ケラチノサイト

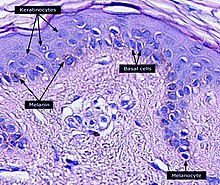

ケラチノサイトまたは角化細胞(かくかさいぼう、英: keratinocyte)は皮膚の最外層の表皮に存在する主要な細胞であり、ヒトでは表皮の細胞の90%を占める[1]。表皮の基底層(stratum basale)に位置する基底細胞は、基底ケラチノサイトまたは基底角化細胞(basal keratinocyte)とも呼ばれる[2]。

機能

[編集]ケラチノサイトの主な機能は、熱、紫外線、脱水、病原性細菌、真菌類、寄生虫、ウイルスによるダメージに対するバリアの形成である。

病原体が表皮の上層に侵入すると、ケラチノサイトによって炎症性メディエーター、特に単球、NK細胞、T細胞、樹状細胞を病原体侵入部位に誘引するCXCL10やCCL2(MCP-1)などのケモカインが産生される[3]。

構造

[編集]多数の構造タンパク質(フィラグリン、ケラチン)、酵素(プロテアーゼ)、脂質、抗菌ペプチド(ディフェンシン)が皮膚の重要なバリア機能の維持に寄与する。Keratinization(角質化、角化)は物理的なバリアの形成(cornification)の一部をなす過程であり、ケラチノサイトはこの過程でより多くのケラチンを産生し、終末分化が行われる。十分に角化したケラチノサイトは皮膚の最外層を形成し、絶えず剥離して新たな細胞に置き換わってゆく[4]。

細胞分化

[編集]表皮幹細胞は表皮の下層(基底層)に位置し、ヘミデスモソームを介して基底膜に接着されている。表皮幹細胞はランダムに分裂し、より多くの幹細胞またはTA細胞(transit amplifying cell)となる[5]。TA細胞の一部は増殖を継続し、その後に分化を行って表皮の表面に向かって移動する。幹細胞とそこから分化した子孫は円柱状に組織化され、表皮増殖単位(epidermal proliferation unit)と呼ばれる[6]。

この分化過程でケラチノサイトは細胞周期から脱し、表皮分化マーカーの発現を開始し、上層へ移動する。有棘層(stratum spinosum)、顆粒層(stratum granulosum)と移動し、最終的には角質層(stratum corneum)の角質細胞(corneocyte)となる。

角質細胞は分化プログラムを完了したケラチノサイトで、細胞核や細胞質のオルガネラを失っている[7]。最終的に、角質細胞は新たな細胞が入ってくると落屑によって剥離する。

分化の各段階でケラチノサイトは、ケラチン1、ケラチン5、ケラチン10、ケラチン14などの特異的ケラチンを発現するが、インボルクリン、ロリクリン、トランスグルタミナーゼ、フィラグリン、カスパーゼ14など他のマーカーも発現する。

ケラチノサイトの幹細胞から落屑までのターンオーバーは、ヒトでは40–56日[8]、マウスでは8–10日[9]と推定されている。

ケラチノサイトの分化を促進する因子としては次のようなものがある。

- カルシウム勾配: カルシウムは基底層で最も低濃度であり、顆粒層の外層で最大となるまで濃度は上昇し続ける。角質層のカルシウム濃度は極めて高いが、この層の比較的乾燥した細胞ではイオンを溶解できないことがその一因である[10]。こうした細胞外のカルシウム濃度の上昇は、ケラチノサイトの細胞内の遊離カルシウム濃度の上昇を誘導する[11]。細胞内カルシウム濃度の上昇の一部は細胞内に貯蔵されていたものの放出によるものであり[12]、残りは膜を越えた流入によるものである[13]。カルシウムは、カルシウム感受性塩素チャネル[14]とカルシウム透過性を有する電位非依存性カチオンチャネル[15]の双方を介して流入する。さらに、細胞外のカルシウムを検知する受容体も細胞内カルシウム濃度の上昇するに寄与する[16]。

- ビタミンD3(コレカルシフェロール): ビタミンD3は主にカルシウム濃度の調節と、分化に関与する遺伝子の発現の調節によって、ケラチノサイトの増殖と分化を調節する[17][18]。ケラチノサイトはビタミンDの産生から異化までの完全なビタミンD代謝経路とビタミンD受容体の発現を有する、体内で唯一の細胞である[19]。

- カテプシンE[20]

- TALEホメオドメイン転写因子[21]

- ヒドロコルチゾン[22]

ケラチノサイトの分化はケラチノサイトの増殖を阻害するため、ケラチノサイトの増殖を促進する因子は分化を防ぐ因子としてみなされる。そうした因子には次のようなものがある。

他の細胞との相互作用

[編集]ケラチノサイトは、表皮のメラノサイトから内在性光防護色素のメラニンを含む小胞であるメラノソームを取り込むことで、紫外線照射から体を保護する。表皮のメラノサイトにはいくつかの樹状突起が存在し、突起を伸ばすことで多くのケラチノサイトを連結している。メラニンはケラチノサイトとメラノサイトの核周辺領域に貯蔵され、核の上の「キャップ」となることで紫外線照射による損傷からDNAを保護する[27]。

創傷治癒における役割

[編集]皮膚の創傷の修復の一部は、ケラチノサイトが移動して創傷によって生じた隙間を埋めることで行われる。修復に最初に関与するケラチノサイトの集団は毛包のバルジ領域に由来するものであり、これらは一過的にしか生存しない。治癒した表皮では、表皮に由来するケラチノサイトによって置き換えられる[28][29]。

反対に、表皮のケラチノサイトは大きな創傷の治癒時に毛包の新規形成に寄与する[30]。

鼓膜穿孔の治癒には機能的なケラチノサイトが必要である[31]。

サンバーンセル

[編集]サンバーンセルは、UVCまたはUVBの照射後、またはソラレン存在下でのUVA照射後に出現する、ピクノーシスを起こした細胞核と好酸性の細胞質を持つケラチノサイトである。未成熟で異常な角質化を示し、アポトーシスの一例として記載されている[32][33]。

老化

[編集]年齢とともに組織の恒常性は低下するが、その一部は幹細胞や前駆細胞は自己複製や分化を行えなくなるためである。幹細胞や前駆細胞への活性酸素種(ROS)の曝露は表皮幹細胞の老化に重要な役割を果たしている可能性がある。通常はミトコンドリアのスーパーオキシドジスムターゼSOD2がROSからの保護を行っているが、マウスの表皮細胞でのSOD2の欠損は一部のケラチノサイトで増殖が不可逆的に停止した細胞老化を引き起こすことが観察されている[34]。老齢マウスでは、SOD2の欠損によって創口閉鎖の遅れと表皮の厚さの減少がみられる[34]。

シバット小体

[編集]

シバット小体またはシバット体(Civatte body、フランスの皮膚科医Achille Civatte(1877–1956)に由来する[35])はアポトーシスを起こした損傷した基底ケラチノサイトであり、ケラチン中間径フィラメントによって大部分が構成され、ほぼ常に免疫グロブリン、主にIgMで覆われている[36]。シバット小体はさまざまな皮膚疾患、特に扁平苔癬や円板状エリテマトーデスの病変部位に特徴的に観察される[36]。また、移植片対宿主病、薬物有害反応、炎症性角化症(苔癬様日光角化症、扁平苔癬様角化症など)、多形紅斑、水疱性類天疱瘡、湿疹、毛孔性扁平苔癬、熱性好中球性皮膚症、中毒性表皮壊死症、単純疱疹と水痘・帯状疱疹の病変部位、疱疹状皮膚炎、晩発性皮膚ポルフィリン症、サルコイドーシス、角層下膿疱症、一過性棘融解性皮膚症、epidermolytic hyperkeratosisでもみられる場合がある[36]。

出典

[編集]- ^ McGrath JA; Eady RAJ; Pope FM. (2004). “Anatomy and Organization of Human Skin”. In Burns T; Breathnach S; Cox N et al.. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology (7th ed.). Blackwell Publishing. p. 4190. doi:10.1002/9780470750520.ch3. ISBN 978-0-632-06429-8 2010年6月1日閲覧。

- ^ Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10th ed.). Saunders. (December 2005). pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6. オリジナルの2010-10-11時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年6月1日閲覧。

- ^ Murphy, Kenneth (Kenneth M.) (2017). Janeway's immunobiology. Weaver, Casey (Ninth ed.). New York, NY, USA. p. 112. ISBN 9780815345053. OCLC 933586700

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F. (2000). “The Epidermis and the Origin of Cutaneous Structures.”. Developmental Biology.. Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0878932436. "Throughout life, the dead keratinized cells of the cornified layer are shed (humans lose about 1.5 grams of these cells each day*) and are replaced by new cells, the source of which is the mitotic cells of the Malpighian layer. Pigment cells (melanocytes) from the neural crest also reside in the Malpighian layer, where they transfer their pigment sacs (melanosomes) to the developing keratinocytes."

- ^ “A keratinocyte's course of life”. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology 20 (3): 122–32. (2007). doi:10.1159/000098163. PMID 17191035.

- ^ “Multiple classes of stem cells in cutaneous epithelium: a lineage analysis of adult mouse skin”. The EMBO Journal 20 (6): 1215–22. (March 2001). doi:10.1093/emboj/20.6.1215. PMC 145528. PMID 11250888.

- ^ Koster MI (July 2009). “Making an epidermis”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1170 (1): 7–10. Bibcode: 2009NYASA1170....7K. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04363.x. PMC 2861991. PMID 19686098.

- ^ Halprin KM (January 1972). “Epidermal "turnover time"--a re-examination”. The British Journal of Dermatology 86 (1): 14–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1972.tb01886.x. PMID 4551262.

- ^ “Measurement of the transit time for cells through the epidermis and stratum corneum of the mouse and guinea-pig”. Cell and Tissue Kinetics 20 (5): 461–72. (September 1987). doi:10.1111/j.1365-2184.1987.tb01355.x. PMID 3450396.

- ^ “The skin: an indispensable barrier”. Experimental Dermatology 17 (12): 1063–72. (December 2008). doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00786.x. PMID 19043850.

- ^ “Intracellular calcium alterations in response to increased external calcium in normal and neoplastic keratinocytes”. Carcinogenesis 10 (4): 777–80. (April 1989). doi:10.1093/carcin/10.4.777. PMID 2702726.

- ^ “Role of intracellular-free calcium in the cornified envelope formation of keratinocytes: differences in the mode of action of extracellular calcium and 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3”. Journal of Cellular Physiology 146 (1): 94–100. (January 1991). doi:10.1002/jcp.1041460113. PMID 1990023.

- ^ Reiss, M; Lipsey, LR; Zhou, ZL (1991). “Extracellular calcium-dependent regulation of transmembrane calcium fluxes in murine keratinocytes”. Journal of Cellular Physiology 147 (2): 281–91. doi:10.1002/jcp.1041470213. PMID 1645742.

- ^ Mauro, TM; Pappone, PA; Isseroff, RR (1990). “Extracellular calcium affects the membrane currents of cultured human keratinocytes”. Journal of Cellular Physiology 143 (1): 13–20. doi:10.1002/jcp.1041430103. PMID 1690740.

- ^ Mauro, TM; Isseroff, RR; Lasarow, R; Pappone, PA (1993). “Ion channels are linked to differentiation in keratinocytes”. The Journal of Membrane Biology 132 (3): 201–9. doi:10.1007/BF00235738. PMID 7684087.

- ^ Tu, CL; Oda, Y; Bikle, DD (1999). “Effects of a calcium receptor activator on the cellular response to calcium in human keratinocytes”. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 113 (3): 340–5. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00698.x. PMID 10469331.

- ^ Hennings, Henry; Michael, Delores; Cheng, Christina; Steinert, Peter; Holbrook, Karen; Yuspa, Stuart H. (1980). “Calcium regulation of growth and differentiation of mouse epidermal cells in culture”. Cell 19 (1): 245–54. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(80)90406-7. PMID 6153576.

- ^ Su, MJ; Bikle, DD; Mancianti, ML; Pillai, S (1994). “1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 potentiates the keratinocyte response to calcium”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 269 (20): 14723–9. PMID 7910167.

- ^ Fu, G. K.; Lin, D; Zhang, MY; Bikle, DD; Shackleton, CH; Miller, WL; Portale, AA (1997). “Cloning of Human 25-Hydroxyvitamin D-1 -Hydroxylase and Mutations Causing Vitamin D-Dependent Rickets Type 1”. Molecular Endocrinology 11 (13): 1961–70. doi:10.1210/me.11.13.1961. PMID 9415400.

- ^ Kawakubo, Tomoyo; Yasukochi, Atsushi; Okamoto, Kuniaki; Okamoto, Yoshiko; Nakamura, Seiji; Yamamoto, Kenji (2011). “The role of cathepsin E in terminal differentiation of keratinocytes”. Biological Chemistry 392 (6): 571–85. doi:10.1515/BC.2011.060. hdl:2324/25561. PMID 21521076.

- ^ Jackson, B.; Brown, S. J.; Avilion, A. A.; O'Shaughnessy, R. F. L.; Sully, K.; Akinduro, O.; Murphy, M.; Cleary, M. L. et al. (2011). “TALE homeodomain proteins regulate site-specific terminal differentiation, LCE genes and epidermal barrier”. Journal of Cell Science 124 (10): 1681–1690. doi:10.1242/jcs.077552. PMC 3183491. PMID 21511732.

- ^ a b Rheinwald, JG; Green, H (1975). “Serial cultivation of strains of human epidermal keratinocytes: The formation of keratinizing colonies from single cells”. Cell 6 (3): 331–43. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(75)80001-8. PMID 1052771.

- ^ Truong, AB; Kretz, M; Ridky, TW; Kimmel, R; Khavari, PA (2006). “P63 regulates proliferation and differentiation of developmentally mature keratinocytes”. Genes & Development 20 (22): 3185–97. doi:10.1101/gad.1463206. PMC 1635152. PMID 17114587.

- ^ Fuchs, E; Green, H (1981). “Regulation of terminal differentiation of cultured human keratinocytes by vitamin A”. Cell 25 (3): 617–25. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(81)90169-0. PMID 6169442.

- ^ Rheinwald, JG; Green, H (1977). “Epidermal growth factor and the multiplication of cultured human epidermal keratinocytes”. Nature 265 (5593): 421–4. Bibcode: 1977Natur.265..421R. doi:10.1038/265421a0. PMID 299924.

- ^ Barrandon, Y; Green, H (1987). “Cell migration is essential for sustained growth of keratinocyte colonies: The roles of transforming growth factor-alpha and epidermal growth factor”. Cell 50 (7): 1131–7. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90179-6. PMID 3497724.

- ^ Brenner M; Hearing VJ. (May–June 2008). “The Protective Role of Melanin Against UV Damage in Human Skin”. Photochemistry and Photobiology 84 (3): 539–549. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00226.x. PMC 2671032. PMID 18435612.

- ^ Ito, M; Liu, Y; Yang, Z; Nguyen, J; Liang, F; Morris, RJ; Cotsarelis, G (2005). “Stem cells in the hair follicle bulge contribute to wound repair but not to homeostasis of the epidermis”. Nature Medicine 11 (12): 1351–4. doi:10.1038/nm1328. PMID 16288281.

- ^ Claudinot, S; Nicolas, M; Oshima, H; Rochat, A; Barrandon, Y (2005). “Long-term renewal of hair follicles from clonogenic multipotent stem cells”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (41): 14677–82. Bibcode: 2005PNAS..10214677C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507250102. PMC 1253596. PMID 16203973.

- ^ Ito, M; Yang, Z; Andl, T; Cui, C; Kim, N; Millar, SE; Cotsarelis, G (2007). “Wnt-dependent de novo hair follicle regeneration in adult mouse skin after wounding”. Nature 447 (7142): 316–20. Bibcode: 2007Natur.447..316I. doi:10.1038/nature05766. PMID 17507982.

- ^ Shen, Yue; Guo, Yongzhi; Du, Chun; Wilczynska, Malgorzata; Hellström, Sten; Ny, Tor (2012). “Mice deficient in urokinase-type plasminogen activator have delayed healing of tympanic membrane perforations”. PloS One 7 (12): e51303. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051303. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3517469. PMID 23236466.

- ^ Young AR (June 1987). “The sunburn cell”. Photodermatology 4 (3): 127–134. PMID 3317295.

- ^ “The sunburn cell revisited: an update on mechanistic aspects”. Photochemical and Photobiological Sciences 1 (6): 365–377. (June 2002). doi:10.1039/b108291d. PMID 12856704.

- ^ a b “Pleiotropic age-dependent effects of mitochondrial dysfunction on epidermal stem cells”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 (33): 10407–12. (August 2015). Bibcode: 2015PNAS..11210407V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1505675112. PMC 4547253. PMID 26240345.

- ^ Crissey, John Thorne; Parish, Lawrence C.; Holubar, Karl (2002). Historical Atlas of Dermatology and Dermatologists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 147. ISBN 1-84214-100-7

- ^ a b c Seema, Chhabra; Pranay, Tanwar; Kumar, AroraSandeep (2013). “Civatte bodies: A diagnostic clue”. Indian Journal of Dermatology 58 (4): 327. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.113974. ISSN 0019-5154. PMC 3726905. PMID 23919028.

関連文献

[編集]“Human lactoferrin stimulates skin keratinocyte function and wound re-epithelialization”. The British Journal of Dermatology 163 (1): 38–47. (July 2010). doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09748.x. PMID 20222924.