利用者:Kamokichi/sandbox

| Kamokichi/sandbox | |

|---|---|

| 類型: | shorthand |

| 言語: | Latin |

| 発明者: | Marcus Tullius Tiro 60s BC |

| 時期: | 1st century BC – 16th century AD |

| 状態: | some Tironian symbols still in modern use |

| Unicode範囲: | Et: U+204A; MUFI |

| 注意: このページはUnicodeで書かれた国際音声記号 (IPA) を含む場合があります。 | |

ティロの速記 (ラテン語: notae Tironianae) は、 キケロの奴隷、秘書、解放奴隷であったマルクス・トゥリウス・ティロ (94 – 4 BC)によって発明された 速記の方式である。[1] ティロの速記は約4,000の符号で構成されたが、[要出典] 古代ローマ時代にはその数が5,000まで増えた。 中世の間には、ティロの速記はヨーロッパの修道院で教えられ、符号の数はさらに約13,000まで増えた。[2] ティロの速記は1100年以降衰退したが、そのうちのいくつかは17世紀になっても使用されており、今日でもごく少数ながら使用されているものもある。[3][4]

符号数に関する注意

[編集]

ティロの速記は、言葉をより短く書き表すために、いくつかの単純な符号を組み合わせた符号(省略符号)を使っている。このことは、 証言された符号の数が多いこと、および符号の総数の推定値にばらつきが大きいことの原因の一つである。さらに、「同じ」符号にいくつかバリエーションがあることも、同じ問題を引き起こしている。

歴史

[編集]開発

[編集]歴史家によって「速記の父」と呼ばれた[3] ティロ (94 BC – 4 AD) は、キケロ (106 – 43 BC)の奴隷であり、のちに解放奴隷となった個人秘書である。ティロは、彼と同じ立場にあった者と同様、キケロの発言(例えば、演説や職業上ないし個人的なやりとり、あるいは商取引の交渉など)をすばやく正確に書き取ることが求められた。時には公開広場を歩きながらであったり、展開が早く、議論になる政治や裁判手続の間ということもあった。[5]

当時のラテン語で体系化された唯一の省略記述法は、法的表記法(notae juris)に使用されていたが、意図的に難解にされ、専門的な知識を持つ人々にしかアクセスできないようにされていた。別な方法としては、速記はメモをとったり個人的な会話を書き取るために即興でするしかなく、このような速記法は閉鎖的なコミュニティーの中でしか理解されることのできないものだった。 記念碑に刻まれているものなど、ラテン語の単語やフレーズを速記したものの一部は一般的に認識されていたが、文学教授のAnthony Di Renzoいわく、「この時点において、本物のラテン語の速記法は存在しなかった」のである。[5]

学者が信じるところにれば、キケロは、ギリシャ語速記法の複雑さを知った後、包括的かつ標準的なラテン語速記法の必要性を認識し、その使命を彼の奴隷であったティロに託した。そして、ティロの速記は非常に洗練され、正確であったため、彼の速記法は標準化され広く採用された最初のラテン語速記法となった。 ティロの速記 (notae Tironianae) は、ラテン文字の略字、ティロが考案した抽象的な符号、およびギリシャ語速記法から借用した符号で構成される。ティロの速記は、前置詞 、省略した単語、縮約、 音節、活用を表すことができた。Di Renzoによれば、「ティロは、フレーズだけでなく、キケロがアッティクスへの手紙の中で感嘆したように、『すべての文』を記録するため、楽譜の音符のようにこれらの符号を組み合わせたのだ」[5]

Controversy

[編集]Dio Cassius attributes the invention of shorthand to Maecenas, and states that he employed his freedman Aquila in teaching the system to numerous others.[6] Isidore of Seville, however, details another version of the early history of the system, ascribing the invention of the art to Quintus Ennius, who he says invented 1100 marks (ラテン語: notae). Isidore states that Tiro brought the practice to Rome, but only used Tironian notes for prepositions.[7] According to Plutarch in "Life of Cato the Younger" (1683), Cicero's secretaries established the first examples of the art of Latin shorthand:

This only of all Cato's speeches, it is said, was preserved; for Cicero, the consul, had disposed in various parts of the senate-house, several of the most expert and rapid writers, whom he had taught to make figures comprising numerous words in a few short strokes; as up to that time they had not used those we call shorthand writers, who then, as it is said, established the first example of the art.—Plutarch、"Life of Cato the Younger"[8]

Introduction

[編集]There are no surviving copies of Tiro's original manual and code, so knowledge of it is based on biographical records and copies of Tironian tables from the medieval period.[5] Historians typically date the invention of Tiro's system as 63 BC, when it was first used in official government business according to Plutarch in his biography of Cato the Younger in The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans (1683).[9] Before Tiro's system was institutionalized, he used it himself as he was developing and fine-tuning it, which historians suspect may have been as early as 75 BC when Cicero held public office in Sicily and needed his notes and correspondences to be written in code to protect sensitive information he had gathered about corruption among other government officials there.[5]

There is evidence that Tiro taught his system to Cicero and his other scribes, and possibly to his friends and family, before it was widely used. In "Life of Cato the Younger", Plutarch wrote that during Senate hearings in 65 BC relating to the first Catilinarian conspiracy, Tiro and Cicero's other secretaries were in the audience meticulously and rapidly transcribing Cicero's oration. On many of the oldest Tironian tables, lines from this speech were frequently used as examples, leading scholars to theorize it was originally transcribed using Tironian shorthand. Scholars also believe that in preparation for speeches, Tiro drafted outlines in shorthand that Cicero used as notes while speaking.[5]

Expansion

[編集]Isidore tells of the development of additional Tironian notes by various hands, viz., Vipsanius, "Philargius", and Aquila (as above), until Seneca systematized the various marks to approximately 5000 Tironian notes.[7]

Use in the Middle Ages

[編集]Entering the Middle Ages, Tiro's shorthand was often used in combination with other abbreviations and the original symbols were expanded to 14,000 symbols during the Carolingian dynasty, but it quickly fell out of favor as shorthand became associated with witchcraft and magic and was forgotten until interest was rekindled by Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury, in the 12th century.[10] In the 15th century Johannes Trithemius, abbot of the Benedictine abbey of Sponheim, discovered the notae Benenses: a psalm and a Ciceronian lexicon written in Tironian shorthand.[11]

Current

[編集]

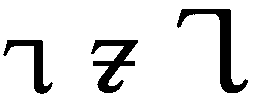

Tironian notes are still used today, particularly the Tironian “et”, used in Ireland and Scotland to mean and (where it is called agus in Irish and agusan[12] in Scottish Gaelic), and in the “z” of “viz.” (for ‘et’ in videlicet—though here the "z" is really a Latin abbreviation sign, encoded as a casing pair U+A76A Ꝫ and U+A76B ꝫ).

In blackletter texts (especially in German printing) it was used in the abbreviation ⟨⁊c.⟩ = etc. (for et cetera) still throughout the 19th century.

The Tironian "et" can look very similar to an r rotunda, ⟨ꝛ⟩, depending on the typeface.

In Old English manuscripts, the Tironian "et" served as both a phonetic and morphological place holder. For instance a Tironian "et" between two words would be phonetically pronounced "ond" and would mean "and". However, if the Tironian "et" followed the letter "s", then it would be phonetically pronounced "sond" and mean water (ancestral to Modern English sound). This additional function of a phonetic as well as a conjunction placeholder has escaped formal Modern English; for example, one may not spell the word "sand" as "s&" (although this occurs in an informal style practised on certain internet forums). This practice was distinct from the occasional use of "&c." for "etc.", where the & is interpreted as the Latin word et ("and") and the "c." is an abbreviation for Latin cetera ("(the) rest").

Support on computers

[編集]It is not easy to use Tironian notes on modern computing devices.

The Tironian et ⟨⁊⟩ ("and") is available at Unicode point U+204A, and can be made to display (e.g. for documents written in Irish or Scottish Gaelic) on a relatively wide range of devices: on Microsoft Windows, it can be shown in Segoe UI Symbol (a font that comes bundled with Windows Vista onwards); on macOS and iOS devices in Helvetica; and on Windows, macOS, Google Chrome OS, and Linux in the free DejaVu Sans font (which comes bundled with Chrome OS and various Linux distributions).

Some applications and websites, such as the online edition of the "Dictionary of the Irish Language", substitute the Tironian et with the box-drawing character U+2510 ┐, as it looks similar and displays widely. The numeral 7 is also used in informal contexts such as Internet forums and occasionally in print.[13]

A number of other Tironian signs have been assigned to the Private Use Area of Unicode by the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (MUFI),[疑問点] who also provide links to free typefaces that support their specifications.

Gallery

[編集]-

Psalm 68. Manuscript, 9th century

-

Tironian note glossary from the 8th century, codex Casselanus

-

Tironian et in the abbreviation "etc." at the end of the nobility title list. German printing, 1768

See also

[編集]References

[編集]- ^ Di Renzo, Anthony (2000), “His Master's Voice: Tiro and the Rise of the Roman Secretarial Class”, Journal of Technical Writing & Communication 30 (2) 31 July 2016閲覧。

- ^ Guénin, Louis-Prosper; Guénin, Eugène (1908) (French), Histoire de la sténographie dans l'antiquité et au moyen-âge; les notes tironiennes, Paris, Hachette et cie, OCLC 301255530

- ^ a b Mitzschke, Paul Gottfried; Lipsius, Justus; Heffley, Norman P (1882), Biography of the father of stenography, Marcus Tullius Tiro. Together with the Latin letter, "De notis", concerning the origin of shorthand, Brooklyn, N.Y, OCLC 11943552

- ^ Kopp, Ulrich Friedrich; Bischoff, Bernhard (1965) (German), Lexicon Tironianum, Osnabrück, Zeller, OCLC 2996309

- ^ a b c d e f Di Renzo, Anthony (2000), “His Master's Voice: Tiro and the Rise of the Roman Secretarial Class”, Journal of Technical Writing & Communication 30 (2) 31 July 2016閲覧。

- ^ Dio Cassius. Roman History. 55.7.6

- ^ a b Isidorus. Etymologiae or Originum I.21ff, Gothofred, editor

- ^ Plutarch John Dryden訳 (1683), “Life of Cato the Younger”, The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans

- ^ Bankston, Zach (2012), “Administrative Slavery in the Ancient Roman Republic: The Value of Marcus Tullius Tiro in Ciceronian Rhetoric”, Rhetoric Review 31 (3): 203–218, doi:10.1080/07350198.2012.683991

- ^ Russon, Allien R. (n.d.), “Shorthand”, Encyclopædia Britannica Online 1 August 2016閲覧。

- ^ David A. King, The ciphers of the monks: a forgotten number-notation of the Middle Ages

- ^ “Am Faclair Beag - Scottish Gaelic Dictionary”. www.faclair.com. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Cox, Richard (1991). Brìgh nam Facal. Roinn nan Cànan Ceilteach. p. V. ISBN 978-0903204-21-7

External links

[編集]- Wilhelm Schmitz: Commentarii notarum tironianarum, 1893 (Latin)

- Émile Chatelain: Introduction à la lecture des notes tironiennes, 1900 (French)

- Karl Eberhard Henke: Über Tironische Noten Manuscript B 16 of the "Bibliothek der Monumenta Germaniae Historica", c. 1960 (German) (See 33. within for examples of composite Tironian notes.)

- Martin Hellmann: Supertextus Notarum Tironianarum Online dictionary of Tironian notes, based on Schmitz 1893 (German)