L型菌

L型菌(L-form bacteria)は、細胞壁を持たない細菌の株である[1]。エミー・クラインバーガー=ノーベルが1935年に初めて単離し、勤めていたロンドンのリスター研究所に因んでL型菌と名付けた[2]。

分裂能を持つスフェロプラストであるが元の形態に戻ることもできる不安定型と、元の細菌には戻ることのできない安定型の2種類に分類できる。

マイコプラズマのような寄生種の一部にも細胞壁を欠くものがあるが[3]、細胞壁を持つ細菌に由来しないため、L型菌とは見なされない[4]。

外観と細胞分裂

[編集]

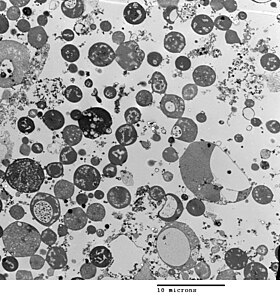

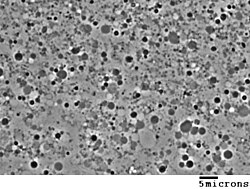

細菌の形態は、細胞壁によって決まる。L型菌は細胞壁を持たないため、その形態は、由来する細菌とは異なる。典型的なL型菌は、球型か回転楕円体型である。例えば、桿菌である枯草菌に由来するL型菌は、位相差顕微鏡や透過型電子顕微鏡で観察すると丸く見える[5]。

L型菌は、グラム陽性菌からもグラム陰性菌からも生じるが、グラム染色試験では、L型菌は細胞壁を持たないため、常にグラム陰性菌の色を示す。

細胞壁は細胞分裂にとって重要であり、大部分の細菌では、二分裂で分裂する。この過程は通常細胞壁及びFtsZ等の細胞骨格を必要とする。L型菌がこの両方の構造を持たずに成長や分裂を行うのは非常に独特で、初期の生命の細胞分裂の形態を表していると考えられている[1]。この分裂形態は、細胞表面から伸びている細い突起部と関連があるようであり、この突起部は新しい細胞をくびり切る。L型菌では細胞壁がないため、分裂は組織化されず乱雑であり、非常に小さいものから非常に大きいものまで、様々な大きさの細胞が生じる[1]。

培養中での発生

[編集]枯草菌や大腸菌等、通常は細胞壁を持つ多くの種から、抗生物質でペプチドグリカン生合成を阻害したり、細胞壁を消化するリゾチームで細胞を処理することにより、実験的にL型菌を生じさせることができる。L型菌は、浸透圧衝撃で細胞溶解を起こさないような、細菌の細胞質と同じ浸透圧の培地で発生する[2]。L型株は不安定で、細胞壁を再生して普通の細菌に戻りやすいが、これらを生成させたのと同じ環境で長い期間培養し続け、細胞壁の形成を不可能にする変異を蓄積させることで防ぐことができる[6]。

いくつかの研究では、突然変異が起こっていることが確認されている[1][2]。そのような点突然変異の1つは、脂質代謝のメバロン酸経路に関わる酵素(yqiD/ispA)の変異で、これによりL型菌の形成頻度が1000倍になる[1]。この効果が生じる理由は未知であるが、この酵素がペプチドグリカンの合成に重要な脂質を合成することと関連していると考えられている。

他の誘導方法としてはナノテクノロジーを利用したものがあり、極端な空間的束縛をかけるマイクロ流体デバイスが構築されている。サブミクロンスケールの通路を介して連結された微細環境からなる空間を拡散させるなどの方法で、L型菌に似た形状変化が選択される適応環境を設置することでL型菌に似た細胞が生じる[7][8]。

重要性と応用

[編集]いくつかの論文では、L型菌がヒト[9]やその他の動物[10]の病気の原因になることが指摘されているが、L型菌と病気を結びつける証拠はしばしば矛盾しており、この仮説については議論が続いている[11][12]。L型菌の研究は続いており、例えば実験的にNocardia caviaeを植菌した後のマウスの肺でも見つかっている[13][14]。最近の研究では、造血幹細胞移植を受け免疫抑制中の患者に感染することが示唆されている[15]。細胞壁を欠いた細菌株の形成は、抗生物質耐性を獲得する上で重要であるとする提案もある[16]。

L型菌は、初期の生命の研究やバイオテクノロジーにとって有用である。組換えタンパク質発現のホスト株として用いる研究もなされている[17][18][19]。その場合、通常はペリプラズムに蓄積してしまう分泌タンパク質を大量に生産することができる[20][21]。ペリプラズムへのタンパク質の蓄積は細菌にとって毒となり、発現タンパク質を減らすことになる。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c d e Leaver M, Domínguez-Cuevas P, Coxhead JM, Daniel RA, Errington J (February 2009). “Life without a wall or division machine in Bacillus subtilis”. Nature 457 (7231): 849–53. doi:10.1038/nature07742. PMID 19212404.

- ^ a b c Joseleau-Petit D, Liébart JC, Ayala JA, D'Ari R (September 2007). “Unstable Escherichia coli L Forms Revisited: Growth Requires Peptidoglycan Synthesis”. J. Bacteriol. 189 (18): 6512–20. doi:10.1128/JB.00273-07. PMC 2045188. PMID 17586646.

- ^ Razin S, Yogev D, Naot Y (December 1998). “Molecular Biology and Pathogenicity of Mycoplasmas”. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62 (4): 1094–156. PMC 98941. PMID 9841667.

- ^ Domingue GJ, Woody HB (April 1997). “Bacterial persistence and expression of disease”. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10 (2): 320–44. PMC 172922. PMID 9105757. Full PDF

- ^ Gilpin RW, Young FE, Chatterjee AN (January 1973). “Characterization of a Stable L-Form of Bacillus subtilis 168”. J. Bacteriol. 113 (1): 486–99. PMC 251652. PMID 4631836.

- ^ Allan EJ (April 1991). “Induction and cultivation of a stable L-form of Bacillus subtilis”. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 70 (4): 339–43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb02946.x. PMID 1905284.

- ^ Männik J.; R. Driessen; P. Galajda; J.E. Keymer; C. Dekker (September 2009). “Bacterial growth and motility in sub-micron constrictions”. PNAS 106 (35): 14861–14866. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..10614861M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907542106. PMC 2729279. PMID 19706420.

- ^ Keymer J.E.; P. Galajda; C. Muldoon R.; R. Austin (November 2006). “Bacterial metapopulations in nanofabricated landscapes”. PNAS 103 (46): 17290–295. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..10317290K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607971103. PMC 1635019. PMID 17090676.

- ^ Wall S, Kunze ZM, Saboor S, Soufleri I, Seechurn P, Chiodini R, McFadden JJ (1993). “Identification of spheroplast-like agents isolated from tissues of patients with Crohn's disease and control tissues by polymerase chain reaction”. J Clin Microbiol 31 (5): 1241–5. PMC 262911. PMID 8501224.

- ^ Hulten K, Karttunen TJ, El-Zimaity HM, Naser SA, Collins MT, Graham DY, El-Zaatari FA (2000). “Identification of cell wall deficient forms of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in paraffin embedded tissues from animals with Johne's disease by in situ hybridization”. J Microbiol Methods 42 (2): 185–95. doi:10.1016/S0167-7012(00)00185-8. PMID 11018275.

- ^ Onwuamaegbu ME, Belcher RA, Soare C (2005). “Cell wall-deficient bacteria as a cause of infections: a review of the clinical significance”. J. Int. Med. Res. 33 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1177/147323000503300101. PMID 15651712.

- ^ Casadesús J (December 2007). “Bacterial L-forms require peptidoglycan synthesis for cell division”. BioEssays 29 (12): 1189–91. doi:10.1002/bies.20680. PMID 18008373.

- ^ Beaman BL (July 1980). “Induction of L-phase variants of Nocardia caviae within intact murine lungs”. Infect. Immun. 29 (1): 244–51. PMC 551102. PMID 7399704.

- ^ Beaman BL, Scates SM (September 1981). “Role of L-forms of Nocardia caviae in the development of chronic mycetomas in normal and immunodeficient murine models”. Infect. Immun. 33 (3): 893–907. PMC 350795. PMID 7287189.

- ^ Woo PC, Wong SS, Lum PN, Hui WT, Yuen KY (March 2001). “Cell-wall-deficient bacteria and culture-negative febrile episodes in bone-marrow-transplant recipients”. Lancet 357 (9257): 675–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04131-3. PMID 11247551.

- ^ Fuller E, Elmer C, Nattress F, et al (December 2005). “β-Lactam Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus Cells That Do Not Require a Cell Wall for Integrity”. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49 (12): 5075–80. doi:10.1128/AAC.49.12.5075-5080.2005. PMC 1315936. PMID 16304175.

- ^ Sieben, Stefan. “Die stabilen Protoplasten-Typ L-Formen von Proteus mirabilis als neues Expressionssystem für sekretorische Proteine und integrale Mempranproteine”. Dissertation Universität Jena, April 1998, OCLC-Nummer: 246350676, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/246350676.

- ^ Sieben S, Hertle R, Gumpert J, Braun V. (October 1998). “The Serratia marcescens hemolysin is secreted but not activated by stable protoplast-type L-forms of Proteus mirabilis.”. Arch Microbiol. 170 (4): 236-42.. doi:10.1007/s002030050638. PMID 9732437.

- ^ Gumpert J, Hoischen C (October 1998). “Use of cell wall-less bacteria (L-forms) for efficient expression and secretion of heterologous gene products”. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 9 (5): 506–9. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(98)80037-2. PMID 9821280.

- ^ Rippmann JF, Klein M, Hoischen C, et al (1 December 1998). “Procaryotic Expression of Single-Chain Variable-Fragment (scFv) Antibodies: Secretion in L-Form Cells of Proteus mirabilis Leads to Active Product and Overcomes the Limitations of Periplasmic Expression in Escherichia coli”. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64 (12): 4862–9. PMC 90935. PMID 9835575.

- ^ Choi JH, Lee SY (June 2004). “Secretory and extracellular production of recombinant proteins using Escherichia coli”. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 64 (5): 625–35. doi:10.1007/s00253-004-1559-9. PMID 14966662.

関連文献

[編集]- Domingue, Gerald J. (1982). Cell wall-deficient bacteria: basic principles and clinical significance. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. ISBN 0-201-10162-9

- Mattman, Lida H. (2001). Cell wall deficient forms: stealth pathogens. Boca Raton: CRC. ISBN 0-8493-8767-1

関連項目

[編集]外部リンク

[編集]- Errington Group at Newcastle University

- Scientists explore new window on the origins of life 2009 Newcastle University press release