultation with his military leaders, Pelagius ordered a retreat, only to find the route to Damietta blocked by the sultan's troops.[91]

On 26 August 1221, the Crusaders attempted to reach Barāmūn under the cover of darkness, but their carelessness alerted the Egyptians who set on them. They were also reluctant to sacrifice their stores of wine, drinking them rather than leave them. In the meantime, al-Kamil had the sluices along the right bank of the Nile opened, flooding the area and rendering battle impossible. On 28 August, Pelagius sued for peace, sending an envoy to al-Kamil.[92]

The Crusaders still had some leverage. Damietta was well-garrisoned and a naval squadron under fleet admiral Henry of Malta, and Sicilian chancellor Walter of Palearia and German imperial marshal Anselm of Justingen, had been sent by Frederick II. They offered the sultan withdrawal from Damietta and an eight-year truce in exchange for allowing the Crusader army to pass, the release of all prisoners, and the return of the relic of the True Cross. Prior to the formal surrender of Damietta, the two sides would maintain hostages, among them John of Brienne and Hermann of Salza for the Franks side and as-Salih Ayyub, son of al-Kamil, for Egypt.[93]

The masters of the military orders were dispatched to Damietta with the news of the surrender. It was not well-received, with the Venetians attempting to gain control, but the eventual happened on 8 September 1221. The Crusader ships departed and the sultan entered the city. The Fifth Crusade was over.[94]

Aftermath

[編集]The Fifth Crusade ended with nothing gained for the West, with much loss of life, resources and reputations. Most were bitter that offensive operations were begun prior to the arrival of the emperor's forces, and had opposed the treaty. Walter of Palearia was stripped of his possessions and sent into exile. Admiral Henry of Malta was imprisoned only to be pardoned later by Frederick II. John of Brienne demonstrated his inability to command an international army and was censured for essentially deserting the Crusade in 1220. Pelagius was accused of ineffectual leadership and a misguided view that led him to reject the sultan's peace offering.[95] The greatest criticism was leveled at Frederick II, whose ambition clearly lay in Europe not the Holy Land. The Crusade was unable to even gain the return of the piece of the True Cross. The Egyptians could not find it and the Crusaders left empty-handed.[96]

The failure of the Crusade caused an outpouring of anti-papal sentiment from the Occitan poet Guilhem Figueira. The more orthodox Gormonda de Monpeslier responded to Figueira's D'un sirventes far with a song of her own, Greu m'es a durar. Instead of blaming Pelagius or the Papacy, she laid the blame on the "foolishness" of the wicked. The Palästinalied is a famous lyric poem by Walther von der Vogelweide written in Middle High German describing a pilgrim travelling to the Holy Land during the height of the Fifth Crusade.[97][より良い情報源が必要]

Participants

[編集]A partial list of those that participated in the Fifth Crusade can be found in the category collections of Christians of the Fifth Crusade and Muslims of the Fifth Crusade.

Historiography

[編集]The historiography of the Fifth Crusade is concerned with the "history of the histories" of the military campaigns discussed herein as well as biographies of the important figures of the period. The primary sources include works written in the medieval period, generally by participants in the Crusade or written contemporaneously with the event. The secondary sources begin with early consolidated works in the 16th century and continuing to modern times. The tertiary sources are primarily encyclopedias, bibliographies and biographies/genealogies.[98]

The primary Western sources of the Fifth Crusade were first complied in Gesta Dei per Francos (God's Work through the Franks) (1611), by French scholar and diplomat Jacques Bongars.[99] These include several eyewitness accounts, and are as follows.

- Estoire d’Eracles émperor (History of Heraclius) is an anonymous history of Jerusalem down to 1277, a continuation of William of Tyre's work and drawing from both Ernoul and the Rothelin Continuation.[100]

- Historia Orientalis (Historia Hierosolymitana) and Epistolae, by theologian and historian Jacques de Vitry.[101]

- Historia Damiatina, by Cardinal Oliver of Paderborn (Oliverus scholasticus) reflects his experience in the Crusade.[102]

- De Itinere Frisonum is an eyewitness account of the Frisians' journey from Friesland to Acre.[103]

- Flores Historiarum, by English chronicler Roger of Wendover,[104] covering the period from 1188 through the Fifth Crusade.[105]

- Gesta crucigerorum Rhenanorum, an account of the Rhineland Crusaders in 1220.[106]

- Gesta Innocentii III, written by a member of the pope's curia.[107]

- Chronicon, by Richard of San Germano.[108]

Other primary sources include:

- De expugnatione Salaciae carmen by Goswin of Bossut[109]

- Gesta obsidionis Damiate by Giovanni Codagnello[110]

The Arabic sources of the Crusade, partially compiled in the collection Recueil des historiens des croisades, Historiens orientaux (1872–1906), include the following.

- Complete Work of History, particularly The Years 589–629/1193–1231, by Ali ibn al-Athir, an Arab or Kurdish historian.[111]

- Kitāb al-rawḍatayn (The Book of the Two Gardens) and its sequel al-Dhayl ʿalā l-rawḍatayn, by Arab historian Abū Shāma.[112]

- Tarikh al-Mukhtasar fi Akhbar al-Bashar (History of Abu al-Fida), by Kurdish historian Abu’l-Fida.[113]

- History of Egypt, by Egyptian historian Al-Makrizi.[114]

- History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria, begun in the 10th century, and continued into the 13th century.

Many of these primary sources can be found in Crusade Texts in Translation. Fifteenth century Italian chronicler Francesco Amadi wrote his Chroniques d'Amadi that includes the Fifth Crusade based on the original sources.[115] German historian Reinhold Röhricht also compiled two collections of works concerning the Fifth Crusade: Scriptores Minores Quinti Belli sacri (1879)[116] and its continuation Testimonia minora de quinto bello sacro (1882).[117] He also collaborated on the work Annales de Terre Sainte that provides a chronology of the Crusade correlated with the original sources.[118]

The reference to the Fifth Crusade is relatively new. Thomas Fuller[119] called it simply Voyage 8 in his The Historie of the Holy Warre.[120] Joseph-François Michaud[121] referred to it as part of the Sixth Crusade in his Histoire des Croisades (translation by British author William Robson),[3] as did Joseph Toussaint Reinaud[122] in his Histoire de la sixième croisade et de la prise de Damiette.[123] Historian George Cox[124] in his The Crusades regarded the Fifth and Sixth Crusades as a single campaign,[125] but by the late 19th century, the designation of the Fifth Crusade was standard.

The secondary sources are well-represented in the Bibliography, below. Tertiary sources include works by Louis Bréhier in the Catholic Encyclopedia,[126] Ernest Barker in the Encyclopædia Britannica,[127] and Philip Schaff in the Schaff-Herzog Encyclopaedia of Religious Knowledge.[128] Other works include The Mohammedan Dynasties[129] by Stanley Lane-Poole and Bréhier's Crusades (Bibliography and Sources),[130] a concise summary of the historiography of the Crusades.

References

[編集]- ^ “Fifth Crusade (1217-1221)”. erenow.org. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Wolff 1969, pp. 189–190, Foundation of the Latin Empire.

- ^ a b Michaud 1881, pp. 185–311, Volume II, Book XII: Sixth Crusade.

- ^ Goldsmith, Linda (2006). In The Crusades – An Encyclopedia. pp. 690–691.

- ^ Archer 1904, p. 373, John de Brienne.

- ^ Barker 1923, p. 75, The Fifth Crusade, 1218–1221.

- ^ "Summons to a Crusade, 1215". Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Fordham University. pp. 337–344.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, pp. 612–617, Summoning the New Crusade, 1213–1215.

- ^ "Fourth Lateran Council (1215)". In Catholic Encyclopedia (1913). New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Powell 1986, pp. 67–88, Recruitment for the Crusade.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 382–383, The Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Perry 2013, p. 80, Ruling from Acre to Tyre.

- ^ Smith, Thomas W. (2013). "Pope Honorius III and the Holy Land Crusades, 1216–1227: A Study in Responsive Papal Government“. Ph.D thesis, University of London.

- ^ Slack 2013, p. 175, Pelagius.

- ^ Longnon 1978, p. 213, Gautier, eveque d' Autun.

- ^ Bréhier, Louis (1910). "Jacques de Vitry". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Hoogeweg, Hermann (1887). "Oliver von Paderborn". In Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). 24. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin.

- ^ Reinaud 1826, p. 5, Ibn al-Athir, translated from the Arabic.

- ^ Fulton 2018, pp. 205–218, The Fifth Crusade and New Latin Technology.

- ^ Powell 2006, p. 430, The Course of the Crusade.

- ^ Villegas-Aristizábal 2021, pp. 82–89.

- ^ Barroca 2006, pp. 979–984, Portugal; Villegas-Aristizábal 2019, pp. 59–64.

- ^ Wilson 2021, p. 87.

- ^ Villegas-Aristizábal 2021, pp. 96–103, The Crusaders' Delay, 1217.

- ^ Mikaberidge 2006, pp. 511–513, Kingdom of Georgia.

- ^ Cahen 1969, pp. 715–719, Mongols and the Near East.

- ^ Lane-Poole 1901, pp. 215–216, Saladin's Successors (The Ayyubids), 1193–1250.

- ^ a b Gibb 1969, pp. 697–699, Al-Adil.

- ^ Cahen 1968, pp. 120–125, Turkey in Asia Minor.

- ^ Alexander Mikaberidze: Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1, p. 311

- ^ Veszprémy 2002, pp. 98–99, The Campaign.

- ^ a b Van Cleve 1969, pp. 387–388.

- ^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 133.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 147–148.

- ^ a b Richard 1999, pp. 295–299, Innocent III and the Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Thomas Keightley, Dionysius Lardner: Outlines of history: from the earliest period to the present time, p. 210

- ^ Koch 1885, pp. 23–33, Hermann von Salza: Fünften Kreuzzug.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 388–389, The Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 389–390, The Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 390–391, The Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 391–392, The Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Fulton 2018, pp. 206–207, Mount Tabor (1217).

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 392–393, The Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Veszprémy 2002, pp. 101–103, On the way Home.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, pp. 628–629, War in the East.

- ^ a b The Fifth Crusade, 1218–1221. Map by the University of Wisconsin Cartography Laboratory, facing p. 487 of Volume II of A History of the Crusades (Setton, editor)

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 551–553, The Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Maalouf 2006, pp. 223–224, The Perfect and the Just.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 151–152, The Crusade Lands in Egypt, 1218.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 397–428, The Capture and Loss of Damietta.

- ^ Fulton 2018, pp. 207–218, Damietta (1218–1219).

- ^ Archer 1904, p. 353, Siege Castles.

- ^ a b Van Cleve 1969, pp. 400–401, The Chain Tower.

- ^ Humphreys 1977, pp. 161–163, Al-Mu'azzam 'Isa: The period of independent sovereignty.

- ^ Tyerman 1996, p. 97, The Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, pp. 634–635, War in the East.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 405–406, A Disastrous Storm.

- ^ Cahen 2012, pp. 796–807, Ayyūbids (genealogical table).

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 157, 492, Occupation of al-Adiliya, 1219, cf. Appendix III.1/5.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 410–412, Prelude to the Siege.

- ^ Moses 2009, pp. 16–17, Outfitted to Kill.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 412–414, Prelude to the Siege.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, pp. 639–640, War in the East.

- ^ Slack 2013, p. 96, Francis of Assisi.

- ^ Paschal Robinson (1909). "St. Francis of Assisi". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Maier 1998, pp. 9–11, St Francis and the Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Oliphant 1907, p. 165, The Expedition to Syria.

- ^ Moses 2009, pp. 126–147, The Saint and the Sultan.

- ^ Tolan 2009, p. 160, The Sultan Converted.

- ^ Tolan 2009, pp. 19–39, Francis, Model for the Spiritual Renewal of the Church.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 416–418, The Siege of Damietta.

- ^ Lane-Poole 1901, pp. 221–222, Siege of Damietta.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 161–163, Al-Kamil offers Peace-terms (1219).

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 418–421, Victory at Damietta.

- ^ Guillaume de Chartres (died 1218). The Templar Order (2020).

- ^ Perry 2013, pp. 111–115, The Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 171–172, The Armenian Succession.

- ^ Furber 1969, pp. 609–610, John and the Cypriots.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 164–165, King John leaves the Army (1220).

- ^ Fulton 2018, pp. 216–217, The Push to Mansura.

- ^ Humphreys 1977, p. 167.

- ^ Jackson 2002, The conquest of Iran.

- ^ a b Van Cleve 1969, pp. 421–424, The conquerors at Damietta.

- ^ Christie 2014, Document 16: Al-Kamil Muhammad and the Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, pp. 641–643, War in the East.

- ^ Stockmann, Alois (1911). "Prester John–Second Stage". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Mylod 2017, pp. 53–67, The impact of Prester John on the Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Foltz, Richard C. (1999). Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Exchange from Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century. pp. 111–112. New York: St. Martin's Press. [要ISBN]

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 166–167, The Crusaders Advance (1221).

- ^ Coureas 2017, pp. xxiii, Map of the Nile Delta.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 425–428, Mansurah.

- ^ Maalouf 2006, pp. 225–226, The Perfect and the Just.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, pp. 643–649, The Failure of the Egypt Campaign.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 168–170, Pelagius Sues for Peace (1221).

- ^ Donovan 1950, pp. 69–97, Failure of the Crusade.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969, pp. 427–428, The Surrender.

- ^ Kaye, Haley Caroline, "The Troubadours and the Song of the Crusades" (2016).

- ^ Mylod 2017, pp. 5–12, The historiography of the Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Jacques Bongars. Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 204.

- ^ Mylod 2017, pp. 163–174, Ernoul, Eracles and the Fifth Crusade.

- ^ Bird, Jessalynn. "James of Vitry (died 1240)". The Crusades – An Encyclopedia.

- ^ Jessalynn. "Oliver of Paderborn (died 1227)". The Crusades – An Encyclopedialast=Bird. pp. 898–899.

- ^ Villegas-Aristizábal 2021, pp. 110–149.

- ^ Ruch, Lisa M. (2016). "Roger of Wendover". Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle.

- ^ Giles, J. A. (John Allen) (1849). Roger of Wendover's Flowers of history. London: H. G. Bohn.

- ^ Gesta Crucigerorum Rhenanorum. Part II of Quinti belli sacri scriptores minores sumptibus (1879). Edited by Reinholt Röhricht. pp. 27–56.

- ^ Powell, James M. (translator) (2004). The Deeds of Pope Innocent III. Catholic University of America Press.

- ^ Donnadieu, Jean. "Narratio patriarcae. The origin and destiny of a story about the Muslim Middle East circa 1200", Le Moyen Age, Vol. CXXIV, No. 2, 2018, pp. 283–305.

- ^ Edition in Wilson 2021.

- ^ Cassidy-Welch 2019, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Kennedy, Hugh. "Ibn al-Athir (1160–1233)". The Crusades – An Encyclopedia. p. 625.

- ^ Antrim, Zayde, “Abū Shāma Shihāb al-Dīn al-Maqdisī”. In: Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd Edition. Kate Fleet, et al. (ed.)

- ^ Kreckel, Manuel (2016). "Abū al-Fidā". Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle.

- ^ al-Maqrīzī, A. ibn ʻAlī. (1845). Histoire des Sultans Mamlouks de l'Égypte. Paris.

- ^ Coureas 2017, pp. 185–192, Chronicle of Amadi.

- ^ Röhricht, R. (1879). Quinti belli sacri scriptores minores sumptibus Societatis illustrandis Orientis latini monumentis. Osnabrück, Austria.

- ^ Röhricht, R. (1882). Testimonia minora de quinto bello sacro e chronicis occidentalibus. Genevae.

- ^ Röhricht 1884, pp. 12–14, Annales de Terre Sainte.

- ^ Stephen, Leslie (1889). "Thomas Fuller". In Dictionary of National Biography. 20. London. pp. 315–320.

- ^ Fuller 1639, pp. 160–169, A most promising Voyage into Palestine.

- ^ Bréhier, Louis René (1911). "Joseph-François Michaud". In Catholic Encyclopedia. 10. New York.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Reinaud, Joseph Toussaint". Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 55.

- ^ Reinaud 1826, pp. 5–68, History of the Sixth Crusade and the Capture of Damietta.

- ^ Woods, Gabriel Stanley (1912). "Cox, George William". In Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 Supplement. Volume I. London. p. 221.

- ^ Cox 1891, pp. 176–184, The Sixth Crusade.

- ^ Bréhier, Louis René (1908). "Crusades". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Barker, Ernest (1911). "Crusades". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press. pp. 524–552.

- ^ Schaff, Philip (1884). “Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge”. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Lane-Poole 1894, The Mohammedan Dynasties.

- ^ Bréhier, Louis René (1908). "Crusades (Sources and Bibliography)". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Bibliography

[編集]- Abulafia, David (1992). Frederick II: A Medieval Emperor. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195080408

- Archer, Thomas Andrew (1904). The Crusades: The Story of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Putnam

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1849836883

- Barker, Ernest (1923). The Crusades. World's manuals. Oxford University Press, London

- Barroca, Mário Jorge (2006). Portugal. The Crusades – An Encyclopedia, pp. 979–984

- Bird, Jessalyn (2006). Damietta. The Crusades – An Encyclopedia, pp. 343–344

- Brady, Kathleen (2021). Francis and Clare: the Struggles of the Saints of Assisi. Lodwin Press, New York. ISBN 978-1565482210

- Cahen, Claude (1968). Pre-Ottoman Turkey. Taplinger Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1597404563

- Cahen, Claude (1969). Mongols and the Near East. A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II

- Cahen, Claude (2012). Ayyūbids (2nd ed.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. ISBN 978-9004161214

- Cassidy-Welch, Megan (2019). War and Memory at the Time of the Fifth Crusade. Pennsylvania State University Press

- Christie, Niall (2014). Muslims and Crusaders: Christianity's Wars in the Middle East, 1095–1382, from the Islamic Sources. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138543102

- Coureas, Nicholas (2017). “The Events of the Fifth Crusade according to the Cypriot Chronicle of "Amadi"”. Crusades – Subsidia 9 Chapter 13 185–192 (The Fifth Crusade in Context, Mylod (ed.)).

- Cox, George William (1891). The Crusades. Epochs of history. Longmans, London

- Delaville Le Roulx, Joseph (1904). Les Hospitaliers en Terre Sainte et à Chypre (1100–1310). E. Leroux, Paris

- Donovan, Joseph P. (1950). Pelagius and the Fifth Crusade. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1512801491

- Érszegi, Géza; Solymosi, László (1981). “Az Árpádok királysága, 1000–1301 [The Monarchy of the Árpáds, 1000–1301]”. In Solymosi, László (ハンガリー語). Magyarország történeti kronológiája, I: a kezdetektől 1526-ig [Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: From the Beginning to 1526]. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 79–187. ISBN 963-05-2661-1

- Fuller, Thomas (1639). The Historie of the Holy Warre. W. Pickering, London

- Fulton, Michael S. (2018). Artillery in the Era of the Crusades. Brill Publications. ISBN 978-9004349452

- Furber, Elizabeth Chapin (1969). The Kingdom of Cyprus, 1191–1291. A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1969). The Aiyūbids. A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II

- Humphreys, R. Stephen (1977). From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus, 1193–1260. State University of New York. ISBN 978-0873952637

- Humphreys, R. Stephen (1987). Ayyubids. Encyclopedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 2, pp. 164–167

- Jackson, Peter (2002). Mongols. Encyclopedia Iranica

- Koch, Adolf (1885). Hermann von Salza, Meister des deutschen Ordens. Verlag von Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig

- Lane-Poole, Stanley (1894). The Mohammedan dynasties: chronological and genealogical tables with historical introductions. A. Constable & Co., Westminster

- Lane-Poole, Stanley (1901). History of Egypt in the Middle Ages. A History of Egypt; v. 6. Methuen, London. ISBN 978-0790532042

- Lock, Peter (2006). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203389638. ISBN 0415393124

- Longnon, Jean (1978). Les compagnons de Villehardouin: Recherches sur les croisés de la quatrième croisade. Librairie Droz

- Maalouf, Amin (2006). The Crusades through Arab Eyes. Saqi Books. ISBN 978-0863560231

- Madden, Thomas F. (2013). The Concise History of the Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442215764

- Maier, Christoph T. (1998). Preaching the Crusades: Mendicant Friars and the Cross in the Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521452465

- Michaud, Joseph François (1881). The History of the Crusades (Histoire des Croisades). George Routledge and Sons, London

- Mikaberidge, Alexander (2006). Georgia. The Crusades – An Encyclopedia. pp. 511–513

- Mills, Charles (1820). History of the Crusades for the Recovery and Possession of the Holy Land. Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown

- Moses, Paul (2009). The Saint and the Sultan: The Crusades, Islam, and Francis of Assisi's Mission of Peace. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385523707

- Murray, Alan V. (2006). The Crusades – An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576078624

- Mylod, M. J. (2017). The Fifth Crusade in Context: The Crusading Movement in the Early Thirteenth Century. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315574059. ISBN 978-0367880354

- Nicolle, David (2006). Mansurah. The Crusades – An Encyclopedia, pp. 794–795

- Oliphant, Margaret (1907). Francis of Assisi. Macmillan, London

- Perry, Guy (2013). John of Brienne: King of Jerusalem, Emperor of Constantinople, c. 1175–1237. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107043107

- Powell, James M. (1986). Anatomy of a Crusade, 1213–1221. University of Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-0812213232

- Powell, James M. (2006). Fifth Crusade (1217–1221). The Crusades – An Encyclopedia. pp. 427–432

- Reinaud, Joseph Toussaint (1826). Histoire de la sixième croisade et de la prise de Damiette. Dondey-Dupré

- Richard, Jean C. (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071 – c. 1291. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521625661

- Röhricht, Reinhold (1884). Annales de Terre Sainte, 1095–1291. E. Leroux, Paris

- Röhricht, Reinhold (1891). Studien zur Geschichte des fünften Kreuzzuges. Wagner, Innsbrück

- Roy, J. J. E. (1853). Histoire des Templiers. A. Mame, Tours

- Runciman, Steven (1954). A History of the Crusades, Volume Three: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521347723

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1969). A History of the Crusades. Six Volumes. University of Wisconsin Press

- Slack, Corliss K. (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Crusades. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810878303

- Tolan, John V. (2009). Saint Francis and the Sultan: The Curious History of a Christian-Muslim Encounter. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199239726

- Tyerman, Christopher (1996). England and the Crusades, 1095–1588. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226820122

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674023871

- Van Cleve, Thomas C. (1969). The Fifth Crusade. A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II

- Villegas-Aristizábal, Lucas (2019). Was the Portuguese Led Military Campaign Against Alcácer do Sal in the Autumn of 1217 Part of the Fifth Crusade?, Al-Masāq: Journal of the Medieval Mediterranean, 29 Issue 1. pp. 50–67. doi:10.1080/09503110.2018.1542573

- Villegas-Aristizábal, Lucas (2021). “A Frisian Perspective on Crusading in Iberia as Part of the Sea Journey to the Holy Land, 1217–1218, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History, 3rd Series 15”. Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History: 67–149.

- Veszprémy, László (2002). The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217–1218. Iacobus

- Weiler, Björn K. U. (2006). "Frederick II of Germany". The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. pp. 475–477.

- Wilson, Jonathan, ed (2021). The Conquest of Santarém and Goswin's Song of the Conquest of Alcácer do Sal: Editions and Translations of De expugnatione Scalabis and Gosuini de expugnatione Salaciae carmen. Crusade Texts in Translation. Routledge

- Wolff, Robert Lee (1969). The Latin Empire of Constantinople, 1204–1312. A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II