セルピン

| セルピン(セリンプロテアーゼインヒビター) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| 識別子 | |||||||||||

| 略号 | Serpin, SERPIN (root symbol of family) | ||||||||||

| Pfam | PF00079 | ||||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000215 | ||||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00256 | ||||||||||

| SCOP | 1hle | ||||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1hle | ||||||||||

| CDD | cd00172 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

セルピン(セリンプロテアーゼインヒビター、セリンプロテアーゼ阻害剤、英: Serpin)は、最初にプロテアーゼ阻害効果を持つ事で同定された類似構造を持つタンパク質のスーパーファミリーで、全ての界の生物で発見される[1]。セルピン (serpin) の略名は元々最初に同定されたセルピンがキモトリプシン様セリンプロテアーゼに対して働く (serine protease inhibitors) ために名付けられた造語である[2][3]。特筆すべきはセルピンの珍しい活性機構であり、セルピンは立体構造の大きな変化を受ける事でプロテアーゼの活性中心を破壊し、標的を不可逆的に阻害する[4][5]。この阻害機構は他の一般的なプロテアーゼ阻害剤が競合的阻害剤で、酵素と結合して活性中心を塞ぐ事で働くのと対照的である[5][6]。

セルピンによるプロテアーゼ阻害は血液凝固反応や炎症といった数々の生化学行程を制御するため、セルピンに含まれるタンパク質は医学研究の対象となる[7]。セルピンの構造変化はユニークであり、それゆえに構造生物学やタンパク質の折りたたみの解析においてもセルピンは興味深い研究対象とされる[4][5]。構造変化による阻害機構はいくつかの利点を持つが、同時に欠点も抱えており、タンパク質の折りたたみ異常や不活性の長鎖重合体の形成のようなセルピン病 (serpinopathy) を起因する変異に対し脆弱である[8][9]。セルピンの重合反応は活性を有する阻害剤の減少につながるのみならず、細胞死や臓器不全をも起こしうる[7]。

ほとんどのセルピンはタンパク質の分解反応を制御するが、中にはセルピンの構造を持ちながら酵素阻害剤として働かず、貯蔵(卵白中のオボアルブミンのように)や、ホルモンの輸送タンパク質(チロキシン結合グロブリンやトランスコルチン)のように運搬に関わったり、分子シャペロン(ヒートショックプロテイン47)として働くものもある[6]。以上のようなタンパク質は阻害剤として働かないにもかかわらず、進化学的に近縁なため、セルピンという語句はセリンプロテアーゼの阻害剤以外にも使われる[1]。

歴史

[編集]血漿のプロテアーゼ阻害効果は1800年代の終わりには既に報告されていたが[10]、1950年代以降までアンチトロンビンやα1-アンチトリプシンをはじめとしたセルピンは分離されていなかった[11]。セルピンに関する初期の研究はヒトの病気に焦点を当てていた。肺気腫を引き起こすアルファ1アンチトリプシン欠損症はもっとも一般的な遺伝性疾患の一つであり[8][12][13]、また、アンチトロンビンの欠損は血栓症の原因となる[14][15]。

1980年代にはこれらの阻害剤が、プロテアーゼ阻害剤(例: α1-アンチトリプシン)と非阻害剤(例: オボアルブミン)両者を含む、相同なタンパク質スーパーファミリーの一部である事が明らかになった[16]。"Serpin"の名は一般的なセルピンの効果であるセリンプロテアーゼ阻害剤 (serine protease inhibitors) に基づいた造語である[16]。同じ頃に、セルピンタンパク質は初めて立体構造が解かれ、まず弛緩型の、そして後に緊張型の構造が明らかにされた[17][18]。セルピンの構造解析はセルピンの阻害作用が立体構造の珍しい変化を伴う事を示し、その後のセルピンの研究は構造に焦点を当てたものになる[5][18]。

これまでに同定された1000種類以上のセルピンには、36種のヒトのタンパク質の他、動物、植物、菌類、細菌、古細菌といった全ての界のものが含まれ、ウイルスから同定されたものもある[19][20][21]。2000年代にはセルピンスーパーファミリーを進化学的な関係から分類するための命名体系が導入された[1]。このようにセルピンはプロテアーゼ阻害剤ではもっとも巨大でもっとも多様なスーパーファミリーを形成している[22]。

活性

[編集]

ほとんどのセルピンはプロテアーゼの阻害剤で、細胞外のキモトリプシン様セリンプロテアーゼを標的とする。これらのプロテアーゼは触媒三残基の内、求核的なセリン残基を活性部位に持っている。例としてトロンビンやトリプシン、ヒト好中球エラスターゼなどが挙げられよう[23]。セルピンはプロテアーゼの分解機構における中間体を捕らえることで、不可逆的に自殺型阻害剤として働く[24]。

セルピンの中にはセリンプロテアーゼ以外のプロテアーゼのクラスを(典型的にはシステインプロテアーゼ)阻害するものもあり、「クラス横断型阻害剤 (cross-class inhibitors) 」と呼ばれる。セリンプロテアーゼと違うのは活性部位にセリンではなく、求核的なシステイン残基を用いる点にある[25]。標的の違いにもかかわらず、酵素化学的に両者は似ており、両クラスのプロテアーゼに対するセルピンの阻害機構は同一である[26]。クラス横断型阻害剤の例として扁平上皮癌抗原1 (SCCA-1) としても知られるセルピンB4やトリのセルピンであるMENTなどがあり、この2つはいずれもパパイン様システインプロテアーゼを阻害する[27][28][29]。

生物学的機能と局在

[編集]プロテアーゼの阻害

[編集]ヒトのセルピンのおおよそ3分の2は細胞外で働き、血中においてプロテアーゼの機能を阻害してプロテアーゼの活性を穏やかにする。例えば細胞外セルピンは血液凝固(アンチトロンビン)、炎症・免疫反応(アンチトリプシン、アンチキモトリプシン、C1阻害因子)、組織修復(PAI-1)におけるタンパク質分解カスケードを制御する[6]。シグナルカスケードプロテアーゼを阻害することで、セルピンは発生にも影響を与える[30][31]。ヒトのセルピンの表(下記)はヒトのセルピンの広範な役割や、セルピンの欠損に起因する疾患を示す。

細胞内で阻害効果をもつセルピンは多くの場合、複数の役割を持っているようであり、標的を同定するのは困難であった。さらに、ヒトのセルピンの多くはマウスのような実験動物において適切で機能的な相同分子が存在しない。それでも、細胞内セルピンの重要な役割は細胞内におけるプロテアーゼの不適切な活性を防止することかもしれない[32]。例えば研究が進んでいるヒトの細胞内セルピンの一つがセルピンB9であり、これは細胞毒性を持つ顆粒プロテアーゼ、グランザイムBを阻害する。そうすることでセルピンB9は不慮のグランザイムB9の放出や、時期尚早もしくは望まれない細胞死の経路の活性化を防いでいる可能性がある[33]。

ウイルスの中にはセルピンを用いて宿主のプロテアーゼの機能を妨害するものもある。牛痘ウイルスのセルピン、CrmA(cytokine response modifier A)は感染した宿主細胞が炎症反応やアポトーシスを起こすのを避けるために用いられる。CrmAはシステインプロテアーゼであるカスパーゼ1によるIL-1やIL-18の切断を阻害する事で宿主の炎症反応を抑制し、感染性を増大する[34]。真核生物では植物性のある種のセルピンがメタカスパーゼ[35]とパパイン様システインプロテアーゼの両者を阻害する[36]。

非阻害的効果

[編集]非阻害的な細胞外セルピンもまた広範かつ重要な役割を持つ。チロキシン結合グロブリンとトランスコルチンはそれぞれチロキシン、コルチゾールを運搬する[37][38]。非阻害性セルピンであるオボアルブミンは卵白で最も豊富なタンパク質である。オボアルブミンの詳細な機能は知られていないが、胚発生における貯蔵タンパク質と考えられている[39]。ヒートショックタンパク質47はシャペロンでコラーゲンの適切な折りたたみに必須である。このヒートショックタンパク質はコラーゲン折りたたみが行われる小胞体において、コラーゲンの三重らせんを安定化させる働きを持つ[40]。

一部のセルピンはプロテアーゼ阻害機能とそれ以外の機能の両方を持つ。例えば核内システインプロテアーゼ阻害剤であるMENTは、鳥類において赤血球内のクロマチン再構成分子としても働く[28][41]。

構造

[編集]

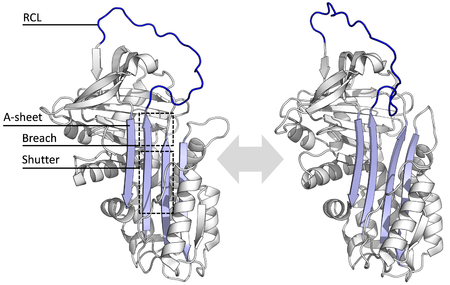

機能が多様であるにもかかわらず、全てのセルピンは構造(あるいは折りたたみ)を共有する。典型的には3つのβシート(それぞれA、B、Cと呼ばれる)と8か9個のαヘリックス(hAからhIまで)を持つ[17][18]。セルピンの機能においてもっとも重要なのはAシートと反応中心ループ (reactive centre loop, RCL) である。Aシートは'shutter'と呼ばれる領域とその上部にある'breach'と呼ばれる領域を持つ、平行な2つのβストランドを含む。RCLは標的となるプロテアーゼとの初期相互作用を形成する。セルピンの構造が解かれた事で、RCLは完全に露出しているか部分的にAシートに取り込まれていると示され、また、セルピンはこの2つの構造の間で動的平衡をとっていると考えられている[5]。また、RCLはセルピンの他の部位とは一過性の相互作用しか形成しないため、柔軟性が高く、溶媒に露出している[5]。

これまでに決定されてきたセルピンの構造はいくつかの異なった立体構造を含み、このことはセルピンの多段階反応をによる活性を理解するために必要である。そのため、構造生物学はセルピンの機能と性状を理解する上で中心的な役割を担ってきている[5]。

立体構造の変化と阻害機構

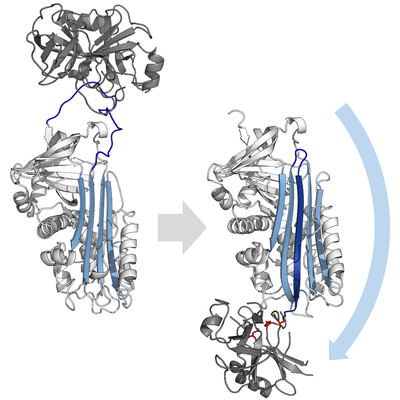

[編集]阻害型のセルピンは多くの小分子型の阻害剤(例: Kunitz型阻害剤)と違い、鍵と鍵穴の関係に例えられる典型的な競合作用によって標的となるプロテアーゼを阻害する訳ではない。セルピンは競合作用の代わりに珍しい立体構造変化を用い、それによりプロテアーゼの構造を破壊して触媒作用を停止する。立体構造の変化によってRCLはタンパク質分子の反対側へ移動し、シートAへ組み込まれ、追加の逆平行βストランドを形成する。この構造変化によりセルピンは緊張状態 (S) から、熱力学的に安定な弛緩状態 (R) へと転換する(S-R遷移)[4][5][44]。

セリンプロテアーゼやシステインプロテアーゼは二段階の行程を踏んでペプチド結合の切断を触媒する。最初に活性部位の三残基の触媒残基が基質のペプチド結合に対して求核攻撃を行う。これにより新たにN末端が露出し、酵素と基質の間に共有結合性のエステル結合が形成される[4]。この共有結合性の酵素基質複合体をアシル-酵素中間体(acyl-enzyme intermediate、アシル酵素複合体とも[45])と呼ぶ。通常の基質の場合、このエステル結合は加水分解され、新たにC末端が露出して触媒反応が終了する。しかし、セルピンがプロテアーゼによって切断された場合、セルピンはアシル-酵素中間体が加水分解される前に急速にS-R遷移を受ける。立体構造変化の相対的反応速度がプロテアーゼによる加水分解に比べ10の数乗速いという事実によって阻害の効率が決定される[4]。

この段階においてもRCLはプロテアーゼとエステル結合を通して共有結合性にくっついているため、S-R遷移はプロテアーゼをセルピン分子の上から下へ(下図参照)と移動させ、触媒三残基をねじ曲げる。ねじ曲げられたプロテアーゼはアシル酵素中間体を極めて低速にしか加水分解できず、そのためプロテアーゼは数日から数週間に渡りセルピン分子に共有結合性にくっついたままになる[24]。セルピンはこのように一分子のセルピンが一分子のプロテアーゼを永続的に不活化し、一度しか機能しないため、非可逆的阻害剤かつ自殺型阻害剤に分類される[4][45]。

アロステリック活性化

[編集]

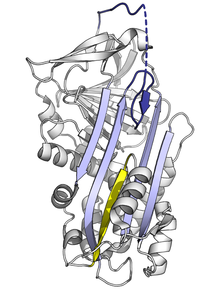

セルピンの立体構造変化は静的な"鍵と鍵穴"型(競合阻害型)のプロテアーゼ阻害剤に対する重要な利点を与える[46]。さらに、阻害剤型のセルピンの機能は、特異的な補因子とのアロステリックな相互作用によって制御されることがある。アンチトロンビン、ヘパリン補因子II、MENT、およびマウスアンチキモトリプシンのX線結晶構造により、これらのセルピンではRCLの最初の2つのアミノ酸がAシートの頂上部に取り込まれるような立体構造が採用されることが明らかになった。このような、RCLが部分的に本体に取り込まれた立体構造は機能的に重要であり、以上の様なセルピンは補因子と結合すると取り込まれた部位を露出させる様な、プロテアーゼと反応しやすい立体構造への構造の再構成を行う[47][48]。この立体構造の再構成によりセルピンはより効率的な阻害剤となっている。

補因子による活性化を受けるセルピンの典型的な例はアンチトロンビンであり、この分子は部分的に取り込まれた、相対的に不活性な状態で血漿中を循環している。主要特異性決定基(P1アルギニン)はセルピン分子の本体へ向いているため、プロテアーゼが利用できない。高分子であるヘパリンの内部にある高い親和性を持つペンタサッカライド(五糖)の配列がセルピンに結合すると、アンチトロンビンの立体構造が変化、RCLが反転、P1アルギニンの露出する。こうしてヘパリンのペンタサッカライドと結合したアンチトロンビンはトロンビンと第Xa因子のより効果的な阻害剤となる[49][50][51]。さらに、この2つの凝固因子系プロテアーゼ、トロンビンと第Xa因子もまたヘパリンとの結合部位(エキソサイトと呼ばれる)を持つ。そのためヘパリンはプロテアーゼともセルピンとも結合し、両分子の相互作用を劇的に加速する。初期の相互作用の後、セルピンの最終的な複合体の形成が完了し、ヘパリンの部分は放出される。この相互作用は生理的に重要な役割を持つ。例えば、血管壁が損傷を受けると、ヘパリンが露出し、アンチトロンビンが活性化して凝固反応を制御する。この相互作用の分子的原理の理解により、抗凝固薬として使われる合成ヘパリンペンタサッカライドであるフォンダパリヌクスが開発された[52][53]。

潜在型の立体構造

[編集]

あるセルピンはプロテアーゼによる切断なしに自然とS-R遷移を行い、潜在型と呼ばれる立体構造をとる。潜在型のセルピンはプロテアーゼと相互作用できず、それ故もはやプロテアーゼ阻害剤として働かない。潜在型への立体構造の変化は、セルピンの切断によって起きるS-R遷移とは異なる。RCLは無傷なため、RCLが完全に組み込まれるためにはCシートの最初のストランドが剥がれなければならない[54]。

潜在型への遷移の調節はPAI-1のようなある種のセルピンの制御機構として働く。PAI-1は阻害剤として働くS型構造として産生されるが、PAI-1は補因子であるビトロネクチンと結合しない限り、潜在型へ移行する事で自動的に不活化される[54]。同様に、アンチトロンビンもまた、ヘパリンによるアロステリック調節以外の予備の調節機構として自然と潜在型へ移行する事がある[55]。また、サーモアナエロバクター属の細菌が持つセルピンであるテングピンのN末端は、テングピンの活性型構造を維持するために必要である。N末端領域による相互作用を遮断することで、このセルピンは自然と潜在型構造へ立体構造を変化させる[56][57]。

非阻害的機能における立体構造の変化

[編集]ある種の非阻害剤型セルピンも立体構造を変化させることでその機能を果たす。例えば、チロキシン結合グロブリンの天然状態であるS型はチロキシンに対し高い親和性を持つが、切断を受けたR型は親和性が低い。同様にトランスコルチンも切断後のR型より天然状態のS型の方がコンチゾールに対する親和性が高い。このようにして、上記のセルピンにおいてはRCLの切断とS-R遷移がプロテアーゼの阻害ではなくリガンドの放出に利用される[37][38][58]。

セルピンの中にはS-R遷移が細胞のシグナル伝達を活性化するものもある。この場合、標的プロテアーゼと複合体を形成したセルピン分子が受容体によって認識される。そしてこのセルピン-プロテアーゼ複合体と受容体の結合が、受容体による下流シグナルへと繋がるのである[59]。そのためS-R遷移は細胞にプロテアーゼ活性の存在を警告するために使われる[59]。この事はセルピンが単純にシグナルカスケードに関与するプロテアーゼに影響を与える通常の方法と異なる[30][31]。

分解

[編集]セルピンが標的プロテアーゼを阻害すると、セルピンは永続的に複合体を形成するが、この複合体は後始末を受ける必要がある。細胞外セルピンの場合、最終産物であるセルピン-酵素複合体は循環系から迅速に廃棄される。哺乳類においてこの迅速な除去を行う機構の一つは低密度リポタンパク質受容体関連タンパク質 (LPR) を介したもので、このタンパク質はアンチトロンビン、PAI-1、ニューロセルピン等のセルピンによって形成される複合体と結合し、食作用を誘導する[59][60]。同様にショウジョウバエのセルピン、ネクロティック (Necrotic) はリポホリン受容体1(哺乳類のLDL受容体ファミリーの相同分子)によって細胞内に運ばれた後、ライソゾーム内で分解される[61]。

疾患とセルピン病

[編集]セルピンは広範な生理機能に関与しているため、セルピン分子をコードする遺伝子における変異は様々な疾患の原因となる。セルピンの活性や特異性、凝集特性を変化させるような変異は必ずセルピンの働きに影響する。最も多く認められるセルピン関連疾患はセルピンが多量体を形成して凝集することによるものだが、他にも疾患に結びつく変異がいくつかある[5][62]。αアンチトリプシン欠損症は特に多い遺伝性疾患である[8][13]。

不活性や欠損

[編集]

堅く折りたたまれたセルピンは高エネルギー状態にあるため、変異はセルピンが正しく阻害作用を示す前に、セルピンの立体構造を容易に低エネルギーの立体構造(弛緩型構造や潜在型構造)へと変化させてしまう[7]。

RCLのAシートへの取り込み頻度や範囲に影響する変異は、セルピンがプロテアーゼと接触する前に立体構造のS-R遷移を起こす原因となる。セルピン分子はこの立体構造の変化を一度しか行えないため、結果として生じる不発のセルピン分子は不活性となり、標的プロテアーゼを適切に制御することができなくなる[7][63]。同様に、単量体の潜在型構造への不適切な遷移を促進する変異も、活性化セルピンの量を減らすため疾患の原因となり得る。例えばアンチトロンビンの疾患関連多型であるwibble型やwobble型[64]は両者とも潜在型構造の形成を促進する。

アンチトリプシンの疾患関連変異 (L55P) は上記以外の不活性構造、「δ型立体構造」の存在を明らかにした。δ型立体構造においてはRCLの4つのアミノ酸が、シートAの頂上部へ取り込まれる。シートAの下部はαヘリックスの一つ、Fヘリックスが部分的にβストランドへ構造変化を起こすことで埋められ、βシートの水素結合を補完する[65]。アンチトリプシン以外のセルピンがこの異性体型をとることができるか、またδ型構造が機能的役割をもつかどうかは明らかでないが、チロキシン結合グロブリンはチロキシンの放出時にδ型構造をとる可能性があると推測されている[38]。非阻害剤型セルピンが変異を起こした場合も疾患の原因となりうる。例えばSERPINF1の変異はヒトのIV型骨形成不全症の原因となる[66]。

本来必要なセルピンが無い場合、通常抑制されているプロテアーゼが過剰に活性化し、セルピン病(セルピノパシー)へと移行する[7]。従ってセルピンの単純な欠損(例:欠損変異)は疾患を生じる[67]。マウスにおいては、セルピンが無い場合の影響からセルピンの通常の機能を実験的に決定するために、遺伝子ノックアウトが用いられる[68]。

特異性の変化

[編集]稀にセルピンのRCL内部における1アミノ酸の変化により、セルピンの特異性が変化して、間違ったプロテアーゼを標的としてしまう事がある。例えばアンチトリプシン-ピッツバーグ変異 (M358R) はα1アンチトリプシンの標的をトリプシンからトロンビンに変えてしまい、出血性疾患の原因となる[69]。

多量体化と凝集

[編集]ほとんどのセルピン疾患はタンパク質の凝集によるもので、「セルピン病」と呼ばれる[9][65]。本質的に不安的な構造のため、セルピンは折りたたみ異常を促進する疾患起因変異に対し脆弱である[65]。よく研究されているセルピン病に、家族性の肺気腫や時に肝硬変を引き起こすα1アンチトリプシン欠損症、アンチトロンビン欠損症関連の家族性血栓症、C1阻害剤欠損症による1型および2型の遺伝性血管性浮腫 (HAE)、およびニューロセルピンの封入対形成を伴う家族性脳症(FENIB; ニューロセルピンの多量体形成に起因する稀な認知症)などが含まれる[8][9][70][71]。

セルピン単量体の凝集は不活性の弛緩型立体構造(RCLがAシートに取り込まれた状態)をとる。それゆえ多量体は温度に対し極めて安定で、プロテアーゼを阻害できない。そのためセルピン病は2つの主要原理によって他のタンパク質病(プロテオパチー、例:プリオン病)と似た病理を示す[8][9]。まず、活性化セルピンの欠失はプロテアーゼの暴走と組織破壊を起こす。次に、超安定多量体自身もセルピンを代謝する小胞体を妨害し、結果的に細胞死と組織損傷を起こす。アンチトリプシン欠損症ではアンチトリプシンの多量体が肝細胞の細胞死を引き起こし、肝臓の破壊と肝硬変の原因となる。細胞内でセルピン多量体は小胞体における分解を受けて徐々に除去される[72]。しかし、セルピン多量体が細胞死を起こす詳細な機構はいまだ完全には理解されていない[8]。

セルピン多量体は、生理的にはドメイン交換現象によって生じると考えられている。この現象においてはセルピン分子の一部分が他のセルピン分子に取り込まれる[73]。ドメイン交換は変異や環境因子がセルピンが天然状態の構造へと折りたたまれる行程における最終段階を妨害し、高エネルギー中間体の折りたたみ異常を起こす事で発生する[74]。これまでに二量体と三量体の両者についてドメイン交換構造が解かれてきた。まず、(アンチトロンビンの)二量体においてはRCLとAシートの一部が他方のセルピン分子に組み込まれる[73]。一方、(アンチトリプシンの)ドメイン交換型三量体は二量体とは全く異なり、Bシートの交換によって多量体が形成され、各分子中のRCLは自身のAシートに取り込まれる[75]。また、セルピンがRCLを他方のAシートに挿入することでドメイン交換構造を形成する可能性(Aシート多量体化)も提案されている[70][76]。以上のようなドメイン交換により生じる二量体構造や三量体構造は疾患関連多量体凝集の塊を作ると考えられているが、正確な原理は未だ明らかでない[73][74][75][77]。

治療戦略

[編集]最も普遍的なセルピン病、アンチトリプシン欠損症の治療のために、いくつかの治療方針が実用、あるいは研究されている[8]。アンチトリプシン増強療法は重度のアンチトリプシン欠損症関連肺気腫に適用される[78]。最初にProlastinとして市販されたこの治療薬は、アンチトリプシンをドナーの血漿から精製したもので、経静脈投与により使用される[8][79]。また、重度のアンチトリプシン関連疾患においては肺と肝臓の移植が効果的であると証明されている[8][80]。動物実験ではiPS細胞に対する遺伝子療法がアンチトリプシン多量体形成による欠乏を改善し、肝臓による活性アンチトリプシンの産生能を回復する事に成功している[81]。他にin vitroでアンチトリプシン多量体形成を遮断する小分子の開発が行われている[82][83]。

進化

[編集]セルピンはプロテアーゼ阻害剤の中で最も普遍的でかつ最大のスーパーファミリーである[1][22]。最初は真核生物のみが持つものと信じられていたが、後に細菌、古細菌、さらにある種のウイルスからも発見されている[19][20][84]。ただし、原核生物のセルピン遺伝子が祖先から受け継がれたものか、それとも真核生物から水平伝播によって獲得されたものなのかは明らかでない。植物性のものも動物性のものも、ほとんどの細胞内セルピンは系統学的に単一クレードに属することから、細胞内セルピンと細胞外セルピンは植物と動物の分岐の後に分化した可能性がある[85]。例外の一つに細胞内ヒートショックタンパク質であるHSP47があり、この分子はコラーゲンの適切な折りたたみに必須のシャペロンで、シス-ゴルジ体と小胞体間を循環する[40]。

プロテアーゼ阻害作用は古来から伝わる機能で、非阻害型のセルピンは進化学的な新機能獲得の結果と考えられている。S-R立体構造遷移は結合型セルピンの標的に対する親和性を調節するように適合した[38]。

分布

[編集]動物のセルピン

[編集]哺乳類

[編集]ヒト

[編集]ヒトのゲノムは16のセルピン分子のクレードをコードし、それぞれserpinAからserpinPまでの命名がされている16のクレードは29個の阻害型セルピンと7個の非阻害型セルピンを含む[6][68]。ヒトのセルピンは2001年から500個のセルピンの系統解析に基づいた命名系を持ち、例えばserpinXYというタンパク質はXクレードでY番目に命名されたタンパク質である事を意味する[1][19][68]。ヒトのセルピンの機能は生化学的研究、ヒトの遺伝性疾患、およびノックアウトマウスの実験系の知見を統合することで決定された[68]。

| 遺伝子名 | 一般名 | 局在 | 機能 / 活性[6][68] | 欠損動物の表現型[6][68] | ヒトの関連疾患 | 染色体上の位置 | タンパク質構造 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERPINA1 | α1アンチトリプシン | 細胞外 | ヒト好中球エラスターゼの阻害剤[86]。切断を受けたSERPINA1のC末端断片はHIV-1の感染を防ぐかもしれない[87]。 | 欠損は肺気腫を、多量体形成は肝硬変を引き起こす(セルピン病)[8][88]。 | 14q32.1 | 1QLP, 7API, 1D5S | |

| SERPINA2 | アンチトリプシン関連タンパク質 | 細胞外 | 偽遺伝子の可能性あり[89]。 | 14q32.1 | |||

| SERPINA3 | α1アンチキモトリプシン | 細胞外 | カテプシンGの阻害剤[90]。肝細胞においては染色体凝縮の役割も[91]。 | 調節異常はアルツハイマー病の原因(セルピン病)[92]。 | 14q32.1 | 1YXA, 2ACH | |

| SERPINA4 | キリスタチン | 細胞外 | カリクレイン阻害剤で血管の機能を調節[93][94]。 | 高血圧ラットにおける欠損は腎臓や心血管系の損傷を悪化させる[95]。 | 14q32.1 | ||

| SERPINA5 | プロテインC阻害剤 | 細胞外 | 活性化プロテインCの阻害剤[96]。細胞内で細菌の食作用を防止する役割[97]。 | オスのマウスでのノックアウトは不妊を起因する[98]。多発性硬化症においては慢性活動性脱髄巣内に集積[99]。 | 14q32.1 | 2OL2, 3B9F | |

| SERPINA6 | トランスコルチン | 細胞外 | 非阻害剤。コルチゾールと結合[37]。 | 欠損は慢性疲労と関連[100]。 | 14q32.1 | 2V6D, 2VDX, 2VDY | |

| SERPINA7 | チロキシン結合グロブリン | 細胞外 | 非阻害剤。チロキシンと結合[38]。 | 欠損は低チロキシン症の原因[101][102]。 | Xq22.2 | 2CEO, 2RIV, 2RIW | |

| SERPINA8 | アンギオテンシノーゲン | 細胞外 | 非阻害剤で、レニンよって切断される事でアンギオテンシンIを生じる[103]。 | マウスのノックアウトは低血圧を生じる[104]。 | 変異は低血圧と関連[105][106][107]。 | 1q42-q43 | 2X0B, 2WXW, 2WXX, 2WXY, 2WXZ, 2WY0, 2WY1 |

| SERPINA9 | センテリン / GCET1 | 細胞外 | 阻害剤でナイーブB細胞を管理[108][109]。 | 多くのB細胞性リンパ腫で発現量増加[110][111]。 | 14q32.1 | ||

| SERPINA10 | プロテインZ関連プロテイナーゼ阻害剤 | 細胞外 | プロテインZと結合して第Xa因子と第XI因子を不活化[112]。 | 14q32.1 | 3F1S, 3H5C | ||

| SERPINA11 | – | おそらく細胞外 | 不明 | 14q32.13 | |||

| SERPINA12 | バスピン | 細胞外 | カリクレイン7の阻害剤。インシュリン感作性アディポサイトカイン[113]。 | 血漿中の高濃度バスピンは2型糖尿病と関連[114]。 | 14q32.1 | 4IF8 | |

| SERPINA13 | – | おそらく細胞外 | 不明 | 14q32 | |||

| SERPINB1 | 単球好中球エラスターゼ阻害剤 | 細胞内 | 好中球エラスターゼの阻害剤[115]。 | マウスでのノックアウトは好中球の生存率低下と免疫不全を起因する[116]。 | 6p25 | 1HLE | |

| SERPINB2 | プラスミノーゲン活性化因子阻害剤 | 細胞内 / 細胞外 | 細胞外uPA の阻害剤。細胞内の機能は不明だがウイルス感染を防ぐ可能性がある[117]。 | マウスでの欠損により線虫に体する免疫応答が低下[118]。マウスでのノックアウトは何の表現型も示さない[119]。 | 18q21.3 | 1BY7 | |

| SERPINB3 | SCCA-1 | 細胞内 | パパイン様システインプロテアーゼ[27]とカテプシンK、L、S[120][121]の阻害剤。 | マウスにおけるSerpinb3a(ヒトのSERPINB3およびSERPINB4両者のホモログ)の欠損は、気管支喘息の実験モデルで粘液産生を減少させる[122] | 18q21.3 | 2ZV6 | |

| SERPINB4 | SCCA-2 | 細胞内 | キモトリプシン様セリンプロテアーゼであるカテプシンGおよびキマーゼの阻害剤[121][123]。 | マウスにおけるSerpinb3a(ヒトのSERPINB3およびSERPINB4両者のホモログ)の欠損は、気管支喘息の実験モデルで粘液産生を減少させる[122] | 18q21.3 | ||

| SERPINB5 | マスピン | 細胞内 | 非阻害剤、機能不明[124][125][126] (マスピンも参照)。 | 当初マウスでのノックアウトは致死性と報告されたが[127]、その後何の表現型も示さない事が示された[126]。マスピンの発現は近傍のがん抑制遺伝子(脱リン酸化酵素PHLPP1)の発現を反映する予後指標になるかもしれない[126]。 | 18q21.3 | 1WZ9 | |

| SERPINB6 | PI-6 | 細胞内 | カテプシンGの阻害剤[128]。 | マウスでのノックアウトは聴覚喪失[129]および軽度の好中球減少症を起因[130]。 | 欠損は聴覚欠損と関連[131]。 | 6p25 | |

| SERPINB7 | メグシン | 細胞内 | 巨核球の成熟に関与[132]。 | マウスでの過剰発現は腎臓病を起因[133]。マウスでのノックアウトは組織学的な異常を来さない[133]。 | 変異は長島型掌蹠角皮症と関連[134]。 | 18q21.3 | |

| SERPINB8 | PI-8 | 細胞内 | フーリンの阻害剤かもしれない[135]。 | 18q21.3 | |||

| SERPINB9 | PI-9 | 細胞内 | 細胞毒性顆粒プロテアーゼであるグランザイムBの阻害剤[136]。 | マウスでのノックアウトは免疫不全を起因[137][138]。 | 6p25 | ||

| SERPINB10 | ボマピン | 細胞内 | 不明[139] | マウスでのノックアウトは何の表現型も示さない(C57/BL6; 実験動物 BC069938)。 | 18q21.3 | ||

| SERPINB11 | 細胞内 | 不明[140] | ネズミのSerpinb11は活性を持つ阻害剤だがヒトの相同分子は不活性である[140]。ポニーでの欠損は蹄壁分離病と関連[141]。 | 18q21.3 | |||

| SERPINB12 | ユコピン | 細胞内 | 不明[142] | 18q21.3 | |||

| SERPINB13 | フルピン/ ヘッドピン | 細胞内 | パパイン様システインプロテアーゼの阻害剤[143]。 | 18q21.3 | |||

| SERPINC1 | アンチトロンビン | 細胞外 | 凝固因子の阻害剤で、特に第X因子、第IX因子、およびトロンピンに対して働く[46]。 | マウスでのノックアウトは致死性[144]。 | 欠損により血栓症や他の凝固異常に(セルピン病)[15][145]。 | 1q23-q21 | 2ANT, 2ZNH, 1AZX, 1TB6, 2GD4, 1T1F |

| SERPIND1 | ヘパリン補因子II | 細胞外 | トロンビンの阻害剤[146]。 | マウスでのノックアウトは致死性[147]。 | 22q11 | 1JMJ, 1JMO | |

| SERPINE1 | プラスミノーゲン活性化因子阻害剤1 | 細胞外 | トロンビン、uPA、TPaの阻害剤[148]。 | 7q21.3-q22 | 1DVN, 1OC0 | ||

| SERPINE2 | グリア由来ネキシン / プロテアーゼネキシンI | 細胞外 | uPA、TPaの阻害剤[149]。 | 異常発現によりオスの不妊に繋がる[150]。ノックアウトはてんかんを起因[151] | 2q33-q35 | 4DY0 | |

| SERPINF1 | PEDF | 細胞外 | 非阻害剤、血管新生阻害分子の可能性あり[152]。PEDFはグリコサミノグリカンであるヒアルロナンと結合する事が報告されている[153]。 | マウスでのノックアウトは血管系や、膵臓と前立腺の質量に影響[152]。成体におけるNotch依存的脳室神経幹細胞による神経新生を促進[154]。ヒトでの変異はVI型骨形成不全症を起こす[66]。 | 17p13.3 | 1IMV | |

| SERPINF2 | α2アンチプラスミン | 細胞外 | プラスミン阻害剤で線維素溶解を阻害[155]。 | マウスでのノックアウトは線維素溶解を増強するが、繁殖障害は示さない[156]。 | 欠損により稀な出血異常を起こす[157][158]。 | 17pter-p12 | 2R9Y |

| SERPING1 | C1阻害剤 | 細胞外 | C1エラスターゼの阻害剤[159]。 | 特定の変異が加齢黄斑変性[160]や遺伝性血管性浮腫[161]と関連。 | 11q11-q13.1 | 2OAY | |

| SERPINH1 | HSP47 | 細胞内 | 非阻害剤、コラーゲンの折りたたみにおける分子シャペロン[40]。 | マウスでのノックアウトは致死性[162]。 | ヒトでの変異は重度の骨形成不全症を起因[163][164]。 | 11p15 | 4AXY |

| SERPINI1 | ニューロセルピン | 細胞外 | tPA、uPA、およびプラスミンの阻害剤[165]。 | 変異はFENIB認知症を起因(セルピン病)[166][167]。 | 3q26 | 1JJO, 3FGQ, 3F5N, 3F02 | |

| SERPINI2 | パンクピン | 細胞外 | 不明[168] | マウスでの欠損は腺房中心細胞の減少を通じた膵臓の機能不全を起因[169]。 | 3q26 |

特定の哺乳類のセルピン

[編集]哺乳類のセルピンの多くは、ヒトのセルピンと何の相同性も持たない事が明らかにされてきた。多数の齧歯類のセルピン(特にネズミが持つ細胞内セルピン一部)や子宮セルピンが例として挙げられよう。子宮セルピンはSERPINA14遺伝子によってコードされるAクレードに属するセルピンである。子宮セルピンはローラシアテリアの哺乳類の内、一部の動物種の子宮内膜がプロゲステロンないしエストロゲンの影響下で産生する[170]。おそらく、子宮セルピンは機能的なプロテアーゼ阻害剤ではなく、妊娠期の胚、胎児に対する母体の免疫応答を阻害したり、胎盤を介した輸送に関与したりする機能を持っているのだろう[171]。

昆虫

[編集]キイロショウジョウバエのゲノムは29のセルピン遺伝子を持つ。アミノ酸配列の解析から14のセルピンがクレードQに、3つがクレードKに分類されているが、残りの12は孤立しており、特定のクレードに分類されていない[172]。クレード分類体系をショウジョウバエのセルピンに対して用いるのは難しく、代わりにショウジョウバエの染色体上の位置に基づく、専門的な命名体系が適用されている。ショウジョウバエのセルピン遺伝子のうち13はゲノム上に孤立して存在している(Serpin-27Aを含む。下記参照。)。一方で残りの16は5つのクラスターを形成し、それぞれ染色体28D(2個)、42D(5個)、43A(4個)、77B(3個)、88E(2個)上に位置する[172][173][174]。

ショウジョウバエセルピンの研究によりSerpin-27AがEasterプロテアーゼ(タンパク質分解カスケードの最終段階を担う)を阻害し、背腹軸形成を制御する事が明らかになった。EasterプロテアーゼはSpätzle(ケモカイン型リガンド)を切断する機能を持ち、Spätzleの切断はtoll依存性のシグナル伝達に繋がる。パターン形成における中心的な役割と共に、tollのシグナル伝達系は昆虫の自然免疫応答においても重要である。よってserpin-A27は昆虫の免疫応答を制御する機能も持つ[31][175][176]。巨大な甲虫であるTenebrio molitorにおいてはあるタンパク質 (SPN93) が、セルピン全体をドメインとする構造を二重に持ち、tollのタンパク質分解カスケードを調節している[177]。

線虫

[編集]線虫の一種、C. elegansのゲノムはセルピンを9つ持ち、全てがシグナル配列を欠くため細胞内タンパク質のようである[178]。しかし、9つの内、プロテアーゼ阻害剤として働くのはわずか5つのであろう[178]。プロテアーゼ阻害機能を持つセルピンの一つ、SPR-6は防御機能を持ち、ストレス性のカルパイン関連リソソーム崩壊から虫体を守る。さらにSRP-6は破裂したリソソームから放出されるシステインプロテアーゼを阻害する。そのため、SRP-6欠損線虫はストレスに対して感受性である。SRP-6の欠損線虫が水中で死んでしまう(低浸透圧ストレス致死性表現型)点は特に重要である。そのためリソソームが細胞の運命を決定する上で一般的で制御可能な役割を持つと言われてきている[179]。

植物のセルピン

[編集]植物のセルピンは哺乳類のキモトリプシン様セリンプロテアーゼをin vitroで阻害できる事があり、大麦セルピンZx (BSZx) がその代表例である。このタンパク質はヒトのトリプシン、キモトリプシン、そして数種の凝固因子を阻害する事ができる[180]。しかしながらキモトリプシン様セリンプロテアーゼに近縁なタンパク質は植物に存在しない。小麦やライ麦のセルピンのRCLは胚乳のプロラミン貯蔵タンパク質で見られるようなポリQの繰り返し配列を含む[181][182]。そのため植物のセルピンは、貯蔵タンパク質を消化してしまう、昆虫や微生物のプロテアーゼを阻害する働きを持つ可能性が指摘されている。この仮説を支持する知見として、独特な植物セルピンがカボチャ (CmPS-1) [183]とキュウリの師管液から同定された[184][185]。CmPS-1の発現量増加とアブラムシの生存率の間には負の相関が観察されるが、試験管内で給餌する実験系においては組換えCmPS-1は昆虫の生存に影響しないようである[183]。

植物セルピンの他の役割と標的プロテアーゼも提案されてきた。シロイヌナズナ属のセルピン、AtSerpin1 (At1g47710; 3LE2) はパパイン様システインプロテアーゼである'Responsive to Desiccation-21' (RD21) を標的とすることでプログラム細胞死における設定値の調節を行っている[36][186]。AtSerpin1はまたin vitroでメタカスパーゼ様プロテアーゼに対しても阻害効果を持つ[35]。他にもAtSRP2 (At2g14540) とAtSRP3 (At1g64030) がDNA損傷への応答に関わるようである[187]。

真菌のセルピン

[編集]これまでに機能が明らかにされた真菌のセルピンは一つのみである。ネオカリマスティクス科Piromyces spp. E2株から発見されたセルピン (celpin) である。Piromycesは反芻動物の腸に生息する、植物の代謝に重要な嫌気性真菌の属名である。セルピン (celpin) は阻害機能を持ち、セルピンの構造の他にさらにN末端にドックリンドメインを2つを持つと予想される。ドックリンは、セルロースを分解する巨大細胞外タンパク質複合体である、真菌のセルロソームに内在するタンパク質が普遍的に持つ構造である[21]。そのためセルピン (celpin) はセルロソームを植物のプロテアーゼから保護していると考えられている。ある種の細菌のセルピンも同様にセルロソームに内在している[188]。

原核生物のセルピン

[編集]予想セルピン遺伝子は原核生物の種の間で散発的に分布している。In vitroの研究は原核生物のセルピンがプロテアーゼを阻害できる事を明らかにしており、これらの分子がin vivoでも同様の機能を持つことを示唆している。原核生物のセルピンは極限環境微生物からも発見されている。哺乳類のセルピンと対照的に、極限環境微生物から同定されるセルピンは熱分解に高い抵抗性を示す[189][190]。細菌のセルピンの正確な役割は未だ不明だが、Clostridium thermocellumのセルピンはセルロソーム内に存在する。セルロソーム関連セルピンに関してはセルロソームを対象とした不適切なプロテアーゼの働きを防止している可能性が指摘されている[188]。

ウイルスのセルピン

[編集]ウイルスもまた、宿主の免疫系による防御を回避するためにセルピンを発現する[191]。特に、牛痘ウイルス(ワクシニアウイルス)や兎粘液腫ウイルス(ミクソーマウイルス)を含むポックスウイルスが発現するセルピンは、自己免疫疾患や炎症性疾患、さらに移植療法における新規治療戦略となる可能性があるために興味深いものとなっている[192][193]。Serp1はTLR依存的自然免疫反応を抑制し、ラットの実験において同種心臓移植後の無期限の生存期間を可能にする[192][193][194]。CrmaとSerp2はクラス横断型阻害剤で、いずれもセリンプロテアーゼ(グランザイムB;効果は微弱)とシステインプロテアーゼ(カスパーゼ1とカスパーゼ8)の両者を標的とする[195][196]。哺乳類の相同分子と比較するとウイルスのセルピンは二次構造を明らかに欠損している。特にcrmAはAヘリックスおよびEヘリックスの大半とDヘリックスを欠いている[197]。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c d e Silverman GA, Bird PI, Carrell RW, Church FC, Coughlin PB, Gettins PG, Irving JA, Lomas DA, Luke CJ, Moyer RW, Pemberton PA, Remold-O'Donnell E, Salvesen GS, Travis J, Whisstock JC (September 2001). “The serpins are an expanding superfamily of structurally similar but functionally diverse proteins. Evolution, mechanism of inhibition, novel functions, and a revised nomenclature”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (36): 33293–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.R100016200. PMID 11435447.

- ^ Silverman GA, Whisstock JC, Bottomley SP, Huntington JA, Kaiserman D, Luke CJ, Pak SC, Reichhart JM, Bird PI (August 2010). “Serpins flex their muscle: I. Putting the clamps on proteolysis in diverse biological systems”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 285 (32): 24299–305. doi:10.1074/jbc.R110.112771. PMC 2915665. PMID 20498369.

- ^ Whisstock JC, Silverman GA, Bird PI, Bottomley SP, Kaiserman D, Luke CJ, Pak SC, Reichhart JM, Huntington JA (August 2010). “Serpins flex their muscle: II. Structural insights into target peptidase recognition, polymerization, and transport functions”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 285 (32): 24307–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.R110.141408. PMC 2915666. PMID 20498368.

- ^ a b c d e f Gettins PG (December 2002). “Serpin structure, mechanism, and function”. Chemical Reviews 102 (12): 4751–804. doi:10.1021/cr010170. PMID 12475206.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Whisstock JC, Bottomley SP (December 2006). “Molecular gymnastics: serpin structure, folding and misfolding”. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 16 (6): 761–8. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2006.10.005. PMID 17079131.

- ^ a b c d e f Law RH, Zhang Q, McGowan S, Buckle AM, Silverman GA, Wong W, Rosado CJ, Langendorf CG, Pike RN, Bird PI, Whisstock JC (2006). “An overview of the serpin superfamily”. Genome Biology 7 (5): 216. doi:10.1186/gb-2006-7-5-216. PMC 1779521. PMID 16737556.

- ^ a b c d e Stein PE, Carrell RW (February 1995). “What do dysfunctional serpins tell us about molecular mobility and disease?”. Nature Structural Biology 2 (2): 96–113. doi:10.1038/nsb0295-96. PMID 7749926.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Janciauskiene SM, Bals R, Koczulla R, Vogelmeier C, Köhnlein T, Welte T (August 2011). “The discovery of α1-antitrypsin and its role in health and disease”. Respiratory Medicine 105 (8): 1129–39. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2011.02.002. PMID 21367592.

- ^ a b c d Carrell RW, Lomas DA (July 1997). “Conformational disease”. Lancet 350 (9071): 134–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02073-4. PMID 9228977.

- ^ Fermi, C; Personsi, L (1984). “Untersuchungen uber die enzyme, Vergleichende Studie [Studies on the enzyme, Comparative study]” (German). Z Hyg Infektionskr (18): 83–89.

- ^ Schultz, H; Guilder, I; Heide, K; Schoenenberger, M; Schwick, G (1955). “Zur Kenntnis der alpha-globulin des menschlichen normal serums [For knowledge of the alpha - globulin of human normal serums]” (German). Naturforsch (10): 463.

- ^ Laurell CB, Eriksson S (2013). “The electrophoretic α1-globulin pattern of serum in α1-antitrypsin deficiency. 1963”. Copd 10 Suppl 1: 3–8. doi:10.3109/15412555.2013.771956. PMID 23527532.

- ^ a b de Serres, Frederick J. (1 November 2002). “Worldwide Racial and Ethnic Distribution of α-Antitrypsin Deficiency”. CHEST Journal 122 (5): 1818–1829. doi:10.1378/chest.122.5.1818.

- ^ Egeberg O (June 1965). “Inherited antithrombin deficiency causing thrombophilia”. Thrombosis Et Diathesis Haemorrhagica 13: 516–30. PMID 14347873.

- ^ a b Patnaik MM, Moll S (November 2008). “Inherited antithrombin deficiency: a review”. Haemophilia 14 (6): 1229–39. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01830.x. PMID 19141163.

- ^ a b Hunt LT, Dayhoff MO (July 1980). “A surprising new protein superfamily containing ovalbumin, antithrombin-III, and alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 95 (2): 864–71. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(80)90867-0. PMID 6968211.

- ^ a b Loebermann H, Tokuoka R, Deisenhofer J, Huber R (August 1984). “Human alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor. Crystal structure analysis of two crystal modifications, molecular model and preliminary analysis of the implications for function”. Journal of Molecular Biology 177 (3): 531–57. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(84)90298-5. PMID 6332197.

- ^ a b c Stein PE, Leslie AG, Finch JT, Turnell WG, McLaughlin PJ, Carrell RW (September 1990). “Crystal structure of ovalbumin as a model for the reactive centre of serpins”. Nature 347 (6288): 99–102. doi:10.1038/347099a0. PMID 2395463.

- ^ a b c Irving JA, Pike RN, Lesk AM, Whisstock JC (December 2000). “Phylogeny of the serpin superfamily: implications of patterns of amino acid conservation for structure and function”. Genome Research 10 (12): 1845–64. doi:10.1101/gr.GR-1478R. PMID 11116082.

- ^ a b Irving JA, Steenbakkers PJ, Lesk AM, Op den Camp HJ, Pike RN, Whisstock JC (November 2002). “Serpins in prokaryotes”. Molecular Biology and Evolution 19 (11): 1881–90. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004012. PMID 12411597.

- ^ a b Steenbakkers PJ, Irving JA, Harhangi HR, Swinkels WJ, Akhmanova A, Dijkerman R, Jetten MS, van der Drift C, Whisstock JC, Op den Camp HJ (August 2008). “A serpin in the cellulosome of the anaerobic fungus Piromyces sp. strain E2”. Mycological Research 112 (Pt 8): 999–1006. doi:10.1016/j.mycres.2008.01.021. PMID 18539447.

- ^ a b Rawlings ND, Tolle DP, Barrett AJ (March 2004). “Evolutionary families of peptidase inhibitors”. The Biochemical Journal 378 (Pt 3): 705–16. doi:10.1042/BJ20031825. PMC 1224039. PMID 14705960.

- ^ Barrett AJ, Rawlings ND (April 1995). “Families and clans of serine peptidases”. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 318 (2): 247–50. doi:10.1006/abbi.1995.1227. PMID 7733651.

- ^ a b Huntington JA, Read RJ, Carrell RW (October 2000). “Structure of a serpin-protease complex shows inhibition by deformation”. Nature 407 (6806): 923–6. doi:10.1038/35038119. PMID 11057674.

- ^ Barrett AJ, Rawlings ND (May 2001). “Evolutionary lines of cysteine peptidases”. Biological Chemistry 382 (5): 727–33. doi:10.1515/BC.2001.088. PMID 11517925.

- ^ Irving JA, Pike RN, Dai W, Brömme D, Worrall DM, Silverman GA, Coetzer TH, Dennison C, Bottomley SP, Whisstock JC (April 2002). “Evidence that serpin architecture intrinsically supports papain-like cysteine protease inhibition: engineering alpha(1)-antitrypsin to inhibit cathepsin proteases”. Biochemistry 41 (15): 4998–5004. doi:10.1021/bi0159985. PMID 11939796.

- ^ a b Schick C, Brömme D, Bartuski AJ, Uemura Y, Schechter NM, Silverman GA (November 1998). “The reactive site loop of the serpin SCCA1 is essential for cysteine proteinase inhibition”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95 (23): 13465–70. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13465. PMC 24842. PMID 9811823.

- ^ a b McGowan S, Buckle AM, Irving JA, Ong PC, Bashtannyk-Puhalovich TA, Kan WT, Henderson KN, Bulynko YA, Popova EY, Smith AI, Bottomley SP, Rossjohn J, Grigoryev SA, Pike RN, Whisstock JC (July 2006). “X-ray crystal structure of MENT: evidence for functional loop-sheet polymers in chromatin condensation”. The EMBO Journal 25 (13): 3144–55. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601201. PMC 1500978. PMID 16810322.

- ^ Ong PC, McGowan S, Pearce MC, Irving JA, Kan WT, Grigoryev SA, Turk B, Silverman GA, Brix K, Bottomley SP, Whisstock JC, Pike RN (December 2007). “DNA accelerates the inhibition of human cathepsin V by serpins”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (51): 36980–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.M706991200. PMID 17923478.

- ^ a b Acosta H, Iliev D, Grahn TH, Gouignard N, Maccarana M, Griesbach J, Herzmann S, Sagha M, Climent M, Pera EM (March 2015). “The serpin PN1 is a feedback regulator of FGF signaling in germ layer and primary axis formation”. Development 142 (6): 1146–58. doi:10.1242/dev.113886. PMID 25758225.

- ^ a b c Hashimoto C, Kim DR, Weiss LA, Miller JW, Morisato D (December 2003). “Spatial regulation of developmental signaling by a serpin”. Developmental Cell 5 (6): 945–50. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00338-1. PMID 14667416.

- ^ Bird PI (February 1999). “Regulation of pro-apoptotic leucocyte granule serine proteinases by intracellular serpins”. Immunology and Cell Biology 77 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1711.1999.00787.x. PMID 10101686.

- ^ Bird CH, Sutton VR, Sun J, Hirst CE, Novak A, Kumar S, Trapani JA, Bird PI (November 1998). “Selective regulation of apoptosis: the cytotoxic lymphocyte serpin proteinase inhibitor 9 protects against granzyme B-mediated apoptosis without perturbing the Fas cell death pathway”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 18 (11): 6387–98. doi:10.1128/mcb.18.11.6387. PMID 9774654.

- ^ Ray CA, Black RA, Kronheim SR, Greenstreet TA, Sleath PR, Salvesen GS, Pickup DJ (May 1992). “Viral inhibition of inflammation: cowpox virus encodes an inhibitor of the interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme”. Cell 69 (4): 597–604. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90223-Y. PMID 1339309.

- ^ a b Vercammen D, Belenghi B, van de Cotte B, Beunens T, Gavigan JA, De Rycke R, Brackenier A, Inzé D, Harris JL, Van Breusegem F (December 2006). “Serpin1 of Arabidopsis thaliana is a suicide inhibitor for metacaspase 9”. Journal of Molecular Biology 364 (4): 625–36. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.010. PMID 17028019.

- ^ a b Lampl N, Budai-Hadrian O, Davydov O, Joss TV, Harrop SJ, Curmi PM, Roberts TH, Fluhr R (April 2010). “Arabidopsis AtSerpin1, crystal structure and in vivo interaction with its target protease responsive to desiccation (RD21)”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 285 (18): 13550–60. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.095075. PMC 2859516. PMID 20181955.

- ^ a b c Klieber MA, Underhill C, Hammond GL, Muller YA (October 2007). “Corticosteroid-binding globulin, a structural basis for steroid transport and proteinase-triggered release”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (40): 29594–603. doi:10.1074/jbc.M705014200. PMID 17644521.

- ^ a b c d e Zhou A, Wei Z, Read RJ, Carrell RW (September 2006). “Structural mechanism for the carriage and release of thyroxine in the blood”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (36): 13321–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604080103. PMC 1557382. PMID 16938877.

- ^ Huntington JA, Stein PE (May 2001). “Structure and properties of ovalbumin”. Journal of Chromatography. B, Biomedical Sciences and Applications 756 (1-2): 189–98. doi:10.1016/S0378-4347(01)00108-6. PMID 11419711.

- ^ a b c Mala JG, Rose C (November 2010). “Interactions of heat shock protein 47 with collagen and the stress response: an unconventional chaperone model?”. Life Sciences 87 (19-22): 579–86. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2010.09.024. PMID 20888348.

- ^ Grigoryev SA, Bednar J, Woodcock CL (February 1999). “MENT, a heterochromatin protein that mediates higher order chromatin folding, is a new serpin family member”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 274 (9): 5626–36. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.9.5626. PMID 10026180.

- ^ Elliott PR, Lomas DA, Carrell RW, Abrahams JP (August 1996). “Inhibitory conformation of the reactive loop of alpha 1-antitrypsin”. Nature Structural Biology 3 (8): 676–81. doi:10.1038/nsb0896-676. PMID 8756325.

- ^ Horvath AJ, Irving JA, Rossjohn J, Law RH, Bottomley SP, Quinsey NS, Pike RN, Coughlin PB, Whisstock JC (December 2005). “The murine orthologue of human antichymotrypsin: a structural paradigm for clade A3 serpins”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 (52): 43168–78. doi:10.1074/jbc.M505598200. PMID 16141197.

- ^ Whisstock JC, Skinner R, Carrell RW, Lesk AM (February 2000). “Conformational changes in serpins: I. The native and cleaved conformations of alpha(1)-antitrypsin”. Journal of Molecular Biology 296 (2): 685–99. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3520. PMID 10669617.

- ^ a b 小出 武比古「セリンプロテアーゼとそのインヒビター--活性化,触媒機構ならびにその制御機構 (第1土曜特集 プロテアーゼとそのインヒビター--最新の知見) -- (おもなプロテアーゼとそのインヒビター--活性化ならびにその制御機構)」『医学のあゆみ』第198巻第1号、2001年、11-16頁、NAID 40000121445。

- ^ a b Huntington JA (August 2006). “Shape-shifting serpins--advantages of a mobile mechanism”. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 31 (8): 427–35. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2006.06.005. PMID 16820297.

- ^ Jin L, Abrahams JP, Skinner R, Petitou M, Pike RN, Carrell RW (December 1997). “The anticoagulant activation of antithrombin by heparin”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94 (26): 14683–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.26.14683. PMC 25092. PMID 9405673.

- ^ Whisstock JC, Pike RN, Jin L, Skinner R, Pei XY, Carrell RW, Lesk AM (September 2000). “Conformational changes in serpins: II. The mechanism of activation of antithrombin by heparin”. Journal of Molecular Biology 301 (5): 1287–305. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3982. PMID 10966821.

- ^ Li W, Johnson DJ, Esmon CT, Huntington JA (September 2004). “Structure of the antithrombin-thrombin-heparin ternary complex reveals the antithrombotic mechanism of heparin”. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 11 (9): 857–62. doi:10.1038/nsmb811. PMID 15311269.

- ^ Johnson DJ, Li W, Adams TE, Huntington JA (May 2006). “Antithrombin-S195A factor Xa-heparin structure reveals the allosteric mechanism of antithrombin activation”. The EMBO Journal 25 (9): 2029–37. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601089. PMC 1456925. PMID 16619025.

- ^ 城谷 裕子、小出 武比古「アンチトロンビンのプロテアーゼ阻害機構とヘパリンの作用機構 立体構造で見る動的構造変化」『日本血栓止血学会誌』第10巻第1号、1999年、93-99頁、doi:10.2491/jjsth.10.93、NAID 130004092829。

- ^ Walenga JM, Jeske WP, Samama MM, Frapaise FX, Bick RL, Fareed J (March 2002). “Fondaparinux: a synthetic heparin pentasaccharide as a new antithrombotic agent”. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 11 (3): 397–407. doi:10.1517/13543784.11.3.397. PMID 11866668.

- ^ Petitou M, van Boeckel CA (June 2004). “A synthetic antithrombin III binding pentasaccharide is now a drug! What comes next?”. Angewandte Chemie 43 (24): 3118–33. doi:10.1002/anie.200300640. PMID 15199558.

- ^ a b Lindahl TL, Sigurdardottir O, Wiman B (September 1989). “Stability of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1)”. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 62 (2): 748–51. PMID 2479113.

- ^ Mushunje A, Evans G, Brennan SO, Carrell RW, Zhou A (December 2004). “Latent antithrombin and its detection, formation and turnover in the circulation”. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2 (12): 2170–7. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01047.x. PMID 15613023.

- ^ Zhang Q, Buckle AM, Law RH, Pearce MC, Cabrita LD, Lloyd GJ, Irving JA, Smith AI, Ruzyla K, Rossjohn J, Bottomley SP, Whisstock JC (July 2007). “The N terminus of the serpin, tengpin, functions to trap the metastable native state”. EMBO Reports 8 (7): 658–63. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400986. PMC 1905895. PMID 17557112.

- ^ Zhang Q, Law RH, Bottomley SP, Whisstock JC, Buckle AM (March 2008). “A structural basis for loop C-sheet polymerization in serpins”. Journal of Molecular Biology 376 (5): 1348–59. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.050. PMID 18234218.

- ^ Pemberton PA, Stein PE, Pepys MB, Potter JM, Carrell RW (November 1988). “Hormone binding globulins undergo serpin conformational change in inflammation”. Nature 336 (6196): 257–8. doi:10.1038/336257a0. PMID 3143075.

- ^ a b c Cao C, Lawrence DA, Li Y, Von Arnim CA, Herz J, Su EJ, Makarova A, Hyman BT, Strickland DK, Zhang L (May 2006). “Endocytic receptor LRP together with tPA and PAI-1 coordinates Mac-1-dependent macrophage migration”. The EMBO Journal 25 (9): 1860–70. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601082. PMC 1456942. PMID 16601674.

- ^ Jensen JK, Dolmer K, Gettins PG (July 2009). “Specificity of binding of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein to different conformational states of the clade E serpins plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and proteinase nexin-1”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 284 (27): 17989–97. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.009530. PMC 2709341. PMID 19439404.

- ^ Soukup SF, Culi J, Gubb D (June 2009). Rulifson, Eric. ed. “Uptake of the necrotic serpin in Drosophila melanogaster via the lipophorin receptor-1”. PLoS Genetics 5 (6): e1000532. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000532. PMC 2694266. PMID 19557185.

- ^ Kaiserman D, Whisstock JC, Bird PI (1 January 2006). “Mechanisms of serpin dysfunction in disease”. Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine 8 (31): 1–19. doi:10.1017/S1462399406000184. PMID 17156576.

- ^ Hopkins PC, Carrell RW, Stone SR (August 1993). “Effects of mutations in the hinge region of serpins”. Biochemistry 32 (30): 7650–7. doi:10.1021/bi00081a008. PMID 8347575.

- ^ Beauchamp NJ, Pike RN, Daly M, Butler L, Makris M, Dafforn TR, Zhou A, Fitton HL, Preston FE, Peake IR, Carrell RW (October 1998). “Antithrombins Wibble and Wobble (T85M/K): archetypal conformational diseases with in vivo latent-transition, thrombosis, and heparin activation”. Blood 92 (8): 2696–706. PMID 9763552.

- ^ a b c Gooptu B, Hazes B, Chang WS, Dafforn TR, Carrell RW, Read RJ, Lomas DA (January 2000). “Inactive conformation of the serpin alpha(1)-antichymotrypsin indicates two-stage insertion of the reactive loop: implications for inhibitory function and conformational disease”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.1.67. PMC 26617. PMID 10618372.

- ^ a b Homan EP, Rauch F, Grafe I, Lietman C, Doll JA, Dawson B, Bertin T, Napierala D, Morello R, Gibbs R, White L, Miki R, Cohn DH, Crawford S, Travers R, Glorieux FH, Lee B (December 2011). “Mutations in SERPINF1 cause osteogenesis imperfecta type VI”. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 26 (12): 2798–803. doi:10.1002/jbmr.487. PMC 3214246. PMID 21826736.

- ^ Fay WP, Parker AC, Condrey LR, Shapiro AD (July 1997). “Human plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) deficiency: characterization of a large kindred with a null mutation in the PAI-1 gene”. Blood 90 (1): 204–8. PMID 9207454.

- ^ a b c d e f Heit C, Jackson BC, McAndrews M, Wright MW, Thompson DC, Silverman GA, Nebert DW, Vasiliou V (30 October 2013). “Update of the human and mouse SERPIN gene superfamily”. Human Genomics 7: 22. doi:10.1186/1479-7364-7-22. PMC 3880077. PMID 24172014.

- ^ Owen MC, Brennan SO, Lewis JH, Carrell RW (September 1983). “Mutation of antitrypsin to antithrombin. alpha 1-antitrypsin Pittsburgh (358 Met leads to Arg), a fatal bleeding disorder”. The New England Journal of Medicine 309 (12): 694–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM198309223091203. PMID 6604220.

- ^ a b Lomas DA, Evans DL, Finch JT, Carrell RW (June 1992). “The mechanism of Z alpha 1-antitrypsin accumulation in the liver”. Nature 357 (6379): 605–7. doi:10.1038/357605a0. PMID 1608473.

- ^ 恩田 真紀「セルピノパシー : セルピンのポリマー化により発症するコンフォメーション病 : ニューロセルピン封入体形成による若年性痴呆症」『化学と生物』第43巻第8号、2005年、488-490頁、NAID 10019044214。

- ^ Kroeger H, Miranda E, MacLeod I, Pérez J, Crowther DC, Marciniak SJ, Lomas DA (August 2009). “Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) and autophagy cooperate to degrade polymerogenic mutant serpins”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 284 (34): 22793–802. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.027102. PMC 2755687. PMID 19549782.

- ^ a b c Yamasaki M, Li W, Johnson DJ, Huntington JA (October 2008). “Crystal structure of a stable dimer reveals the molecular basis of serpin polymerization”. Nature 455 (7217): 1255–8. doi:10.1038/nature07394. PMID 18923394.

- ^ a b Bottomley SP (October 2011). “The structural diversity in α1-antitrypsin misfolding”. EMBO Reports 12 (10): 983–4. doi:10.1038/embor.2011.187. PMC 3185355. PMID 21921939.

- ^ a b Yamasaki M, Sendall TJ, Pearce MC, Whisstock JC, Huntington JA (October 2011). “Molecular basis of α1-antitrypsin deficiency revealed by the structure of a domain-swapped trimer”. EMBO Reports 12 (10): 1011–7. doi:10.1038/embor.2011.171. PMC 3185345. PMID 21909074.

- ^ Chang WS, Whisstock J, Hopkins PC, Lesk AM, Carrell RW, Wardell MR (January 1997). “Importance of the release of strand 1C to the polymerization mechanism of inhibitory serpins”. Protein Science 6 (1): 89–98. doi:10.1002/pro.5560060110. PMC 2143506. PMID 9007980.

- ^ Miranda E, Pérez J, Ekeowa UI, Hadzic N, Kalsheker N, Gooptu B, Portmann B, Belorgey D, Hill M, Chambers S, Teckman J, Alexander GJ, Marciniak SJ, Lomas DA (September 2010). “A novel monoclonal antibody to characterize pathogenic polymers in liver disease associated with alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency”. Hepatology 52 (3): 1078–88. doi:10.1002/hep.23760. PMID 20583215.

- ^ Sandhaus RA (October 2004). “alpha1-Antitrypsin deficiency . 6: new and emerging treatments for alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency”. Thorax 59 (10): 904–9. doi:10.1136/thx.2003.006551. PMC 1746849. PMID 15454659.

- ^ Lewis EC. “Expanding the clinical indications for α(1)-antitrypsin therapy”. Molecular Medicine 18 (6): 957–70. doi:10.2119/molmed.2011.00196. PMC 3459478. PMID 22634722.

- ^ Fregonese L, Stolk J (2008). “Hereditary alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency and its clinical consequences”. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 3: 16. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-3-16. PMC 2441617. PMID 18565211.

- ^ Yusa K, Rashid ST, Strick-Marchand H, Varela I, Liu PQ, Paschon DE, Miranda E, Ordóñez A, Hannan NR, Rouhani FJ, Darche S, Alexander G, Marciniak SJ, Fusaki N, Hasegawa M, Holmes MC, Di Santo JP, Lomas DA, Bradley A, Vallier L (October 2011). “Targeted gene correction of α1-antitrypsin deficiency in induced pluripotent stem cells”. Nature 478 (7369): 391–4. doi:10.1038/nature10424. PMC 3198846. PMID 21993621.

- ^ Mallya M, Phillips RL, Saldanha SA, Gooptu B, Brown SC, Termine DJ, Shirvani AM, Wu Y, Sifers RN, Abagyan R, Lomas DA (November 2007). “Small molecules block the polymerization of Z alpha1-antitrypsin and increase the clearance of intracellular aggregates”. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 50 (22): 5357–63. doi:10.1021/jm070687z. PMC 2631427. PMID 17918823.

- ^ Gosai SJ, Kwak JH, Luke CJ, Long OS, King DE, Kovatch KJ, Johnston PA, Shun TY, Lazo JS, Perlmutter DH, Silverman GA, Pak SC (2010). “Automated high-content live animal drug screening using C. elegans expressing the aggregation prone serpin α1-antitrypsin Z”. PloS One 5 (11): e15460. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015460. PMC 2980495. PMID 21103396.

- ^ Cabrita LD, Irving JA, Pearce MC, Whisstock JC, Bottomley SP (September 2007). “Aeropin from the extremophile Pyrobaculum aerophilum bypasses the serpin misfolding trap”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (37): 26802–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M705020200. PMID 17635906.

- ^ Fluhr R, Lampl N, Roberts TH (May 2012). “Serpin protease inhibitors in plant biology”. Physiologia Plantarum 145 (1): 95–102. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.2011.01540.x. PMID 22085334.

- ^ Stoller JK, Aboussouan LS (2005). “Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency”. Lancet 365 (9478): 2225–36. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66781-5. PMID 15978931.

- ^ Münch J, Ständker L, Adermann K, Schulz A, Schindler M, Chinnadurai R, Pöhlmann S, Chaipan C, Biet T, Peters T, Meyer B, Wilhelm D, Lu H, Jing W, Jiang S, Forssmann WG, Kirchhoff F (April 2007). “Discovery and optimization of a natural HIV-1 entry inhibitor targeting the gp41 fusion peptide”. Cell 129 (2): 263–75. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.042. PMID 17448989.

- ^ Gooptu B, Dickens JA, Lomas DA (February 2014). “The molecular and cellular pathology of α₁-antitrypsin deficiency”. Trends in Molecular Medicine 20 (2): 116–27. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2013.10.007. PMID 24374162.

- ^ Seixas S, Suriano G, Carvalho F, Seruca R, Rocha J, Di Rienzo A (February 2007). “Sequence diversity at the proximal 14q32.1 SERPIN subcluster: evidence for natural selection favoring the pseudogenization of SERPINA2”. Molecular Biology and Evolution 24 (2): 587–98. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl187. PMID 17135331.

- ^ Kalsheker NA (September 1996). “Alpha 1-antichymotrypsin”. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 28 (9): 961–4. doi:10.1016/1357-2725(96)00032-5. PMID 8930118.

- ^ Santamaria M, Pardo-Saganta A, Alvarez-Asiain L, Di Scala M, Qian C, Prieto J, Avila MA (April 2013). “Nuclear α1-antichymotrypsin promotes chromatin condensation and inhibits proliferation of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells”. Gastroenterology 144 (4): 818–828.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.029. PMID 23295442.

- ^ Zhang S, Janciauskiene S (April 2002). “Multi-functional capability of proteins: alpha1-antichymotrypsin and the correlation with Alzheimer's disease”. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 4 (2): 115–22. PMID 12214135.

- ^ Chao J, Stallone JN, Liang YM, Chen LM, Wang DZ, Chao L (July 1997). “Kallistatin is a potent new vasodilator”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 100 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1172/JCI119502. PMC 508159. PMID 9202051.

- ^ Miao RQ, Agata J, Chao L, Chao J (November 2002). “Kallistatin is a new inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth”. Blood 100 (9): 3245–52. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-01-0185. PMID 12384424.

- ^ Liu Y, Bledsoe G, Hagiwara M, Shen B, Chao L, Chao J (October 2012). “Depletion of endogenous kallistatin exacerbates renal and cardiovascular oxidative stress, inflammation, and organ remodeling”. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology 303 (8): F1230-8. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00257.2012. PMID 22811485.

- ^ Geiger M (March 2007). “Protein C inhibitor, a serpin with functions in- and outside vascular biology”. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 97 (3): 343–7. doi:10.1160/th06-09-0488. PMID 17334499.

- ^ Baumgärtner P, Geiger M, Zieseniss S, Malleier J, Huntington JA, Hochrainer K, Bielek E, Stoeckelhuber M, Lauber K, Scherfeld D, Schwille P, Wäldele K, Beyer K, Engelmann B (November 2007). “Phosphatidylethanolamine critically supports internalization of cell-penetrating protein C inhibitor”. The Journal of Cell Biology 179 (4): 793–804. doi:10.1083/jcb.200707165. PMC 2080921. PMID 18025309.

- ^ Uhrin P, Dewerchin M, Hilpert M, Chrenek P, Schöfer C, Zechmeister-Machhart M, Krönke G, Vales A, Carmeliet P, Binder BR, Geiger M (December 2000). “Disruption of the protein C inhibitor gene results in impaired spermatogenesis and male infertility”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 106 (12): 1531–9. doi:10.1172/JCI10768. PMC 381472. PMID 11120760.

- ^ Han MH, Hwang SI, Roy DB, Lundgren DH, Price JV, Ousman SS, Fernald GH, Gerlitz B, Robinson WH, Baranzini SE, Grinnell BW, Raine CS, Sobel RA, Han DK, Steinman L (February 2008). “Proteomic analysis of active multiple sclerosis lesions reveals therapeutic targets”. Nature 451 (7182): 1076–81. doi:10.1038/nature06559. PMID 18278032.

- ^ Torpy DJ, Ho JT (August 2007). “Corticosteroid-binding globulin gene polymorphisms: clinical implications and links to idiopathic chronic fatigue disorders”. Clinical Endocrinology 67 (2): 161–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02890.x. PMID 17547679.

- ^ Bartalena L, Robbins J (1992). “Variations in thyroid hormone transport proteins and their clinical implications”. Thyroid 2 (3): 237–45. doi:10.1089/thy.1992.2.237. PMID 1422238.

- ^ Persani L (September 2012). “Clinical review: Central hypothyroidism: pathogenic, diagnostic, and therapeutic challenges”. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 97 (9): 3068–78. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-1616. PMID 22851492.

- ^ Kumar R, Singh VP, Baker KM (July 2007). “The intracellular renin-angiotensin system: a new paradigm”. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 18 (5): 208–14. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2007.05.001. PMID 17509892.

- ^ Tanimoto K, Sugiyama F, Goto Y, Ishida J, Takimoto E, Yagami K, Fukamizu A, Murakami K (December 1994). “Angiotensinogen-deficient mice with hypotension”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 269 (50): 31334–7. PMID 7989296.

- ^ Jeunemaitre X, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Célérier J, Corvol P (1999). “Angiotensinogen variants and human hypertension”. Current Hypertension Reports 1 (1): 31–41. doi:10.1007/s11906-999-0071-0. PMID 10981040.

- ^ Sethi AA, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A (July 2003). “Angiotensinogen gene polymorphism, plasma angiotensinogen, and risk of hypertension and ischemic heart disease: a meta-analysis”. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 23 (7): 1269–75. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000079007.40884.5C. PMID 12805070.

- ^ Dickson ME, Sigmund CD (July 2006). “Genetic basis of hypertension: revisiting angiotensinogen”. Hypertension 48 (1): 14–20. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000227932.13687.60. PMID 16754793.

- ^ Frazer JK, Jackson DG, Gaillard JP, Lutter M, Liu YJ, Banchereau J, Capra JD, Pascual V (October 2000). “Identification of centerin: a novel human germinal center B cell-restricted serpin”. European Journal of Immunology 30 (10): 3039–48. doi:10.1002/1521-4141(200010)30:10<3039::AID-IMMU3039>3.0.CO;2-H. PMID 11069088.

- ^ Paterson MA, Horvath AJ, Pike RN, Coughlin PB (August 2007). “Molecular characterization of centerin, a germinal centre cell serpin”. The Biochemical Journal 405 (3): 489–94. doi:10.1042/BJ20070174. PMC 2267310. PMID 17447896.

- ^ Paterson MA, Hosking PS, Coughlin PB (July 2008). “Expression of the serpin centerin defines a germinal center phenotype in B-cell lymphomas”. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 130 (1): 117–26. doi:10.1309/9QKE68QU7B825A3U. PMID 18550480.

- ^ Ashton-Rickardt PG (April 2013). “An emerging role for Serine Protease Inhibitors in T lymphocyte immunity and beyond”. Immunology Letters 152 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2013.04.004. PMID 23624075.

- ^ Han X, Fiehler R, Broze GJ (November 2000). “Characterization of the protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor”. Blood 96 (9): 3049–55. PMID 11049983.

- ^ Hida K, Wada J, Eguchi J, Zhang H, Baba M, Seida A, Hashimoto I, Okada T, Yasuhara A, Nakatsuka A, Shikata K, Hourai S, Futami J, Watanabe E, Matsuki Y, Hiramatsu R, Akagi S, Makino H, Kanwar YS (July 2005). “Visceral adipose tissue-derived serine protease inhibitor: a unique insulin-sensitizing adipocytokine in obesity”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (30): 10610–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504703102. PMC 1180799. PMID 16030142.

- ^ Feng R, Li Y, Wang C, Luo C, Liu L, Chuo F, Li Q, Sun C (October 2014). “Higher vaspin levels in subjects with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis”. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 106 (1): 88–94. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2014.07.026. PMID 25151227.

- ^ Remold-O'Donnell E, Chin J, Alberts M (June 1992). “Sequence and molecular characterization of human monocyte/neutrophil elastase inhibitor”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 89 (12): 5635–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.12.5635. PMC 49347. PMID 1376927.

- ^ Benarafa C, Priebe GP, Remold-O'Donnell E (August 2007). “The neutrophil serine protease inhibitor serpinb1 preserves lung defense functions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 204 (8): 1901–9. doi:10.1084/jem.20070494. PMC 2118684. PMID 17664292.

- ^ Antalis TM, La Linn M, Donnan K, Mateo L, Gardner J, Dickinson JL, Buttigieg K, Suhrbier A (June 1998). “The serine proteinase inhibitor (serpin) plasminogen activation inhibitor type 2 protects against viral cytopathic effects by constitutive interferon alpha/beta priming”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 187 (11): 1799–811. doi:10.1084/jem.187.11.1799. PMC 2212304. PMID 9607921.

- ^ Zhao A, Yang Z, Sun R, Grinchuk V, Netzel-Arnett S, Anglin IE, Driesbaugh KH, Notari L, Bohl JA, Madden KB, Urban JF, Antalis TM, Shea-Donohue T (June 2013). “SerpinB2 is critical to Th2 immunity against enteric nematode infection”. Journal of Immunology 190 (11): 5779–87. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1200293. PMID 23630350.

- ^ Dougherty KM, Pearson JM, Yang AY, Westrick RJ, Baker MS, Ginsburg D (January 1999). “The plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 gene is not required for normal murine development or survival”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96 (2): 686–91. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.2.686. PMC 15197. PMID 9892694.

- ^ Takeda A, Yamamoto T, Nakamura Y, Takahashi T, Hibino T (February 1995). “Squamous cell carcinoma antigen is a potent inhibitor of cysteine proteinase cathepsin L”. FEBS Letters 359 (1): 78–80. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)01456-b. PMID 7851535.

- ^ a b Turato C, Pontisso P (March 2015). “SERPINB3 (serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin), member 3)”. Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology 19 (3): 202–209. doi:10.4267/2042/56413. PMC 4430857. PMID 25984243.

- ^ a b Sivaprasad U, Askew DJ, Ericksen MB, Gibson AM, Stier MT, Brandt EB, Bass SA, Daines MO, Chakir J, Stringer KF, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Le Cras TD, Wills-Karp M, Silverman GA, Khurana Hershey GK (January 2011). “A nonredundant role for mouse Serpinb3a in the induction of mucus production in asthma”. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 127 (1): 254–61, 261.e1-6. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.009. PMC 3058372. PMID 21126757.

- ^ Schick C, Kamachi Y, Bartuski AJ, Cataltepe S, Schechter NM, Pemberton PA, Silverman GA (January 1997). “Squamous cell carcinoma antigen 2 is a novel serpin that inhibits the chymotrypsin-like proteinases cathepsin G and mast cell chymase”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 272 (3): 1849–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.3.1849. PMID 8999871.

- ^ Teoh SS, Whisstock JC, Bird PI (April 2010). “Maspin (SERPINB5) is an obligate intracellular serpin”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 285 (14): 10862–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.073171. PMC 2856292. PMID 20123984.

- ^ Zou Z, Anisowicz A, Hendrix MJ, Thor A, Neveu M, Sheng S, Rafidi K, Seftor E, Sager R (January 1994). “Maspin, a serpin with tumor-suppressing activity in human mammary epithelial cells”. Science 263 (5146): 526–9. doi:10.1126/science.8290962. PMID 8290962.

- ^ a b c Teoh SS, Vieusseux J, Prakash M, Berkowicz S, Luu J, Bird CH, Law RH, Rosado C, Price JT, Whisstock JC, Bird PI (2014). “Maspin is not required for embryonic development or tumour suppression”. Nature Communications 5: 3164. doi:10.1038/ncomms4164. PMC 3905777. PMID 24445777.

- ^ Gao F, Shi HY, Daughty C, Cella N, Zhang M (April 2004). “Maspin plays an essential role in early embryonic development”. Development 131 (7): 1479–89. doi:10.1242/dev.01048. PMID 14985257.

- ^ Scott FL, Hirst CE, Sun J, Bird CH, Bottomley SP, Bird PI (March 1999). “The intracellular serpin proteinase inhibitor 6 is expressed in monocytes and granulocytes and is a potent inhibitor of the azurophilic granule protease, cathepsin G”. Blood 93 (6): 2089–97. PMID 10068683.

- ^ Tan J, Prakash MD, Kaiserman D, Bird PI (July 2013). “Absence of SERPINB6A causes sensorineural hearing loss with multiple histopathologies in the mouse inner ear”. The American Journal of Pathology 183 (1): 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.03.009. PMID 23669344.

- ^ Scarff KL, Ung KS, Nandurkar H, Crack PJ, Bird CH, Bird PI (May 2004). “Targeted disruption of SPI3/Serpinb6 does not result in developmental or growth defects, leukocyte dysfunction, or susceptibility to stroke”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 24 (9): 4075–82. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.9.4075-4082.2004. PMC 387772. PMID 15082799.

- ^ Naz, Sadaf (2012). Genetics of Nonsyndromic Recessively Inherited Moderate to Severe and Progressive Deafness in Humans. InTech. pp. 260. doi:10.5772/31808. ISBN 978-953-51-0366-0

- ^ Miyata T, Inagi R, Nangaku M, Imasawa T, Sato M, Izuhara Y, Suzuki D, Yoshino A, Onogi H, Kimura M, Sugiyama S, Kurokawa K (March 2002). “Overexpression of the serpin megsin induces progressive mesangial cell proliferation and expansion”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 109 (5): 585–93. doi:10.1172/JCI14336. PMC 150894. PMID 11877466.

- ^ a b Miyata T, Li M, Yu X, Hirayama N (May 2007). “Megsin gene: its genomic analysis, pathobiological functions, and therapeutic perspectives”. Current Genomics 8 (3): 203–8. doi:10.2174/138920207780833856. PMC 2435355. PMID 18645605.

- ^ Kubo A (August 2014). “Nagashima-type palmoplantar keratosis: a common Asian type caused by SERPINB7 protease inhibitor deficiency”. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 134 (8): 2076–9. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.156. PMID 25029323.

- ^ Dahlen JR, Jean F, Thomas G, Foster DC, Kisiel W (January 1998). “Inhibition of soluble recombinant furin by human proteinase inhibitor 8”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (4): 1851–4. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.4.1851. PMID 9442015.

- ^ Sun J, Bird CH, Sutton V, McDonald L, Coughlin PB, De Jong TA, Trapani JA, Bird PI (November 1996). “A cytosolic granzyme B inhibitor related to the viral apoptotic regulator cytokine response modifier A is present in cytotoxic lymphocytes”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 271 (44): 27802–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.44.27802. PMID 8910377.

- ^ Zhang M, Park SM, Wang Y, Shah R, Liu N, Murmann AE, Wang CR, Peter ME, Ashton-Rickardt PG (April 2006). “Serine protease inhibitor 6 protects cytotoxic T cells from self-inflicted injury by ensuring the integrity of cytotoxic granules”. Immunity 24 (4): 451–61. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.002. PMID 16618603.

- ^ Rizzitelli A, Meuter S, Vega Ramos J, Bird CH, Mintern JD, Mangan MS, Villadangos J, Bird PI (October 2012). “Serpinb9 (Spi6)-deficient mice are impaired in dendritic cell-mediated antigen cross-presentation”. Immunology and Cell Biology 90 (9): 841–51. doi:10.1038/icb.2012.29. PMID 22801574.

- ^ Riewald M, Chuang T, Neubauer A, Riess H, Schleef RR (February 1998). “Expression of bomapin, a novel human serpin, in normal/malignant hematopoiesis and in the monocytic cell lines THP-1 and AML-193”. Blood 91 (4): 1256–62. PMID 9454755.

- ^ a b Askew DJ, Cataltepe S, Kumar V, Edwards C, Pace SM, Howarth RN, Pak SC, Askew YS, Brömme D, Luke CJ, Whisstock JC, Silverman GA (August 2007). “SERPINB11 is a new noninhibitory intracellular serpin. Common single nucleotide polymorphisms in the scaffold impair conformational change”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (34): 24948–60. doi:10.1074/jbc.M703182200. PMID 17562709.

- ^ Finno CJ, Stevens C, Young A, Affolter V, Joshi NA, Ramsay S, Bannasch DL (April 2015). “SERPINB11 frameshift variant associated with novel hoof specific phenotype in Connemara ponies”. PLoS Genetics 11 (4): e1005122. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005122. PMID 25875171.

- ^ Askew YS, Pak SC, Luke CJ, Askew DJ, Cataltepe S, Mills DR, Kato H, Lehoczky J, Dewar K, Birren B, Silverman GA (December 2001). “SERPINB12 is a novel member of the human ov-serpin family that is widely expressed and inhibits trypsin-like serine proteinases”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (52): 49320–30. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108879200. PMID 11604408.

- ^ Welss T, Sun J, Irving JA, Blum R, Smith AI, Whisstock JC, Pike RN, von Mikecz A, Ruzicka T, Bird PI, Abts HF (June 2003). “Hurpin is a selective inhibitor of lysosomal cathepsin L and protects keratinocytes from ultraviolet-induced apoptosis”. Biochemistry 42 (24): 7381–9. doi:10.1021/bi027307q. PMID 12809493.

- ^ Ishiguro K, Kojima T, Kadomatsu K, Nakayama Y, Takagi A, Suzuki M, Takeda N, Ito M, Yamamoto K, Matsushita T, Kusugami K, Muramatsu T, Saito H (October 2000). “Complete antithrombin deficiency in mice results in embryonic lethality”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 106 (7): 873–8. doi:10.1172/JCI10489. PMC 517819. PMID 11018075.

- ^ Huntington JA (July 2011). “Serpin structure, function and dysfunction”. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 9 Suppl 1: 26–34. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04360.x. PMID 21781239.

- ^ Vicente CP, He L, Pavão MS, Tollefsen DM (December 2004). “Antithrombotic activity of dermatan sulfate in heparin cofactor II-deficient mice”. Blood 104 (13): 3965–70. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-02-0598. PMID 15315969.

- ^ Aihara K, Azuma H, Akaike M, Ikeda Y, Sata M, Takamori N, Yagi S, Iwase T, Sumitomo Y, Kawano H, Yamada T, Fukuda T, Matsumoto T, Sekine K, Sato T, Nakamichi Y, Yamamoto Y, Yoshimura K, Watanabe T, Nakamura T, Oomizu A, Tsukada M, Hayashi H, Sudo T, Kato S, Matsumoto T (June 2007). “Strain-dependent embryonic lethality and exaggerated vascular remodeling in heparin cofactor II-deficient mice”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 117 (6): 1514–26. doi:10.1172/JCI27095. PMC 1878511. PMID 17549254.

- ^ Cale JM, Lawrence DA (September 2007). “Structure-function relationships of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and its potential as a therapeutic agent”. Current Drug Targets 8 (9): 971–81. doi:10.2174/138945007781662337. PMID 17896949.

- ^ Lino MM, Atanasoski S, Kvajo M, Fayard B, Moreno E, Brenner HR, Suter U, Monard D (April 2007). “Mice lacking protease nexin-1 show delayed structural and functional recovery after sciatic nerve crush”. The Journal of Neuroscience 27 (14): 3677–85. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0277-07.2007. PMID 17409231.

- ^ Murer V, Spetz JF, Hengst U, Altrogge LM, de Agostini A, Monard D (March 2001). “Male fertility defects in mice lacking the serine protease inhibitor protease nexin-1”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98 (6): 3029–33. doi:10.1073/pnas.051630698. PMC 30601. PMID 11248026.

- ^ Lüthi A, Van der Putten H, Botteri FM, Mansuy IM, Meins M, Frey U, Sansig G, Portet C, Schmutz M, Schröder M, Nitsch C, Laurent JP, Monard D (June 1997). “Endogenous serine protease inhibitor modulates epileptic activity and hippocampal long-term potentiation”. The Journal of Neuroscience 17 (12): 4688–99. PMID 9169529.

- ^ a b Doll JA, Stellmach VM, Bouck NP, Bergh AR, Lee C, Abramson LP, Cornwell ML, Pins MR, Borensztajn J, Crawford SE (June 2003). “Pigment epithelium-derived factor regulates the vasculature and mass of the prostate and pancreas”. Nature Medicine 9 (6): 774–80. doi:10.1038/nm870. PMID 12740569.

- ^ Becerra SP, Perez-Mediavilla LA, Weldon JE, Locatelli-Hoops S, Senanayake P, Notari L, Notario V, Hollyfield JG (November 2008). “Pigment epithelium-derived factor binds to hyaluronan. Mapping of a hyaluronan binding site”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 283 (48): 33310–20. doi:10.1074/jbc.M801287200. PMC 2586245. PMID 18805795.

- ^ Andreu-Agulló C, Morante-Redolat JM, Delgado AC, Fariñas I (December 2009). “Vascular niche factor PEDF modulates Notch-dependent stemness in the adult subependymal zone”. Nature Neuroscience 12 (12): 1514–23. doi:10.1038/nn.2437. PMID 19898467.

- ^ Wiman B, Collen D (September 1979). “On the mechanism of the reaction between human alpha 2-antiplasmin and plasmin”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 254 (18): 9291–7. PMID 158022.

- ^ Lijnen HR, Okada K, Matsuo O, Collen D, Dewerchin M (April 1999). “Alpha2-antiplasmin gene deficiency in mice is associated with enhanced fibrinolytic potential without overt bleeding”. Blood 93 (7): 2274–81. PMID 10090937.

- ^ Carpenter SL, Mathew P (November 2008). “Alpha2-antiplasmin and its deficiency: fibrinolysis out of balance”. Haemophilia 14 (6): 1250–4. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01766.x. PMID 19141165.

- ^ Favier, R.; Aoki, N.; De Moerloose, P. (1 July 2001). “Congenital α2-plasmin inhibitor deficiencies: a review”. British Journal of Haematology 114 (1): 4–10. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02845.x. ISSN 1365-2141.

- ^ Beinrohr L, Harmat V, Dobó J, Lörincz Z, Gál P, Závodszky P (July 2007). “C1 inhibitor serpin domain structure reveals the likely mechanism of heparin potentiation and conformational disease”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (29): 21100–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M700841200. PMID 17488724.

- ^ Mollnes TE, Jokiranta TS, Truedsson L, Nilsson B, Rodriguez de Cordoba S, Kirschfink M (September 2007). “Complement analysis in the 21st century”. Molecular Immunology 44 (16): 3838–49. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2007.06.150. PMID 17768101.

- ^ Triggianese P, Chimenti MS, Toubi E, Ballanti E, Guarino MD, Perricone C, Perricone R (August 2015). “The autoimmune side of hereditary angioedema: insights on the pathogenesis”. Autoimmunity Reviews 14 (8): 665–9. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2015.03.006. PMID 25827463.

- ^ Nagai N, Hosokawa M, Itohara S, Adachi E, Matsushita T, Hosokawa N, Nagata K (September 2000). “Embryonic lethality of molecular chaperone hsp47 knockout mice is associated with defects in collagen biosynthesis”. The Journal of Cell Biology 150 (6): 1499–506. doi:10.1083/jcb.150.6.1499. PMC 2150697. PMID 10995453.

- ^ Marini JC, Reich A, Smith SM (August 2014). “Osteogenesis imperfecta due to mutations in non-collagenous genes: lessons in the biology of bone formation”. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 26 (4): 500–7. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000117. PMC 4183132. PMID 25007323.

- ^ Byers PH, Pyott SM (1 January 2012). “Recessively inherited forms of osteogenesis imperfecta”. Annual Review of Genetics 46: 475–97. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155608. PMID 23145505.

- ^ Osterwalder T, Cinelli P, Baici A, Pennella A, Krueger SR, Schrimpf SP, Meins M, Sonderegger P (January 1998). “The axonally secreted serine proteinase inhibitor, neuroserpin, inhibits plasminogen activators and plasmin but not thrombin”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (4): 2312–21. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.4.2312. PMID 9442076.

- ^ Crowther DC (July 2002). “Familial conformational diseases and dementias”. Human Mutation 20 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1002/humu.10100. PMID 12112652.

- ^ Belorgey D, Hägglöf P, Karlsson-Li S, Lomas DA (1 March 2007). “Protein misfolding and the serpinopathies”. Prion 1 (1): 15–20. doi:10.4161/pri.1.1.3974. PMC 2633702. PMID 19164889.

- ^ Ozaki K, Nagata M, Suzuki M, Fujiwara T, Miyoshi Y, Ishikawa O, Ohigashi H, Imaoka S, Takahashi E, Nakamura Y (July 1998). “Isolation and characterization of a novel human pancreas-specific gene, pancpin, that is down-regulated in pancreatic cancer cells”. Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer 22 (3): 179–85. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199807)22:3<179::AID-GCC3>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 9624529.

- ^ Loftus SK, Cannons JL, Incao A, Pak E, Chen A, Zerfas PM, Bryant MA, Biesecker LG, Schwartzberg PL, Pavan WJ (September 2005). “Acinar cell apoptosis in Serpini2-deficient mice models pancreatic insufficiency”. PLoS Genetics 1 (3): e38. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0010038. PMC 1231717. PMID 16184191.

- ^ Padua MB, Kowalski AA, Cañas MY, Hansen PJ (February 2010). “The molecular phylogeny of uterine serpins and its relationship to evolution of placentation”. FASEB Journal 24 (2): 526–37. doi:10.1096/fj.09-138453. PMID 19825977.

- ^ Padua MB, Hansen PJ (October 2010). “Evolution and function of the uterine serpins (SERPINA14)”. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 64 (4): 265–74. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00901.x. PMID 20678169.

- ^ a b Reichhart JM (December 2005). “Tip of another iceberg: Drosophila serpins”. Trends in Cell Biology 15 (12): 659–65. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2005.10.001. PMID 16260136.

- ^ Tang H, Kambris Z, Lemaitre B, Hashimoto C (October 2008). “A serpin that regulates immune melanization in the respiratory system of Drosophila”. Developmental Cell 15 (4): 617–26. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.017. PMC 2671232. PMID 18854145.

- ^ Scherfer C, Tang H, Kambris Z, Lhocine N, Hashimoto C, Lemaitre B (November 2008). “Drosophila Serpin-28D regulates hemolymph phenoloxidase activity and adult pigmentation”. Developmental Biology 323 (2): 189–96. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.030. PMID 18801354.

- ^ Rushlow C (January 2004). “Dorsoventral patterning: a serpin pinned down at last”. Current Biology 14 (1): R16-8. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.015. PMID 14711428.

- ^ Ligoxygakis P, Roth S, Reichhart JM (December 2003). “A serpin regulates dorsal-ventral axis formation in the Drosophila embryo”. Current Biology 13 (23): 2097–102. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.062. PMID 14654000.

- ^ Jiang R, Zhang B, Kurokawa K, So YI, Kim EH, Hwang HO, Lee JH, Shiratsuchi A, Zhang J, Nakanishi Y, Lee HS, Lee BL (October 2011). “93-kDa twin-domain serine protease inhibitor (Serpin) has a regulatory function on the beetle Toll proteolytic signaling cascade”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 286 (40): 35087–95. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.277343. PMC 3186399. PMID 21862574.

- ^ a b Pak SC, Kumar V, Tsu C, Luke CJ, Askew YS, Askew DJ, Mills DR, Brömme D, Silverman GA (April 2004). “SRP-2 is a cross-class inhibitor that participates in postembryonic development of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: initial characterization of the clade L serpins”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 (15): 15448–59. doi:10.1074/jbc.M400261200. PMID 14739286.

- ^ Luke CJ, Pak SC, Askew YS, Naviglia TL, Askew DJ, Nobar SM, Vetica AC, Long OS, Watkins SC, Stolz DB, Barstead RJ, Moulder GL, Brömme D, Silverman GA (September 2007). “An intracellular serpin regulates necrosis by inhibiting the induction and sequelae of lysosomal injury”. Cell 130 (6): 1108–19. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.013. PMC 2128786. PMID 17889653.

- ^ Dahl SW, Rasmussen SK, Petersen LC, Hejgaard J (September 1996). “Inhibition of coagulation factors by recombinant barley serpin BSZx”. FEBS Letters 394 (2): 165–8. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00940-4. PMID 8843156.

- ^ Hejgaard J (January 2001). “Inhibitory serpins from rye grain with glutamine as P1 and P2 residues in the reactive center”. FEBS Letters 488 (3): 149–53. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(00)02425-X. PMID 11163762.

- ^ Ostergaard H, Rasmussen SK, Roberts TH, Hejgaard J (October 2000). “Inhibitory serpins from wheat grain with reactive centers resembling glutamine-rich repeats of prolamin storage proteins. Cloning and characterization of five major molecular forms”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (43): 33272–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M004633200. PMID 10874043.

- ^ a b Yoo BC, Aoki K, Xiang Y, Campbell LR, Hull RJ, Xoconostle-Cázares B, Monzer J, Lee JY, Ullman DE, Lucas WJ (November 2000). “Characterization of cucurbita maxima phloem serpin-1 (CmPS-1). A developmentally regulated elastase inhibitor”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (45): 35122–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M006060200. PMID 10960478.

- ^ la Cour Petersen M, Hejgaard J, Thompson GA, Schulz A (December 2005). “Cucurbit phloem serpins are graft-transmissible and appear to be resistant to turnover in the sieve element-companion cell complex”. Journal of Experimental Botany 56 (422): 3111–20. doi:10.1093/jxb/eri308. PMID 16246856.

- ^ Roberts TH, Hejgaard J (February 2008). “Serpins in plants and green algae”. Functional & Integrative Genomics 8 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1007/s10142-007-0059-2. PMID 18060440.

- ^ Lampl N, Alkan N, Davydov O, Fluhr R (May 2013). “Set-point control of RD21 protease activity by AtSerpin1 controls cell death in Arabidopsis”. The Plant Journal 74 (3): 498–510. doi:10.1111/tpj.12141. PMID 23398119.

- ^ Ahn JW, Atwell BJ, Roberts TH (2009). “Serpin genes AtSRP2 and AtSRP3 are required for normal growth sensitivity to a DNA alkylating agent in Arabidopsis”. BMC Plant Biology 9: 52. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-9-52. PMC 2689219. PMID 19426562.

- ^ a b Kang S, Barak Y, Lamed R, Bayer EA, Morrison M (June 2006). “The functional repertoire of prokaryote cellulosomes includes the serpin superfamily of serine proteinase inhibitors”. Molecular Microbiology 60 (6): 1344–54. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05182.x. PMID 16796673.

- ^ Irving JA, Cabrita LD, Rossjohn J, Pike RN, Bottomley SP, Whisstock JC (April 2003). “The 1.5 A crystal structure of a prokaryote serpin: controlling conformational change in a heated environment”. Structure 11 (4): 387–97. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(03)00057-1. PMID 12679017.

- ^ Fulton KF, Buckle AM, Cabrita LD, Irving JA, Butcher RE, Smith I, Reeve S, Lesk AM, Bottomley SP, Rossjohn J, Whisstock JC (March 2005). “The high resolution crystal structure of a native thermostable serpin reveals the complex mechanism underpinning the stressed to relaxed transition”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 (9): 8435–42. doi:10.1074/jbc.M410206200. PMID 15590653.

- ^ Turner PC, Moyer RW (September 2002). “Poxvirus immune modulators: functional insights from animal models”. Virus Research 88 (1-2): 35–53. doi:10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00119-3. PMID 12297326.

- ^ a b Richardson J, Viswanathan K, Lucas A (2006). “Serpins, the vasculature, and viral therapeutics”. Frontiers in Bioscience 11: 1042–56. doi:10.2741/1862. PMID 16146796.

- ^ a b Jiang J, Arp J, Kubelik D, Zassoko R, Liu W, Wise Y, Macaulay C, Garcia B, McFadden G, Lucas AR, Wang H (November 2007). “Induction of indefinite cardiac allograft survival correlates with toll-like receptor 2 and 4 downregulation after serine protease inhibitor-1 (Serp-1) treatment”. Transplantation 84 (9): 1158–67. doi:10.1097/01.tp.0000286099.50532.b0. PMID 17998872.

- ^ Dai E, Guan H, Liu L, Little S, McFadden G, Vaziri S, Cao H, Ivanova IA, Bocksch L, Lucas A (May 2003). “Serp-1, a viral anti-inflammatory serpin, regulates cellular serine proteinase and serpin responses to vascular injury”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (20): 18563–72. doi:10.1074/jbc.M209683200. PMID 12637546.

- ^ Turner PC, Sancho MC, Thoennes SR, Caputo A, Bleackley RC, Moyer RW (August 1999). “Myxoma virus Serp2 is a weak inhibitor of granzyme B and interleukin-1beta-converting enzyme in vitro and unlike CrmA cannot block apoptosis in cowpox virus-infected cells”. Journal of Virology 73 (8): 6394–404. PMC 112719. PMID 10400732.

- ^ Munuswamy-Ramanujam G, Khan KA, Lucas AR (December 2006). “Viral anti-inflammatory reagents: the potential for treatment of arthritic and vasculitic disorders”. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders Drug Targets 6 (4): 331–43. doi:10.2174/187153006779025720. PMID 17214579.

- ^ Renatus M, Zhou Q, Stennicke HR, Snipas SJ, Turk D, Bankston LA, Liddington RC, Salvesen GS (July 2000). “Crystal structure of the apoptotic suppressor CrmA in its cleaved form”. Structure 8 (7): 789–97. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00165-9. PMID 10903953.

外部リンク

[編集]- 蛋白質構造データバンク 今月の分子53:セルピン(Serpins)

- Merops protease inhibitor claudication (Family I4)

- Serpins - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス

- James Whisstock laboratory モナシュ大学

- Jim Huntington laboratory ケンブリッジ大学

- Frank Church laboratory ノースカロライナ大学チャペルヒル校

- Paul Declerck laboratory ルーヴェン・カトリック大学

- Tom Roberts laboratory シドニー大学

- Robert Fluhr laboratory ワイツマン科学研究所

- Peter Gettins laboratory イリノイ大学シカゴ校

- 血液中のセリンプロテイナーゼインヒビター・スーパファミリー