FUS

FUS(fused in sarcoma)は、ヒトではFUS遺伝子にコードされるタンパク質である。TLS(translocated in liposarcoma)、hnRNP P2(heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein P2)としても知られる[5][6][7][8][9][10]。

発見

[編集]FUS/TLSは当初、ヒトのがん、特に脂肪肉腫において染色体転座によって産生されるようになる融合タンパク質(FUS-CHOP)として同定された[6][9]。これらの例では、FUS/TLSのプロモーター領域とN末端部分がさまざまなDNA結合型転写因子(CHOPなど)のC末端ドメインへ転座した結果、融合タンパク質に強力な転写活性化能が生じている[11][12]。

またそれとは独立に、FUS/TLSはpre-mRNAの成熟に関与する複合体のサブユニットhnRNP P2タンパク質としても同定された[13]。

構造

[編集]FUS/TLSはFETファミリーの一員であり、このファミリーには他にEWS、TBP随伴因子TAFII68/TAF15、ショウジョウバエのcabeza/SARFタンパク質などが含まれる[11][14]。

FUS/TLS、EWS、TAF15は類似した構造を持ち、N末端のQGSYリッチ領域、高度に保存されたRNA認識モチーフ(RRM)、アルギニン残基が広くジメチル化された複数のRGGリピート[15]、C末端のジンクフィンガーモチーフによって特徴づけられる[7][9][14][16]。

機能

[編集]FUSのN末端領域は転写活性化、C末端領域はタンパク質やRNAへの結合に関与しているようである。また、FUS遺伝子には、AP-2、GCF、Sp1などの転写因子の認識部位が同定されている[17]。

In vitroでは、FUS/TLSはRNA、一本鎖DNA、そして(低い親和性で)二本鎖DNAに結合することが示されている[7][9][18][19][20][21]。FUS/TLSのRNAやDNAへの結合の配列特異性ははっきりしていないが、SELEX法では、FUS/TLSが結合するRNA配列の約半数に共通するGGUGモチーフが同定されている[22]。GGUGモチーフはRRMではなく、ジンクフィンガードメインによって認識されていることが後に提唱されている。さらに、FUS/TLSはアクチン安定化タンパク質Nd1-LのmRNAの3' UTR上の比較的長い領域に結合することが知られており、特定の短い配列を認識するのではなく、複数のモチーフや二次構造と相互作用することが示唆されている[23]。FUS/TLSはin vitroではヒトのテロメアRNA(UUAGGG)4や一本鎖テロメアDNAにも結合する[24]。

核酸への結合の他にも、FUS/TLSは転写開始に影響を与える基本転写因子やより専門的な因子とも結合することが知られている[25]。FUS/TLSはいくつかの核内受容体[26]やSpi-1/PU.1などの遺伝子特異的転写因子[27]、NF-κB[28]などと相互作用する。基本転写装置とも結合し、RNAポリメラーゼIIやTFIID複合体と相互作用して転写開始やプロモーターの選択に影響を与えている可能性がある[29][30][31]。また、FUS/TLSはRNAポリメラーゼIIIによる転写を抑制し、TBPやTFIIIB複合体と共免沈されることが示されている[32]。

FUSを介したDNA修復

[編集]FUSはDNA損傷部位に非常に迅速に出現し、DNA修復応答を指揮していることが示唆される[33]。神経細胞におけるDNA損傷応答におけるFUSの機能には、ヒストンデアセチラーゼHDAC1との直接的な相互作用が関与している。二本鎖切断部位へのFUSのリクルートはDNA損傷シグナルの伝達、そしてDNA損傷修復に重要である[33]。神経細胞では、FUSの機能喪失によってDNA損傷が増加する。FUSの核局在配列の変異はPARP依存的なDNA損傷応答の機能不全をもたらす[34]。その結果、神経変性とFUS凝集体の形成が引き起こされる。こうしたFUS凝集体は筋萎縮性側索硬化症(ALS)の病理的特徴の1つである。

臨床的意義

[編集]FUS遺伝子の再編成は、粘液型脂肪肉腫、低悪性度線維粘液性肉腫、ユーイング肉腫その他のさまざまな悪性・良性腫瘍の病因への関与が示唆されている[35]。

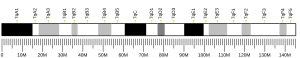

2009年に2つの異なる研究グループによってALS6型の表現型を示す無関係な26家族の解析が行われ、FUS遺伝子に14種類の変異が発見された[36][37]。

続いて、FUSは前頭側頭型認知症(FTD)のサブグループ、それまで神経細胞性中間径フィラメント封入体病(NIFID)として知られていた、ユビキチン封入体陽性、TDP-43やタウ封入体陰性、そして封入体の一部にα-インターネキシンが含まれることで特徴づけられていたサブグループにおいて、FUSが重要な病因タンパク質として浮上した。現在、FUS封入体を有する前頭側頭葉変性症(FTLD-FUS)のサブタイプとみなされている疾患には、ユビキチン封入体を伴う非定型的FTLD(aFTLD-U)、NIFID、好塩基性封入体病(BIBD)があり、ALS-FUSとともにFUS-プロテオパチーを構成している[38][39][40][41]。

ALSにおける毒性機構

[編集]変異型FUSがALSを引き起こす毒性の機構は現在のところ不明である。ALSと関連した変異の多くがC末端の核局在シグナルに位置していることが知られており、そのため野生型FUSは主に核に局在するのに対し、これらの変異型FUSは細胞質に局在する[42]。このことは、核内機能の喪失もしくは細胞質機能による毒性の獲得のいずれかがこのタイプのALSの発症の原因となっていることを示唆している。FUSを発現しないマウスモデル(そのため核内のFUSの機能を完全に喪失する)では明確なALS様症状は出現しないため、多くの研究者は細胞質機能による毒性の獲得の可能性が高いと考えている[43]。

相互作用

[編集]FUSは次に挙げる因子と相互作用することが示されている。

- FUSIP1/SRSF10[31]

- HDAC1[33]

- ILF3[44]

- PRMT1[45][46][47]

- RELA[28]

- RNAポリメラーゼII(CTD)[48]

- SPI1[27]

- TNPO1[49][50]

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000089280 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000030795 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Localization of the chromosomal breakpoints of the t(12;16) in liposarcoma to subbands 12q13.3 and 16p11.2”. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 48 (1): 101–7. (Aug 1990). doi:10.1016/0165-4608(90)90222-V. PMID 2372777.

- ^ a b “Fusion of the dominant negative transcription regulator CHOP with a novel gene FUS by translocation t(12;16) in malignant liposarcoma”. Nat Genet 4 (2): 175–80. (Sep 1993). doi:10.1038/ng0693-175. PMID 7503811.

- ^ a b c “TLS/FUS fusion domain of TLS/FUS-erg chimeric protein resulting from the t(16;21) chromosomal translocation in human myeloid leukemia functions as a transcriptional activation domain”. Oncogene 9 (12): 3717–29. (December 1994). PMID 7970732.

- ^ “Entrez Gene: FUS fusion (involved in t(12;16) in malignant liposarcoma)”. 2022年9月10日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “Fusion of CHOP to a novel RNA-binding protein in human myxoid liposarcoma”. Nature 363 (6430): 640–4. (June 1993). Bibcode: 1993Natur.363..640C. doi:10.1038/363640a0. PMID 8510758.

- ^ “Chromosome 12 breakpoints are cytogenetically different in benign and malignant lipogenic tumors: localization of breakpoints in lipoma to 12q15 and in myxoid liposarcoma to 12q13.3”. Cancer Res. 53 (7): 1670–5. (April 1993). PMID 8453640.

- ^ a b “The N-terminal domain of human TAFII68 displays transactivation and oncogenic properties”. Oncogene 18 (56): 8000–10. (December 1999). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203207. PMID 10637511.

- ^ “A novel effector domain from the RNA-binding protein TLS or EWS is required for oncogenic transformation by CHOP”. Genes Dev. 8 (21): 2513–26. (November 1994). doi:10.1101/gad.8.21.2513. PMID 7958914.

- ^ “Identification of hnRNP P2 as TLS/FUS using electrospray mass spectrometry”. RNA 1 (7): 724–33. (September 1995). PMC 1369314. PMID 7585257.

- ^ a b “Genomic structure of the human RBP56/hTAFII68 and FUS/TLS genes”. Gene 221 (2): 191–8. (October 1998). doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00463-6. PMID 9795213.

- ^ “Detection of arginine dimethylated peptides by parallel precursor ion scanning mass spectrometry in positive ion mode”. Anal. Chem. 75 (13): 3107–14. (July 2003). doi:10.1021/ac026283q. PMID 12964758.

- ^ “Domain architectures and characterization of an RNA-binding protein, TLS”. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (43): 44834–40. (October 2004). doi:10.1074/jbc.M408552200. PMID 15299008.

- ^ “Expression patterns of the human sarcoma-associated genes FUS and EWS and the genomic structure of FUS”. Genomics 37 (1): 1–8. (October 1996). doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0513. PMID 8921363.

- ^ “TLS (FUS) binds RNA in vivo and engages in nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling”. J. Cell Sci. 110 (15): 1741–50. (August 1997). doi:10.1242/jcs.110.15.1741. PMID 9264461.

- ^ “TLS/FUS, a pro-oncogene involved in multiple chromosomal translocations, is a novel regulator of BCR/ABL-mediated leukemogenesis”. EMBO J. 17 (15): 4442–55. (August 1998). doi:10.1093/emboj/17.15.4442. PMC 1170776. PMID 9687511.

- ^ “Human 75-kDa DNA-pairing protein is identical to the pro-oncoprotein TLS/FUS and is able to promote D-loop formation”. J. Biol. Chem. 274 (48): 34337–42. (November 1999). doi:10.1074/jbc.274.48.34337. PMID 10567410.

- ^ “Induced ncRNAs allosterically modify RNA-binding proteins in cis to inhibit transcription”. Nature 454 (7200): 126–30. (July 2008). Bibcode: 2008Natur.454..126W. doi:10.1038/nature06992. PMC 2823488. PMID 18509338.

- ^ “Identification of an RNA binding specificity for the potential splicing factor TLS”. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (9): 6807–16. (March 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M008304200. PMID 11098054.

- ^ “TLS facilitates transport of mRNA encoding an actin-stabilizing protein to dendritic spines”. J. Cell Sci. 118 (Pt 24): 5755–65. (December 2005). doi:10.1242/jcs.02692. PMID 16317045.

- ^ “Identification of RNA binding specificity for the TET-family proteins”. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf) 52 (52): 213–4. (2008). doi:10.1093/nass/nrn108. PMID 18776329.

- ^ “TLS, EWS and TAF15: a model for transcriptional integration of gene expression”. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic 5 (1): 8–14. (March 2006). doi:10.1093/bfgp/ell015. PMID 16769671.

- ^ “TLS (translocated-in-liposarcoma) is a high-affinity interactor for steroid, thyroid hormone, and retinoid receptors”. Mol. Endocrinol. 12 (1): 4–18. (January 1998). doi:10.1210/mend.12.1.0043. PMID 9440806.

- ^ a b “The transcription factor Spi-1/PU.1 interacts with the potential splicing factor TLS”. J. Biol. Chem. 273 (9): 4838–42. (February 1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.9.4838. PMID 9478924.

- ^ a b “Involvement of the pro-oncoprotein TLS (translocated in liposarcoma) in nuclear factor-kappa B p65-mediated transcription as a coactivator”. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (16): 13395–401. (April 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M011176200. PMID 11278855.

- ^ “hTAF(II)68, a novel RNA/ssDNA-binding protein with homology to the pro-oncoproteins TLS/FUS and EWS is associated with both TFIID and RNA polymerase II”. EMBO J. 15 (18): 5022–31. (September 1996). doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00882.x. PMC 452240. PMID 8890175.

- ^ “EWS, but not EWS-FLI-1, is associated with both TFIID and RNA polymerase II: interactions between two members of the TET family, EWS and hTAFII68, and subunits of TFIID and RNA polymerase II complexes”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 (3): 1489–97. (March 1998). doi:10.1128/mcb.18.3.1489. PMC 108863. PMID 9488465.

- ^ a b “TLS-ERG leukemia fusion protein inhibits RNA splicing mediated by serine-arginine proteins”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 (10): 3345–54. (May 2000). doi:10.1128/MCB.20.10.3345-3354.2000. PMC 85627. PMID 10779324.

- ^ “TLS inhibits RNA polymerase III transcription”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30 (1): 186–96. (January 2010). doi:10.1128/MCB.00884-09. PMC 2798296. PMID 19841068.

- ^ a b c “Interaction of FUS and HDAC1 regulates DNA damage response and repair in neurons”. Nature Neuroscience 16 (10): 1383–91. (October 2013). doi:10.1038/nn.3514. PMC 5564396. PMID 24036913.

- ^ “Impaired DNA damage response signaling by FUS-NLS mutations leads to neurodegeneration and FUS aggregate formation”. Nat Commun 9 (1): 335. (January 2018). Bibcode: 2018NatCo...9..335N. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02299-1. PMC 5780468. PMID 29362359.

- ^ “EWSR1-The Most Common Rearranged Gene in Soft Tissue Lesions, Which Also Occurs in Different Bone Lesions: An Updated Review”. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland) 11 (6): 1093. (June 2021). doi:10.3390/diagnostics11061093. PMC 8232650. PMID 34203801.

- ^ “Mutations in the FUS/TLS Gene on Chromosome 16 Cause Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis”. Science 323 (5918): 1205–1208. (February 2009). Bibcode: 2009Sci...323.1205K. doi:10.1126/science.1166066. PMID 19251627.

- ^ “Mutations in FUS, an RNA processing protein, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 6”. Science 323 (5918): 1208–11. (February 2009). Bibcode: 2009Sci...323.1208V. doi:10.1126/science.1165942. PMC 4516382. PMID 19251628.

- ^ “TDP-43 and FUS in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia”. Lancet Neurol 9 (10): 995–1007. (October 2010). doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70195-2. PMID 20864052.

- ^ “FUS pathology in basophilic inclusion body disease”. Acta Neuropathol. 118 (5): 617–27. (November 2009). doi:10.1007/s00401-009-0598-9. hdl:2429/54671. PMID 19830439.

- ^ “A new subtype of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with FUS pathology”. Brain 132 (Pt 11): 2922–31. (November 2009). doi:10.1093/brain/awp214. PMC 2768659. PMID 19674978.

- ^ “Abundant FUS-immunoreactive pathology in neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease”. Acta Neuropathol. 118 (5): 605–16. (November 2009). doi:10.1007/s00401-009-0581-5. PMC 2864784. PMID 19669651.

- ^ “FUS - RNA-binding protein FUS - Homo sapiens (Human) - FUS gene & protein”. www.uniprot.org. 2019年3月13日閲覧。

- ^ “FUS/TLS deficiency causes behavioral and pathological abnormalities distinct from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis”. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 3: 24. (April 2015). doi:10.1186/s40478-015-0202-6. PMC 4408580. PMID 25907258.

- ^ “Characterization of two evolutionarily conserved, alternatively spliced nuclear phosphoproteins, NFAR-1 and -2, that function in mRNA processing and interact with the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR”. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (34): 32300–12. (August 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M104207200. PMID 11438536.

- ^ “Identification of methylated proteins by protein arginine N-methyltransferase 1, PRMT1, with a new expression cloning strategy”. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1591 (1–3): 1–10. (August 2002). doi:10.1016/S0167-4889(02)00202-1. PMID 12183049.

- ^ “PABP1 identified as an arginine methyltransferase substrate using high-density protein arrays”. EMBO Rep. 3 (3): 268–73. (March 2002). doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvf052. PMC 1084016. PMID 11850402.

- ^ “A human protein-protein interaction network: a resource for annotating the proteome”. Cell 122 (6): 957–68. (September 2005). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.029. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0010-8592-0. PMID 16169070.

- ^ “Residue-by-Residue View of In Vitro FUS Granules that Bind the C-Terminal Domain of RNA Polymerase II.”. Mol. Cell 60 (2): 231–241. (October 15, 2015). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.006. PMC 4609301. PMID 26455390.

- ^ “ALS-associated fused in sarcoma (FUS) mutations disrupt Transportin-mediated nuclear import”. EMBO J. 29 (16): 2841–57. (August 2010). doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.143. PMC 2924641. PMID 20606625.

- ^ “Transportin1: a marker of FTLD-FUS”. Acta Neuropathol. 122 (5): 591–600. (November 2011). doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0863-6. PMID 21847626.

関連文献

[編集]- “Retroviral transduction of TLS-ERG initiates a leukemogenic program in normal human hematopoietic cells”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (14): 8239–44. (July 1998). Bibcode: 1998PNAS...95.8239P. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.14.8239. PMC 20960. PMID 9653171.

- “Inhibition of apoptosis by normal and aberrant Fli-1 and erg proteins involved in human solid tumors and leukemias”. Oncogene 14 (11): 1259–68. (March 1997). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201099. PMID 9178886.

- “Unfolding new mechanisms of alcoholic liver disease in the endoplasmic reticulum”. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21 Suppl 3: S7–9. (2007). doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04581.x. PMID 16958678.

- “Characterization of the CHOP breakpoints and fusion transcripts in myxoid liposarcomas with the 12;16 translocation”. Cancer Res. 54 (24): 6500–3. (1995). PMID 7987849.

- “An RNA-binding protein gene, TLS/FUS, is fused to ERG in human myeloid leukemia with t(16;21) chromosomal translocation”. Cancer Res. 54 (11): 2865–8. (1994). PMID 8187069.

- “Expression patterns of the human sarcoma-associated genes FUS and EWS and the genomic structure of FUS”. Genomics 37 (1): 1–8. (1997). doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0513. PMID 8921363.

- “TLS (FUS) binds RNA in vivo and engages in nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling”. J. Cell Sci. 110 (15): 1741–50. (1997). doi:10.1242/jcs.110.15.1741. PMID 9264461.

- “TLS (translocated-in-liposarcoma) is a high-affinity interactor for steroid, thyroid hormone, and retinoid receptors”. Mol. Endocrinol. 12 (1): 4–18. (1998). doi:10.1210/mend.12.1.0043. PMID 9440806.

- “The transcription factor Spi-1/PU.1 interacts with the potential splicing factor TLS”. J. Biol. Chem. 273 (9): 4838–42. (1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.9.4838. PMID 9478924.

- “The transcriptional repressor ZFM1 interacts with and modulates the ability of EWS to activate transcription”. J. Biol. Chem. 273 (29): 18086–91. (1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.29.18086. PMID 9660765.

- “Oncoprotein TLS interacts with serine-arginine proteins involved in RNA splicing”. J. Biol. Chem. 273 (43): 27761–4. (1998). doi:10.1074/jbc.273.43.27761. PMID 9774382.

- “Human POMp75 is identified as the pro-oncoprotein TLS/FUS: both POMp75 and POMp100 DNA homologous pairing activities are associated to cell proliferation”. Oncogene 18 (31): 4515–21. (1999). doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203048. PMID 10442642.

- “Human 75-kDa DNA-pairing protein is identical to the pro-oncoprotein TLS/FUS and is able to promote D-loop formation”. J. Biol. Chem. 274 (48): 34337–42. (1999). doi:10.1074/jbc.274.48.34337. PMID 10567410.

- “TLS-ERG Leukemia Fusion Protein Inhibits RNA Splicing Mediated by Serine-Arginine Proteins”. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 (10): 3345–54. (2000). doi:10.1128/MCB.20.10.3345-3354.2000. PMC 85627. PMID 10779324.

- “Proteomic analysis of NMDA receptor-adhesion protein signaling complexes”. Nat. Neurosci. 3 (7): 661–9. (2000). doi:10.1038/76615. hdl:1842/742. PMID 10862698.

- “Involvement of the pro-oncoprotein TLS (translocated in liposarcoma) in nuclear factor-kappa B p65-mediated transcription as a coactivator”. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (16): 13395–401. (2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M011176200. PMID 11278855.

- “Characterization of two evolutionarily conserved, alternatively spliced nuclear phosphoproteins, NFAR-1 and -2, that function in mRNA processing and interact with the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR”. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (34): 32300–12. (2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M104207200. PMID 11438536.

- “PABP1 identified as an arginine methyltransferase substrate using high-density protein arrays”. EMBO Rep. 3 (3): 268–73. (2002). doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvf052. PMC 1084016. PMID 11850402.