利用者:Sarandora/試訳中記事2

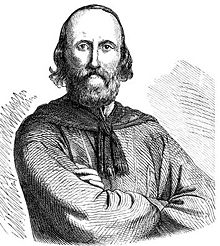

ジュセッペ・ガリバルディ Giuseppe Garibaldi | |

|---|---|

ギュスターヴ・ル・グレイによる肖像写真(1860年) | |

| 生誕 |

Joseph Marie Garibaldi ジュセッペ・マリーア・ガリバルディ 1807年7月4日 プロヴァンス地方、ニース |

| 死没 |

1882年6月2日(74歳没) サルデーニャ地方、カプレーラ |

| 死因 | 病没 |

| 記念碑 | ガリバルディ像(ローマ)、ガリバルディ街道(ジェノヴァ)、ガリバルディ記念像(ジャニコロ丘)、ガリバルディ記念像(ワシントン)、スタテン島記念館(ニューヨーク)、ガリバルディ記念像(タガンログ)、ガリバルディ記念館(モンテビデオ)、ガリバルディ騎馬像(ブエノスアイレス)他 |

| 別名 |

イタリア三英傑 二つの世界の英雄[1] |

| 民族 | イタリア |

| 市民権 | フランス、アメリカ、イタリア |

| 職業 | 船長、傭兵隊長、軍人、政治家 |

| 団体 | 赤シャツ隊 |

| 著名な実績 | リソルジメント |

| 影響を受けたもの | ジュゼッペ・マッツィーニ |

| 影響を与えたもの | ジェシー・ホワイト、スバス・チャンドラ・ボース、ゲオルギオス・グリヴァス、チェ・ゲバラ、ベニート・ムッソリーニ |

| 宗教 | 無神論 |

| 子供 | リッチョッティ・ガリバルディ |

| 署名 | |

|

| |

ジュゼッペ・ガリバルディ(イタリア語発音: [dʒuˈzɛppe ɡariˈbaldi]、1807年7月4日 - 1882年6月2日)は近代イタリアの政治家、軍人、革命家。

19世紀における数多くの民族自決運動に関わりを持ち、傭兵や義勇軍を率いて世界中を転戦した。特に父祖の地であるイタリアの統一運動(リソルジメント)に貢献した事から、カミッロ・カヴール伯爵、ジュゼッペ・マッツィーニらと共に「イタリア三英傑」と呼ばれる。また南米での革命戦争(大戦争)でも大きな役割を示し、「二つの世界の英雄」とも尊称されている[2]。岡倉天心は欧州に向けた著作の中で西郷隆盛を「日本のガリバルディ」と解説した[3]。彼の勇敢な行動と成功は世界中の賛美を集め、ヴィクトル・ユーゴー、アレクサンドル・デュマ・ペール、ジョルジュ・サンドらがガリバルディの偉業を讃える言葉を残した。またイギリスとアメリカは国を挙げてガリバルディを支援し、彼の革命と亡命生活を助けていた。

ガリバルディの思想はフランス革命を理想視するカルボナリ、及び民族自決を重んじてカルボナリから離脱した青年イタリア党の運動を通じて培われた。彼は民族主義の精神と社会主義の理念を合わせ持ち、第一インターナショナルの参加名簿にもミハイル・バクーニンやカール・マルクスらと名を連ねている。しかし一方で彼は基本的に合法的権力から逸脱した陰謀や策動を好まず、常に正規の軍事行動によって目標を達成しようと試みた。この点から彼を革命家として含めるかは議論が存在する。

生涯

[編集]船乗りから革命家へ

[編集]1807年7月4日、ジュゼッペ・マリーア・ガリバルディ(Joseph Marie Garibaldi)はナポレオン戦争による影響からフランス第一帝政の占領下にあったプロヴァンス地方の港ニースに、ジョヴァンニ・ドメニコ・ガリバルディ(Giovanni Domenico Garibaldi)[4]とマリア・ローサ・ニコレッタ・ライモンド(Maria Rosa Nicoletta Raimondo)[5]の子として生まれた。1814年、彼が7歳の時にナポレオンは降伏に追い込まれ、ウィーン会議によってニースは元の支配国であるサルデーニャ・ピエモンテ王国(サヴォイア家)の領域に戻った。ニースは伝統的に複数の文化圏(フランス、イタリア、オック等)が交差する港町として繁栄を得て来た歴史があり、近代に民族主義や国民国家の概念が広がる中で複雑な立場に置かれていた。その中でもガリバルディはニース・イタリア人としての帰属心を抱いていた。

ガリバルディ家は初代当主ステファーノ・ガリバルディの代から貿易業を生業とする一族であり、彼も自然と船乗りとして身を立てる様になった。ガリバルディは見習い水夫として様々な航海を経て、1832年に自らの船を持ち商船隊の指揮官となった。商船を率いて地中海各地を巡る中、黒海での貿易に携わった事が彼の運命を動かした。1833年4月、ロシア帝国領タガンロクを果実輸出の為に立ち寄った時に亡命イタリア人のジョヴァンニ・バッティスタ・クーネオと意気投合したガリバルディは、彼の推薦を受けて青年イタリア党への参加を勧められる。青年イタリア党は共和主義者の秘密結社であるカルボナリを前身とし、その上で民族自決の概念を軽視する同組織を見限った者達が結成した組織であった。

1833年11月、ガリバルディはイタリア沿岸部に戻ると党首ジュゼッペ・マッツィーニと面会し、その人生をオーストリアの支配をうける祖国イタリアの自由のために戦う事を誓った。同時に青年イタリア党と協力という形で関与を続けていたカルボナリにも入党を許されている。そして翌年の1834年2月にマッツィーニが指導した大規模なサルデーニャ・ピエモンテ王国領ジェノヴァ(旧ジェノヴァ共和国、ウィーン会議で同国に併合される)での反乱に加わるが、秘密主義的な陰謀に彼の実直な気性は向いておらず、理想家であったマッツィーニの計画も現実味を欠いていた。同年に起こされた反乱は王国軍によって短期間に鎮圧され、マッツィーニら幹部は再度の亡命を強いられた。また国際革命を目指すカルボナリと青年イタリア党の対立も先鋭化していった。

ガリバルディにも追っ手が送られ、南仏に逃れた後も拘束と脱獄を繰り返しながらマルセイユに辿り着いた。その間にも欧州各地で反王政の共和主義反乱と凄惨な鎮圧が繰り返され、やがてガリバルディにも欠席裁判で死刑が宣告される。1835年、ヨーロッパ世界から他の大陸への亡命を決意したガリバルディは南米へと向かうべく密航する。

南米での日々

[編集]

1836年、長い航海を経てガリバルディは南米の地で独立勢力を持つブラジル帝国へと辿り着いた。同地ではイタリア各地からの移民者が殖民市を形成しており、青年イタリア党の在外組織も存在していた事から亡命先としては十分であった。

当時、ブラジル帝国は殖民元であったポルトガル王国のブラサンガ王家からの流れを持つ異郷出身の皇帝ペードロ1世がナポレオン戦争に対抗する先住民の旗印として帝位に就いていた。だがナポレオン失脚後、ペードロ1世は失政を繰り返して民衆の支持を失い、さらに夫よりもブラジルの未来を案じていた皇妃マリア・レオポルディナ・デ・アウストリアが冷遇の末に早世した事で反感は一層に高まっていた。1841年7月18日、ポルトガル本国で内戦が起きた事に驚愕したペドロ1世はブラジルを捨てて帰国すると混乱は頂点に達し、ガウチョ(先住民と入植民との混血者)による反乱であるファラーポス戦争が発生した。

ガリバルディは戦争の中で独立を宣言したリオ・グランデ共和国に共和主義の義勇兵として加わり、青年イタリア党の兵士や船を率いてブラジル帝国軍及びこれを支援する隣国(ウルグアイ、アルゼンチン)と戦った。彼は幾つかのブラジル船を拿捕したり、解放した奴隷や兵士を仲間に加えながら戦力を拡大するなど軍事的才覚を示した。理論家肌のマッツィーニに比べて、こうした山賊の親分の様な生活は彼の気質に向いていた。1837年、ラプラタ川海域を航行中にウルグアイ軍の攻撃で負傷した際、同国と敵対する隣国アルゼンチンの専制的な独裁者フアン・マヌエル・デ・ロサスから治療名目で軟禁される。ガリバルディはファラーポス戦争に復帰しようと脱獄を試みた事で激怒したロサスによる拷問を受けるが、再び脱獄してウルグアイ領内に潜伏した。ウルグアイで傷を癒しながら志願兵を集め、リオ・グランデ軍の一隊として森林地帯や海路を利用したゲリラ戦術を行った。

1839年、占領下に置いた漁村の一つで知り合ったポルトガル系の未亡人アンナ・マリア・リベイロ・ダ・シルヴァとの間に長男メノッティ・ガリバルディ(Menotti Garibaldi)、次男リッチョティ・ガリバルディ(Ricciotti Garibaldi)を儲ける。彼女は血気盛んな女戦士として名を馳せ、アマゾネスの異名で知られていた。その後もガリバルディはリオ・グランデ軍の指揮官として戦うが、富裕層が独占する共和国の現実に失望感を抱いて離脱する。1842年、南米での紛争に欧州列強が介入する一方、戦争は新たな局面を迎えた。アルゼンチンがウルグアイ内の親アルゼンチン派(ブランコ党軍)に反乱を嗾け(大戦争)、劣勢を強いられたウルグアイの反アルゼンチン派(コロラド党軍)は実績を持つガリバルディを傭兵隊長として招致する。

コロラド党軍の大佐となったガリバルディは包囲下に置かれたモンテビデオ防衛に参加、フランス系移民とイタリア系移民の指揮を任される。雑多な市民兵でしかなかった部隊をリオグランデ軍時代に培った経験で纏め上げ、規律の一環として赤シャツを制服として配給した。1846年、ガリバルディ隊180名はコロラド党軍の防衛作戦において巧みなゲリラ戦術を展開し、ブランコ党軍とアルゼンチン軍の兵士1500名を撃退して勇名を馳せた。戦勝に対してウルグアイ政府はガリバルディ隊への恩賞として土地の配給を決定したが、ガリバルディは「ウルグアイの自由が守られれば、それが部隊の報酬となる」として丁重に辞退した。

彼の戦いはヨーロッパにも届き、後にアレクサンドル・デュマ・ペールが『新しきトロイア』の題名で伝記を記している。また戦いの最中に本国で教皇領を機転としたイタリア統一運動が始まると、ガリバルディはこれを賞賛する手紙を残している[6]。統一運動を支持する人々はガリバルディの存在を期待するようになり、死罪宣告の状態を理解しつつも民衆の声に応えるべくガリバルディは帰国を決意する。

イタリアへの帰還

[編集]第一次イタリア独立戦争

[編集]

統一運動はウィーン体制という旧弊に立ち向かおうとした1848年革命を背景としていたが、彼が帰還を遂げた時にはパリ蜂起の弾圧など沈静化に向かいつつあった。それでもイタリア諸侯はハプスブルグ領内での反乱を支援すべく同盟を結び、ハプスブルグ君主国にイタリアの解放を賭けた決戦を挑もうとしていた(第一次イタリア独立戦争)。しかし旗印として期待されていた教皇ピウス9世は宗教的中立を理由にして統一戦争に不介入の宣言を出し、諸侯の足並みは揃わないままに時間ばかりが過ぎていった。

1848年6月、ガリバルディは故郷ニースに数十人の兵士を連れて上陸、統一戦争の機運に熱狂する民衆の歓呼に迎えられた。情勢を把握したガリバルディは諸侯が動揺する中で唯一戦いを続ける意向を示していたサルデーニャ・ピエモンテ王国に協力する意向を固め、サルデーニャ王カルロ・アルベルトに謁見と従軍を申し出た。共和主義を毛嫌いしていた専制的なアルベルトも南米での戦功で知られるガリバルディを蔑ろには出来ず、かつての死罪を取り消した上で従軍を許可した。だが共和主義的な革命を利用こそすれ信頼していなかったアルベルトは革命軍を冷遇しており、ガリバルディも例外ではなかった。各地で勝利を重ねる一方、革命軍と王国軍は絶えず不協和音の中にあり、進軍は捗らずハプスブルグ軍の戦力回復を許してしまう。

1848年7月23日、カルロ・アルベルト率いるサルデーニャ軍はヨーゼフ・ラデツキー率いるハプスブルグ軍の前に敗北を喫した。そればかりか防衛の準備を進めるガリバルディ達を置いてトリノに帰還してしまい、ヴェネツィアやロンバルディアの反乱軍は見殺しにされた。1849年にブレシアの戦いとヴェネツィアの戦いで二つの反乱軍が壊滅するとアルベルトは単独で決戦に臨み、時機を完全に逸した状態での大敗という結末を招いた。王宮に逃げ戻ったアルベルトはサヴォイア家から追放され、代わって王太子ヴィットーリオがヴィットーリオ・エマヌエーレ2世として即位、ハプスブルグと講和を結んで戦争は終結した。

ローマ共和国

[編集]

しかし革命軍は未だ独立戦争を諦めてはいなかった。ジュゼッペ・マッツィーニは青年イタリア党を通じて各地の共和主義者に結集を呼びかけると、臆病な行動から信望を失ったピウス9世追放後の教皇領を占拠してローマ共和国を建国した。アルプス山脈やアペニン山脈でゲリラ戦を続けていたガリバルディも手勢を引き連れ、ローマに入城する。開催された共和国元老院はマッツィーニを執政官に選び、またガリバルディは元老院議員の一人として軍の編成を一任された。

欧州諸国はフランス革命の再来を恐れ、特にナポレオン3世のフランス第二帝政は教皇領復活を目指した遠征軍を派遣した。フランス軍はローマの強奪者たちを軽んじていたが、ロンバルディアやピエモンテ、リグリアから馳せ参じた義勇兵たちとガリバルディはテヴェレ川西岸のバチカンの南で起こったジャニコロ丘の戦いでフランス軍を破り、敗走させた。しかしマッツィーニが追撃に反対したせいもあって体制を立て直したフランス軍は、数に任せて攻勢を繰り返し、ローマを包囲下に置いた。

1849年6月30日、ジュゼッペ・マッツィーニとガリバルディはアペニン山脈に退いての継戦、ローマ市街地での玉砕、フランス軍への降伏の三択のいずれを選ぶか協議した。ガリバルディは「我々が何処に退こうとも、戦う限りローマは存続する」(Dovunque saremo, colà sarà Roma)[7] と抗戦を主張して、7月2日に4,000人の兵士を連れてローマを脱出した。7月3日、ローマに入城したフランス軍は教皇領を復活させてガリバルディ軍に追撃の軍を送り、ガリバルディは北イタリア各地を転戦しながら中立国へと向かった。

スペイン軍、フランス軍、オーストリア軍、ナポリ軍の追撃の前に多くの兵士が倒れた。妻のアニータも戦場で受けた傷が元で病に倒れ、ラヴェンナで病没した。サンマリノ市の協力にも助けられつつ、苦難を乗り越えながら最終的に250名の兵士と共にサルデーニャ・ピエモンテ王国領へと辿り着いた。

スタテン島での生活

[編集]Garibaldi eventually managed to reach Portovenere, near La Spezia, but the Piedmontese government forced him to emigrate again.

He went to Tangier, where he stayed with Francesco Carpanetto, a wealthy Italian merchant. Carpanetto suggested that he and some of his associates would finance the purchase of a merchant ship, which Garibaldi would command. Garibaldi agreed, feeling that his political goals were for the moment unreachable, and he could at least earn his own living.[8]

The ship was to be purchased in the United States, so Garibaldi went to New York, arriving on 30 July 1850. There he stayed with various Italian friends, including some exiled revolutionaries. However, funds for the purchase of a ship were lacking.

The inventor Antonio Meucci employed Garibaldi in his candle factory on Staten Island.[9] The cottage on Staten Island where he stayed is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places and is preserved as the Garibaldi Memorial.

太平洋航海

[編集]Garibaldi was not satisfied with this. In April 1851 he left New York with his friend Carpanetto for Central America, where Carpanetto was establishing business operations. They went first to Nicaragua, and then to other parts of the region. Garibaldi accompanied Carpanetto as a companion, not a business partner, and used the name "Giuseppe Pane."[8]

Carponetto went on to Lima, Peru, where a ship-load of his goods was due, arriving late in 1851 with Garibaldi. En route, Garibaldi called on Andean revolutionary heroine Manuela Sáenz.

At Lima, Garibaldi was generally welcomed. A local Italian merchant, Pietro Denegri, gave him command of his ship Carmen for a trading voyage across the Pacific. Garibaldi took the Carmen to the Chincha Islands for a load of guano. Then on 10 January 1852, he sailed from Peru for Canton, China, arriving in April.[8]

After side trips to Amoy and Manila, Garibaldi brought the Carmen back to Peru via the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific, passing clear around the south coast of Australia. He visited Three Hummocks Island in Bass Strait.[8]

Garibaldi then took the Carmen on a second voyage: to the United States via Cape Horn with copper from Chile, and also wool. Garibaldi arrived in Boston, and went on to New York. There he received a hostile letter from Denegri, and resigned his command.[8]

Another Italian, Captain Figari, had just come to the U.S. to buy a ship. He hired Garibaldi to take his ship to Europe. Figari and Garibaldi bought the Commonwealth in Baltimore, and Garibaldi left New York for the last time in November 1853.[9] He sailed the Commonwealth to London and then to Newcastle on the River Tyne for coal.[8]

イギリス訪問

[編集]Commonwealth arrived on 21 March 1854. Garibaldi, already a popular figure on Tyneside, was welcomed enthusiastically by local workingmen, although the Newcastle Courant reported that he refused an invitation to dine with dignitaries in the city. He stayed in Tynemouth on Tyneside for over a month, departing at the end of April 1854. During his stay, he was presented with an inscribed sword, which his grandson later carried as a volunteer in British service in the Boer War.[10] He then sailed to Genoa, where his five years of exile ended on 10 May 1854.[8]

リソルジメント

[編集]Garibaldi returned again to Italy in 1854. Using a legacy from the death of his brother, he bought half of the Italian island of Caprera (north of Sardinia), devoting himself to agriculture. In 1859, the Second Italian War of Independence (also known as the Austro-Sardinian War) broke out in the midst of internal plots at the Sardinian government. Garibaldi was appointed major general, and formed a volunteer unit named the Hunters of the Alps (Cacciatori delle Alpi). Thenceforth, Garibaldi abandoned Mazzini's republican ideal of the liberation of Italy, assuming that only the Piedmontese monarchy could effectively achieve it.

With his volunteers, he won victories over the Austrians at Varese, Como, and other places.

Garibaldi was however very displeased as his home city of Nice (Nizza in Italian) was surrendered to the French, in return for crucial military assistance. In April 1860, as deputy for Nice in the Piedmontese parliament at Turin, he vehemently attacked Cavour for ceding Nice and the County of Nice (Nizzardo) to Louis Napoleon, Emperor of France. In the following years Garibaldi (with other passionate Nizzardo Italians) promoted the Italian irredentism of his Nizza, even with riots (in 1872).

1860年の遠征

[編集]

On 24 January 1860, Garibaldi married an 18-year-old Lombard noblewoman, Giuseppina Raimondi. Immediately after the wedding ceremony, however, she informed him that she was pregnant with another man's child and Garibaldi left her the same day.[11]

At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in Messina and Palermo in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies provided Garibaldi with an opportunity. He gathered about a thousand volunteers – called i Mille (the Thousand), or, as popularly known, the Redshirts – in two ships named Piemonte and Lombardo, left from Genoa on 5 May in the evening and landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily, on 11 May.

Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi led 800 volunteers to victory over an enemy force of 1500 on the hill of Calatafimi on 15 May. He used the counter-intuitive tactic of an uphill bayonet charge. He saw that the hill the enemy had taken position on was terraced, and the terraces would give shelter to his advancing men. Though small by comparison with the coming clashes at Palermo, Milazzo and Volturno, this battle was decisive in terms of establishing Garibaldi's power in the island. An apocryphal but realistic story had him say to his lieutenant Nino Bixio, Qui si fa l'Italia o si muore, that is, Here we either make Italy, or we die. In reality, the Neapolitan forces were ill guided, and most of its higher officers had been bought out. The next day, he declared himself dictator of Sicily in the name of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy. He advanced to Palermo, the capital of the island, and launched a siege on 27 May. He had the support of many inhabitants, who rose up against the garrison, but before they could take the city , reinforcements arrived and bombarded the city nearly to ruins. At this time, a British admiral intervened and facilitated an armistice, by which the Neapolitan royal troops and warships surrendered the city and departed.

Garibaldi had won a signal victory. He gained worldwide renown and the adulation of Italians. Faith in his prowess was so strong that doubt, confusion, and dismay seized even the Neapolitan court. Six weeks later, he marched against Messina in the east of the island, winning a ferocious and difficult battle at Milazzo. By the end of July, only the citadel resisted.

Having conquered Sicily, he crossed the Strait of Messina with help from the British Royal Navy, and marched north. Garibaldi's progress was met with more celebration than resistance, and on 7 September he entered the capital city of Naples, by train. Despite taking Naples, however, he had not to this point defeated the Neapolitan army. Garibaldi's volunteer army of 24,000 was not able to defeat conclusively the reorganized Neapolitan army (about 25,000 men) on 30 September at the Battle of Volturno. This was the largest battle he ever fought, but its outcome was effectively decided by the arrival of the Piedmontese Army. Following this, Garibaldi's plans to march on to Rome were jeopardized by the Piedmontese, technically his ally but unwilling to risk war with France, whose army protected the Pope. (The Piedmontese themselves had conquered most of the Pope's territories in their march south to meet Garibaldi, but they had deliberately avoided Rome, his capital.) Garibaldi chose to hand over all his territorial gains in the south to the Piedmontese and withdrew to Caprera and temporary retirement. Some modern historians consider the handover of his gains to the Piedmontese as a political defeat, but he seemed willing to see Italian unity brought about under the Piedmontese crown. The meeting at Teano between Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel II is the most important event in modern Italian history, but is so shrouded in controversy that even the exact site where it took place is in doubt.

イタリア王国成立

[編集]

Garibaldi deeply disliked the Sardinian Prime Minister, Camillo Benso, conte di Cavour. To an extent, he simply mistrusted Cavour's pragmatism and realpolitik, but he also bore a personal grudge for trading away his home city of Nice to the French the previous year. On the other hand, he felt attracted toward the Piedmontese monarch, who in his opinion had been chosen by Providence for the liberation of Italy. In his famous meeting with Victor Emmanuel II at Teano on 26 October 1860, Garibaldi greeted him as King of Italy and shook his hand. Garibaldi rode into Naples at the king's side on 7 November, then retired to the rocky island of Caprera, refusing to accept any reward for his services.

On 5 October Garibaldi set up the International Legion bringing together different national divisions of French, Poles, Swiss, German and other nationalities, with a view not just of finishing the liberation of Italy, but also of their homelands. With the motto "Free from the Alps to the Adriatic," the unification movement set its gaze on Rome and Venice. Mazzini was discontented with the perpetuation of monarchial government, and continued to agitate for a republic. Garibaldi, frustrated at inaction by the king, and bristling over perceived snubs, organized a new venture. This time, he intended to take on the Papal States.

At the outbreak of the American Civil War (in 1861), Garibaldi volunteered his services to President Abraham Lincoln. Garibaldi was offered a Major General's commission in the U.S. Army through the letter from Secretary of State William H. Seward to H. S. Sanford, the U.S. Minister at Brussels, 17 July 1861.[12] On 18 September 1861, Sanford sent the following reply to Seward:

He [Garibaldi] said that the only way in which he could render service, as he ardently desired to do, to the cause of the United States, was as Commander-in-chief of its forces, that he would only go as such, and with the additional contingent power—to be governed by events—of declaring the abolition of slavery; that he would be of little use without the first, and without the second it would appear like a civil war in which the world at large could have little interest or sympathy.[13]

According to Italian historian Petacco, "Garibaldi was ready to accept Lincoln's 1862 offer but on one condition: that the war's objective be declared as the abolition of slavery. But at that stage Lincoln was unwilling to make such a statement lest he worsen an agricultural crisis."[14] On 6 August 1863, after the Emancipation Proclamation had been issued, Garibaldi wrote to Lincoln: "Posterity will call you the great emancipator, a more enviable title than any crown could be, and greater than any merely mundane treasure."[15]

イタリア統一後の日々

[編集]ローマ行軍

[編集]A challenge against the Pope's temporal domain was viewed with great distrust by Catholics around the world, and the French emperor Napoleon III had guaranteed the independence of Rome from Italy by stationing a French garrison in Rome. Victor Emmanuel was wary of the international repercussions of attacking the Papal States, and discouraged his subjects from participating in revolutionary ventures with such intentions. Nonetheless, Garibaldi believed he had the secret support of his government.

In June 1862, he sailed from Genoa and landed at Palermo, seeking to gather volunteers for the impending campaign under the slogan Roma o Morte (Rome or Death). An enthusiastic party quickly joined him, and he turned for Messina, hoping to cross to the mainland there. When he arrived, he had a force of some two thousand, but the garrison proved loyal to the king's instructions and barred his passage. They turned south and set sail from Catania, where Garibaldi declared that he would enter Rome as a victor or perish beneath its walls. He landed at Melito on 14 August, and marched at once into the Calabrian mountains.

Far from supporting this endeavor, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Enrico Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Emilio Pallavicini, against the volunteer bands. On 28 August the two forces met in the rugged Aspromonte. One of the regulars fired a chance shot, and several volleys followed, killing a few of the volunteers. The fighting ended quickly, as Garibaldi forbade his men to return fire on fellow subjects of the Kingdom of Italy. Many of the volunteers were taken prisoner, including Garibaldi, who had been wounded by a shot in the foot.

This episode gave birth to a famous Italian nursery rhyme, still known by boys and girls all over the country: Garibaldi fu ferito ("Garibaldi was wounded").

A government steamer took him to Varignano, a prison near La Spezia, where he was held in a sort of honorable imprisonment, and was compelled to undergo a tedious and painful operation for the healing of his wound. His venture had failed, but he was at least consoled by Europe's sympathy and continued interest. After being restored to health, he was released and allowed to return to Caprera.

In 1864 he visited London, where his presence was received with enthusiasm by the population.[16] He met the British prime minister Viscount Palmerston, as well as other revolutionaries then living in exile in the city. At that time, his ambitious international project included the liberation of a range of occupied nations, such as Croatia, Greece, Hungary.

第三次イタリア統一戦争

[編集]

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. The Austro-Prussian War had broken out, and Italy had allied with Prussia against Austria-Hungary in the hope of taking Venetia from Austrian rule (Third Italian War of Independence). Garibaldi gathered again his Hunters of the Alps, now some 40,000 strong, and led them into the Trentino. He defeated the Austrians at Bezzecca (thus securing the only Italian victory in that war) and made for Trento.

The Italian regular forces were defeated at Lissa on the sea, and made little progress on land after the disaster of Custoza. An armistice was signed, by which Austria ceded Venetia to Italy, but this result was largely due to Prussia's successes on the northern front. Garibaldi's advance through Trentino was for nought and he was ordered to stop his advance to Trento. Garibaldi answered with a short telegram from the main square of Bezzecca with the famous motto: Obbedisco! ("I obey!") .

普仏戦争とパリコミューン

[編集]After the war, Garibaldi led a political party that agitated for the capture of Rome, the peninsula's ancient capital. In 1867, he again marched on the city, but the Papal army, supported by a French auxiliary force, proved a match for his badly armed volunteers. He was shot and wounded in the leg in the Battle of Mentana, and had to withdraw out of the Papal territory. The Italian government again imprisoned and held him for some time, after which he again returned to Caprera.

In the same year, Garibaldi sought international support for altogether eliminating the papacy. At an 1867 congress in Geneva he proposed: "The papacy, being the most harmful of all secret societies, ought to be abolished."[17]

When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in July 1870, Italian public opinion heavily favored the Prussians, and many Italians attempted to sign up as volunteers at the Prussian embassy in Florence. After the French garrison was recalled from Rome, the Italian Army captured the Papal States without Garibaldi's assistance. Following the wartime collapse of the Second French Empire at the battle of Sedan, Garibaldi, undaunted by the recent hostility shown to him by the men of Napoleon III, switched his support to the newly declared French Third Republic. On 7 September 1870, within three days of the revolution of 4 September in Paris, he wrote to the Movimento of Genoa:

Yesterday I said to you: war to the death to Bonaparte. Today I say to you: rescue the French Republic by every means.[18]

Subsequently, Garibaldi went to France and assumed command of the Army of the Vosges, an army of volunteers.

病没

[編集]

Despite being elected again to the Italian parliament, Garibaldi spent much of his late years in Caprera. He however supported an ambitious project of land reclamation in the marshy areas of southern Lazio.

In 1879 he founded the "League of Democracy," which advocated universal suffrage, abolition of ecclesiastical property, emancipation of women, and maintenance of a standing army. Ill and confined to a bed by arthritis, he made trips to Calabria and Sicily. In 1880 he married Francesca Armosino, with whom he had previously had three children.

On his deathbed, Garibaldi asked that his bed be moved to where he could gaze at the emerald and sapphire sea. Upon his death on 2 June 1882 at the age of almost 75, his wishes for a simple funeral and cremation were not respected. He is buried on his farm on the island of Caprera alongside his last wife and some of his children.[19]

後世への影響

[編集]Garibaldi's popularity, his skill at rousing the common people, and his military exploits are all credited with making the unification of Italy possible. He also served as a global exemplar of mid-19th century revolutionary nationalism and liberalism. But following the liberation of southern Italy from the Neapolitan monarchy, Garibaldi chose to sacrifice his liberal republican principles for the sake of unification.

Garibaldi subscribed to the anti-clericalism common among Latin liberals, and did much to circumscribe the temporal power of the Papacy. His personal religious convictions are unclear to historians—in 1882 he wrote "Man created God, not God created Man," yet in his autobiography he is quoted as saying "I am a Christian, and I speak to Christians – I am a true Christian, and I speak to true Christians. I love and venerate the religion of Christ, because Christ came into the world to deliver humanity from slavery..." and "you have the duty to educate the people—educate the people—educate them to be Christians—educate them to be Italians... Viva Italia! Viva Christianity!"[20] The protestant minister Alessandro Gavazzi was his army chaplain.

An active Freemason, Garibaldi had little use for rituals, but thought of masonry as a network to unite progressive men as brothers both within nations and as members of a global community. He eventually was elected Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy.[21]

Giuseppe Garibaldi died at Caprera in 1882, where he was interred. Five ships of the Italian Navy have been named after him, among which a World War II cruiser and the former flagship, the aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Statues of his likeness, as well as the handshake of Teano, stand in many Italian squares, and in other countries around the world. On the top of the Janiculum hill in Rome, there is a statue of Garibaldi on horse-back. His face was originally turned in the direction of the Vatican (an allusion[要出典] to his ambition to conquer the Papal States), but after the Lateran Treaty in 1929 the orientation of the statue was changed upon request of the Vatican. A bust of Giuseppe Garibaldi is prominently placed outside the entrance to the old Supreme Court Chamber in the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, DC, a gift from members of the Italian Society of Washington. Many theatres in Sicily take their name from him and are named Garibaldi Theatre.

In a recent book review in The New Yorker ( 9 & 16 July 2007) of a Garibaldi biography, Tim Parks cites the eminent English historian, A.J.P. Taylor, as saying, "Garibaldi is the only wholly admirable figure in modern history."[1]

English football team Nottingham Forest designed their home kit after the uniform worn by Garibaldi and his men and have worn a variation of this design since being founded in 1865. A school in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire was also named after him. The Garibaldi biscuit was named after him, as was a style of beard. The Giuseppe Garibaldi Trophy has been awarded annually since 2007 within the Six Nations rugby union framework to the victory of the match between France and Italy, in the memory of Garibaldi.

Garibaldi, along with Giuseppe Mazzini and other Europeans supported the creation of a European federation. Many Europeans expected an unified Germany to become a European and world leader and to champion humanitarian policies. This is demonstrated in the following letter written by Giuseppe Garibaldi to Karl Blind on 10 April 1865.

The progress of humanity seems to have come to a halt, and you with your superior intelligence will know why. The reason is that the world lacks a nation which possesses true leadership. Such leadership, of course, is required not to dominate other peoples, but to lead them along the path of duty, to lead them toward the brotherhood of nations where all the barriers erected by egoism will be destroyed. We need the kind of leadership which, in the true tradition of medieval chivalry, would devote itself to redressing wrongs, supporting the weak, sacrificing momentary gains and material advantage for the much finer and more satisfying achievement of relieving the suffering of our fellow men. We need a nation courageous enough to give us a lead in this direction. It would rally to its cause all those who are suffering wrong or who aspire to a better life, and all those who are now enduring foreign oppression.

This role of world leadership, left vacant as things are today, might well be occupied by the German nation. You Germans, with your grave and philosophic character, might well be the ones who could win the confidence of others and guarantee the future stability of the international community. Let us hope, then, that you can use your energy to overcome your moth-eaten thirty tyrants of the various German states. Let us hope that in the center of Europe you can then make a unified nation out of your fifty millions. All the rest of us would eagerly and joyfully follow you.[22]

著作

[編集]この節の加筆が望まれています。 |

Garibaldi wrote at least two novels, characterized by an anti-clerical tone:

- Clelia or Il governo dei preti (1867) english translation, t. 1 english translation, t. 2

- Cantoni il volontario (1870)

- I Mille (1873)

He also wrote non-fiction:

- Autobiography[23] (v. 1 1807–1849)

- Memoirs,[24] co-authored by Alexandre Dumas

- A translation of his memoirs is The life of Garibaldi written by himself (New York: Barnes, 1859)

関連項目

[編集]人物

[編集]- Subhas Chandra Bose, a leader in the Indian independence movement who was influenced by Garibaldi and Mazzini.

- Raffaello Carboni

- Antoinette Henriette Clémence Robert

- Athanasios Diakos

- Giuseppe Garibaldi II

- Georgios Grivas

- Vittorio Emanuele II

- Jessie White Mario

出来事

[編集]記念碑

[編集]- Garibaldi Memorial

- Garibaldi Monument in Taganrog

- Monumento a Giuseppe Garibaldi

- Mount Garibaldi

- Garibaldi Secondary School

資料

[編集]出典

[編集]- ^ He is considered an Italian national hero Garibaldi, Giuseppe (1807-1882) - Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions

- ^ He is considered an Italian national hero Garibaldi, Giuseppe (1807-1882) - Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions

- ^ 『日本の目覚め』岡倉天心著

- ^ Baptismal record: "Die 11 d.i (giugno 1766) Dominicus Antonina Filius Angeli Garibaldi q. Dom.ci et Margaritae Filiae q. Antonij Pucchj Coniugum natus die 9 huius et hodie baptizatus fuit a me Curato Levantibus Io. Bapta Pucchio q. Antonij, et Maria uxore Agostini Dassi. (Chiavari, Archive of the Parish Church of S. Giovanni Battista, Baptismal Record, vol. n. 10 (dal 1757 al 1774), p. 174).

- ^ (often wrongly reported as Raimondi, but Status Animarum and Death Records all report the same name "Raimondo") Baptismal record from the Parish Church of S. Giovanni Battista in Loano: "1776, die vigesima octava Januarij. Ego Sebastianus Rocca praepositus hujus parrochialis Ecclesiae S[anct]i Joannis Baptistae praesentis loci Lodani, baptizavi infantem natam ex Josepho Raimimdi q. Bartholomei, de Cogoleto, incola Lodani, et [Maria] Magdalena Conti conjugibus, cui impositum est nomen Rosa Maria Nicolecta: patrini fuerunt D. Nicolaus Borro q. Benedicti de Petra et Angela Conti Joannis Baptistae de Alessio, incola Lodani." " Il trafugamento di Giuseppe Garibaldi dalla pineta di Ravenna a Modigliana ed in Liguria, 1849, di Giovanni Mini, Vicenza 1907 – Stab. Tip. L. Fabris.

- ^ A. Werner, Autobiography of Giuseppe Garibaldi, Vol. III, Howard Fertig, New York (1971) p. 68.

- ^ G. M. Trevelyan,Garibaldi's Defence of the Roman Republic, Longmans, London (1907) p. 227

- ^ a b c d e f g Garibaldi, Giuseppe (1889). Autobiography of Giuseppe Garibaldi. Walter Smith and Innes. pp. 54–69

- ^ a b Jackson, Kenneth T. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. The New York Historical Society and Yale University Press. p. 451

- ^ Bell, David. Ships, Strikes and Keelmen: Glimpses of North-Eastern Social History, 2001 ISBN 1-901237-26-5

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher. Garibaldi and His Enemies. New York: Penguin Books, 1987. p.171

- ^ Mack Smith, pp. 69–70

- ^ Mack Smith, p. 70

- ^ Carroll, Rory (8 February 2000). “Garibaldi asked by Lincoln to run army”. The Guardian (Guardian News and Media Limited) 3 June 2008閲覧。

- ^ Mack Smith, p. 72

- ^ Diamond, Michael (2003). Victorian Sensation. Anthem Press. pp. 50–53. ISBN 1-84331-150-X

- ^ Giuseppe Guerzoni, Garibaldi: con documenti editi e inediti, Florence, 1882, Vol. 11, 485.

- ^ Ridley, p. 602

- ^ Ridley, p. 633

- ^ Sinistra costituzionale, correnti democratiche e società italiana dal 1870 al 1892: atti del XXVII Convegno storico toscano (Livorno, 23–25 settembre 1984). L.S. Olschki. (1988). ISBN 978-88-222-3609-8 21 February 2011閲覧。

- ^ Garibaldi – the mason Translated from Giuseppe Garibaldi Massone by the Grand Orient of Italy

- ^ Denis Mack Smith (Editor), Garibaldi (Great Lives Observed), Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J. (1969) p. 76

- ^ Garibaldi, Giuseppe (1889). Autobiography

- ^ Garibaldi, Giuseppe; Alexandre Dumas, père (1861). The Memoirs of Garibaldi

書籍

[編集]- Hughes-Hallett, Lucy (2004). Heroes: A History of Hero Worship. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4399-9

- Young People's History of the World for the Past One Hundred Years. (1902)

- Ridley, Jasper (1976). Garibaldi. New York: Viking Press

- Mack Smith, Denis (1969). Garibaldi (Great Lives Observed). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall

- Werner, A. (1971). Autobiography of Giuseppe Garibaldi Vol. I, II, III. New York: Howard Fertig

- G.M. Trevelyan, Garibaldi's Defence of the Roman Republic and Garibaldi and the Thousand

- Garibaldi, Giuseppe; Dumas, Alexandre (1861). Garibaldi: an autobiography. Routledge

外部リンク

[編集]- Giuseppe Garibaldiの作品 (インターフェイスは英語)- プロジェクト・グーテンベルク

- Garibaldi & the Risorgimento – Brown University

- Brown University Library Original water-color panorama 273 ft in long painted around 1860 depicting the life and campaigns of Garibaldi

- The Giuseppe Garibaldi Foundation

- 1867 Caricature of Garibaldi by André Gill

- i Mille Garibaldini

- il Patriota dei Mille: Paolo Bovi Campeggi

- Review of Lucy Riall's Garibaldi: The Invention of a Hero

- "Mio Padre" by Clelia Garibaldi Book's web site

- the most beautiful walk in the world named after Anita Garibaldi Genoa Italy

- "That bronze of Garibaldi in New York Village …a long story", by Tiziano Thomas Dossena, bridgepugliausa.it, 2012