利用者:Talking1009/sandbox

|

ここはTalking1009さんの利用者サンドボックスです。編集を試したり下書きを置いておいたりするための場所であり、百科事典の記事ではありません。ただし、公開の場ですので、許諾されていない文章の転載はご遠慮ください。

登録利用者は自分用の利用者サンドボックスを作成できます(サンドボックスを作成する、解説)。 その他のサンドボックス: 共用サンドボックス | モジュールサンドボックス 記事がある程度できあがったら、編集方針を確認して、新規ページを作成しましょう。 |

ロバート・フラッド | |

|---|---|

| |

| 生誕 |

1574年1月17日 Milgate House, Bearsted, Kent |

| 死没 |

1637年9月8日(63歳没) ロンドン |

| 国籍 | 英国 |

| 職業 | 医師, 天文学者 |

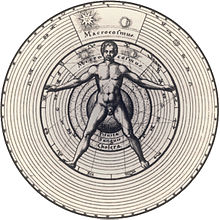

ロバート・フラッド(Robert Fludd、1574年1月17日 - 1637年9月8日)は、ルネサンス終期のイギリスの医師。当時主流ではなかったパラケルススの考えを中心に医学を学び、科学だけでなくオカルトにも興味を示した。音楽家、天文学者、数学者という側面を持ち、オカルトに関してはカバラを学び、薔薇十字団を支持した。

マクロコスモスとミクロコスモスの図などに代表されるように、フラッドは宇宙や自然の創生に関して、オカルト的な立場をとった。その考えに対してヨハネス・ケプラーが反論したことでも知られる[1]。

出自

[編集]フラッドは、イギリスのケントにあるベアーステッドのミルゲイトハウスで1574年に生まれた[2]。父はトーマス・フラッド。トーマスは高階級で、政府の要人であり、エリザベス1世の、ヨーロッパにおける戦争の財務担当をし、議会のメンバーを務めた[3]。フラッドの母はエリザベス・アンドレス・フラッド[4]。肖像画の右肩に書かれているのはフラッドの父系の家系の紋章である。彼の父系は、リリッド・フライド(Rhirid Flaidd)まで遡ることができ、"Fladd"という名字は「血まみれの(赤い)狼」を意味するウェールズ語が由来となる[5]。

医師になるまで

[編集]1591年にオックスフォード大学のセント・ジョンズ・カレッジに入学し、1597年に学位(B.A.)を取得、1598年には修士(M.A.)を取得した[2]。セント・ジョンズ・カレッジは、当時のイングランドにおいて医学のフェローシップを提供していた少ない機関のひとつであった。ウィリアム・ハフマンによれば、同カレッジにおけるメディカルフェローの存在が、フラッドにとって医学を勉強するきっかけとなったと語っている[2]。

1591年から1598年の間、フラッドのセント・ジョンズ・カレッジに在学中、研修医のメディカルフェローの一人はマシュー・グウィンであった。グウィンは、自身の著作において、ガレノスの医学に携わる一方で、パラケルススの医学知見にも詳しかったことを示唆していた。フラッドはオックスフォード時代に、グウィンやその著作に触れた可能性があり、それがフラッドが後に主張することになる、医学に関する考え方とその診察への採用にさらなる影響を与えたとされる。

育ちが良い紳士の教育のひとつに、外国を見て旅行するべきであるという考えがあった。フラッドはその考えにならい、セント・ジョンズ・カレッジを卒業後、1598年から1604年の間、ヨーロッパ本土を旅行した。彼がヨーロッパのどこに行っていたかは詳細に知られていないが[6]、まずはフランス、その後スペイン、イタリア、ドイツも訪れたとしている。彼自身の説明では、ピレネー山脈で冬を過ごし、イエスズ会の信者とともに theurgy(the practice of rituals)を学んだとのこと[7]。また、そのなかで医学、薬学、神秘思想のヘルメス主義を学んだ。

1604年にイングランドに戻ると、医学の学位を取ることを目的とし、オックスフォード大学のクライストチャーチに入学した。当時のクライストチャーチでは、医学の学位を取得する要件には、要求された医学の著作(主にガレノスとヒポクラテスによるもの) を読み、理解することがあった。フラッドはこれらのテキストに従って3つ論文を書き、1605年の5月14日、学位を認可された。同年の5月16日、医学士(M.B)と医師(M.D)の学位を取得してクライストチャーチを卒業した。

英国王立内科医協会での役割

[編集]卒業後、ロンドンへと引っ越し、フェンチャーチ・ストリートに住居をかまえ、英国王立内科医協会英国王立内科医協会に入るための試験を複数回受けたのち、1609年の9月に入会を許可された。試験官によって幾度も門前払いを受けた原因は、フラッドが当時主流ではなかったパラケルススの考え方を採用し、特にガレノスのような伝統的な医学の権威の考え方を用いるのに難色を示したことであった。最低6回は不合格になったとされる。

ロンドンの裕福な医師になり、協会の監査(Censor)を4回務めた(1618年、1627年、1633年、1634年)[2]。1614年に協会で行われたロンドンの薬剤師の監査にも参加し、1618年には王立内科医協会による標準的な調剤に関するテキストであるPharmacopoeia Londinensis の著作に携わった。彼は協会において認められた存在になり、協会では17世紀の 評論家たちに数えられた(ニコラス・カルペッパー とPeter Colesによる?)。

それに次いで、協会における彼の経歴と立場はさらに良い方向へと向かった。彼はウィリアム・パディと仲が良かった[6]。また、フラッドは協会のメンバーであるウィリアム・ハーベーの血液循環説を文字として初めて支持した人物の一人である[8]。しかし、フラッドがどの程度ハーベーの説に影響を与えたかは定かではない[9]。「循環」という用語は当時、曖昧さを含むものであった[10]。

オカルトへの興味

[編集]フラッドは、医学の考え方を、ガレノスのような当時主流であった古代の権威的人物ではなく、パラケルススの医学に従った。その一方で、彼は本来の知恵は自然魔術を使える者(natural magicians)の著作に見いだされるはずだ、ということを信じていた。こうした超常的な権威へのフラッドの考え方は偉大な数学者へも傾倒していった。その一例がピタゴラスやその支持者であり、フラッドは「数字によって大いなる秘密へアクセスすることができ、宗教における必然性は、数と割合を研究するとによってのみ発見される。」と信じていた。この考えは、ヨハネス・ケプラーとの論争を生んだ。

Mystical theory of nature

[編集]Tripartite division of matter 物質の三分割性

[編集]フラッドの著作や病理学に関する記述の多くは、人間、(四元素の)土、神の間のnatureの共感に見いだされるということを中心としていた。natureとしてはパラケルスス主義であったが、全てのものごとの起源に関するフラッド自身の理論では、トリア・プリマ(Tria Prima)とは異なり、すべての物事は最初の、暗い混沌(dark Chaos)から始まり、神の光がその混沌にあたることによって、ついに(四元素の)水をもたらした、というものである。フラッドは、この元素「水」を、神の精霊(the Spirit of the Lord)ともよび、全ての二次的な元素(secondary elements)と古典的な四元素それぞれの性質を含む、他の全ての物質の不活性物質を構成しているとした。さらに、フラッドは、自身の三分割性理論で、混沌と神の光によって、水と神の精霊のバリエーションが生まれ、パラケルススの(錬金術の)主要3原理(硫黄、塩、水銀)も生まれたと結論づけている。

The Trinitarian division is important in that it reflects a mystical framework for biology. Fludd was heavily reliant on scripture; in the Bible, the number three represented the principium formarum, or the original form. Furthermore, it was the number of the Holy Trinity. Thus, the number three formed the perfect body, paralleling the Trinity. This allowed man and earth to approach the infinity of God, and created a universality in sympathy and composition between all things.

Trinitarian divisionは、生物学に対してmystical な枠組みを反映させているという点で重要である。フラッドは聖書を頻繁に引用した。聖書において、「3」という数字はprincipum formarum(最初の形)を表していた。さらに、三位一体にに現れる数字でもある。ゆえに、「3」という数字は完全な身体を形成し、Trinity にparallelする。これによって、人間と土(earth)が神(God)の完全性に近づくことができ、森羅万象におけるsympathyとcompositionのuniversalityをつくった、ということである。

マクロコスムとミクロコスムの関係

[編集]Fludd's application of his mystically inclined tripartite theory to his philosophies of medicine and science was best illustrated through his conception of the Macrocosm and microcosm relationship. The divine light (the second of Fludd's primary principles) was the "active agent" responsible for creation. This informed the development of the world and the sun, respectively. Fludd concluded, from a reading of Psalm 19:4—"In them hath he set a tabernacle for the sun"—that the Spirit of the Lord was contained literally within the sun, placing it central to Fludd's model of the macrocosm.[11] remained in manuscript.[12] As the sun was to the earth, so was the heart to mankind. The sun conveyed Spirit to the earth through its rays, which circulated in and about the earth giving it life. Likewise, the blood of man carried the Spirit of the Lord (the same Spirit provided by the sun), and circulated through the body of man. This was an application of the sympathies and parallels provided to all of God's Creation by Fludd's tripartite theory of matter.

〜は、マクロコスモスとミクロコスモスの関係という彼の考えによって best illustrated.神の光(the divine light、フラッドの主なprinciplesの2番め)は創造を担うactive agentであった。これは世界と太陽の発達をそれぞれinformした。フラッドは、Psalm 19:4 「In them hath he set a tavernacle for the sun」を読んで、キリスト(the Lord)の魂(the Spirit)は、文字通り太陽の中に含まれており、フラッドのmacrocosmのモデルの中心となっていた。remained in manuscript. As the sun was to the earth, so was the heart to mankind. 太陽はその光を通してthe earthへと精霊を運び、which circulated in and about the earth giving it life.同様に、人間の血液はキリストの魂(太陽によって供給され るものと同じ精霊を指す)を運んでおり、人間の身体を循環しているとのことである。これは、神が創造した万物sympathiesとparallelsへの、フラッドの物質に対する三位一体理論の応用であった。

The blood was central to Fludd's conception of the relationship between the microcosm and macrocosm; the blood and the Spirit it circulated interacted directly with the Spirit conveyed to the macrocosm. The macrocosmal Spirit, carried by the Sun, was influenced by astral bodies and changed in composition through such influence. Comparatively, the astral influences on the macrocosmal Spirit could be transported to the microcosmal Spirit in the blood by the active commerce assumed between the macrocosm and the microcosm. Fludd extended this interaction to his conception of disease: the movement of Spirit between the macrocosm and microcosm could be corrupted and invade the microcosm as disease. Like Paracelsus, Fludd conceived of disease as an external invader, rather than a complexional imbalance.

血液は、ミクロコスムとマクロコスムの間の関係に関する、フラッドの考えの中心にあった。つまり、血液と精霊が循環し、それらはmacrososmへと運ばれる精霊と直接相互作用するというものである。太陽によって運ばれる、macrocosmal 精霊は、astral bodiesによって影響を受け、そのような影響を通して形を変える。それに比べて、macrocosmal Spiritに対するastral influence

死

[編集]1637年9月8日、ロンドンで人生を終えた。ベアーステッドのホーリークロス協会に埋葬された。

論争を生んだ作品や著作

[編集]

フラッドの作品は多くは議論を生んだ。彼はリアンドレアス・リバヴィウスに反対して薔薇十字団を支持し、ケプラーと議論を交わし、ピエール・ガッサンディなどのフランスの自然哲学者と論争し、武器軟膏を支持した[13]。

薔薇十字団の擁護

[編集]フラッドは薔薇十字団のメンバーではなかったとされているが、彼の多くの著作(manifestos and pamphlets)において十字団の考えを擁護した[14]。

例えば、リアンドレアス・リバヴィウスは、1615年の彼の著作Analysis confessions Fraternitatis de Rosea Cruce(薔薇十字の懺悔の分析)の中で、薔薇十字団は宗教的異端、 diabolical magic, sedition に甘んじていると主張していた。それに対し、フラッドはバヴィウスに反論するため、 Apologi Comendiariaという短い著作をまとめた。

Fludd returned to the subject at greater length, the following year.[2]

- Apologia Compendiaria, Fraternitatem de Rosea Cruce suspicionis … maculis aspersam, veritatis quasi Fluctibus abluens, &c., Leyden, 1616. Against Libavius.

- Tractatus Apologeticus integritatem Societatis de Rosea Cruce defendens, &c., Leyden, 1617.

- Tractatus Theologo-philosophicus, &c., Oppenheim, 1617. The date is given in a chronogram. This treatise "a Rudolfo Otreb Britanno" (where Rudolf Otreb is an anagram of Robert Floud) is dedicated to the Rosicrucian Fraternity. It consists of three books, De Vita, De Morte, and De Resurrectione. In the third book Fludd contends that those filled with the spirit of Christ may rise before his second coming.[13]

It is now seriously doubted that any formal organisation identifiable as the "Brothers of the Rose Cross" (Rosicrucians) ever actually existed in any extant form. The theological and philosophical claims circulating under this name appear, to these outsiders, to have been more an intellectual fashion that swept Europe at the time of the Counter Reformation. These thinkers suppose that in claiming to be part of a secret cult, scholars of alchemy, the occult, and Hermetic mysticism, merely sought that additional prestige by being able to promote their views while claiming exclusive adherence to some revolutionary pan-European secret society. By this logic, some suppose the society itself to never have existed.[要出典]

Between 1607 and 1616, two anonymous Rosicrucian manifestos were published by some anonymous person or group, first in Germany and later throughout Europe. These were the Fama Fraternitatis, (The Fame of the Brotherhood of RC), and the Confessio Fraternitatis, (The Confession of the Brotherhood of RC). The first manifesto was influenced by the work of the respected hermetic philosopher Heinrich Khunrath, of Hamburg, author of the Amphitheatrum Sapientiae Aeternae (1609) who himself had borrowed generously from the work of John Dee. It referred favourably to the role played by the Illuminati and it featured a convoluted manufactured history dating back to archaic mysteries of the Middle East, with references to the Kabala and the Persian Magi.

The second manifesto had decidedly anti-Catholic views which were popular at the time of the Counter Reformation. These manifestos were re-issued several times, and were both supported and countered by numerous pamphlets from anonymous authors: about 400 manuscripts and books were published on the subject between 1614 and 1620. The peak of the "Rosicrucianism furore" came in 1622 with mysterious posters appearing on the walls of Paris, and occult philosophers such as Michael Maier, Robert Fludd and Thomas Vaughan interested themselves in the Rosicrucian world view. Others intellectuals and authors later claimed to have published Rosicrucian documents in order to ridicule their views. The furore faded out and the Rosicrucians disappeared from public life until 1710 when the secret cult appears to have been revived as a formal organisation.

It is claimed that the work of John Amos Comenius and Samuel Hartlib on early education in England were strongly influenced by Rosicrucian ideas, but this has not been proven, and it appears unlikely except in the similarity in their anti-Catholic views and emphasis on science education. Rosicrucianism is also said to have been influential at the time when operative Masonry (a guild of artisans) was being transformed to speculative masonry—Freemasonry—which was a social fraternity, that also originally promoted the scientific and educative view of Comenius, Hartlib, Isaac Newton and Francis Bacon.

Rosicrucian literature became the sandbox of theosophists, and charlatans, who claimed to be connected with the mysterious Brotherhood. Robert Fludd led the battle. It is said by some that he was "the great English mystical philosopher of the seventeenth century, a man of immense erudition, of exalted mind, and, to judge by his writings, of extreme personal sanctity".[15]

It has also been said that what Fludd did was to liberate occultism, both from traditional Aristotelian philosophy, and from the coming (Cartesian) philosophy of his time.[16]

Against Kepler

[編集]Johannes Kepler criticised Fludd's theory of cosmic harmony in an appendix to his Harmonice Mundi (1619).[17]

- Veritatis Proscenium Frankfort, 1621. Reply to Kepler. In it Fludd argued from a Platonist point of view; and he claims that the hermetic or "chemical" approach is deeper than the mathematical.[18]

- Monochordon Mundi Symphoniacum Frankfort, 1622. Reply to Kepler's Mathematice, 1622.

- Anatomiæ Amphitheatrum, Frankfort, 1623. Includes reprint of the Monochordon.[13]

ヨハネス・ケプラーは、フラッドのcosmic harmony理論を、1619年の著作(Harmonice Mundi)で批判した。

Against the natural philosophers

[編集]

Brian Copenhaverによると、「ケプラーはtheosophistであるフラッドを非難し、ケプラーが正しかった」。

According to Brian Copenhaver, "Kepler accused Fludd of being a theosophist, and Kepler was right". Fludd was well-read in the tradition coming through Francesco Giorgi.[19] Marin Mersenne attacked him in Quæstiones Celebres in Genesim (1623).

- Sophiæ cum Moria Certamen, Frankfort, 1629. Reply to Mersenne.

- Summum Bonum, Frankfort, 1629. Under the name Joachim Frizius, this was a further reply to Mersenne, who had accused Fludd of magic.[13]

Pierre Gassendi took up the controversy in an Examen Philosophiæ Fluddanæ (1630). This was at Mersenne's request. Gassendi attacked Fludd's neo-Platonic position. He rejected the syncretic move that placed alchemy, cabbala and Christian religion on the same footing; and Fludd's anima mundi. Further he dismissed Fludd's biblical exegesis.[13][20]

Fludd also wrote against The Tillage of Light (1623) of Patrick Scot; Scot like Mersenne found the large claims of hermetic alchemy to be objectionable.[21] Fludd defended alchemy against the criticisms of Scot, who took it to be merely allegorical. This work, Truth's Golden Harrow,[11] remained in manuscript.[12]

武器軟膏

[編集]- "Doctor Fludds Answer vnto M. Foster, or, The Sqvesing of Parson Fosters Sponge", &c., London, 1631, (defence of weapon-salve, against the Hoplocrisma-Spongus, 1631, of William Foster, of Hedgerley, Buckinghamshire); an edition in Latin, "Responsum ad Hoplocrisma-Spongum", &c., Gouda, 1638.[13]

The idea that certain parallel actions could be initiated and linked by 'sympathetic' mysterious forces was widespread at this time, probably arising mainly from the actions of the magnet, shown by William Gilbert to always point towards some point in the northern sky. The idea owed a lot of the older Aristotelian and neo-Platonic views about soul-like forces.

Cosmology and other works

[編集]

Fludd's philosophy is presented in Utriusque Cosmi, Maioris scilicet et Minoris, metaphysica, physica, atque technica Historia (The metaphysical, physical, and technical history of the two worlds, namely the greater and the lesser, published in Germany between 1617 and 1621);[22] according to Frances Yates, his memory system (which she describes in detail in The Art of Memory, pp. 321–341) may reflect the layout of Shakespeare's Globe Theatre (The Art of Memory, Chapter XVI).

In 1618, Fludd wrote De Musica Mundana (Mundane Music) which described his theories of music, including his mundane (also known as "divine" or "celestial") monochord.[23]

In 1630, Fludd proposed many perpetual motion machines. People were trying to patent variations of Fludd's machine in the 1870s. Fludd's machine worked by recirculation by means of a water wheel and Archimedean screw. The device pumps the water back into its own supply tank.[24][25]

His main works are:[13]

- Utriusque Cosmi ... metaphysica, physica atque technica Historia, &c., Oppenheim and Frankfort, 1617–24. (It has two dedications, first to the Deity, secondly to James I, and copperplates; it was to have been in two volumes, the first containing two treatises, the second three; it was completed as far as the first section of the second treatise of the second volume.)

- Philosophia Sacra et vere Christiana, &c., Frankfort, 1626; dedicated to John Williams.

- Medicina Catholica, &c., Frankfort, 1629–31, in five parts; the plan included a second volume, not published.

Posthumous were:[13]

- Philosophia Moysaica, &c., Gouda, 1638; an edition in English, Mosaicall Philosophy, &c., London, 1659.

- Religio Exculpata, &c. [Ratisbon], 1684 (Autore Alitophilo Religionis fluctibus dudum immerso, tandem … emerso; preface signed J. N. J.; assigned to Fludd).

- Tractatus de Geomantia, &c. (four books), included in Fasciculus Geomanticus, &c., Verona, 1687.

An unpublished manuscript, copied by an amanuensis, and headed Declaratio breuis, &c., is in the Royal manuscripts, British Library, 12 C. ii. Fludd's Opera consist of his folios, not reprinted, but collected and arranged in six volumes in 1638; appended is a Clavis Philosophiæ et Alchimiæ Fluddanæ, Frankfort, 1633.[13]

Reception

[編集]William T. Walker, reviewing two books on Fludd in The Sixteenth Century Journal (by Joscelyn Godwin, and William Huffman), writes that "Fludd relied on the Bible, the Cabbala, and the traditions of alchemy and astrology. Many of his contemporaries labelled Fludd a magician and condemned him for his sympathy for the occult."[27] He cites Godwin's book as arguing that Fludd was part of the tradition of Christian esotericism that includes Origen and Meister Eckhart. He finds convincing the argument in Huffman's book that Fludd was not a Rosicrucian but was "a leading advocate of Renaissance Christian Neo-Platonism. Fludd's advocacy of an intellectual philosophy in decline has done much to assure his general neglect."[27]

Notes

[編集]- ^ Wolfgang Pauli, Wolfgang Pauli – Writings on physics and philosophy, translated by Robert Schlapp and edited by P. Enz and Karl von Meyenn (Springer Verlag, Berlin, 1994), Section 21, The influence of archetypical ideas on the scientific theories of Kepler. ISBN 3-540-56859-X, ISBN 978-3-540-56859-9.

- ^ a b c d e William H. Huffman (2001). Robert Fludd. North Atlantic Books. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-55643-373-3

- ^ Members Constituencies Parliaments Surveys. “historyofparliamentonline.org/ Fludd, Sir Thomas (d.1607), of Milgate, Kent”. Historyofparliamentonline.org. 2013年8月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Sir Thomas Fludd, Knight of, Milgate, Bearsted, Kent, England d. Yes, date unknown: Community Trees Project”. Histfam.familysearch.org. 20 December 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2013年8月17日閲覧。

- ^ https://www.ourfamtree.org/browse.php?pid=669162 OurFamTree.org

- ^ a b Debus pp. 207–8.

- ^ Urszula Szulakowska (2000). The Alchemy of Light: Geometry and Optics in Late Renaissance Alchemical Illustration. BRILL. p. 168. ISBN 978-90-04-11690-0

- ^ William H. Huffman (2001). Robert Fludd. North Atlantic Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-55643-373-3

- ^ Walter Pagel (1967). William Harvey's Biological Ideas: Selected Aspects and Historical Background. Karger Publishers. p. 340. ISBN 978-3-8055-0962-6

- ^ Allen G. Debus, Robert Fludd and the Circulation of the Blood, J Hist Med Allied Sci (1961) XVI (4): 374-393. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/XVI.4.374

- ^ a b William H. Huffman (2001). Robert Fludd. North Atlantic Books. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-55643-373-3

- ^ a b Debus, p. 255.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i . Dictionary of National Biography (英語). London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ William H. Huffman, Robert Fludd and the End of the Renaissance (Routledge London & New York, 1988)

- ^ The Real History of the Rosicrucians, by Arthur Edward Waite, [1887],

- ^ Daniel Garber; Michael Ayers (2003). The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. p. 457. ISBN 978-0-521-53720-9

- ^ Johannes Kepler; E. J. Aiton; Alistair Matheson Duncan; Judith Veronica Field (1997). The Harmony of the World. American Philosophical Society. p. xxxviii. ISBN 978-0-87169-209-2

- ^ William H. Huffman (1988). Robert Fludd and the End of the Renaissance. Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-415-00129-8

- ^ Daniel Garber; Michael Ayers (2003). The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 464–5. ISBN 978-0-521-53720-9

- ^ Antonio Clericuzio (2000). Elements, Principles and Corpuscles: A Study of Atomism and Chemistry in the Seventeenth Century. Springer. pp. 71–2. ISBN 978-0-7923-6782-6

- ^ Bruce Janacek (2012-06-19). Alchemical Belief: Occultism in the Religious Culture of Early Modern England. Penn State Press. pp. 45–54. ISBN 978-0-271-05014-0

- ^ Karsten Kenklies, Wissenschaft als Ethisches Programm. Robert Fludd und die Reform der Bildung im 17. Jahrhundert (Jena, 2005)

- ^ Manly P. Hall, The Secret Teachings of All Ages: An Encyclopedic outline of Masonic, Hermetic, Qabbalistic, and Rosicrucian symbolical philosophy (H.S. Crocker Company, Inc., 1928)

- ^ http://www.uh.edu/engines/pmm1.jpg Template:Bare URL image

- ^ http://www.windmillworld.com/mills/images/fludd1618.gif Template:Bare URL image

- ^ Joscelyn Godwin, Robert Fludd: Hermetic philosopher and surveyor of two worlds (1979), p. 70.

- ^ a b Walker, William T. (1992). “Robert Fludd and the End of the Renaissance. by William H. Huffman; Robert Fludd,Hermetic Philosopher and Surveyor of Two Worlds. by Joscelyn Godwin; Splendor Soils. bySalomon Trismosin; Joscelyn Godwin. Review”. The Sixteenth Century Journal 23 (1): 157–158. doi:10.2307/2542084. JSTOR 2542084.

References

[編集]- Allen G. Debus (2002), The Chemical Philosophy

Further reading

[編集]- Allen G. Debus, The English Paracelsians, New York: Watts, 1965.

- Tita French Baumlin, "Robert Fludd," The Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 281: British Rhetoricians and Logicians, 1500–1660, Second Series, Detroit: Gale, 2003, pp. 85–99.

- James Brown Craven, Doctor Fludd (Robertus de Fluctibus), the English Rosicrucian: Life and Writings, Kirkwall: William Peace & Son, 1902.

- Frances A. Yates, The Art of Memory, London: Routledge, 1966.

- William H. Huffman, ed., Robert Fludd: Essential Readings, London: Aquarian/Thorsons, 1992.

- Johannes Rösche, Robert Fludd. Der Versuch einer hermetischen Alternative zur neuzeitlichen Naturwissenschaft (Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008).

- Karsten Kenklies, Wissenschaft als Ethisches Programm. Robert Fludd und die Reform der Bildung im 17. Jahrhundert (Jena, 2005).

External links

[編集]- Guariento, Luca (2016) Life, Friends, and Associations of Robert Fludd: A Revised Account

- Robert Fludd biography at Levity

- Fludd's magnum opus, 'Utriusque Cosmi maioris salicet et minoris metaphysica..' (1617–1619) is available as ZIP or PDF download.

- A large section of 'Utriusque Cosmi maioris salicet et minoris metaphysica..' is available as page images at the University of Utah.

- JR Ritman Library: Treasures from the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica

- Robert Fludd chronology

- Utriusque Cosmi maioris salicet et minoris metaphysica (1617) at the Internet Archive

- Article by Urszula Szulakowska on the religious imagery of Utriusque Cosmi, including gallery and links to online public domain copies.

- Hutchinson, John (1892). “Robert Flood”. Men of Kent and Kentishmen (Subscription ed.). Canterbury: Cross & Jackman. p. 50

- 1574 births

- 1637 deaths

- 16th-century astrologers

- 16th-century English mathematicians

- 16th-century English writers

- 16th-century male writers

- 16th-century occultists

- 17th-century astrologers

- 17th-century English mathematicians

- 17th-century English medical doctors

- 17th-century English writers

- 17th-century English male writers

- 17th-century occultists

- Alumni of St John's College, Oxford

- English Anglicans

- English astrologers

- English music theorists

- English occult writers

- Hermeticists

- Mystics

- Paracelsians

- People from Bearsted

- Hermetic Qabalists

- Rosicrucians