六脚類

| 六脚類 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| 地質時代 | ||||||||||||

| デボン紀[1] - 現世 | ||||||||||||

| 分類 | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| 学名 | ||||||||||||

| Hexapoda Latreille, 1825 | ||||||||||||

| 和名 | ||||||||||||

| 六脚類 | ||||||||||||

| 英名 | ||||||||||||

| hexapod | ||||||||||||

| 綱 | ||||||||||||

六脚類(ろっきゃくるい、hexapod, 学名: Hexapoda)は、節足動物を大きく分けた分類群の1つ、分類学上は一般に六脚亜門とされる。3対6本の脚を胸部に持ち、昆虫およびそれと共通点の多い内顎類で構成される[2][3]。

内顎類(内顎綱)のトビムシ目・カマアシムシ目・コムシ目はかつて昆虫(昆虫綱)に含まれる経緯があった。後に昆虫と区別され、この六脚類の分類体系に至った[4]。これにより、六脚類は「古典的な昆虫類」に相当で、ときには「広義の昆虫類」扱いともされる。

2010年代現在、六脚類と他の節足動物の系統関係については、側系統の甲殻類から派生し、共に汎甲殻類(Pancrustacea)を構成する説が広く認められる[3]。この場合、汎甲殻類は亜門扱いされ、そのうち六脚類は六脚上綱もしくは六脚綱とされることもある[5][6]。

形態

[編集]

外骨格に覆われた体は数多くの体節からなり、順に頭部・胸部・腹部という3つの合体節を構成する。原則として頭部は1対の触角と数対の顎、胸部は3対の脚をもつ。胸部と腹部の体節は背面が背板(tergite, 胸部の場合は notum[7])に、腹面が腹板(sternite)に、左右が側板(pleura, pleuron, pleurite)に覆われている。

頭部

[編集]-

トビムシの単眼

頭部(head)は先節と直後5節の体節の融合でできた合体節で[8]、基本として触角・大顎・小顎・下唇という4対の付属肢(関節肢)をもつ。昆虫の場合、頭部は基本として側眼(lateral eye)由来の1対の複眼(compound eye)を左右に、中眼(median eye)由来の3つの単眼(ocellus, 複: ocelli)を背面中央に備わる。完全変態をする昆虫の幼虫は、往々にして複眼由来の側単眼(stemma)を1対上もつ。内顎類の場合、トビムシは側単眼を最多8対もち[5]、コムシとカマアシムシは眼を欠く[4]。

- 先節 (ocular somite)

- 第1体節 (somite I)

- 第2体節 (somite II)

- 第3体節 (somite III)

- 第4体節 (somite IV)

- 第5体節 (somite V)

胸部

[編集]

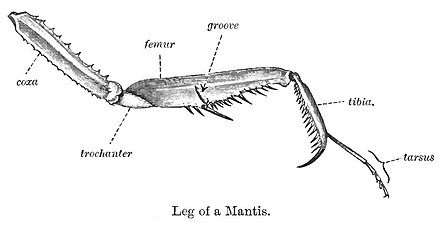

胸部(thorax)は3節の胸節(第6-8体節、順に前胸 prothorax・中胸 mesothorax・後胸 metathorax)からなり、それに応じて計3対6本の脚をもつ。脚は順に前脚 (foreleg)・中脚 (midleg)・後脚 (hindleg) と呼ばれ、付け根から先端まで基節 (coxa)・転節 (trochanter)・腿節 (femur)・脛節 (tibia)・跗節 (tarsus) という5節の肢節に分かれている。昆虫の場合、跗節は更に数節の跗小節 (tarsomere) に細分される。脚はいずれも単枝型で、既知唯一の例外は、基節の外側に「coxal stylus」という外葉由来とされる構造体をもつイシノミの中脚と後脚(または後脚のみ)である[17]。脚の基節背面に隣接した側板は、元々脚の一部(亜基節 subcoxa)とも考えられる[18][19][20]。基本として歩行に適した歩脚状だが、把握に適した鎌状(亜鋏状)や遊泳に適したオール状など、ある程度の特化が幾つかの分類群に見られる。

有翅昆虫[21](pterygotes、winged insects)の場合、4枚の翅は第2と第3胸節の背板と側板の間に1対ずつ備わる。なお、翅を二次的に退化させ、翅が1対のみもしくは欠けている有翅昆虫もある(双翅目、アリの働きアリ、カカトアルキ、シラミ、ノミなど)。この翅の由来は議論的で、背板の一部・側板の一部・側板含めて脚の一部・背板と脚/側板由来の部分を兼ね備えるなど、様々な解釈を提唱される[22][23][24][25][20][26]。

腹部

[編集]腹部(abdomen)は祖先形質として11節の腹節(第9-20体節)をもつ[2][27]。生殖孔(gonopore)は腹側にあり、雄では第10腹節、雌では第10腹節と第9腹節の間に開く[27]。肛門の周辺、すなわち末端の背面と左右はそれぞれ肛上板(epiproct)と肛側片(paraproct)をもつ場合がある[28]が、節足動物として一般的な尾節(telson)らしき構造はほぼ見当たらない[29](一説では肛上板は尾節由来の構造[28])。また、トビムシの腹部は6腹節のみをもち、昆虫とコムシの腹部は第11腹節が不明瞭のため、外見上は10腹節に見える[30][28]。

-

ヘビトンボの1種 Corydalus cornutus の雄性器(g:生殖肢)

腹部の付属肢はほとんどが痕跡的、あるいは完全に退化消失するが、往々にして付属肢由来の構造があり、以下の例が挙げられる。

- 腹刺 (abdominal stylus)

生態

[編集]

-

洞窟性のタマキノコムシの1種Leptodirus hochenwartii

内顎類は多くが土壌生物で、湿潤な生息環境を好んでいる。本群の中で最も多様化したのはトビムシで、土壌だけでなく、林冠・潮だまり・氷河・洞窟にも生息している[2]。コムシは捕食性であるが、トビムシは腐植質や真菌などを主食とし、土壌生態系の重要な分解者である[36]。カマアシムシの食性は明らかになっていないが、飼育下では菌根やダニの遺骸を摂食し[37]、一部の種では口器を真菌の菌糸に差し込んで、その内部組織を摂る行動が確認される[38]。

昆虫、特に有翅昆虫は多様なニッチ(生態的地位)へ進出し、地上・土中・洞窟・極地・砂漠・陸水・空中・寄生など全ての陸上生態系で優勢を占める[39]。食性も口器の多様性に現れるように、肉食性・植物食性・菌食性・腐食性・腐植食性・吸血性など様々である。様々な生態系と深く関わり、捕食者・分解者・送粉者・他の生物の餌などとして重要視される。有翅昆虫は多様な環境へ進出できたのは、複数の跗小節に分かれて特化した跗節(幅広い運動性を生じ、様々な表面に登れる)・複雑な交尾器で体内受精と産卵を行う(受精の成功率を上げて、狭い隙間で卵を産める)・飛翔能力をもつ(捕食者から逃げやすく、別の場所へ到達しやすくなる)、などの特徴に大きく関与すると考えられる[2]。

一方、海棲の六脚類は非常に少ない。海岸に生息するのはトビムシやイシノミなどが挙げられる[40]が、外洋に進出するのはウミアメンボ属の5種しかない[41]。これは逆に海棲種がほとんどで、陸生種が少ない甲殻類とは対照的である。

繁殖

[編集]-

飛行しながら交尾するハナアブの1種 Simosyrphus grandicornis

-

護卵するハサミムシ

-

幼虫の世話をするアリ

繁殖行動については、多くの内顎類・イシノミ・シミのように受精は精莢の受け渡しを通じて行うものと、有翅昆虫のように交尾器の接触を通じて交尾を行う配偶行動がある[2]。トビムシと一部の昆虫においては独特な求愛行動が見られ、特に昆虫の中ではコオロギやセミのように音を鳴いて異性を引き寄せるものがある。卵や幼虫を育てる保育行動をもつものもあり、中でも社会性昆虫が代表的である。

基本としては卵生で有性生殖を行うが、アブラムシのように卵胎生と単為生殖が行える例も見られる。

発育

[編集]

他の節足動物と同様、六脚類は脱皮で成長する。基本として成体と同様な体節数をもって生まれるが、カマアシムシは多足類のように増節変態を行い、腹節は脱皮を経て増やす[4]。昆虫の場合、未成熟の個体は幼生/幼虫(larva)もしくは若虫(nymph)、性成熟した個体は成虫(imago)、成虫になる脱皮過程は羽化(eclosion)と呼ばれる。

内顎類・イシノミ・シミでは成長過程で形態上の著しい変化はないが、有翅昆虫ではある程度の変化が見られ、この現象は変態(metamorphosis)と呼ばれる。不完全変態昆虫(=完全変態昆虫以外の有翅昆虫)では不完全変態(hemimetabolism、incomplete metamorphosis)を行い、幼虫は成虫に比べて翅は未成熟などの違いが見られるが、大まかな形態は成虫と共通している。このような幼虫は、「若虫」(nymph)として後述の完全変態昆虫の幼虫から区別される[42]。若虫は数回の脱皮を経て成長し続け、通常は終齢若虫が脱皮を迎えると成虫になるが、カゲロウでは終齢若虫と成虫の間には亜成虫(subimago)という特殊な段階が存在する[43]。

完全変態昆虫(holometabolous insects、Endopterygota)では完全変態(holometabolism、complete metamorphosis)を行い、幼虫(larva)は成虫とは大きく異なった形態をもつ。成虫らしき翅や脚などの形質は幼虫の外見で見当たらず、成虫原基(imaginal disc)として体内に潜んでいる。幼虫は数回の脱皮を経て成長し続け、終齢幼虫は脱皮の前に前蛹(prepupa)となり、脱皮を迎えると蛹(pupa)という摂食せず、運動性の低いもしくは欠く[2]段階になる(蛹化 pupation)。幼虫の構造は蛹の中で成虫の構造へ再構成され、成虫原基が対応した成虫構造になる。中身が成熟した蛹は、羽化で成虫になる。

起源と進化

[編集]

上:ムカシアミバネムシのステノディクティア Stenodictya lobata

Misof et al. 2014 によって行われる大規模な分子系統解析(1 Kiteプロジェクト[44][45])によると、六脚類はおよそ4億7,900万年前のオルドビス紀、昆虫はおよそ4億4,000万年前のシルル紀、有翅昆虫はおよそ4億600万年前のデボン紀に起源とされる[45]。一方で、昆虫はおよそ4億7,500万年前で内顎類と分岐し、有翅昆虫はおよそ4億1300万年前に起源とする解析結果もある[46]。

いずれの結果も、六脚類は陸生動物自体よりも早期な起源をもつことが示唆される。これにより、六脚類は甲殻類から派生しているという系統関係(汎甲殻類説、後述参照)に併せて、内顎類と昆虫類より基盤的な初期の六脚類は海棲動物であったと考えられる[2][46]。ウェールズのオルドビス紀の海成層であるCastle Bankからは六脚類らしき形態の節足動物化石が知られるものの、詳しい研究は行われていない[47]。六脚類はいつから上陸したのは不明だが、シルル紀で植物と共に陸上環境を適応放散し[45]、直後のデボン紀で昆虫は飛行能力を進化していたと考えられる[46]。

なお、六脚類の初期系統分化や翅の起源を示唆する確実な化石証拠は欠けている[2]。基盤的な六脚類や昆虫と解釈されたデボン紀の古生物はいくつかあるが、そのほとんどが不確実で、別生物の見間違いであったものすらあり、次の通りに挙げられる[48]。

- リニエラ(Rhyniella praecursor):トビムシとされ[49]、既知最古の確定的な六脚類化石として知られる[48]。

- リニオグナサ(Rhyniognatha hirsti)[50]:1対の大顎が見られる唯一の化石標本 NHML In. 38234 によって知られる。最初はリニエラの一部として記載されたが、後に有翅昆虫の新属新種として再記載され[51]、最古の有翅昆虫化石として広く知られていた。しかし Haug & Haug 2017 の再検証では同じ標本から発見された頭部構造により、昆虫ですらなく、むしろゲジ類のムカデであった可能性が浮かび上がる[48]。

- Eopterum devonicum と Eopteridium striatum:昆虫の翅として記載されたが、後に甲殻類の付属肢(基盤的なシャコ類の尾肢[52])だと判明した[53]。

- デヴォノヘキサポドゥス (Devonohexapodus bocksbergensis):基盤的な水生六脚類として記載されたが、Kühl & Rust 2009 の再検証によりウィンガートシェリクス(Wingertshellicus backesi)という明らかに別系統の節足動物のシノニムだと判明した[54][2]。

- Leverhulmia mariae[55]:多足類として記載されたが、後に昆虫(イシノミもしくはシミ)と見直された[56]。

- Strudiella devonica[57] :昆虫として記載されたが、保存状態は悪く、腐敗が進んだ別の節足動物の遺骸ともされる[58]。

- Bennettarthra annwnensis[59]:初期の大型六脚類とも考えられるが、化石が胸部や頭部を欠くため不確実[59]。

- ガスペ(カナダ)で発見された断片化石:イシノミ由来と考えられる[60]。

- ギルボア(アメリカ)で発見された様々な節足動物の断片化石:一部のものは昆虫(イシノミもしくはシミ)由来と思われるが、確実でない[61]。

既知最古かつ確定的な有翅昆虫は、石炭紀前期(およそ3億2,500万年前)の Delitzschala bitterfeldensis という絶滅したムカシアミバネムシ目(Palaeodictyoptera)の1種である。ただし、本種が生息した地質時代は前述の化石証拠と分子時計解析に示唆される結果より数百万年ほど晩期である。この大きな地質時代のギャップは、「Hexapoda gap」として知られている[57]。

旧翅類・多新翅類・完全変態昆虫はデボン紀後期 - 石炭紀前期で適応拡散したとされる。これは同時期で昆虫の栄養源とニッチを構成した種子植物の適応拡散に関与すると考えられ、多新翅類と完全変態昆虫の特化した口器にも反映される[46]。また、石炭紀後期ではオオトンボ目(Meganisoptera)という既知最大級の昆虫を含む絶滅群も現れた[62]。完全変態昆虫の多くの系統群は石炭紀後期に起源とされるが、顕著な多様化は被子植物の適応拡散と同時期である白亜紀前期から始まったとされる[45]。

分類

[編集]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2019年現在で有力視され、節足動物における六脚類の系統的位置[3]。青い枠以内の分類群(六脚類以外の汎甲殻類)は側系統群の甲殻類に属する。 |

節足動物内での六脚類の位置づけは、昆虫の起源を理解するための大きな指標であり、古くから多くの議論が繰り広げられた。様々な系統仮説が提唱され、例えば多足類の派生群[63]、甲殻類の派生群、もしくはそのどちらが六脚類の姉妹群になる、などが挙げられる[64]。

古くは多くの形態学上の共通点、例えば頭部の付属肢構成(上述参照)・マルピーギ管・気管系・精莢を作ることなどに基づいて、六脚類は多足類に近縁で、まとめて無角類(Atelocerata、または気門類 Tracheata)になる説が主流であった[65][2]。しかし2000年代をはじめとして、六脚類と多足類の類縁関係は多くの分子系統解析に否定的とされ、代わりに六脚類と甲殻類の類縁関係、特に六脚類は側系統群の甲殻類から派生している説を根強く支持している[66][67][68][69][70][71][2][72][27][3][6]。この類縁関係は分子系統学だけでなく、神経解剖学などの形態学の再検証からも支持が得られている[73][74][3]。六脚類と甲殻類を併せた単系統群は、汎甲殻類(Pancrustacea、または八分錘類 Tetraconata)と呼ばれる[3]。

2000年代以降、汎甲殻類説が広く認められるようになり、特に2010年代後期以降では、六脚類の姉妹群になる甲殻類としてムカデエビが有力候補と見なされる(共にLabiocaridaをなす)[72][3][27]。これにより、前述の六脚類と多足類の多くの共通点は、単に陸上生活への適応でそれぞれ独自に獲得した特徴、すなわち収斂進化の結果とも見直されるようになった[2]。

下位分類

[編集]

かつて、全ての六脚類は昆虫綱に分類され、内顎類・イシノミ目・シミ目からなる無翅亜綱(Apterygota、無翅昆虫 apterygotes)[4]と、残りの祖先形質として翅をもつ昆虫からなる有翅亜綱(Pterygota、有翅昆虫 pterygotes)で大別された。後に内顎類は昆虫から区別され、内顎綱(Entognatha)と昆虫綱(Insecta、または外顎綱 Ectognatha)で大別する六脚類の分類体系に至り、有翅昆虫は昆虫綱の1下綱(有翅下綱)で、無翅昆虫は単にそれ以外の六脚類を指す便宜上の総称となった。

ただし、内顎類の単系統性が後に疑問視され、コムシ目は昆虫綱の姉妹群(共に有尾類[75] Cercophora をなす[2])であることが分子系統学と比較発生学的解析に示唆される[75][45][3]。昆虫綱の内部系統関係は、1KITEプロジェクト[45]などによって有力な解析結果が与えられ、例えばかつて議論的であった多新翅類の単系統性が認められるようになり、系統位置が不確実なジュズヒゲムシをも含むことが判明した[2][3]。多新翅類におけるジュズヒゲムシの姉妹群、および旧翅類と準新翅類の単系統性はまだ議論の余地がある[45][46]が、他の節足動物の高次系統群に比べても、六脚類の内部系統関係は比較的安定な解析結果が得られている[3]。

| 六脚亜門 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

以下の下位分類群一覧は、現世に存続し、目階級までの分類群のみを挙げる。絶滅群をも含んだ詳細な分類は「昆虫の分類#下位分類」を参照のこと。

- 六脚亜門 Hexapoda - 六脚類(=広義の昆虫類)。後大脳性体節は付属肢を持たない間挿体節。大顎は大顎髭を持たない。第2小顎は癒合して下唇となる。第6-8体節は6本の脚を有する胸部をなす。

- 内顎綱 Entognatha - 内顎類。顎の基部は頭部に内蔵される。触角はすべての関節に筋肉を持つ。脚の跗節は1節のみからなる[4]。複眼とマルピーギ管は退化的もしくは欠如[2]。湿潤な環境を好む小型土壌生物として知られ[4]、非単系統群(コムシ目は昆虫綱の姉妹群)ともされる[45]。以下3つの目は、かつて昆虫綱に含まれ、後にこの綱に含めるようになったが、それぞれ独立の綱と扱われる場合もある[4][5]。

- 昆虫綱 Insecta(=外顎綱 Ectognatha)- 昆虫(=狭義の昆虫類、真正昆虫類)。顎は基部から頭部の外側で露出し、触角は基部2節のみ筋肉をもつ[2][4]。跗節は複数の跗小節に細分される[2]。第8-9腹節の付属肢(生殖肢)は雌性器をなす[2]。高度に多様化しており、動物全般の中でも種類が最も富んだ綱である[45]。

- 単関節丘亜綱 Monocondylia - 大顎は1つの関節丘で頭部に固定される[2]。

- イシノミ目(古顎目)Archaeognatha(=Microcoryphia)- イシノミ。かつてシミと共にThysanura目に分類された。

- 双関節丘亜綱 Dicondylia - 大顎は2つの関節丘で頭部に固定される[2]。腹部は腹刺を欠く[45]。

- シミ目(総尾目、房尾目)Zygentoma - シミ。かつてイシノミと共にThysanura目に分類された。

- 有翅下綱 Pterygota - 有翅昆虫。祖先形質として翅をもつ。昆虫全種の中でおそよ99%がここに含まれる[2]。

- 旧翅節 Paleoptera - 旧翅類。翅を胸部の後側へと畳めない。触角はごく短く、幼虫は水生。単系統性はやや不確実[45][2]。

- 新翅節 Neoptera - 翅を胸部の後側へと畳める[2]。

- 多新翅亜節 Polyneoptera - 多新翅類

- ジュズヒゲムシ目(絶翅目)Zoraptera - ジュズヒゲムシ

- ハサミムシ目(革翅目)Dermaptera - ハサミムシ

- カワゲラ目 Plecoptera - カワゲラ

- バッタ目(直翅目)Orthoptera - バッタ、コオロギ、キリギリス、カマドウマ、コロギスなど。

- マントファスマ目(カカトアルキ目)Mantophasmatodea - カカトアルキ(マントファスマ)

- ガロアムシ目(非翅目)Grylloblattodea - ガロアムシ

- シロアリモドキ目(紡脚目)Embioptera - シロアリモドキ

- ナナフシ目 Phasmatodea - ナナフシ

- ゴキブリ目 Blattodea - ゴキブリ、シロアリ。後者はかつてシロアリ目(等翅目 Isoptera)として区別された。

- カマキリ目(蟷螂目)Mantodea - カマキリ

- 準新翅亜節 Paraneoptera - 準新翅類。非単系統(咀顎目は完全変態昆虫の姉妹群)ともされる[45]。

- 内翅亜節 Endopterygota(=完全変態亜節 Holometabola)- 貧新翅類/完全変態昆虫。蛹化をし、完全変態を行う。

- ハチ目(膜翅目)Hymenoptera - ハチ、アリ。

- ラクダムシ目 Raphidiodea - ラクダムシ。かつて脈翅目に含まれた。

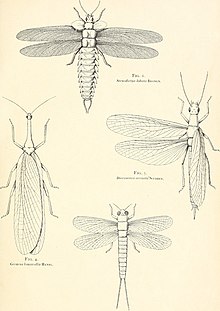

- ヘビトンボ目(広翅目)Megaloptera - ヘビトンボ。かつて脈翅目に含まれた。

- アミメカゲロウ目(脈翅目)Neuroptera - ウスバカゲロウ、クサカゲロウ、カマキリモドキ、ツノトンボなど。

- ネジレバネ目(撚翅目)Strepsiptera - ネジレバネ

- コウチュウ目(甲虫目、鞘翅目)Coleoptera - 甲虫

- トビケラ目(毛翅目)Trichoptera - トビケラ

- チョウ目(ガ目、鱗翅目)Lepidoptera - ガ、チョウ。

- シリアゲムシ目(長翅目)Mecoptera - シリアゲムシ、ガガンボモドキ。ノミ目を除いた側系統群とされる[45]。

- ノミ目(隠翅目)Siphonaptera - ノミ。系統的に長翅目から分岐したとされる[45]。

- ハエ目(双翅目)Diptera - ガガンボ、カ、ブユ、アブ、ハエなど。

- 多新翅亜節 Polyneoptera - 多新翅類

- 単関節丘亜綱 Monocondylia - 大顎は1つの関節丘で頭部に固定される[2]。

出典および脚注

[編集]- ^ a b 分子系統解析によるとオルドビス紀(およそ4億7900万年前)に起源とされる。後述参照。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Beutel, Rolf G; Yavorskaya, Margarita I; Mashimo, Yuta; Fukui, Makiko; Meusemann, Karen (2017-01). “The Phylogeny of Hexapoda (Arthropoda) and the Evolution of Megadiversity” (英語). Proceedings of the Arthropodan Embryological Society of Japan.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Giribet, Gonzalo; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2019-06-17). “The Phylogeny and Evolutionary History of Arthropods”. Current Biology 29 (12): R592–R602. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.057. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i “The Hexapods”. projects.ncsu.edu. 2019年8月22日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Checklist of the Collembola: Collembola”. www.collembola.org. 2019年8月22日閲覧。

- ^ a b 大塚攻、田中隼人「顎脚類(甲殻類)の分類と系統に関する研究の最近の動向」『タクサ:日本動物分類学会誌』第48巻、日本動物分類学会、2020年、49–62頁、doi:10.19004/taxa.48.0_49。

- ^ “Notum definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary”. 2022年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Hughes, Cynthia L.; Kaufman, Thomas C. (2002-3). “Exploring the myriapod body plan: expression patterns of the ten Hox genes in a centipede”. Development (Cambridge, England) 129 (5): 1225–1238. ISSN 0950-1991. PMID 11874918.

- ^ Smith, Frank W.; Goldstein, Bob (2017-05-01). “Segmentation in Tardigrada and diversification of segmental patterns in Panarthropoda”. Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (3): 328–340. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2016.10.005. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ a b Du, Xiaoliang; Yue, Chao; Hua, Baozhen (2009). “Embryonic development of the scorpionfly Panorpa emarginata Cheng with special reference to external morphology (Mecoptera: Panorpidae)” (英語). Journal of Morphology 270 (8): 984–995. doi:10.1002/jmor.10736. ISSN 1097-4687.

- ^ Ortega-Hernández, Javier; Janssen, Ralf; Budd, Graham E. (2017-05-01). “Origin and evolution of the panarthropod head – A palaeobiological and developmental perspective”. Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (3): 354–379. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2016.10.011. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ Posnien, Nico; Bucher, Gregor (2010-02-01). “Formation of the insect head involves lateral contribution of the intercalary segment, which depends on Tc-labial function”. Developmental Biology 338 (1): 107–116. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.010. ISSN 0012-1606.

- ^ Kaufman, Thomas C.; Hughes, Cynthia L. (2002-03-01). “Exploring the myriapod body plan: expression patterns of the ten Hox genes in a centipede” (英語). Development 129 (5): 1225–1238. ISSN 0950-1991. PMID 11874918.

- ^ “maxillary palpの意味・使い方”. eow.alc.co.jp. 2019年8月22日閲覧。

- ^ “maxillary palpの意味・使い方 - 英和辞典 WEBLIO辞書”. ejje.weblio.jp. 2019年8月22日閲覧。

- ^ “labial palpの意味・使い方 - 英和辞典 WEBLIO辞書”. ejje.weblio.jp. 2019年8月22日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Archaeognatha - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics”. www.sciencedirect.com. 2019年8月23日閲覧。

- ^ Coulcher, Joshua F.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Telford, Maximilian J. (2015-10-28). “Molecular developmental evidence for a subcoxal origin of pleurites in insects and identity of the subcoxa in the gnathal appendages” (英語). Scientific Reports 5 (1): 15757. doi:10.1038/srep15757. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4623811. PMID 26507752.

- ^ Kobayashi, Yukimasa (2018) (英語). The paracoxal suture in insect embryos: Its state and importance for understanding the basalmost podomeres. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.24495.64165.

- ^ a b Bruce, Heather S.; Patel, Nipam H. (2020-12). “Knockout of crustacean leg patterning genes suggests that insect wings and body walls evolved from ancient leg segments” (英語). Nature Ecology & Evolution 4 (12): 1703–1712. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-01349-0. ISSN 2397-334X.

- ^ デジタル大辞泉. “有翅昆虫(ユウシコンチュウ)とは”. コトバンク. 2019年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ Clark-Hachtel, Courtney M; Tomoyasu, Yoshinori (2016-02-01). “Exploring the origin of insect wings from an evo-devo perspective” (英語). Current Opinion in Insect Science 13: 77–85. doi:10.1016/j.cois.2015.12.005. ISSN 2214-5745.

- ^ Elias-Neto, Moysés; Belles, Xavier (2016-08-01). “Tergal and pleural structures contribute to the formation of ectopic prothoracic wings in cockroaches”. Royal Society Open Science 3 (8): 160347. doi:10.1098/rsos.160347. PMC 5108966. PMID 27853616.

- ^ Prokop, Jakub; Pecharová, Martina; Nel, André; Hörnschemeyer, Thomas; Krzemińska, Ewa; Krzemiński, Wiesław; Engel, Michael S. (2017-01-23). “Paleozoic Nymphal Wing Pads Support Dual Model of Insect Wing Origins” (English). Current Biology 27 (2): 263–269. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.11.021. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 28089512.

- ^ Linz, David M.; Tomoyasu, Yoshinori (2018-01-23). “Dual evolutionary origin of insect wings supported by an investigation of the abdominal wing serial homologs in Tribolium” (英語). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (4). doi:10.1073/pnas.1711128115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5789912. PMID 29317537.

- ^ Ohde, Takahiro; Mito, Taro; Niimi, Teruyuki (2022-02-21). “A hemimetabolous wing development suggests the wing origin from lateral tergum of a wingless ancestor” (英語). Nature Communications 13 (1): 979. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28624-x. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8861169. PMID 35190538.

- ^ a b c d Olesen, Jørgen; Pisani, Davide; Iliffe, Thomas M.; Legg, David A.; Palero, Ferran; Glenner, Henrik; Thomsen, Philip Francis; Vinther, Jakob et al. (2019-08-01). “Pancrustacean Evolution Illuminated by Taxon-Rich Genomic-Scale Data Sets with an Expanded Remipede Sampling” (英語). Genome Biology and Evolution 11 (8): 2055–2070. doi:10.1093/gbe/evz097.

- ^ a b c d e f Snodgrass, R. E. (2018-05-31) (英語). Principles of Insect Morphology. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501717918

- ^ Grimaldi, David; Engel, Michael S. (2005-05-16) (英語). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107268777

- ^ “Diplura (Insects)”. what-when-how.com. 2019年8月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b Boudinot, Brendon E. (2018-11-01). “A general theory of genital homologies for the Hexapoda (Pancrustacea) derived from skeletomuscular correspondences, with emphasis on the Endopterygota”. Arthropod Structure & Development 47 (6): 563–613. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2018.11.001. ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ “Terminalia / The Insects”. www.entomologa.ru. 2019年8月21日閲覧。

- ^ 冨田秀一郎; 畠山正統 (2017). 研究成果報告書 昆虫腹脚の多様性と進化の分子機構. 科学研究費助成事業 2021年1月6日閲覧。.

- ^ Suzuki, Y.; Palopoli, M. (2001). “Evolution of insect abdominal appendages: Are prolegs homologous or convergent traits?”. Development Genes and Evolution 211 (10): 486–492. doi:10.1007/s00427-001-0182-3. PMID 11702198.

- ^ Jacques Bitsch (2012). “The controversial origin of the abdominal appendage-like processes in immature insects: are they true segmental appendages or secondary outgrowths? (Arthropoda Hexapoda)”. Journal of Morphology 273 (8): 919-931. doi:10.1002/jmor.20031. PMID 22549894.

- ^ “The Hexapods”. projects.ncsu.edu. 2019年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ “proturans - Protura”. entomology.ifas.ufl.edu. 2019年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ “Gordon's Protura Page”. www.earthlife.net. 2019年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ Morris, Simon Conway (2007/11). “D. Grimaldi & M. S. Engel 2005. Evolution of the Insects. xv + 755 pp. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. Price £45.00, US $75.00 (hard covers). ISBN 0 521 82149 5.” (英語). Geological Magazine 144 (6): 1035–1036. doi:10.1017/S001675680700372X. ISSN 1469-5081.

- ^ Cheng, Lanna (2009-01-01). Resh, Vincent H.; Cardé, Ring T.. eds. Encyclopedia of Insects (Second Edition). San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 600–604. ISBN 9780123741448

- ^ “外洋に生きるウミアメンボ | 公益財団法人 藤原ナチュラルヒストリー振興財団”. fujiwara-nh.or.jp. 2019年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ Rédei, Dávid; Štys, Pavel (2016-7). “Larva, nymph and naiad - for accuracy's sake: Larva, nymph and naiad - for accuracy's sake” (英語). Systematic Entomology 41 (3): 505–510. doi:10.1111/syen.12177.

- ^ デジタル大辞泉,日本大百科全書(ニッポニカ). “亜成虫(アセイチュウ)とは”. コトバンク. 2019年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ “1 Kiteプロジェクト”. www.sugadaira.tsukuba.ac.jp. 2019年8月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Misof, B.; Liu, S.; Meusemann, K.; Peters, R. S.; Donath, A.; Mayer, C.; Frandsen, P. B.; Ware, J. et al. (2014-11-07). “Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution” (英語). Science 346 (6210): 763–767. doi:10.1126/science.1257570. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ a b c d e Wang, Yan-hui; Engel, Michael S.; Rafael, José A.; Wu, Hao-yang; Rédei, Dávid; Xie, Qiang; Wang, Gang; Liu, Xiao-guang et al. (2016-12-13). “Fossil record of stem groups employed in evaluating the chronogram of insects (Arthropoda: Hexapoda)”. Scientific Reports 6. doi:10.1038/srep38939. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5154178. PMID 27958352.

- ^ Botting, Joseph P.; Muir, Lucy A.; Pates, Stephen; McCobb, Lucy M. E.; Wallet, Elise; Willman, Sebastian; Zhang, Yuandong; Ma, Junye (2023-05-01). “A Middle Ordovician Burgess Shale-type fauna from Castle Bank, Wales (UK)”. Nature Ecology & Evolution 7 (5): 666–674. doi:10.1038/s41559-023-02038-4. ISSN 2397-334X.

- ^ a b c Haug, Joachim T.; Haug, Carolin (2017-05-30). “The presumed oldest flying insect: more likely a myriapod?” (英語). PeerJ 5: e3402. doi:10.7717/peerj.3402. ISSN 2167-8359.

- ^ E. A. Jarzembowski; Whalley, Paul (1981-05). “A new assessment of Rhyniella , the earliest known insect, from the Devonian of Rhynie, Scotland” (英語). Nature 291 (5813): 317–317. doi:10.1038/291317a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Tillyard, R. J. (1928). “Some Remarks on the Devonian Fossil Insects from the Rhynie Chert Beds, Old Red Sandstone” (英語). Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London 76 (1): 65–71. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1928.tb01188.x. ISSN 1365-2311.

- ^ David A. Grimaldi; Engel, Michael S. (2004-02). “New light shed on the oldest insect” (英語). Nature 427 (6975): 627–630. doi:10.1038/nature02291. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Klein, Carel von Vaupel; Charmantier-Daures, Mireille (2013-10-24) (英語). Treatise on Zoology - Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Crustacea, Volume 4 part A. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-474-4045-1

- ^ Schram, Frederick R. (1980). “Miscellaneous Late Paleozoic Malacostraca of the Soviet Union”. Journal of Paleontology 54 (3): 542–547. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ Kühl, Gabriele; Rust, Jes (2009-08-25). “Devonohexapodus bocksbergensis is a synonym of Wingertshellicus backesi (Euarthropoda) – no evidence for marine hexapods living in the Devonian Hunsrück Sea”. Organisms Diversity & Evolution 9 (3): 215–231. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2009.03.002. ISSN 1439-6092.

- ^ Anderson, Lyall I.; Trewin, Nigel H. (2003). “An Early Devonian arthropod fauna from the Windyfield cherts, Aberdeenshire, Scotland” (英語). Palaeontology 46 (3): 467–509. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00308. ISSN 1475-4983.

- ^ Fayers, Stephen R.; Trewin, Nigel H. (2005). “A Hexapod from the Early Devonian Windyfield Chert, Rhynie, Scotland” (英語). Palaeontology 48 (5): 1117–1130. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2005.00501.x. ISSN 1475-4983.

- ^ a b Nel, André; Prestianni, Cyrille; Olive, Sébastien; Lafaite, Patrick; Gueriau, Pierre; Denayer, Julien; Lagebro, Linda; D’Haese, Cyrille et al. (2012-08). “A complete insect from the Late Devonian period” (英語). Nature 488 (7409): 82–85. doi:10.1038/nature11281. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Willmann, Rainer; Bradler, Sven; Wedmann, Sonja; Rust, Jes; Koch, Markus; Hegna, Thomas A.; Charbonnier, Sylvain; Beutel, Rolf G. et al. (2013-02). “Is Strudiella a Devonian insect?” (英語). Nature 494 (7437): E3–E4. doi:10.1038/nature11887. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ a b Fayers, S. R.; Trewin, N. H.; Morrissey, L. (2010-05). “A large arthropod from the Lower Old Red Sandstone (Early Devonian) of Tredomen Quarry, south Wales: ARTHROPOD FROM THE LOWER ORS” (英語). Palaeontology 53 (3): 627–643. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00951.x.

- ^ Hueber, Francis M.; Beall, Bret S.; Labandeira, Conrad C. (1988-11-11). “Early Insect Diversification: Evidence from a Lower Devonian Bristletail from Québec” (英語). Science 242 (4880): 913–916. doi:10.1126/science.242.4880.913. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Norton, Roy A.; Smith, Edward Laidlaw; Rolfe, W. D. Ian; Grierson, James D.; Bonamo, Patricia M.; Shear, William A. (1984-05-04). “Early Land Animals in North America: Evidence from Devonian Age Arthropods from Gilboa, New York” (英語). Science 224 (4648): 492–494. doi:10.1126/science.224.4648.492. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17753774.

- ^ Hurrell, Stephen (英語). Ancient Life's Gravity and its Implications for the Expanding Earth.

- ^ Minelli, Alessandro (2011-03-21) (英語). Treatise on Zoology - Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Myriapoda. BRILL. ISBN 9789004156111

- ^ Edgecombe, Gregory D. (2018年). “2 The Arthropoda : A PhylogeneticFramework” (英語). www.semanticscholar.org. 2019年8月22日閲覧。

- ^ Kraus, O. (1998). Fortey, R. A.; Thomas, R. H.. eds (英語). Arthropod Relationships. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 295–303. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-4904-4_22. ISBN 9789401149044

- ^ Shultz J. W.; Regier J. C. (2000-05-22). “Phylogenetic analysis of arthropods using two nuclear protein–encoding genes supports a crustacean + hexapod clade”. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 267 (1447): 1011–1019. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1104. PMC 1690640. PMID 10874751.

- ^ Giribet, Gonzalo; Ribera, Carles (2000). “A Review of Arthropod Phylogeny: New Data Based on Ribosomal DNA Sequences and Direct Character Optimization” (英語). Cladistics 16 (2): 204–231. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2000.tb00353.x. ISSN 1096-0031.

- ^ Frati, Francesco; Dallai, Romano; Carapelli, Antonio; Boore, Jeffrey L.; Spinsanti, Giacomo; Nardi, Francesco (2003-03-21). “Hexapod Origins: Monophyletic or Paraphyletic?” (英語). Science 299 (5614): 1887–1889. doi:10.1126/science.1078607. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 12649480.

- ^ Regier, Jerome C.; Shultz, Jeffrey W.; Kambic, Robert E. (2005-02-22). “Pancrustacean phylogeny: hexapods are terrestrial crustaceans and maxillopods are not monophyletic”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 272 (1561): 395–401. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2917. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1634985. PMID 15734694.

- ^ Cunningham, Clifford W.; Martin, Joel W.; Wetzer, Regina; Bernard Ball; Hussey, April; Zwick, Andreas; Shultz, Jeffrey W.; Regier, Jerome C. (2010-02). “Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences” (英語). Nature 463 (7284): 1079–1083. doi:10.1038/nature08742. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Zaharoff, Alexander K.; Lindgren, Annie R.; Wolfe, Joanna M.; Oakley, Todd H. (2013-01-01). “Phylotranscriptomics to Bring the Understudied into the Fold: Monophyletic Ostracoda, Fossil Placement, and Pancrustacean Phylogeny” (英語). Molecular Biology and Evolution 30 (1): 215–233. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss216. ISSN 0737-4038.

- ^ a b Schwentner, Martin; Combosch, David J.; Pakes Nelson, Joey; Giribet, Gonzalo (2017-6). “A Phylogenomic Solution to the Origin of Insects by Resolving Crustacean-Hexapod Relationships” (英語). Current Biology 27 (12): 1818–1824.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.040.

- ^ Richter, Stefan (2002-01-01). “The Tetraconata concept: hexapod-crustacean relationships and the phylogeny of Crustacea”. Organisms Diversity & Evolution 2 (3): 217–237. doi:10.1078/1439-6092-00048. ISSN 1439-6092.

- ^ Wolff, Gabriella Hannah; Thoen, Hanne Halkinrud; Marshall, Justin; Sayre, Marcel E; Strausfeld, Nicholas James (2017-09-26). Scott, Kristin. ed. “An insect-like mushroom body in a crustacean brain”. eLife 6: e29889. doi:10.7554/eLife.29889. ISSN 2050-084X.

- ^ a b c “原始的昆虫系統群の口器の進化-比較発生学的アプローチ-”. KAKEN. 2019年8月23日閲覧。