利用者:Appassionata3/sandbox

|

ここはAppassionata3さんの利用者サンドボックスです。編集を試したり下書きを置いておいたりするための場所であり、百科事典の記事ではありません。ただし、公開の場ですので、許諾されていない文章の転載はご遠慮ください。

登録利用者は自分用の利用者サンドボックスを作成できます(サンドボックスを作成する、解説)。 この利用者の下書き:User:Appassionata3/sandbox・User:Appassionata3/completion・User:Appassionata3/ポルトガル・User:Appassionata3/Shitagaki その他のサンドボックス: 共用サンドボックス | モジュールサンドボックス 記事がある程度できあがったら、編集方針を確認して、新規ページを作成しましょう。 |

デンマーク領エストニア

[編集]- エストニア公国

- Hertugdømmet Estland

Ducatus Estoniae -

1219年 - 1346年  →

→ →

→

(デンマークの国旗) (Seal of Valdemar IV of Denmark)

Territories that were part of the Kingdom of Denmark from 1219 to 1645-

公用語 デンマーク語、エストニア語、Low German 宗教 カトリック 首都 不明 - デンマーク国王

-

1219年 - 1241年 Valdemar II 1340年 - 1346年 Valdemar IV 1559年 - 1588年 Frederick II 1588年 - 1645年 Christian IV - 変遷

-

設立 1219年 リンダニスの戦い 1219年6月15日 タリンがハンザ同盟に加盟¹ 1248年 解体 1346年

現在  エストニア

エストニア

- 1 Wesenberg (Rakvere) was granted Lübeck city rights in 1302 by King Erik Menved. Narva received these rights in 1345.

エストニア公国[1](エストニアこうこく、デンマーク語: Hertugdømmet Estland[2]、ラテン語: Ducatus Estoniae[3])またはデンマーク領エストニアは、a direct dominion (ラテン語: dominium directum) of the King of Denmark from 1219 until 1346 when it was sold to the Teutonic Order and became part of the Ordensstaat.

Denmark rose as a great military and mercantile power in the 12th century. It had an interest in ending the frequent Estonian attacks that threatened its Baltic trade. Danish fleets attacked Estonia in 1170, 1194, and 1197. In 1206, King Valdemar II and archbishop Andreas Sunonis led a raid on Ösel island (Saaremaa). The Kings of Denmark claimed Estonia, and this was recognised by the pope. In 1219 the Danish fleet landed in the major harbor of Estonia and defeated the Estonians in the Battle of Lindanise that brought Northern Estonia under Danish rule until the Estonian uprising in 1343, when the territories were taken over by the Teutonic Order. They were sold by Denmark in 1346.

スペイン領ネーデルラント

[編集]- スペイン領ネーデルラント

- Spaanse Nederlanden

Países Bajos Españoles

Spanische Niederlande

Spuenesch Holland

Pays-Bas Espagnols

Belgica Regia -

←

1556年 - 1714年  →

→ →

→

(国旗) (国章) - 国の標語: Plus Ultra

更なる前進

1700年時のスペイン領ネーデルラントの地図(灰色)-

公用語 オランダ語、フランス語、ドイツ語、ラテン語、スペイン語、低ザクセン語、西フリジア語、ワロン語、ルクセンブルク語 国教 カトリック 宗教 プロテスタント 首都 ブリュッセル - 総督

-

1581年 - 1592年 アレッサンドロ・ファルネーゼ 1692年 - 1706年 マクシミリアン・エマヌエル - 人口

-

1700年[4] 1,794,000人 - 変遷

-

スペイン・ハプスブルク朝がハプスブルク領ネーデルラントを獲得 1556年 八十年戦争 1568年 - 1648年 Peace of Münster 1648年1月30日 再統合戦争 1683年 - 1684年 レーゲンスブルクの和約 1684年8月15日 アウクスブルク同盟戦争 1688年 - 1697年 スペイン継承戦争 1701年 - 1714年 ラシュタット条約 1714年3月7日

通貨 グルデン 現在  ベルギー

ベルギー ルクセンブルク

ルクセンブルク フランス

フランス ドイツ

ドイツ

| ネーデルラントの歴史 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| フリーシー族 | ベルガエ族 | |||||||

| カナネファテス族 | カマウィ族 トゥバンテス族 |

ガリア・ベルギカ (紀元前55年 - 5世紀ごろ) ゲルマニア・インフェリオル (83年 - 5世紀ごろ) | ||||||

| サリ・フランク族 | バタウィ族 | |||||||

| 無人 (4世紀 - 5世紀ごろ) |

ザクセン族 | サリ・フランク族 (4世紀 - 5世紀ごろ) |

||||||

| フリースラント王国 (6世紀ごろ - 734年) |

フランク王国(481年 - 843年) カロリング帝国 (800年 - 843年) | |||||||

| アウストラシア(511年 - 687年) | ||||||||

| 中部フランク王国(843年 - 855年) | 西フランク王国 (843年 - 987年) |

|||||||

| ロタリンギア王国(855年 - 959年) 下ロタリンギア公国(959年 - 1190年) |

||||||||

| フリースラント | ||||||||

フリースラントの自由 (11世紀 - 16世紀) |

ホラント伯国 (880年 - 1432年) |

ユトレヒト司教領 (695年 - 1456年) |

ブラバント公国 (1183年 - 1430年) ゲルデルン公国 (1046年 - 1543年) |

フランドル伯国 (862年 - 1384年) |

エノー伯国 (1071年 - 1432年) ナミュール伯国 (981年 - 1421年) |

リエージュ司教領 (980年 - 1794年) |

ルクセンブルク公国 (1059年 - 1443年) | |

ブルゴーニュ領ネーデルラント(1384年 - 1482年) |

||||||||

ハプスブルク領ネーデルラント(1482年 - 1795年) (ネーデルラント17州1543年以降) |

||||||||

ネーデルラント連邦共和国 (1581年 - 1795年) |

スペイン領ネーデルラント (1556年 - 1714年) |

|||||||

オーストリア領ネーデルラント (1714年 - 1795年) |

||||||||

ベルギー合衆国 (1790年) |

リエージュ共和国 (1789年 - 1791年) |

|||||||

バタヴィア共和国(1795年 - 1806年) ホラント王国(1806年 - 1810年) |

フランス第一共和政(1795年 - 1804年) フランス第一帝政(1804年 - 1815年) | |||||||

ネーデルラント連合公国(1813年 - 1815年) |

||||||||

| ネーデルラント連合王国(1815年 - 1830年) | ルクセンブルク 大公国 (同君連合、1815年 - ) | |||||||

オランダ王国(1839年 - ) |

ベルギー王国(1830年 - ) | |||||||

| ルクセンブルク大公国 (1890年 - ) | ||||||||

スペイン領ネーデルラント(スペインりょうネーデルラント、スペイン語: Países Bajos Españoles、オランダ語: Spaanse Nederlanden、フランス語: Pays-Bas espagnols、ドイツ語: Spanische Niederlande、歴史的にはスペイン語で Flandesと呼ぶ、"Flanders"という名前はused as a pars pro toto[5])は、ハプスブルク領ネーデルラントのうち、1556年から1714年までのスペイン・ハプスブルク家によって支配された時期を指す。They were a collection of States of the Holy Roman Empire in the Low Countries held in personal union by the Spanish Crown (also called Habsburg Spain).この地域は、現在のベルギーとルクセンブルクの大部分に加え、北フランス、南ドイツの一部で構成されており、首都はブリュッセルにおかれた。フランドル軍はこの地域の防衛を任せられた。

ブルゴーニュ領ネーデルラントの領地は、1482年のマリー・ド・ブルゴーニュの死後、断絶したヴァロワ=ブルゴーニュ家からオーストリア・ハプスブルク家が継承したものであった。17州はハプスブルク領ネーデルラントの中核をなし、1556年に皇帝カール5世が退位すると、スペイン・ハプスブルク家に譲渡された。1581年、ネーデルラントの一部が分離してネーデルラント連邦共和国が成立すると、残りの地域はスペイン継承戦争までスペインの支配下に置かれた。

歴史

[編集]背景

[編集]ブラバント公国を中心とするネーデルラント諸侯の共同統治は、フィリップ善良公の支配下で、オランダ総督の導入と1464年の第1回スターテン・ヘネラールによって既に行われていた[6]。His granddaughter Mary had confirmed a number of privileges to the States by the Great Privilege signed in 1477.[7] After the government takeover by her husband Archduke Maximilian I of Austria, the States insisted on their privileges, culminating in a Hook rebellion in Holland and Flemish revolts. Maximilian prevailed with the support of Duke Albert III of Saxony and his son Philip the Handsome, husband of Joanna of Castile, could assume the rule over the Habsburg Netherlands in 1493.

Philip as well as his son and successor Charles V retained the title of a "Duke of Burgundy" referring to their Burgundian inheritance, notably the Low Countries and the Free County of Burgundy in the Holy Roman Empire. The Habsburgs often used the term Burgundy to refer to their hereditary lands (e.g. in the name of the Imperial Burgundian Circle established in 1512), actually until 1795, when the Austrian Netherlands were lost to the French Republic. The Governor-general of the Netherlands was responsible for the administration of the Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries. Charles V was born and raised in the Low Countries and often stayed at the Palace of Coudenberg in Brussels.

By the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549, Charles V declared the Seventeen Provinces a united and indivisible Habsburg dominion. Between 1555 and 1556, the House of Habsburg split into an Austro-German and a Spanish branch as a consequence of Charles's abdications: the Netherlands were left to his son Philip II of Spain, while his brother Archduke Ferdinand I succeeded him as Holy Roman Emperor. The Seventeen Provinces, de jure still fiefs of the Holy Roman Empire, from that time on de facto were ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs as part of the Burgundian heritage.

Eighty Years' War

[編集]Philip's stern Counter-Reformation measures sparked the Dutch Revolt in the mainly Calvinist Netherlandish provinces, which led to the outbreak of the Eighty Years' War in 1568. In January 1579 the seven northern provinces formed the Protestant Union of Utrecht, which declared independence from the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands by the 1581 Act of Abjuration. The Spanish branch of the Habsburgs could retain the rule only over the partly Catholic Southern Netherlands, completed after the Fall of Antwerp in 1585.

Obv: Portraits of Albert and Isabella.

Rev: Eagle holding balance, date 1612.

Better times came, when in 1598 the Spanish Netherlands passed to Philip's daughter Isabella Clara Eugenia and her husband Archduke Albert VII of Austria. The couple's rule brought a period of much-needed peace and stability to the economy, which stimulated the growth of a separate South Netherlandish identity and consolidated the authority of the House of Habsburg reconciling previous anti-Spanish sentiments. In the early 17th century, there was a flourishing court at Brussels. Among the artists who emerged from the court of the "Archdukes", as they were known, was Peter Paul Rubens. Under Isabella and Albert, the Spanish Netherlands actually had formal independence from Spain, but always remained unofficially within the Spanish sphere of influence. With Albert's death in 1621 they returned to formal Spanish control, although the childless Isabella remained on as Governor until her death in 1633.

The failing wars intended to regain the 'heretical' northern Netherlands meant significant loss of (still mainly Catholic) territories in the north, which was consolidated in 1648 in the Peace of Westphalia, and given the peculiar inferior status of Generality Lands (jointly ruled by the United Republic, not admitted as member provinces): Zeelandic Flanders (south of the river Scheldt), the present Dutch province of North Brabant and Maastricht (in the present-day Dutch province of Limburg).

French conquests

[編集]As the power of the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs waned in the latter decades of the 17th century, the territory of the Netherlands under Habsburg rule was repeatedly invaded by the French and an increasing portion of the territory came under French control in successive wars. By the Treaty of the Pyrenees of 1659 the French annexed most of Artois, and Dunkirk was ceded to the English. By the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (ending the War of Devolution in 1668) and Nijmegen (ending the Franco-Dutch War in 1678), further territory up to the current Franco-Belgian border was ceded, including Cambrai, Walloon Flanders, as well as half of the county of Hainaut (including Valenciennes). Later, in the War of the Reunions and the Nine Years' War, France annexed other parts of the region that were restored to Spain by the Treaty of Rijswijk 1697.

During the War of the Spanish Succession, in 1706 the Habsburg Netherlands became an Anglo-Dutch condominium for the remainder of the conflict.[8] By the peace treaties of Utrecht and Rastatt in 1713/14 ending the war, the Southern Netherlands returned to the Austrian Habsburg monarchy forming the Austrian Netherlands.

| ネーデルラントの歴史 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| フリーシー族 | ベルガエ族 | |||||||

| カナネファテス族 | カマウィ族 トゥバンテス族 |

ガリア・ベルギカ (紀元前55年 - 5世紀ごろ) ゲルマニア・インフェリオル (83年 - 5世紀ごろ) | ||||||

| サリ・フランク族 | バタウィ族 | |||||||

| 無人 (4世紀 - 5世紀ごろ) |

ザクセン族 | サリ・フランク族 (4世紀 - 5世紀ごろ) |

||||||

| フリースラント王国 (6世紀ごろ - 734年) |

フランク王国(481年 - 843年) カロリング帝国 (800年 - 843年) | |||||||

| アウストラシア(511年 - 687年) | ||||||||

| 中部フランク王国(843年 - 855年) | 西フランク王国 (843年 - 987年) |

|||||||

| ロタリンギア王国(855年 - 959年) 下ロタリンギア公国(959年 - 1190年) |

||||||||

| フリースラント | ||||||||

フリースラントの自由 (11世紀 - 16世紀) |

ホラント伯国 (880年 - 1432年) |

ユトレヒト司教領 (695年 - 1456年) |

ブラバント公国 (1183年 - 1430年) ゲルデルン公国 (1046年 - 1543年) |

フランドル伯国 (862年 - 1384年) |

エノー伯国 (1071年 - 1432年) ナミュール伯国 (981年 - 1421年) |

リエージュ司教領 (980年 - 1794年) |

ルクセンブルク公国 (1059年 - 1443年) | |

ブルゴーニュ領ネーデルラント(1384年 - 1482年) |

||||||||

ハプスブルク領ネーデルラント(1482年 - 1795年) (ネーデルラント17州1543年以降) |

||||||||

ネーデルラント連邦共和国 (1581年 - 1795年) |

スペイン領ネーデルラント (1556年 - 1714年) |

|||||||

オーストリア領ネーデルラント (1714年 - 1795年) |

||||||||

ベルギー合衆国 (1790年) |

リエージュ共和国 (1789年 - 1791年) |

|||||||

バタヴィア共和国(1795年 - 1806年) ホラント王国(1806年 - 1810年) |

フランス第一共和政(1795年 - 1804年) フランス第一帝政(1804年 - 1815年) | |||||||

ネーデルラント連合公国(1813年 - 1815年) |

||||||||

| ネーデルラント連合王国(1815年 - 1830年) | ルクセンブルク 大公国 (同君連合、1815年 - ) | |||||||

オランダ王国(1839年 - ) |

ベルギー王国(1830年 - ) | |||||||

| ルクセンブルク大公国 (1890年 - ) | ||||||||

オーストリア連邦国

[編集]- オーストリア連邦国

- Bundesstaat Österreich

-

←

1934年 - 1938年  →

→

(国旗) (国章) - 国歌: Sei gesegnet ohne Ende

終わりなき祝福あらんことを

オーストリア連邦国の位置(1938年)-

公用語 ドイツ語(オーストリアドイツ語) 宗教 キリスト教(カトリック、東方正教、プロテスタント)、ユダヤ教 首都 ウィーン - 大統領

-

1934年 - 1938年 ヴィルヘルム・ミクラス - 首相

-

1934年 - 1934年 エンゲルベルト・ドルフース 1934年 - 1938年 クルト・シュシュニック 1938年 - 1938年 アルトゥル・ザイス=インクヴァルト - 変遷

-

5月憲法 1934年5月1日 ドルフースの暗殺 1934年7月25日 ベルヒテスガーデン合意 1938年2月12日 アンシュルス 1938年3月13日

通貨 オーストリア・シリング 現在  オーストリア

オーストリア

| オーストリアの歴史 | |

|---|---|

この記事はシリーズの一部です。 | |

| 先史時代から中世前半 | |

| ハルシュタット文化 | |

| 属州ノリクム | |

| マルコマンニ | |

| サモ王国 | |

| カランタニア公国 | |

| オーストリア辺境伯領 | |

| バーベンベルク家、ザルツブルク大司教領、ケルンテン公国、シュタイアーマルク公国 | |

| 小特許状 | |

| ハプスブルク時代 | |

| ハプスブルク家 | |

| 神聖ローマ帝国 | |

| オーストリア大公国 | |

| ハプスブルク君主国 | |

| オーストリア帝国 | |

| ドイツ連邦 | |

| オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国 | |

| 第一次世界大戦 | |

| サラエヴォ事件 | |

| 第一次世界大戦 | |

| 両大戦間期 | |

| オーストリア革命 | |

| ドイツ・オーストリア共和国 | |

| 第一共和国 | |

| オーストロファシズム | |

| アンシュルス | |

| 第二次世界大戦 | |

| ナチズム期 | |

| 第二次世界大戦 | |

| 戦後 | |

| 連合軍軍政期 | |

| オーストリア共和国 | |

| 関連項目 | |

| ドイツの歴史 | |

| リヒテンシュタインの歴史 | |

| ハンガリーの歴史 | |

オーストリア ポータル |

オーストリア連邦国(オーストリアれんぽうこく、ドイツ語: Bundesstaat Österreich、口語ではStändestaat、企業国家と呼ばれる)は、1934年から1938年まで存在した、祖国戦線が率いる一党独裁国家であったオーストリア第一共和国の継承国家である。この国家は1938年3月のアンシュルス(ナチス・ドイツによるオーストリアの併合)で終焉を迎えた。以後、オーストリアは1955年のオーストリア国家条約で連合国軍による占領が終わるまで、再び独立国となることはなかった。

歴史

[編集]

1890年代、カール・フォン・フォーゲルザンクのようなキリスト教社会党(CS)の設立者たちと、ウィーン市長カール・ルエーガーは、プロレタリアートと中産階級の貧困化を考慮した主に経済的な観点からにも関わらず、既に反自由主義的観点を育んでいた[9]。though primarily from an economic perspective considering the pauperization of the proletariat and the lower middle class. Strongly referring to the doctrine of Catholic social teaching, the CS agitated against the Austrian labour movement led by the Social Democratic Party of Austria.

自主クーデター

[編集]

During the Great Depression in the First Austrian Republic of the early 1930s, the CS on the basis of the Quadragesimo anno encyclical issued by Pope Pius XI in 1931 pursued the idea of overcoming the ongoing class struggle by the implementation of a corporative form of government modelled on Italian fascism and Portugal’s Estado Novo. The CS politician Engelbert Dollfuss, appointed Chancellor of Austria in 1932, on 4 March 1933 saw an opportunity in the resignation of Social Democrat Karl Renner as president of the Austrian Nationalrat, after irregularities occurred during a voting process. Dollfuss called the incident a "self-elimination" (Selbstausschaltung) of the parliament and had the following meeting on 15 March forcibly prorogued by the forces of the Vienna police department. His fellow CS party member, President Wilhelm Miklas, analogous to Adolf Hitler's victory in the German elections of 5 March 1933 did not take any action to restore democracy.

Chancellor Dollfuss then governed by emergency decree, banning the Communist Party on 26 May 1933, the Social Democratic Republikanischer Schutzbund paramilitary organization on 30 May and the Austrian branch of the Nazi Party on 19 June. On 20 May 1933 he had established the Fatherland's Front as a unity party of "an autonomous, Christian, German, corporative Federal State of Austria". On 12 February 1934 the government's attempts to enforce the ban of the Schutzbund at the Hotel Schiff in Linz sparked the Austrian Civil War. The revolt was suppressed with support by the Bundesheer and right-wing Heimwehr troops under Ernst Rüdiger Starhemberg, and ended with the ban of the Social Democratic Party and the trade unions. The path to dictatorship was completed on 1 May 1934, when the Constitution of Austria was recast into a severely authoritarian document by a rump National Council.

Dollfuss continued to rule by emergency measures until his assassination on 25 July 1934 during the Nazi July Putsch. Although the coup d'état initially had the encouragement of Hitler, it was quickly suppressed and Dollfuss's education minister, Kurt Schuschnigg, succeeded him. Hitler officially denied any involvement in the failed coup, but he continued to destabilise the Austrian state by secretly supporting Nazi sympathisers like Arthur Seyss-Inquart and Edmund Glaise-Horstenau. In turn Austria under Schuschnigg sought the backing of its southern neighbour, the fascist Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. Tables turned after the Second Italo-Abyssinian War of 1935–36, when Mussolini, internationally isolated, approached Hitler. シュシュニッヒは、オーストリア・ナチス数名を恩赦し、祖国戦線に受け入れることでナチス・ドイツとの関係改善を図ったが、1936年11月1日にムッソリーニが宣言したベルリン・ローマ枢軸に対して勝てる見込みは全くなかった。

一揆失敗の理由の一つに、イタリアの介入があった。Mussolini assembled an army corps of four divisions on the Austrian border and threatened Hitler with a war with Italy in the event of a German invasion of Austria as originally planned, should the coup have been more successful. Support for the Nazi movement in Austria was surpassed only by that in Germany, allegedly amounting to 75% in some areas.[10]

思想

[編集]オーストリア連邦国はオーストリアの歴史を美化した。ハプスブルク期は、オーストリアの歴史上、偉大な時代として位置づけられている。 カトリック教会は、国民がオーストリアの歴史とアイデンティティを決める上で大きな役割を果たし、またドイツ文化の疎外につながった。ヒトラーの比較的世俗的な政権とは異なり、カトリック教会は様々な問題において顕著な発言力を持つようになった。教育面では、国家が学校を非世俗化し、「マトゥーラ」と呼ばれる卒業試験のために宗教教育を義務づけた。このイデオロギーによれば、オーストリア人は「より優れたドイツ人」であった[11]。政権のカトリック主義に則って、教皇回勅の非共産主義・非資本主義の教え、中でも「クアドラゲシモ・アンノ」を高く評価した。

オーストリア連邦国が名目上コーポラティズムを受け入れ、自由資本主義を敬遠していたにもかかわらず、ナチス・ドイツやファシスト・イタリアとは対照的に、極めて資本主義的な金融政策を追求していた。クーデター前にドルフースと協力していた資本主義経済学者のルートヴィヒ・フォン・ミーゼスがオーストリア商工会議所の議長となり、ミーゼスをはじめとする経済学者の指導のもと、オーストリア連邦国は大恐慌の反動で精力的に緊縮財政政策を進めた[12]。

オーストリア連邦国は、通貨バランスをとるために厳しいデフレ政策をとった。また、歳出を大幅に削減し、高金利が常態化した。2億シリング以上あった財政赤字は、5千万シリング以下にまで削減された[13]。しかし、1936年には、失業者の50%しか失業手当を受けられなくなっていた。このような政策は、壊滅的な経済収縮と重なった。アンガス・マディソンの推計によると、失業率は1933年の26%をピークに、1937年まで20%を切ることがなかった[14]。これは、ドイツの失業率が1932年の30%をピークに、1937年までには5%以下にまで低下したことと対照的である。加えて、実質GDPは崩壊し、1937年まで1929年以前の水準に戻ることはなかった。

オーストリア連邦国が純粋にファシズムと言えるかどうかは議論の余地がある。権威主義的で、ファシスト的なシンボルが使われていたが、オーストリア人の間で広い支持を得ることはなかった。連邦国の最も顕著な政策は、カトリックの受容であり、その経済・社会政策は、ファシスト・イタリアやナチス・ドイツの政策とほんの少し類似している。

市民権

[編集]John Gunther wrote in 1940 that the state "assaulted the rights of citizens in a fantastic manner", noting that in 1934 the police raided 106,000 homes in Vienna and made 38,141 arrests of Nazis, social democrats, liberals and communists. He added, however:[15]

But—and it was an important "but"—the terror never reached anything like the repressive force of the Nazi terror. Most of those arrested promptly got out of jail again. Even at its most extreme phase, it was difficult to take the Schuschnigg dictatorship completely seriously, although Schutzbunders tried in 1935 got mercilessly severe sentences. This was because of Austrian gentleness, Austrian genius for compromise, Austrian love for cloudy legal abstractions, and Austrian Schlamperei.

アンシュルス

[編集]According to the Hossbach Memorandum, Hitler in November 1937 declared his plans for an Austrian campaign in a meeting with Wehrmacht commanders. Under the mediation of the German ambassador Franz von Papen, Schuschnigg on 12 February 1938 traveled to Hitler's Berghof residence in Berchtesgaden, only to be confronted with an ultimatum to readmit the Nazi Party and to appoint Seyss-Inquart and Glaise-Horstenau ministers of the Austrian cabinet. Schuschnigg, impressed by the presence of OKW chief General Wilhelm Keitel, gave in and on 16 February Seyss-Inquart became head of the strategically important Austrian interior ministry.

After the British ambassador to Berlin, Nevile Henderson on 3 March 1938 had stated that the German claims to Austria were justified, Schuschnigg started a last attempt to retain Austrian autonomy by scheduling a nationwide referendum on 13 March. As part of his effort to ensure victory, he released the Social Democratic leaders from prison and gained their support in return for dismantling the one-party state and legalizing the socialist trade unions. Hitler reacted with the mobilization of Wehrmacht troops at the Austrian border and demanded the appointment of Seyss-Inquart as Austrian chancellor. On 11 March Austrian Nazis stormed the Federal Chancellery and forced Schuschnigg to resign. Seyss-Inquart was sworn in as his successor by Miklas and the next day Wehrmacht troops crossed the border meeting no resistance.

当初、ヒトラーはオーストリアをセイス=インカートを首班とする傀儡国家として維持するつもりであった。 However, the enthusiastic support for Hitler led him to change his stance and support a full Anschluss between Austria and Nazi Germany. On 13 March Seyss-Inquart formally decreed the Anschluss, though President Miklas avoided signing the law by resigning immediately. Seyss-Inquart then took over most of Miklas' duties and signed the Anschluss bill into law. Two days later in his speech at the Vienna Heldenplatz, Hitler proclaimed the "accession of my homeland to the German Reich" (see Austria in the time of National Socialism).

脚注

[編集]- ^ Knut, Helle (2003). The Cambridge History of Scandinavia: Prehistory to 1520. Cambridge University Press. p. 269. ISBN 0-521-47299-7

- ^ King of Denmark, Valdemar; Svend Aakjær (1926) (デンマーク語). Kong Valdemars Jordebog. Jørgensen

- ^ Monumenta Livoniae Antiquae. E. Frantzen. (1842). p. 36

- ^ Demographics of the Netherlands Archived 2011-12-26 at the Wayback Machine., Jan Lahmeyer. Retrieved on 20 February 2014.

- ^ Pérez, Yolanda Robríguez (2008). The Dutch Revolt through Spanish eyes: self and other in historical and literary texts of Spanish Golden Age (c. 1548–1673) (Transl. and rev. ed.). Oxford: Peter Lang. p. 18. ISBN 978-3-03911-136-7 5 April 2016閲覧。

- ^ “The States General.” Staten Generaal, www.staten-generaal.nl/begrip/the_states_general.

- ^ Koenigsberger, H. G. (2001). Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521803304.

- ^ Bromley, J.S. (editor) 1970, The New Cambridge Modern History Volume 6: The Rise of Great Britain and Russia, 1688–1715/25, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521075244 (p. 428)

- ^ Chaloupek, Günther; ‘Conservative and Liberal Catholic Though in Austria’, in Chaloupek, Günther, Backhaus, Jürgen and Framback, Hans A. (editors); On the Economic Significance of the Catholic Social Doctrine. 125 Years of Rerum Novarum; pp. 73-75 ISBN 3319525441

- ^ “AUSTRIA: Eve of Renewal”. Time. (25 September 1933). オリジナルのNovember 6, 2012時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Ryschka, Birgit (1 January 2008). Constructing and Deconstructing National Identity: Dramatic Discourse in Tom Murphy's The Patriot Game and Felix Mitterer's In Der Löwengrube. Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631581117

- ^ Hoppe, Hans-Hermann (1997年). “The Meaning of the Mises Papers”. mises.org. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Berger, Peter (2003). The League of Nations and Interwar Austria: Critical Assessment of a Partnership in Economic Reconstruction. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. pp. 90

- ^ Maddison, Angus (1982). Phases of Capitalist Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 206

- ^ Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 416

さらに読む

[編集]- Stephan Neuhäuser: “Wir werden ganze Arbeit leisten“- Der austrofaschistische Staatsstreich 1934, ISBN 3-8334-0873-1

- Emmerich Tálos, Wolfgang Neugebauer: Austrofaschismus. Politik, Ökonomie, Kultur. 1933–1938. 5th Edition, Münster, Austria, 2005, ISBN 3-8258-7712-4

- Hans Schafranek: Sommerfest mit Preisschießen. Die unbekannte Geschichte des NS-Putsches im Juli 1934. Czernin Publishers, Vienna 2006.

- Hans Schafranek: Hakenkreuz und rote Fahne. Die verdrängte Kooperation von Nationalsozialisten und Linken im illegalen Kampf gegen die Diktatur des 'Austrofaschismus'. In: Bochumer Archiv für die Geschichte des Widerstandes und der Arbeit, No.9 (1988), pp. 7 – 45.

- Jill Lewis: Austria: Heimwehr, NSDAP and the Christian Social State (in Kalis, Aristotle A.: The Fascism Reader. London/New York)

- Lucian O. Meysels: Der Austrofaschismus – Das Ende der ersten Republik und ihr letzter Kanzler. Amalthea, Vienna and Munich, 1992

- Erika Weinzierl: Der Februar 1934 und die Folgen für Österreich. Picus Publishers, Vienna 1994

- Manfred Scheuch: Der Weg zum Heldenplatz. Eine Geschichte der österreichischen Diktatur 1933–1938. Publishing House Kremayr & Scheriau, Vienna 2005, ISBN 978-3-218-00734-4

- Andreas Novak: Salzburg hört Hitler atmen: Die Salzburger Festspiele 1933–1944. DVA, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-421-05883-0.

- David Schnaiter: Zwischen Russischer Revolution und Erster Republik. Die Tiroler Arbeiterbewegung gegen Ende des "Großen Krieges". Grin Verlag, Ravensburg (2007). ISBN 3-638-74233-4, ISBN 978-3-638-74233-7

ノルウェー王国 (872年-1397年)

[編集]- ノルウェー王国

- ᚴᚮᚿᚢᚿᚴᛋᚱᛁᚴᛁ ᚾᚢᚱᛁᚴᛁ (Younger Futhark)[1]

Konungsríki Nuríki [1]

ᚴᚬᚾᚢᚾᚴᛋᚱᛁᚴᛁ ᚿᚮᚱᛂᚵᚱ (Medieval Futhork)

Konungsríki Noregr

Konungsríki Noregi (中世ノルウェー語)

Kongeriket Noreg

Kongeriket Norge -

←

←

←

872年 - 1397年  →

→ →

→

(国旗) (国章)

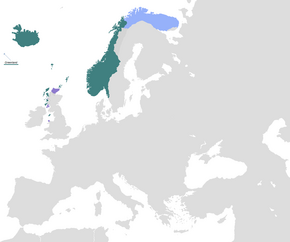

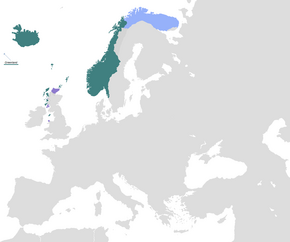

ノルウェーの最大版図(1263頃)-

言語

文字- Younger Futhark

(872年 - 1100年)

中世ルーン文字

(1100年 - 1397年)

ラテン文字

(1015年 - 1397年)

国教 宗教 - サーミ・シャーマニズム

(Finno-Ugricの間で) - goðlauss (lack of faith in any deity)

首都 Ǫgvaldsnes (Avaldsnes)

(872年 - 997年)

Niðaróss(トロンハイム)

(997年 - 1016年、1030年 - 1111年、1150年 - 1217年)

Borg(サルプスボル)

(1016年 - 1030年)

Konungahella (クングエルブ)

(1111年 - 1150年)

ベルゲン

(1217年 - 1314年)

オスロ

(1314年 - 1397年)通貨 ノルウェー・ペニング

(995年 - 1397年)現在  ノルウェー

ノルウェー スウェーデン

スウェーデン イギリス

イギリス アイスランド

アイスランド デンマーク

デンマーク

- Younger Futhark

ノルウェー王国(ノルウェーおうこく、古ノルド語: Noregsveldi、ブークモール: Norgesveldet、ニーノシュク: Noregsveldet)とは、9世紀の終わりにハーラル1世によって統一された、ノルウェー最初の統一王国である。王国は、何世紀にもわたってノルウェー人船員によって開拓されて、「税領域」として王国に併合・編入された海外領だけでなく、現代のノルウェーにあたる地域や、現代のスウェーデンにあたる地域であるイェムトランド州、ヘリェダーレン地方、ランリケ(ブーヒュースレーン地方)、イドレとセルナを含む、緩やかにまとまった国家であった。また、ノルウェーの北側には本土の広大な税領域が隣接していた。ノルウェーは、872年の建国から対外膨張主義を進め、1240年から1319年にかけて最盛期を迎えた。

1130年から1240年にかけて起こった内戦以前、ノルウェーの領土拡大の最盛期には、シグル1世 (ノルウェー王)がノルウェー十字軍(1107年 - 1110年)を率いた。十字軍は、リスボンやバレアレス諸島での戦いに勝利した。Siege of Sidonでは、彼らはボードゥアン1世やOrdelafo Falieroに味方して戦い、この包囲によってエルサレム王国が拡大した[2]。レイフ・エリクソン, an Icelander of Norwegian origin and official hirdman of 国王オーラヴ1世, コロンブスの500年前にアメリカを探検した[3]。ブレーメンのアダム wrote about the new lands in "Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum" (1076) when meeting Sweyn I of Denmark, but no other sources indicate that this knowledge went farther into Europe than Bremen, Germany. The Kingdom of Norway was the second European country after England to enforce a unified code of law to be applied for the whole country, called Magnus Lagabøtes landslov (1274).

世俗的な力は、国王ホーコン・ホーコンソンの統治の終わり頃の1263年が最も強かった。この時代の重要な要素は、1152年以降のニダロス大司教区の教会的な優位性である。There are no reliable sources for when Jämtland was placed under the 大司教 of ウプサラ. ウプサラは後に設立され、ルンドとNidarosに次ぐスカンディナヴィアで3番目の大都市教区であった。The church participated in a political process both before and during the カルマル同盟 that aimed at[要説明] Swedish side, to establish a position for Sweden in Jämtland. This area had been a borderland in relation to the Swedish kingdom, and probably in some sort of alliance with Trøndelag, just as with Hålogaland.

A unified realm was initiated by King ハーラル1世 in the 9th century. His efforts in unifying the petty kingdoms of Norway resulted in the first known Norwegian central government. The country, however, soon fragmented, and was again collected into one entity in the first half of the 11th century. Norway has been a monarchy since Fairhair, passing through several eras.

日本占領時期のグアム(にほんせんりょうじきのグアム)は、第二次世界大戦中に大日本帝国軍がグアムを占領した1941年から1944年までのグアムの歴史上の出来事を指す。この時グアム島は「大宮島」に、ハガニアは「明石」に改名された。

ビザンツ帝国の歴史

[編集]- レオ朝(457-518)/レオ朝ビザンツ帝国

英語版en:Leonid Dynasty/en:Byzantine Empire under the Leonid dynasty - ユスティニアヌス朝(518-610)/ユスティニアヌス朝ビザンツ帝国

英語版en:Byzantine Empire under the Justinian dynasty - ヘラクレイオス朝(610-711)/ヘラクレイオス朝ビザンツ帝国

英語版en:Byzantine Empire under the Heraclian dynasty - イサウリア朝(712-802)/イサウリア朝ビザンツ帝国

英語版en:Byzantine Empire under the Isaurian dynasty - ニケフォロス朝(802-813)/ニケフォロス朝ビザンツ帝国

英語版en:Byzantine Empire under the Nikephorian dynasty - アモリア朝(820-867)/アモリア朝ビザンツ帝国

英語版en:Byzantine Empire under the Amorian dynasty - マケドニア王朝 (東ローマ)(867-1056)/マケドニア朝ビザンツ帝国

英語版en:Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty - ドゥーカス朝(1059-1081)/ドゥーカス朝ビザンツ帝国

英語版en:Doukas/en:Byzantine Empire under the Doukas dynasty - コムネノス朝(1081-1185)/コムネノス朝ビザンツ帝国

英語版en:Byzantine Empire under the Komnenos dynasty - アンゲロス朝(1185-1204)/アンゲロス朝ビザンツ帝国

英語版en:Angelos/en:Byzantine Empire under the Angelos dynasty - パレオロゴス朝(1264-1456)/パレオロゴス朝ビザンツ帝国

英語版en:Palaiologos dynasty/en:Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty

ノルウェーの海外領土の一覧

[編集]

ノルウェーの海外領土の一覧(ノルウェーのかいがいりょうどのいちらん)では、ノルウェー王国が現在領有している、または過去に領有していた地域について述べる。

現在の海外領土

[編集]ノルウェーの非法人地域

スヴァールバル諸島とビュルネイ島は、スヴァールバル条約の適用対象である。また、スヴァールバル諸島およびヤンマイエン島として分類のために一緒にされることがある。

現在のノルウェーの属領は、全て南極地域に存在する。

- ピョートル1世島:南極海に存在する島で、1929年から領有している。

- ブーベ島:南大西洋の亜南極に存在する島で、1930年から領有している。

- ドロンニング・モード・ランド:南極のうちノルウェーが1939年から領有を主張している地域。

地図

[編集]

過去のノルウェー本土と属領

[編集]

いわゆる大ノルウェー[4]は、これらの地域を含んでいた。

スコットランドに割譲された属領(第一段階)

[編集]- ヘブリディーズ諸島:700年代から1100年代にかけて植民化された。1100年代から1266年まで伯爵領の一部かつ王室属領だったが、パース条約によってスコットランドに割譲された[5]。

- マン島:850年代から1152年にかけて植民地化された。1152年から1266年まで伯爵領の一部かつ王室属領だったが、パース条約によってスコットランドに割譲された[5]。

- オークニー諸島:800年代から875年にかけて植民地化された。875年から1100年代までは伯爵領で、1194年から1470年までは王室属領だったが、クリスチャン1世によって質権としてスコットランドに割譲された[6]。

- シェトランド諸島:700年代から900年代にかけて植民地化された。900年代から1195年までは伯爵領で、1195年から1470年までは王室属領だったが、クリスチャン1世によって質権としてスコットランドに割譲された[6]。

封臣

[編集]スウェーデンに割譲された本土(第二段階)

[編集]- ブーヒュースレーン地方:800年代から1523年、また1532年から1658年までノルウェーに統合されていたが、ロスキレ条約 (1658年)によってスウェーデンに割譲された[8]。

- IdreとSärna:800年代から1645年にかけてノルウェーに統合されていたブレムセブルー条約によってスウェーデンに割譲された。しかし、国境線は1751年まで公式に引かれなかった[9]。

- イェムトランド地方:1100年代から1645年までノルウェーに統合されていたが、ブレムセブルー条約によってスウェーデンに割譲された[6][10]。

- ヘリエダーレン地方:1200年代から1563年まで、また1570年から1645年までノルウェーに統合されていたが、ブレムセブルー条約によってスウェーデンに割譲された[11]。

Early entity

[編集]デンマークに割譲された属領(第三段階)

[編集]- フェロー諸島:1035年以前に植民され、1035年から1814年の間は王室属領であった。キール条約によってデンマークに割譲された[6]。

- グリーンランド:1261年以前に植民され、1261年から1814年の間は王室属領であった。キール条約によってデンマークに割譲された[6]。

- アイスランド:1262年以前に植民され、1262年から1814年の間は王室属領であった。キール条約によってデンマークに割譲された[6]。

これらの島が実際に割譲された時期については異論がある。1536/37年のデンマークとノルウェーの連合で、ノルウェー王家の領有地をオルデンブルク王が主張したためとする説もある。それでも、その後の公式文書では「ノルウェーの属領」と呼ばれている。また、キール条約には「…ノルウェー王国を構成する諸州は、(中略)その属領(グリーンランド、フェロー諸島、アイスランドを除く)とともに、(中略)完全かつ主権的にスウェーデン国王に属する…」とあり、1814年までノルウェーの一部とみなされていたことが明確に示されている[6]。

グリーンランド東部の事例

[編集]- エイリーク・ラウデス・ランド:グリーンランドの北東の海岸地域。1931年6月27日に領有を主張し、7月10日に併合した。裁判所の決定により1933年にデンマークに授与されるまで統治した[15][16]。

短期間統治された地域

[編集]ウェールズ本土

[編集]デンマーク本土

[編集]スウェーデン本土

[編集]宗主国 – ダブリンとマン

[編集]かつて領有権を主張した地域

[編集]- イングランド王国(現在イギリスの一部):11世紀に数人のノルウェー国王(ハルドラーダ家)によって領有が主張された[24][25]。

- デンマーク王国:11世紀に数人のノルウェー国王(ハルドラーダ家)によって領有が主張された。

- サウスジョージア(現在イギリスの海外領土の一部)。

20世紀初頭にノルウェーの捕鯨産業が南極に拡大したことで、1905年にスウェーデン=ノルウェーから独立したばかりのノルウェーは、ヤンマイエン島とスベルドラップ諸島の領有を主張する北極圏だけでなく、南極大陸にも領土拡大を目指すようになった。ノルウェーはブーベ島の領有を主張し、さらに南下して、南緯45度から南緯65度、西経35度から西経|80度の間の地域の国際的地位について外務省に公式に問い合わせた。1907年3月4日付のノルウェー政府による2度目の外交交渉の後、イギリスは19世紀前半の発見に基づくイギリス領であると回答し、1908年にイギリス領フォークランド諸島の特許状を発行し、1909年にグリトビケンに常設の地方行政機関を設置した[26][27]。

- ゼムリャフランツァヨシファ(現在ロシアの一部):ソビエト連邦の主張を跳ね返し、1926年から1929年の間領有を主張していた[28]。

- スベルドラップ諸島(現在カナダの一部):1902年から、イギリス帝国の一部としてのカナダの宗主権が認められた1930年まで領有を主張していた(代わりにイギリスはヤンマイエン島に対するノルウェーの領有権を認めた。)[29]。

- エイリーク・ラウデス・ランド(グリーンランドの北東の海岸地域):1931年6月27日に領有を主張し、7月10日に併合した。裁判所の決定により1933年にデンマークに授与されるまで統治した[15][30]。

- イナリとペチェングスキー(現在フィンランドとロシアの一部):1942年から1945年まで、ナチ占領下のノルウェーでクヴィスリング政権がフィンランドから領有を主張した[31][32]。

- ムルマンスクとアルハンゲリスク(ビャルマランド)(現在ロシアの一部):1942年から1945年までクヴィスリング政権がソビエト連邦から領有を主張した。またそれ以前には、ノルウェー王国が中世盛期と中世後期に領有を主張した[33]。クヴィスリングは、ノルウェーの植民地化のために確保された地域をビャルマランドと名付けた。これは、サガに登場する北方ロシアの名前にちなんでいる[34][35]。

関連項目

[編集]脚注

[編集]- ^ a b Demir, Sores Welat (January 1, 2019). Norge & Noreg – Norges Historie / (History of Norway – Book by SWD). SWD Group. ISBN 9788284220246

- ^ Thomas Madden, The New Concise History of the Crusades (Rowman and Littlefield, 2005), pp. 40–43.

- ^ Bandlien, Bjørn, ed. (31 January 2020). Leiv Eiriksson. 2020年2月1日閲覧。

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=は無視されます。 (説明) - ^ Larsen, Karen (8 December 2015). History of Norway. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400875795 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Scotland Back in the Day: Young Margaret, the first Queen of Scotland”. The National. 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g “Norgesveldet under lupen - Gemini.no”. Gemini.no (22 June 2015). 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ “Scotland Back in the Day: How Scotland ended its enmity with Norway”. The National. 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ “Bohuslän”. Snl.no (11 April 2017). 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ “Idre”. Snl.no (28 September 2014). 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ “Jämtlands historie”. Snl.no (30 May 2017). 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ “Härjedalens historie”. Snl.no (20 June 2017). 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ "När blev Värmland en del av det svenska riket?" by Dick Harrison, Professor of history at the University of Lund. Svenska Dagbladet. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ Smilely, Jane (24 February 2005). The Sagas of the Icelanders. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141933269 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ “Haralds saga hins hárfagra – heimskringla.no”. heimskringla.no. 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ a b 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグです。「eastgreeland」という名前の注釈に対するテキストが指定されていません - ^ “Legal Status of Eastern Greenland, Denmark v. Norway, Judgment, 5 September 1933, Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ)”. Worldcourts.com. 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ The Heimskringla: Or, Chronicle of the Kings of Norway. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. (1844) 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ “Tillbaka till tiden då Halland var ett land”. Hn.se. 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ Granberg, Per A. (3 October 2017). “Skandinaviens historia under konungarne of Folkunga-Ätten”. Elmén och Granberg. 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ Kent, Neil (12 June 2008). A Concise History of Sweden. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107782587 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ Adams, Jonathan (15 October 2015). The Revelations of St Birgitta: A Study and Edition of the Birgittine-Norwegian Texts, Swedish National Archives, E 8902. BRILL. ISBN 9789004304666 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ Ulwencreutz, Lars (11 June 2015). Från Oden till Vasa. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781329073661 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ a b Somerled: Hammer of the Norse

- ^ “BBC – History : British History Timeline”. Bbc.co.uk. 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ “Invasion of England, 1066”. Eyewitnesstohistory.com. 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ Odd Gunnar Skagestad. Norsk Polar Politikk: Hovedtrekk og Utvikslingslinier, 1905–1974. Oslo: Dreyers Forlag, 1975

- ^ Thorleif Tobias Thorleifsson. Bi-polar international diplomacy: The Sverdrup Islands question, 1902–1930. Master of Arts Thesis, Simon Fraser University, 2004.

- ^ Barr (1995): 96

- ^ Berton, Pierre. The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole. Toronto: Random House of Canada Ltd., 1988, p. 629.

- ^ “Legal Status of Eastern Greenland, Denmark v. Norway, Judgment, 5 September 1933, Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ)”. Worldcourts.com. 3 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ Kurt D. Singer (1943). Duel for the northland: the war of enemy agents in Scandinavia. R. M. McBride & company. p. 200 2020年12月11日閲覧。

- ^ Skodvin, M. (1990). Norge i krig: Frigjøring. Aschehoug. ISBN 9788203114236 2015年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Norway's Nazi collaborators sought Russia colonies”. Associated Press. Fox News. (9 April 2010) 4 March 2017閲覧。

- ^ Dahl (1999), p. 296

- ^ Hans Fredrik Dahl (1999). Quisling: a study in treachery. Cambridge University Press, p. 343 [1]

- ^ “Medieval Iceland: The Rise and Fall of the Commonwealth AD 870–1264”. nicolejwallace.freeservers.com. 3 October 2017閲覧。