利用者:加藤勝憲/トランジスター集積度

トランジスタ数とは、電子デバイス(通常は1つの基板または「チップ」)内のトランジスタ数のことである。集積回路の複雑さを示す最も一般的な尺度である(ただし、最近のマイクロプロセッサのトランジスタの大部分は、同じメモリセル回路を何度も複製したキャッシュメモリに含まれている)。しかし、トランジスタ数はチップの面積に正比例するため、対応する製造技術の先進性を表すものではない。

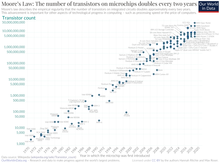

MOSトランジスタ数が増加する速度は、一般にムーアの法則に従っている。ムーアの法則では、トランジスタ数は約2年ごとに2倍になるとされている[1]。しかし、トランジスタ数はチップの面積に正比例するため、対応する製造技術がどれほど進んでいるかを示すものではない。これをよりよく示すのは、トランジスタ密度(チップの面積に対するトランジスタ数の比率)である。

2023年現在、フラッシュ・メモリで最もトランジスタ数が多いのは、マイクロン・テクノロジ社の2テラバイト(3D積層)16ダイ、232層のV-NANDフラッシュ・メモリ・チップで、5.3兆個の浮遊ゲートMOSFETを搭載している(1トランジスタあたり3ビット)。

2020年現在、シングルチッププロセッサーで最もトランジスタ数が多いのは、セレブラス社のディープラーニングプロセッサー「Wafer Scale Engine 2」だ。TSMCの7nm FinFETプロセスで製造され、ウェハー上の84の露出フィールド(ダイ)に2兆6000億個のMOSFETを搭載している[2][3][4][5]。

2024年現在、最もトランジスタ数の多いGPUはNvidiaのGB200 Grace Blackwellで、TSMCの4nmプロセスで製造され、合計2080億個のMOSFETを搭載している。

2023年現在、消費者向けマイクロプロセッサーで最もトランジスタ数が多いのは、アップル社のARMベースのデュアルダイM2 Ultraシステム・オン・チップの1,340億トランジスタで、TSMCの5nm半導体製造プロセスを使って製造されている[6]。

| Year | Component | Name | Number of MOSFETs (in trillions) |

Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Flash memory | Micron's V-NAND chip | 5.3 | stacked package of sixteen 232-layer 3D NAND dies |

| 2020 | any processor | Wafer Scale Engine 2 | 2.6 | wafer-scale design of 84 exposed fields (dies) |

| 2024 | GPU | GB200 Grace Blackwell | 0.208 | |

| 2023 | microprocessor (commercial) |

M2 Ultra | 0.134 | dual-die SoC; entire M2 Ultra is a multi-chip module |

| 2020 | DLP | Colossus Mk2 GC200 | 0.059 | An IPU in contrast to CPU and GPU |

In terms of computer systems that consist of numerous integrated circuits, the supercomputer with the highest transistor count 2016年現在[update] was the Chinese-designed Sunway TaihuLight, which has for all CPUs/nodes combined "about 400 trillion transistors in the processing part of the hardware" and "the DRAM includes about 12 quadrillion transistors, and that's about 97 percent of all the transistors."[7] To compare, the smallest computer, 2018年現在[update] dwarfed by a grain of rice, had on the order of 100,000 transistors. Early experimental solid-state computers had as few as 130 transistors but used large amounts of diode logic. The first carbon nanotube computer had 178 transistors and was a 1-bit one-instruction set computer, while a later one is 16-bit (its instruction set is 32-bit RISC-V though).

Estimates of the total numbers of transistors manufactured:

Transistor count

[編集]

Microprocessors

[編集]A microprocessor incorporates the functions of a computer's central processing unit on a single integrated circuit. It is a multi-purpose, programmable device that accepts digital data as input, processes it according to instructions stored in its memory, and provides results as output.

The development of MOS integrated circuit technology in the 1960s led to the development of the first microprocessors.[10] The 20-bit MP944, developed by Garrett AiResearch for the U.S. Navy's F-14 Tomcat fighter in 1970, is considered by its designer Ray Holt to be the first microprocessor.[11] It was a multi-chip microprocessor, fabricated on six MOS chips. However, it was classified by the Navy until 1998. The 4-bit Intel 4004, released in 1971, was the first single-chip microprocessor.

Modern microprocessors typically include on-chip cache memories. The number of transistors used for these cache memories typically far exceeds the number of transistors used to implement the logic of the microprocessor (that is, excluding the cache). For example, the last DEC Alpha chip uses 90% of its transistors for cache.[12]

GPUs

[編集]A graphics processing unit (GPU) is a specialized electronic circuit designed to rapidly manipulate and alter memory to accelerate the building of images in a frame buffer intended for output to a display.

The designer refers to the technology company that designs the logic of the integrated circuit chip (such as Nvidia and AMD). The manufacturer ("Fab.") refers to the semiconductor company that fabricates the chip using its semiconductor manufacturing process at a foundry (such as TSMC and Samsung Semiconductor). The transistor count in a chip is dependent on a manufacturer's fabrication process, with smaller semiconductor nodes typically enabling higher transistor density and thus higher transistor counts.

The random-access memory (RAM) that comes with GPUs (such as VRAM, SGRAM or HBM) greatly increases the total transistor count, with the memory typically accounting for the majority of transistors in a graphics card. For example, Nvidia's Tesla P100 has 15 billion FinFETs (16 nm) in the GPU in addition to 16 GB of HBM2 memory, totaling about 150 billion MOSFETs on the graphics card.[13] The following table does not include the memory. For memory transistor counts, see the Memory section below.

FPGA

[編集]A field-programmable gate array (FPGA) is an integrated circuit designed to be configured by a customer or a designer after manufacturing.

| FPGA | Transistor count | Date of introduction | Designer | Manufacturer | Process | Area | Transistor density, tr./mm2 | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtex | 70,000,000 | 1997 | Xilinx | |||||

| Virtex-E | 200,000,000 | 1998 | Xilinx | |||||

| Virtex-II | 350,000,000 | 2000 | Xilinx | 130 nm | ||||

| Virtex-II PRO | 430,000,000 | 2002 | Xilinx | |||||

| Virtex-4 | 1,000,000,000 | 2004 | Xilinx | 90 nm | ||||

| Virtex-5 | 1,100,000,000 | 2006 | Xilinx | TSMC | 65 nm | |||

| Stratix IV | 2,500,000,000 | 2008 | Altera | TSMC | 40 nm | [14] | ||

| Stratix V | 3,800,000,000 | 2011 | Altera | TSMC | 28 nm | [15] | ||

| Arria 10 | 5,300,000,000 | 2014 | Altera | TSMC | 20 nm | [16] | ||

| Virtex-7 2000T | 6,800,000,000 | 2011 | Xilinx | TSMC | 28 nm | [17] | ||

| Stratix 10 SX 2800 | 17,000,000,000 | TBD | Intel | Intel | 14 nm | 560 mm2 | 30,400,000 | [18][19] |

| Virtex-Ultrascale VU440 | 20,000,000,000 | Q1 2015 | Xilinx | TSMC | 20 nm | [20][21] | ||

| Virtex-Ultrascale+ VU19P | 35,000,000,000 | 2020 | Xilinx | TSMC | 16 nm | 900 mm2 [注釈 1] | 38,900,000 | [22][23][24] |

| Versal VC1902 | 37,000,000,000 | 2H 2019 | Xilinx | TSMC | 7<span typeof="mw:Entity" id="mwGnQ"> </span>nm | [25][26][27] | ||

| Stratix 10 GX 10M | 43,300,000,000 | Q4 2019 | Intel | Intel | 14<span typeof="mw:Entity" id="mwGoc"> </span>nm | 1,400 mm2 [注釈 1] | 30,930,000 | [28][29] |

| Versal VP1802 | 92,000,000,000 | 2021 ?[注釈 2] | Xilinx | TSMC | 7<span typeof="mw:Entity" id="mwGp8"> </span>nm | [30][31] |

Memory

[編集]Semiconductor memory is an electronic data storage device, often used as computer memory, implemented on integrated circuits. Nearly all semiconductor memories since the 1970s have used MOSFETs (MOS transistors), replacing earlier bipolar junction transistors. There are two major types of semiconductor memory: random-access memory (RAM) and non-volatile memory (NVM). In turn, there are two major RAM types: dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) and static random-access memory (SRAM), as well as two major NVM types: flash memory and read-only memory (ROM).

Typical CMOS SRAM consists of six transistors per cell. For DRAM, 1T1C, which means one transistor and one capacitor structure, is common. Capacitor charged or not[要説明] is used to store 1 or 0. In flash memory, the data is stored in floating gates, and the resistance of the transistor is sensed[要説明] to interpret the data stored. Depending on how fine scale the resistance could be separated[要説明], one transistor could store up to three bits, meaning eight distinctive levels of resistance possible per transistor. However, a finer scale comes with the cost of repeatability issues, and hence reliability. Typically, low grade 2-bits MLC flash is used for flash drives, so a 16 GB flash drive contains roughly 64 billion transistors.

For SRAM chips, six-transistor cells (six transistors per bit) was the standard. DRAM chips during the early 1970s had three-transistor cells (three transistors per bit), before single-transistor cells (one transistor per bit) became standard since the era of 4 Kb DRAM in the mid-1970s.[32][33] In single-level flash memory, each cell contains one floating-gate MOSFET (one transistor per bit),[34] whereas multi-level flash contains 2, 3 or 4 bits per transistor.

Flash memory chips are commonly stacked up in layers, up to 128-layer in production,[35] and 136-layer managed,[36] and available in end-user devices up to 69-layer from manufacturers.

| Chip name | Capacity (bits) | Flash type | FGMOS transistor count | Date of introduction | Manufacturer(s) | Process | Area | Transistor density (tr./mm2) |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ? | 256 Kb | NOR | 262,144 | 1985 | Toshiba | 2,000 nm | ? | ? | [37] |

| 1 Mb | NOR | 1,048,576 | 1989 | Seeq, Intel | ? | ||||

| 4 Mb | NAND | 4,194,304 | 1989 | Toshiba | 1,000 nm | ||||

| 16 Mb | NOR | 16,777,216 | 1991 | Mitsubishi | 600 nm | ||||

| DD28F032SA | 32 Mb | NOR | 33,554,432 | 1993 | Intel | ? | 280 mm2 | 120,000 | [38][39] |

| ? | 64 Mb | NOR | 67,108,864 | 1994 | NEC | 400 nm | ? | ? | [37] |

| NAND | 67,108,864 | 1996 | Hitachi | ||||||

| 128 Mb | NAND | 134,217,728 | 1996 | Samsung, Hitachi | ? | ||||

| 256 Mb | NAND | 268,435,456 | 1999 | Hitachi, Toshiba | 250 nm | ||||

| 512 Mb | NAND | 536,870,912 | 2000 | Toshiba | ? | ? | ? | [40] | |

| 1 Gb | 2-bit NAND | 536,870,912 | 2001 | Samsung | ? | ? | ? | [37] | |

| Toshiba, SanDisk | 160 nm | ? | ? | [41] | |||||

| 2 Gb | NAND | 2,147,483,648 | 2002 | Samsung, Toshiba | ? | ? | ? | [42][43] | |

| 8 Gb | NAND | 8,589,934,592 | 2004 | Samsung | 60 nm | ? | ? | [42] | |

| 16 Gb | NAND | 17,179,869,184 | 2005 | Samsung | 50 nm | ? | ? | [44] | |

| 32 Gb | NAND | 34,359,738,368 | 2006 | Samsung | 40 nm | ||||

| THGAM | 128 Gb | Stacked NAND | 128,000,000,000 | April 2007 | Toshiba | 56 nm | 252 mm2 | 507,900,000 | [45] |

| THGBM | 256 Gb | Stacked NAND | 256,000,000,000 | 2008 | Toshiba | 43 nm | 353 mm2 | 725,200,000 | [46] |

| THGBM2 | 1 Tb | Stacked 4-bit NAND | 256,000,000,000 | 2010 | Toshiba | 32 nm | 374 mm2 | 684,500,000 | [47] |

| KLMCG8GE4A | 512 Gb | Stacked 2-bit NAND | 256,000,000,000 | 2011 | Samsung | ? | 192 mm2 | 1,333,000,000 | [48] |

| KLUFG8R1EM | 4 Tb | Stacked 3-bit V-NAND | 1,365,333,333,504 | 2017 | Samsung | ? | 150 mm2 | 9,102,000,000 | [49] |

| eUFS (1 TB) | 8 Tb | Stacked 4-bit V-NAND | 2,048,000,000,000 | 2019 | Samsung | ? | 150 mm2 | 13,650,000,000 | [50][51] |

| ? | 1 Tb | 232L TLC NAND die | 333,333,333,333 | 2022 | Micron | ? | 68.5 mm2 (memory array) |

4,870,000,000 (14.6 Gbit/mm2) |

[52][53][54][55] |

| ? | 16 Tb | 232L package | 5,333,333,333,333 | 2022 | Micron | ? | 68.5 mm2 (memory array) |

77,900,000,000 (16×14.6 Gbit/mm2) |

| Chip name | Capacity (bits) | ROM type | Transistor count | Date of introduction | Manufacturer(s) | Process | Area | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ? | ? | PROM | ? | 1956 | Arma | — | ? | [56][57] |

| 1 Kb | ROM (MOS) | 1,024 | 1965 | General Microelectronics | ? | ? | [58] | |

| 3301 | 1 Kb | ROM (bipolar) | 1,024 | 1969 | Intel | — | ? | [58] |

| 1702 | 2 Kb | EPROM (MOS) | 2,048 | 1971 | Intel | ? | 15 mm2 | [59] |

| ? | 4 Kb | ROM (MOS) | 4,096 | 1974 | AMD, General Instrument | ? | ? | [58] |

| 2708 | 8 Kb | EPROM (MOS) | 8,192 | 1975 | Intel | ? | ? | [38] |

| ? | 2 Kb | EEPROM (MOS) | 2,048 | 1976 | Toshiba | ? | ? | [60] |

| μCOM-43 ROM | 16 Kb | PROM (PMOS) | 16,000 | 1977 | NEC | ? | ? | [61] |

| 2716 | 16 Kb | EPROM (TTL) | 16,384 | 1977 | Intel | — | ? | [62][63] |

| EA8316F | 16 Kb | ROM (NMOS) | 16,384 | 1978 | Electronic Arrays | ? | 436 mm2 | [58][64] |

| 2732 | 32 Kb | EPROM | 32,768 | 1978 | Intel | ? | ? | [38] |

| 2364 | 64 Kb | ROM | 65,536 | 1978 | Intel | ? | ? | [65] |

| 2764 | 64 Kb | EPROM | 65,536 | 1981 | Intel | 3,500 nm | ? | [38][37] |

| 27128 | 128 Kb | EPROM | 131,072 | 1982 | Intel | ? | ||

| 27256 | 256 Kb | EPROM (HMOS) | 262,144 | 1983 | Intel | ? | ? | [38][66] |

| ? | 256 Kb | EPROM (CMOS) | 262,144 | 1983 | Fujitsu | ? | ? | [67] |

| 512 Kb | EPROM (NMOS) | 524,288 | 1984 | AMD | 1,700 nm | ? | [37] | |

| 27512 | 512 Kb | EPROM (HMOS) | 524,288 | 1984 | Intel | ? | ? | [38][68] |

| ? | 1 Mb | EPROM (CMOS) | 1,048,576 | 1984 | NEC | 1,200 nm | ? | [37] |

| 4 Mb | EPROM (CMOS) | 4,194,304 | 1987 | Toshiba | 800 nm | |||

| 16 Mb | EPROM (CMOS) | 16,777,216 | 1990 | NEC | 600 nm | |||

| MROM | 16,777,216 | 1995 | AKM, Hitachi | ? | ? | [69] |

Transistor computers

[編集]

Before transistors were invented, relays were used in commercial tabulating machines and experimental early computers. The world's first working programmable, fully automatic digital computer,[70] the 1941 Z3 22-bit word length computer, had 2,600 relays, and operated at a clock frequency of about 4–5 Hz. The 1940 Complex Number Computer had fewer than 500 relays,[71] but it was not fully programmable. The earliest practical computers used vacuum tubes and solid-state diode logic. ENIAC had 18,000 vacuum tubes, 7,200 crystal diodes, and 1,500 relays, with many of the vacuum tubes containing two triode elements.

The second generation of computers were transistor computers that featured boards filled with discrete transistors, solid-state diodes and magnetic memory cores. The experimental 1953 48-bit Transistor Computer, developed at the University of Manchester, is widely believed to be the first transistor computer to come into operation anywhere in the world (the prototype had 92 point-contact transistors and 550 diodes).[72] A later version the 1955 machine had a total of 250 junction transistors and 1,300 point-contact diodes. The Computer also used a small number of tubes in its clock generator, so it was not the first fully transistorized. The ETL Mark III, developed at the Electrotechnical Laboratory in 1956, may have been the first transistor-based electronic computer using the stored program method. It had about "130 point-contact transistors and about 1,800 germanium diodes were used for logic elements, and these were housed on 300 plug-in packages which could be slipped in and out."[73] The 1958 decimal architecture IBM 7070 was the first transistor computer to be fully programmable. It had about 30,000 alloy-junction germanium transistors and 22,000 germanium diodes, on approximately 14,000 Standard Modular System (SMS) cards. The 1959 MOBIDIC, short for "MOBIle DIgital Computer", at 12,000 pounds (6.0 short tons) mounted in the trailer of a semi-trailer truck, was a transistorized computer for battlefield data.

The third generation of computers used integrated circuits (ICs).[74] The 1962 15-bit Apollo Guidance Computer used "about 4,000 "Type-G" (3-input NOR gate) circuits" for about 12,000 transistors plus 32,000 resistors.[75]

The IBM System/360, introduced 1964, used discrete transistors in hybrid circuit packs.[74] The 1965 12-bit PDP-8 CPU had 1409 discrete transistors and over 10,000 diodes, on many cards. Later versions, starting with the 1968 PDP-8/I, used integrated circuits. The PDP-8 was later reimplemented as a microprocessor as the Intersil 6100, see below.[76]

The next generation of computers were the microcomputers, starting with the 1971 Intel 4004, which used MOS transistors. These were used in home computers or personal computers (PCs).

This list includes early transistorized computers (second generation) and IC-based computers (third generation) from the 1950s and 1960s.

| Computer | Transistor count | Year | Manufacturer | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transistor Computer | 92 | 1953 | University of Manchester | Point-contact transistors, 550 diodes. Lacked stored program capability. | [72] |

| TRADIC | 700 | 1954 | Bell Labs | Point-contact transistors | [72] |

| Transistor Computer (full size) | 250 | 1955 | University of Manchester | Discrete point-contact transistors, 1,300 diodes | [72] |

| IBM 608 | 3,000 | 1955 | IBM | Germanium transistors | [77] |

| ETL Mark III | 130 | 1956 | Electrotechnical Laboratory | Point-contact transistors, 1,800 diodes, stored program capability | [72][73] |

| Metrovick 950 | 200 | 1956 | Metropolitan-Vickers | Discrete junction transistors | |

| NEC NEAC-2201 | 600 | 1958 | NEC | Germanium transistors | [78] |

| Hitachi MARS-1 | 1,000 | 1958 | Hitachi | [79] | |

| IBM 7070 | 30,000 | 1958 | IBM | Alloy-junction germanium transistors, 22,000 diodes | |

| Matsushita MADIC-I | 400 | 1959 | Matsushita | Bipolar transistors | [80] |

| NEC NEAC-2203 | 2,579 | 1959 | NEC | [81] | |

| Toshiba TOSBAC-2100 | 5,000 | 1959 | Toshiba | [82] | |

| IBM 7090 | 50,000 | 1959 | IBM | Discrete germanium transistors | |

| PDP-1 | 2,700 | 1959 | Digital Equipment Corporation | Discrete transistors | |

| Olivetti Elea 9003 | ? | 1959 | Olivetti | 300,000 (?) discrete transistors and diodes | |

| Mitsubishi MELCOM 1101 | 3,500 | 1960 | Mitsubishi | Germanium transistors | [83] |

| M18 FADAC | 1,600 | 1960 | Autonetics | Discrete transistors | |

| CPU of IBM 7030 Stretch | 169,100 | 1961 | IBM | World's fastest computer from 1961 to 1964 | [84] |

| D-17B | 1,521 | 1962 | Autonetics | Discrete transistors | |

| NEC NEAC-L2 | 16,000 | 1964 | NEC | Ge transistors | [85] |

| CDC 6600 (entire computer) | 400,000 | 1964 | Control Data Corporation | World's fastest computer from 1964 to 1969 | [86] |

| IBM System/360 | ? | 1964 | IBM | Hybrid circuits | |

| PDP-8 "Straight-8" | 1,409[76] | 1965 | Digital Equipment Corporation | discrete transistors, 10,000 diodes | |

| PDP-8/S | 1,001 | 1966 | Digital Equipment Corporation | discrete transistors, diodes | |

| PDP-8/I | 1,409[要出典] | 1968 | Digital Equipment Corporation | 74 series TTL circuits | |

| Apollo Guidance Computer Block I | 12,300 | 1966 | Raytheon / MIT Instrumentation Laboratory | 4,100 ICs, each containing a 3-transistor, 3-input NOR gate. (Block II had 2,800 dual 3-input NOR gates ICs.) |

Logic functions

[編集]Transistor count for generic logic functions is based on static CMOS implementation.

| Function | Transistor count | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| NOT | 2 | |

| Buffer | 4 | |

| NAND 2-input | 4 | |

| NOR 2-input | 4 | |

| AND 2-input | 6 | |

| OR 2-input | 6 | |

| NAND 3-input | 6 | |

| NOR 3-input | 6 | |

| XOR 2-input | 6 | |

| XNOR 2-input | 8 | |

| MUX 2-input with TG | 6 | |

| MUX 4-input with TG | 18 | |

| NOT MUX 2-input | 8 | |

| MUX 4-input | 24 | |

| 1-bit full adder | 24 | |

| 1-bit adder–subtractor | 48 | |

| AND-OR-INVERT | 6 | [87] |

| Latch, D gated | 8 | |

| Flip-flop, edge triggered dynamic D with reset | 12 | |

| 8-bit multiplier | 3,000 | |

| 16-bit multiplier | 9,000 | |

| 32-bit multiplier | 21,000 | [要出典] |

| small-scale integration | 2–100 | [88] |

| medium-scale integration | 100–500 | [88] |

| large-scale integration | 500–20,000 | [88] |

| very-large-scale integration | 20,000–1,000,000 | [88] |

| ultra-large scale integration | >1,000,000 |

Parallel systems

[編集]Historically, each processing element in earlier parallel systems—like all CPUs of that time—was a serial computer built out of multiple chips. As transistor counts per chip increases, each processing element could be built out of fewer chips, and then later each multi-core processor chip could contain more processing elements.[89]

Goodyear MPP: (1983?) 8 pixel processors per chip, 3,000 to 8,000 transistors per chip.[89]

Brunel University Scape (single-chip array-processing element): (1983) 256 pixel processors per chip, 120,000 to 140,000 transistors per chip.[89]

Cell Broadband Engine: (2006) with 9 cores per chip, had 234 million transistors per chip.[90]

Other devices

[編集]| Device type | Device name | Transistor count | Date of introduction | Designer(s) | Manufacturer(s) | MOS process | Area | Transistor density, tr./mm2 | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep learning engine / IPU[注釈 3] | Colossus GC2 | 23,600,000,000 | 2018 | Graphcore | TSMC | 16 nm | ~800 mm2 | 29,500,000 | [91][92][93] |

| Deep learning engine / IPU | Wafer Scale Engine | 1,200,000,000,000 | 2019 | Cerebras | TSMC | 16 nm | 46,225 mm2 | 25,960,000 | [94][2][3][4] |

| Deep learning engine / IPU | Wafer Scale Engine 2 | 2,600,000,000,000 | 2020 | Cerebras | TSMC | 7 nm | 46,225 mm2 | 56,250,000 | [5][95][96] |

| Network switch | NVLink4 NVSwitch | 25,100,000,000 | 2022 | Nvidia | TSMC | N4 (4 nm) | 294 mm2 | 85,370,000 | [97] |

Transistor density

[編集]The transistor density is the number of transistors that are fabricated per unit area, typically measured in terms of the number of transistors per square millimeter (mm2). The transistor density usually correlates with the gate length of a semiconductor node (also known as a semiconductor manufacturing process), typically measured in nanometers (nm). 2019年現在[update], the semiconductor node with the highest transistor density is TSMC's 5 nanometer node, with 171.3 million transistors per square millimeter (note this corresponds to a transistor-transistor spacing of 76.4 nm, far greater than the relative meaningless "5nm")[98]

MOSFET nodes

[編集]See also

[編集]- Gate count, an alternate metric

- Dennard scaling

- Electronics industry

- Integrated circuit

- List of best-selling electronic devices

- List of semiconductor scale examples

- MOSFET

- Semiconductor

- Semiconductor device

- Semiconductor device fabrication

- Semiconductor industry

- Transistor

- Cerebras Systems

Notes

[編集]References

[編集]- ^ Khosla, Robin (2017). Alternate high-k dielectrics for next-generation CMOS logic and memory technology (Thesis). IIT Mandi.

- ^ a b Feldman (August 2019). “Machine Learning chip breaks new ground with waferscale integration”. nextplatform.com. 2019年9月6日閲覧。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "NextPlatform-WSE"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ a b Cutress (August 2019). “Hot Chips 31 Live Blogs: Cerebras' 1.2 Trillion Transistor Deep Learning Processor”. anandtech.com. 2019年9月6日閲覧。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "AnandTech-WSE"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ a b “A Look at Cerebras Wafer-Scale Engine: Half Square Foot Silicon Chip” (英語). WikiChip Fuse (2019年11月16日). 2019年12月2日閲覧。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "WikichipFuse-WSE"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ a b Everett (August 26, 2020). “World's largest CPU has 850,000 7 nm cores that are optimized for AI and 2.6 trillion transistors”. TechReportArticles. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name ":1"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ "Apple introduces M2 Ultra" (Press release). Apple. 5 June 2023.

- ^ “John Gustafson's answer to How many individual transistors are in the world's most powerful supercomputer?”. Quora. 2019年8月22日閲覧。

- ^ Laws (2018年4月2日). “13 Sextillion & Counting: The Long & Winding Road to the Most Frequently Manufactured Human Artifact in History”. Computer History Museum. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Handy (2014年5月26日). “How Many Transistors Have Ever Shipped?”. Forbes. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “1971: Microprocessor Integrates CPU Function onto a Single Chip”. The Silicon Engine. Computer History Museum. 4 September 2019閲覧。

- ^ Holt. “World's First Microprocessor”. 5 March 2016閲覧。 “1st fully integrated chip set microprocessor”

- ^ “Alpha 21364 - Microarchitectures - Compaq - WikiChip”. en.wikichip.org. 2019年9月8日閲覧。

- ^ Williams. “Nvidia's Tesla P100 has 15 billion transistors, 21TFLOPS”. www.theregister.co.uk. 2019年8月12日閲覧。

- ^ "“Altera's new 40nm FPGAs — 2.5 billion transistors!”. pldesignline.com. June 19, 2010時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。January 22, 2009閲覧。

- ^ “Altera unveils 28-nm Stratix V FPGA family” (April 20, 2010). April 20, 2010閲覧。

- ^ “Design of a High-Density SoC FPGA at 20nm” (2014年). April 23, 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 16, 2017閲覧。

- ^ Maxfield, Clive (October 2011). "New Xilinx Virtex-7 2000T FPGA provides equivalent of 20 million ASIC gates". EETimes. AspenCore. 2019年9月4日閲覧。

- ^ Greenhill, D.; Ho, R.; Lewis, D.; Schmit, H.; Chan, K. H.; Tong, A.; Atsatt, S.; How, D. et al. (February 2017). “3.3 a 14nm 1GHz FPGA with 2.5D transceiver integration”. 2017 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC). pp. 54–55. doi:10.1109/ISSCC.2017.7870257. ISBN 978-1-5090-3758-2

- ^ “3.3 A 14nm 1GHz FPGA with 2.5D transceiver integration | DeepDyve” (2017年5月17日). May 17, 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ Santarini, Mike (May 2014). "Xilinx Ships Industry's First 20-nm All Programmable Devices" (PDF). Xcell journal. No. 86. Xilinx. p. 14. 2014年6月3日閲覧。

- ^ Gianelli (January 2015). “Xilinx Delivers the Industry's First 4M Logic Cell Device, Offering >50M Equivalent ASIC Gates and 4X More Capacity than Competitive Alternatives”. www.xilinx.com. 2019年8月22日閲覧。

- ^ Sims (August 2019). “Xilinx Announces the World's Largest FPGA Featuring 9 Million System Logic Cells”. www.xilinx.com. 2019年8月22日閲覧。

- ^ Verheyde (August 2019). “Xilinx Introduces World's Largest FPGA With 35 Billion Transistors”. www.tomshardware.com. 2019年8月23日閲覧。

- ^ Cutress (August 2019). “Xilinx Announces World Largest FPGA: Virtex Ultrascale+ VU19P with 9m Cells”. www.anandtech.com. 2019年9月25日閲覧。

- ^ Abazovic, Fuad (May 2019). “Xilinx 7nm Versal taped out last year” 2019年9月30日閲覧。

- ^ Cutress, Ian (August 2019). “Hot Chips 31 Live Blogs: Xilinx Versal AI Engine” 2019年9月30日閲覧。

- ^ Krewell, Kevin (August 2019). “Hot Chips 2019 highlights new AI strategies” 2019年9月30日閲覧。

- ^ Leibson, Steven (2019年11月6日). “Intel announces Intel Stratix 10 GX 10M FPGA, worlds highest capacity with 10.2 million logic elements” 2019年11月7日閲覧。

- ^ Verheyde, Arne (2019年11月6日). “Intel Introduces World's Largest FPGA With 43.3 Billion Transistors” 2019年11月7日閲覧。

- ^ Cutress, Ian (August 2020). “Hot Chips 2020 Live Blog: Xilinx Versal ACAPs” 2020年9月9日閲覧。

- ^ “Xilinx Announces Full Production Shipments of 7nm Versal AI Core and Versal Prime Series Devices”. (April 27, 2021) 2021年5月8日閲覧。

- ^ “Late 1960s: Beginnings of MOS memory”. Semiconductor History Museum of Japan (2019年1月23日). 27 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “1970: Semiconductors compete with magnetic cores”. Computer History Museum. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “2.1.1 Flash Memory”. TU Wien. 20 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ Shilov. “SK Hynix Starts Production of 128-Layer 4D NAND, 176-Layer Being Developed”. www.anandtech.com. 2019年9月16日閲覧。

- ^ “Samsung Begins Production of 100+ Layer Sixth-Generation V-NAND Flash”. PC Perspective (2019年8月11日). 2019年9月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f “Memory”. STOL (Semiconductor Technology Online). November 2, 2023時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。25 June 2019閲覧。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "stol"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ a b c d e f “A chronological list of Intel products. The products are sorted by date.”. Intel museum. Intel Corporation (July 2005). August 9, 2007時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。July 31, 2007閲覧。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "Intel-Product-Timeline"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ “DD28F032SA Datasheet”. Intel. 27 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “TOSHIBA ANNOUNCES 0.13 MICRON 1Gb MONOLITHIC NAND FEATURING LARGE BLOCK SIZE FOR IMPROVED WRITE/ERASE SPEED PERFORMANCE”. Toshiba. (September 9, 2002). オリジナルのMarch 11, 2006時点におけるアーカイブ。 11 March 2006閲覧。

- ^ “TOSHIBA AND SANDISK INTRODUCE A ONE GIGABIT NAND FLASH MEMORY CHIP, DOUBLING CAPACITY OF FUTURE FLASH PRODUCTS”. Toshiba. (12 November 2001) 20 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ a b “Our Proud Heritage from 2000 to 2009”. Samsung Semiconductor. Samsung. 25 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “TOSHIBA ANNOUNCES 1 GIGABYTE COMPACTFLASH CARD”. Toshiba. (September 9, 2002). オリジナルのMarch 11, 2006時点におけるアーカイブ。 11 March 2006閲覧。

- ^ “History”. Samsung Electronics. Samsung. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “TOSHIBA COMMERCIALIZES INDUSTRY'S HIGHEST CAPACITY EMBEDDED NAND FLASH MEMORY FOR MOBILE CONSUMER PRODUCTS”. Toshiba. (April 17, 2007). オリジナルのNovember 23, 2010時点におけるアーカイブ。 23 November 2010閲覧。

- ^ “Toshiba Launches the Largest Density Embedded NAND Flash Memory Devices”. Toshiba. (7 August 2008) 21 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “Toshiba Launches Industry's Largest Embedded NAND Flash Memory Modules”. Toshiba. (17 June 2010) 21 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “Samsung e·MMC Product family”. Samsung Electronics (December 2011). November 8, 2019時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。15 July 2019閲覧。

- ^ Shilov, Anton (December 5, 2017). “Samsung Starts Production of 512 GB UFS NAND Flash Memory: 64-Layer V-NAND, 860 MB/s Reads”. AnandTech 23 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ Manners, David (30 January 2019). “Samsung makes 1TB flash eUFS module”. Electronics Weekly 23 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ Tallis, Billy (October 17, 2018). “Samsung Shares SSD Roadmap for QLC NAND And 96-layer 3D NAND”. AnandTech 27 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “Micron's 232 Layer NAND Now Shipping”. AnandTech (2022年7月26日). Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “232-Layer NAND”. Micron. 2022年10月17日閲覧。

- ^ “First to Market, Second to None: the World's First 232-Layer NAND”. Micron (2022年7月26日). Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “Comparison: Latest 3D NAND Products from YMTC, Samsung, SK hynix and Micron”. TechInsights (2023年1月11日). Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Han-Way Huang (5 December 2008). Embedded System Design with C805. Cengage Learning. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-111-81079-5. オリジナルの27 April 2018時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Marie-Aude Aufaure; Esteban Zimányi (17 January 2013). Business Intelligence: Second European Summer School, eBISS 2012, Brussels, Belgium, July 15-21, 2012, Tutorial Lectures. Springer. p. 136. ISBN 978-3-642-36318-4. オリジナルの27 April 2018時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b c d “1965: Semiconductor Read-Only-Memory Chips Appear”. Computer History Museum. 20 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “1971: Reusable semiconductor ROM introduced”. The Storage Engine. Computer History Museum. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ Iizuka, H.; Masuoka, F.; Sato, Tai; Ishikawa, M. (1976). “Electrically alterable avalanche-injection-type MOS READ-ONLY memory with stacked-gate structure”. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 23 (4): 379–387. Bibcode: 1976ITED...23..379I. doi:10.1109/T-ED.1976.18415. ISSN 0018-9383.

- ^ μCOM-43 SINGLE CHIP MICROCOMPUTER: USERS' MANUAL. NEC Microcomputers. (January 1978) 27 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “Intel: 35 Years of Innovation (1968–2003)”. Intel (2003年). 4 November 2021時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。26 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “2716: 16K (2K x 8) UV ERASABLE PROM”. Intel. September 13, 2020時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。27 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “1982 CATALOG”. NEC Electronics. 20 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ Component Data Catalog. Intel. (1978). pp. 1–3 27 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “27256 Datasheet”. Intel. 2 July 2019閲覧。

- ^ “History of Fujitsu's Semiconductor Business”. Fujitsu. 2 July 2019閲覧。

- ^ “D27512-30 Datasheet”. Intel. 2 July 2019閲覧。

- ^ “Japanese Company Profiles”. Smithsonian Institution (1996年). 27 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “A Computer Pioneer Rediscovered, 50 Years On”. The New York Times. (April 20, 1994). オリジナルのNovember 4, 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “History of Computers and Computing, Birth of the modern computer, Relays computer, George Stibitz”. history-computer.com. 2019年8月22日閲覧。 “Initially the 'Complex Number Computer' performed only complex multiplication and division, but later a simple modification enabled it to add and subtract as well. It used about 400-450 binary relays, 6-8 panels, and ten multiposition, multipole relays called "crossbars" for temporary storage of numbers.”

- ^ a b c d e “1953: Transistorized Computers Emerge”. Computer History Museum. 19 June 2019閲覧。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "computerhistory"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ a b “ETL Mark III Transistor-Based Computer”. IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan. 19 June 2019閲覧。 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "etl3"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ a b “Brief History”. IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “1962: Aerospace systems are first the applications for ICs in computers | The Silicon Engine | Computer History Museum”. www.computerhistory.org. 2019年9月2日閲覧。

- ^ a b “PDP-8 (Straight 8) Computer Functional Restoration”. www.pdp8.net. 2019年8月22日閲覧。 “backplanes contain 230 cards, approximately 10,148 diodes, 1409 transistors, 5615 resistors, and 1674 capacitors” 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "straight 8"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ “IBM 608 calculator”. IBM (January 23, 2003). 8 March 2021閲覧。

- ^ “【NEC】 NEAC-2201”. IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “【Hitachi and Japanese National Railways】 MARS-1”. IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “【Matsushita Electric Industrial】 MADIC-I transistor-based computer”. IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “【NEC】 NEAC-2203”. IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “【Toshiba】 TOSBAC-2100”. IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ “【Mitsubishi Electric】 MELCOM 1101”. IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ Erich Bloch (1959). The Engineering Design of the Stretch Computer (PDF). Eastern Joint Computer Conference.

- ^ “【NEC】NEAC-L2”. IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan. 19 June 2019閲覧。

- ^ Thornton, James (1970). Design of a Computer: the Control Data 6600. p. 20

- ^ Richard F. Tinder (January 2000). Engineering Digital Design. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-691295-1

- ^ a b c d Engineers, Institute of Electrical Electronics (2000). 100-2000 (7th ed.). doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2000.322230. ISBN 978-0-7381-2601-2. IEEE Std 100-2000

- ^ a b c

Smith, Kevin (August 11, 1983). “Image processor handles 256 pixels simultaneously”. Electronics.Smith, Kevin (August 11, 1983). "Image processor handles 256 pixels simultaneously". Electronics.

引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグ; name "kevin"が異なる内容で複数回定義されています - ^ Kanellos, Michael (February 9, 2005). “Cell chip: Hit or hype?”. CNET News. オリジナルの2012年10月25日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Kennedy (June 2019). “Hands-on With a Graphcore C2 IPU PCIe Card at Dell Tech World”. servethehome.com. 2019年12月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Colossus – Graphcore”. en.wikichip.org. 2019年12月29日閲覧。

- ^ Graphcore. “IPU Technology”. www.graphcore.ai. Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Hruska (August 2019). “Cerebras Systems Unveils 1.2 Trillion Transistor Wafer-Scale Processor for AI”. extremetech.com. 2019年9月6日閲覧。

- ^ “Cerebras Unveils 2nd Gen Wafer Scale Engine: 850,000 Cores, 2.6 Trillion Transistors - ExtremeTech”. www.extremetech.com. 2021年4月22日閲覧。

- ^ “Cerebras Wafer Scale Engine WSE-2 and CS-2 at Hot Chips 34”. ServeTheHome (2022年8月23日). Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ “NVIDIA NVLink4 NVSwitch at Hot Chips 34”. ServeTheHome (2022年8月22日). Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 accessdate は必須です。

- ^ Schor (2019年4月6日). “TSMC Starts 5-Nanometer Risk Production”. WikiChip Fuse. 2019年4月7日閲覧。

External links

[編集][[Category:トランジスタ]] [[Category:集積回路]] [[Category:未査読の翻訳があるページ]]