利用者:GeeKay/sandbox3

|

ここはGeeKayさんの利用者サンドボックスです。編集を試したり下書きを置いておいたりするための場所であり、百科事典の記事ではありません。ただし、公開の場ですので、許諾されていない文章の転載はご遠慮ください。

登録利用者は自分用の利用者サンドボックスを作成できます(サンドボックスを作成する、解説)。 その他のサンドボックス: 共用サンドボックス | モジュールサンドボックス 記事がある程度できあがったら、編集方針を確認して、新規ページを作成しましょう。 |

| 金星 Venus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| 仮符号・別名 | 明星 明けの明星・宵の明星[1][2] 太白 | ||||||

| 見かけの等級 (mv) | -4.7[1] -4.9(最大光度)[3][4] | ||||||

| 分類 | 地球型惑星 | ||||||

| 軌道の種類 | 太陽周回軌道 | ||||||

| 発見 | |||||||

| 発見日 | 不明 | ||||||

| 発見者 | 不明 | ||||||

| 発見方法 | 目視 | ||||||

| 出典についての注釈 | |||||||

| 出典 | 以下、特記しない限り [5][6]を出典とする。 | ||||||

| 軌道要素と性質 元期:J2000.0 | |||||||

| 太陽からの平均距離 | 0.72333199 au | ||||||

| 平均公転半径 | 108,208,930 km | ||||||

| 近日点距離 (q) | 0.7184336 au[注 1] | ||||||

| 遠日点距離 (Q) | 0.7282304 au[注 2] | ||||||

| 離心率 (e) | 0.006772[7] | ||||||

| 公転周期 (P) | 224.701 日 | ||||||

| 会合周期 | 583.92日 | ||||||

| 平均軌道速度 | 35.02 km/s | ||||||

| 最大軌道速度 | 35.26 km/s | ||||||

| 最小軌道速度 | 34.79 km/s | ||||||

| 軌道傾斜角 (i) | 3.39471° | ||||||

| 近日点引数 (ω) | 54.884° | ||||||

| 昇交点黄経 (Ω) | 76.68°[7] | ||||||

| 平均近点角 (M) | 50.115° | ||||||

| 太陽の惑星 | |||||||

| 衛星の数 | 0 | ||||||

| 物理的性質 | |||||||

| 赤道面での直径 | 12,103.6 km | ||||||

| 半径 | 6051.8 ± 1.0 km[8] | ||||||

| 表面積 | 4.60 ×108 km2 | ||||||

| 体積 | 92.843 ×1010 km3 | ||||||

| 質量 | 4.8675 ×1024 kg[9] | ||||||

| 地球との相対質量 | 0.815 | ||||||

| 地球との相対半径 | 0.949 | ||||||

| 平均密度 | 5.243 g/cm3 | ||||||

| 表面重力 | 8.87 m/s2 | ||||||

| 脱出速度 | 10.36 km/s[10] | ||||||

| 自転速度 | 6.52 km/h (1.81 m/s) | ||||||

| 自転周期 | -243.025 日 (逆行) | ||||||

| 赤道傾斜角 | 177.36° (軌道面に対する角度) | ||||||

| 表面温度 |

| ||||||

| 大気の性質 | |||||||

| 大気圧 | 92 bar (9.2 MPa) | ||||||

| 二酸化炭素 | 96.5% | ||||||

| 窒素 | 3.5% | ||||||

| 二酸化硫黄 | 0.015% | ||||||

| 水蒸気 | 0.002% | ||||||

| 一酸化炭素 | 0.0017% | ||||||

| アルゴン | 0.007% | ||||||

| ヘリウム | 0.0012% | ||||||

| ネオン | 0.0007% | ||||||

| 硫化カルボニル | わずか | ||||||

| 塩化水素 | わずか | ||||||

| フッ化水素 | わずか | ||||||

| ■Template (■ノート ■解説) ■Project | |||||||

金星(きんせい、英語: Venus)は太陽系で太陽から2番目に近い軌道を224.7日周期で公転している惑星である[11]。太陽系の中で最も長い自転周期(243日)を持ち、また他の惑星とは逆に時計回りで自転している。自然に作られた衛星は持たない。金星の英語名Venusは愛と美の女神ウェヌスに由来する。金星は地球では太陽、月に次いで明るい天体で、最大で-4.7等級に達する。条件が良ければ金星の光だけで影が生じることもある[12][13]。これほど明るい理由は金星が内惑星で地球からの距離が近いからで、離角が最大で47.8度もあるからである。

金星は地球型惑星であり、大きさや質量が似通っているので、地球の姉妹惑星や地球の双子惑星と表現されることがある。しかし、環境は地球とは大きく異なる。大気の成分のうち、96%は二酸化炭素であり、大気圧は地球の92倍である。さらに、表面温度は平均で735K(462 ℃)にもなり、太陽に最も近い水星よりも高温である。金星は反射率が高い硫酸の雲で覆われているため、外部から可視光で表面を観測することはできない。過去には海が存在していた可能性があるが、暴走温室効果が起こり、表面温度が上昇した末に海が全て蒸発してしまったと考えられている[14][15][16]。また、金星は磁場を持っていないため、現在は太陽風によって乾燥した砂漠のような風景が広がっており[17]、周期的に火山活動が発生しているとされている。

夜空で明るい天体の一つとして、金星は人類の文化における重要な定着物となってきた。特に「宵の明星」と「開けの明星」は作家や詩人のための主要なインスピレーションとなっている。金星は空を横切る惑星として紀元前2000年にはすでに知られていた[18]。また、地球に最も接近する惑星であったため、初期の宇宙探査の重要なターゲットとされた。初めて探査に成功したのは史上初めて、地球以外の惑星にたどり着いたマリナー2号(1962年)である。そして、最初に表面への着陸に成功したのはベネラ7号である。初めて詳細な表面の地図が1991年、マゼランによって作成されるまでは探査車による調査は困難であった。

物理的特徴[編集]

金星は太陽系に4つある、地球のように岩石で構成された地球型惑星の1つである。先述の通り、質量や大きさが地球に似ているため、地球の姉妹惑星や双子惑星と表現されることがある[19]。金星の直径は12,103kmで、これは地球より約650km小さい。質量は地球の81.5%であり、表面の大気成分は地球とは大きく異なる。大気の96.5%が二酸化炭素で残りの3.5%は窒素である[20]。

地形[編集]

金星の表面が明らかになるまで、金星表面の探査は宇宙探査の重要な対象であった。1975年と1982年に行われたベネラ計画による着陸機が初めて、金星表面が土砂や岩が散乱していることを明らかにした[21]。1990年から91年にかけて観測を行った探査機マゼランは表面の全球地図を完成させた。この地図にはかつての火山活動の痕跡や現在も火山活動が続いている証拠を発見した[22][23]。

金星表面の約80%は火山活動によって流出された溶岩によって作られた比較的、なめらかな平原である[24]。残りの20%は比較的、高地が多い大陸が占めている。大陸は北半球と南半球それぞれに1つずつ存在している。北半球にある大陸は、愛の女神イシュタルに因んで、イシュタル大陸と名付けられている。オーストラリア大陸ほどの大きさがある。金星で最も標高が高いマクスウェル山はイシュタル大陸にあり、高さは金星表面の平均標高よりはるかに高い、約11kmに及ぶ。南半球に存在する大陸はアフロディーテ大陸と名付けられている。南アメリカ大陸ほどの大きさで、2つの大陸では大きい方である。

他の地球型惑星と同様に、金星にもいくつかクレーターが発見されているが、年齢が3億年歳から6億年歳である、若いものがほとんどである[25][26]。表面にはクレーター以外にも山々や谷などがあり、比較的、個性ある地形が広がっている。金星には上記の大地形のほかに、コロナ(Coronae)と呼ばれる円形に盛り上がった地域や、中心から放射状に盛り上がりを見せるノバ(Novae)、パンケーキ状に丸くひろがった台地や、断層や褶曲が入り組むテセラなどの特徴的な小地形が数多く存在する。このうちコロナやノバ、パンケーキ状の地形は火山活動によって形成されたと考えられている[27][28][29]。

金星表面の地形の名前のほとんどは神話に登場する女性の名前に由来している[30]。しかし、例外としてマクスウェル山が挙げられる。マクスウェル山は物理学者ジェームズ・クラーク・マクスウェルに由来する。また、アルファレジオ、ベータレジオ、Ovda Regioも例外である。これらの地形は国際天文学連合が金星の地形の命名法を定める前に名称が決定されたために例外となっている[31]。

表面の地形[編集]

金星表面の大部分は火山活動によって形成されたと考えられている。金星のほとんどの火山は地球の数倍の規模があり、全長100kmを越える巨大な火山が167個も存在している。地球上でこの規模の火山はハワイ島しかない[29]。金星は地球よりも火山活動が活発とされているため、火山活動が起きた年代よりも古い地殻は残されていない。

ソビエト連邦が打ち上げたベネラ9号の分光観測によって、金星の大気中で雷が生じている間接的な証拠を発見し[32]、その後のベネラ12号の降下プローブが雷によるものと思われる雷鳴を観測した[33][34]。2007年、欧州宇宙機関(ESA)が打ち上げたビーナス・エクスプレスがホイスラー波を使用した観測によって、金星の大気中で雷が発生していることが確認された[35][36]。また、金星の高度25kmの地点で硫酸の雨が降り注いでいることも確認されている。この雷雨の原因として、現在も続いている火山活動によって巻き上げられた火山灰による可能性がある。その証拠として1978年から1986年の間に大気中の二酸化硫黄の割合が10倍減少し、2006年に再び、割合が急上昇しているという研究結果がある[37]。しかし、その後、二酸化硫黄の割合は再び10倍ほど減少した。これは周期的に大規模な火山活動が発生したことを意味している[38][39]。

2008年と2009年には、ビーナス・エクスプレスは火山活動の直接的な証拠としてマアト山の近くにあるガニス峡谷に局地的に赤外線が強い領域が4つ、ほぼ一直線上に存在していることを発見した[40]。3つ以上、赤外線が強い領域が並んでいることは、そこに火山活動によって流出した溶岩が存在している可能性を示している[41][42] 。赤外線が強い領域の温度は計測できなかったが、おそらく800Kから1100Kの間だと推測されており、これは金星の平均表面温度の740Kよりも高温である[43]。

金星のほとんどのクレーターは全球に渡ってほぼ均等に分布している。地球や月と同じく、金星のクレーターも形状や分布を調べれば、クレーターの劣化や浸食などの状況を推測することが出来る。地球上では雨や風などにより、風化や浸食の影響を受け、形成時とは原形をとどめていない形状のクレーターが多いが、金星では約85%のクレーターが形成時と同じ形状で残されている。これは浸食などの影響をあまり受けていない、すなわち比較的新しいクレーターが多いあることを表している。これは3億年前から6億年前の間に、金星で全球規模の火山活動が発生し、それによって流出した溶岩により、その時にすでに形成されていたクレーターが埋め尽くされて消滅したからだと考えられている[25][26]。地球では地殻変動が常に発生しているが、金星では地殻変動が発生しても、一時的にしか続かないと考えられている。

金星のクレーターは直径3kmから280kmとかなり差がある。しかし、大気が非常に濃いため、直径3km以下の小さなクレーターを外から発見するのは極めて困難である[44]。しかし、直径50m以内の天体の場合、表面に衝突するまでの間に大気圏で燃え尽きてしまうため、小さなクレーターは形成されにくいと考えられている[45]。

内部構造[編集]

金星では内部構造を推定するのに重要な地震などの現象が確認されていないが、それでも内部構造は慣性モーメントなどから概ね推測できる[46]。金星と地球は大きさや密度が似通っているので、内部も地球と同じく、核とマントルと地殻から構成されている。また、金星の内部が冷却されるペースも地球とほぼ同じだと考えられているため、少なくとも核の部分は液体になっていると考えられている[47]。しかし、金星よりわずかに小さいため、中心部にかかる圧力は地球より24%小さい[48]。内部構造において、地球との大きな違いはプレートテクトニクスが存在していないことである[25]。しかし、近年までなぜ金星にプレートテクトニクスがないのかは不明であったが、最近になって地殻とマントルの岩石の粘度に違いがあることが分かってきた[49]。この粘度の違いから数値解析を行った結果、マントル内の対流が地殻まで到達しないことが判明した[49]。地球では地殻とマントルに粘度の違いがほぼないため、マントルの対流に伴い、地殻も対流するプレートテクトニクスが発生するが、金星では地殻が表面に残り続けるために地殻変動が起きないと考えられる。

大気と気候[編集]

金星の大気成分の96.5%は二酸化炭素で、残りの3.5%のほとんどが窒素であり、その他に二酸化硫黄なども含まれている[50]。大気圧は地球の92倍にもなり、これは地球上の海における水深900mの水圧に匹敵する。表面の二酸化炭素の密度は65kg/m3で、表面温度が20℃と仮定した場合の地球上の水の50倍である。この大量の二酸化炭素による暴走温室効果で、表面が平均735K(462℃)という、太陽系内でも特に高温な温度まで加熱されていると考えられている[11][51]。これは太陽に最も近い水星(平均442K、169℃[52])よりも高温である[53]。金星は水星と比べ太陽からの距離が倍、太陽光の照射は75% (2,660 W/m2) である。金星の自転は非常にゆっくりなもの(自転と公転の回転の向きが逆なので金星の1日はおよそ地球の117日)であるが、熱による対流と大気の慣性運動のため、昼でも夜でも地表の温度にそれほどの差はない。これらのことから、伝統的に金星の表面の様子は「地獄」と表現されることがある[54][55]。

金星の表面組成から見ると、人間が人工の居住空間を建設したとしても、金星で地球と同様の生活を営むのは極めて過酷である。しかし、気温が30℃から80℃ほどとされている高度50kmの上層での居住が検討されているが、周辺の雲や物質が酸性であることから、人工物の長時間保存には適さないという主張もある[56][57][58]。

大気には上記の二酸化炭素以外にも、硫酸や硫黄エアロゾル、塩化鉄(III)、わずかな水が含まれている[59][60]。雲には硫酸鉄 (III)や塩化アルミニウムが含まれていることが確認されている。この雲が太陽光の約90%を反射、散乱させて金星表面の直接観測を妨げている。その為、金星は地球よりも太陽に近いが、表面に届く太陽光の大きさは地球の方が大きい。金星の上層部ではわずか4日から5日で金星を一周する極めて強い風が吹いており、その速度は秒速85m/s(時速300km/h)で金星の自転速度の60倍にもなる[61]。この風は自転速度を越えて吹く風という意味でスーパーローテーション(Super Rotation)と言われる。自転速度の60倍の速度を持つスーパーローテーションに対して、地球上で最も強い風でも自転速度の10%から20%にしかならない[62]。この現象は多くの人々の興味を引くこととなり様々な理論が提示されてきたが、未だに解明には至っておらず、金星最大の謎の1つとされている。

金星の表面温度は、昼夜や赤道、極地を問わず、ほぼ等温である[63]。これは、金星の赤道傾斜角が地球の23.4度に対してわずか3度[注 4]ほどしかなく、季節変化がほとんどないためである[64]。しかし、高度が高い雲の上層部のみ、温度に大きな差が見られる。金星で最も標高が高いマクスウェル山は気圧が4.5 Mpa(45 bar)と、表面のほぼ半分であり、マクスウェル山の頂上付近の温度は約655K(約382℃)になっており、これは金星の表面では最も温度が低い領域である[65][66]。1995年、探査機マゼランはマクスウェル山の頂上に電波による反射波が高い領域が存在していることを発見した。この性質は地球上の雪と似ているが、金星上で最も表面温度が低いとはいえ、380℃という高温の中では当然、水から生成された雪は存在しない。2016年現在、この現象の原因についての有力な仮説は存在しない。仮にこの反射波が高い領域に雪のような物質があれば、高温ではあるが、地球の雪と同様のプロセスで形成される可能性もある。この現象は金星の雪(Venus snow)という表現で呼ばれている。

先述のとおり、金星の雲でも地球の雲と同様に雷が発生する[35]。雷は最初、ソビエト連邦の探査で検出され、その後のベネラ計画では雷の存在が議論された。2006年から2007年にかけてビーナス・エクスプレスははっきりとしたホイッスラーモード波が観測された。この観測から、金星で発生する雷の数は地球の半分である事が判明した[35]。2007年には同じくビーナス・エクスプレスが南極に巨大な大気の渦が存在している事を発見した[67][68]。ビーナス・エクスプレスは南極の渦の観測を続け、2011年までにその詳細な構造を明らかにした[69]。

2011年、欧州宇宙機関のビーナス・エクスプレスが大気の上層にオゾン層が存在する事を発見した[70][71]。

2012年、ビーナス・エクスプレスの5年分のデータを解析した結果、上空125kmのところに、気温が-175℃の極低温の場所があることがわかった。この低温層は、2つの高温の層に挟まっており、夜の大気が優勢な部分が低温になっていると考えられている。この極低温から、二酸化炭素の氷が生じているとも考えられている[72]。

2013年1月29日、ESAのビーナス・エクスプレスが金星から放出される電離層があたかも彗星のように太陽と反対側に膨らんでいる様子を観測した[73][74][75]。これは、地球のようなはっきりとした磁場を持たない金星に太陽風がどう影響を及ぼすかの研究を進める上での大きな発見となった。

磁場とコア[編集]

1967年、ベネラ4号は地球よりはるかに微弱な磁場がある事を発見した。この磁場は地球のように核内でのダイナモ理論によって生じているものではなく、電離層と太陽風との相互作用によって生じている[78][79]。金星の小さな磁気圏は宇宙から飛来する宇宙放射線をほとんど遮断する事が出来ない。この放射線はcloud-to-cloud lignting dischargesと呼ばれる放電現象を起こす事がある[80]。

物理的特徴が地球に近いにも関わらず、磁場の強度がこれほど異なるのは、驚くべきことであった。

核からの磁場が無い原因として、金星は核が冷却されておらず、固体の内核を持っていないという仮説[81]や、核がすでに凝固してしまっているという仮説などがある。核の状態は硫黄の濃度に大きく依存するが、現時点では不明である[82]。

軌道と公転、自転[編集]

金星は太陽から約0.72AU(1億800万km、6700万mi)離れており、224.7日で一周する。太陽系の全ての惑星は楕円で軌道を公転しているが、金星は軌道離心率が0.01もなく、太陽系の惑星では最も円形に近い軌道を描いている[5]。金星が地球に対して合の時は地球まで4100万kmまで接近する[5]。平均会合周期は約584日である[5]。しかし、地球の周期的な軌道離心率の変化金星との最接近距離は数千年単位で変動する。西暦1年から西暦5383年までに526回、金星は地球から4000万km以内に接近する。しかしそれ以降から西暦6万158年までは4000万km以内に接近する事はないとされている[83]。

太陽系を北極から見ると、全ての惑星は反時計回りに公転している。自転もほとんどの惑星が反時計回りに自転しているが、金星だけ時計回りに公転しており、また自転周期が243日と、太陽系の中で一番長い[84]。金星は自転が遅いので、極めて球に近い形をしている[85]。金星の恒星日は金星年(224.7日)よりも長くなっている。地球の赤道での自転速度は時速1670km(時速1040mph)にもなるが、金星の赤道での自転速度はわずか時速6.5km(時速4.5mph)しかない[86]。マゼラン計画とビーナス・エクスプレスの観測で、金星の自転が徐々に減速している事が分かっている[87]。2012年にはビーナス・エクスプレスから得られたデータにより、16年前より6.5分も自転が長くなっている事が分かった[88]。金星は逆行で自転しているので、太陽日は116.75地球日と、恒星日よりも大幅に短くなっている[89]。ちなみに、金星の太陽日は水星の太陽日(176日)よりも短い。1金星年は、1.92太陽年になる[90]。金星から太陽を見ると、逆行で自転しているので西から太陽が昇り、東に沈むように見えるはずである[90]。しかし、金星の表面は分厚い雲で覆われているので、まず太陽は観測出来ないであろう[91]。

金星は、原始惑星系円盤から、現在とは異なる公転周期、公転軌道を持って誕生し、その後数十億年かけて、他の惑星との摂動や潮汐力などによって現在の軌道に落ち着いているとされている。金星の遅い自転は、自転を遅くさせる傾向がある太陽の重力と、厚い金星大気と太陽熱との摩擦による大気潮汐の平衡によって生じていると考えられている[92][93]。金星が地球に最接近する周期は584日で、これは金星の恒星日の5倍にほぼ等しい[94]が、地球と軌道共鳴にあるという仮説は否定されている[95]。

金星は天然の衛星を持っていない[96]。しかし、いくつかのトロヤ群小惑星が発見されている。そのうちの1つである2002 VE68は金星の準衛星でもある[97][98]。他にも一時的なトロヤ群小惑星として、2001 CK32と2012 XE133の2つがある[99]。17世紀にジョヴァンニ・カッシーニの観測によって、金星にネイトと名付けられた衛星が発見された。その後、約200年に渡ってネイトの存在が報告されたが、そのほとんどは近くに見えた恒星を誤って観測してしまったものだった。2006年、カリフォルニア工科大学のAlex AlemiとDavid J. Stevensonsによる初期の太陽系の形成モデルでは、金星は数十億年前にジャイアント・インパクト(巨大衝突)を起こし、衛星が1つ形成された可能性が示された[100]。しかし、この研究では、約1000万年後に他の衝突が起きて、金星の自転方向が逆転し、その潮汐加速によって、衛星は金星に近づいていき、最終的に衝突してしまう事が判明した[101]。現在では、ネイトの存在は全面的に否定されている。

観測[編集]

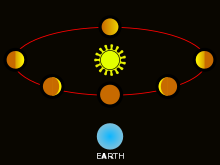

肉眼では、金星は、太陽を除いた恒星と他の惑星よりも明るく輝いて観測される[102]。見かけの明るさも最大光度は−4.89等で[3]、金星が内合の約5週間後[103][104]に起きる、三日月状に観測される時に最大光度となる。これは軌道径の(地球軌道に対する相対的な)長さに関係しており、水星とは異なる。金星の背後から太陽光が差し込むと、明るさは-3等級まで下がる[4]。金星は、晴れた日中の空でも観測出来るほど明るく[105]、太陽が地平線付近にあると、より容易に観測が出来る。金星は内惑星なので、太陽からの離角は常に47度以内の位置で観測される[106]

地球と金星の会合周期は583.92日(約1年7か月)であり、内合から外合までの約9か月半は日の出より早く金星が東の空に昇るため「明けの明星」となる(ただし内合・外合の前後は太陽に近すぎるため、太陽の強い光に紛れて肉眼で確認することは極めて困難である)。内合から約10週間後[103]に西方最大離角となる。外合を過ぎると日没より遅く金星が西の空に沈むため「宵の明星」となり、東方最大離角、最大光度を経て内合に戻る。

その神秘的な明るい輝きは、古代より人々の心に強い印象を残していたようで、それぞれの民族における神話の中で象徴的な存在の名が与えられていることが多い。また地域によっては早くから、明けの明星と宵の明星が同一の星であることも認識されていた。

朔望[編集]

地球から見た金星は、月のような満ち欠けの相が見られる。これは内惑星共通の性質で、水星も同じである。内合の時に「新金星」、外合の時に「満金星」となる。内合のときに完全に太陽と同じ方向に見える場合、金星の太陽面通過と呼ばれる現象がまれに起こる。最大離角の時には半分欠けた形になる。西方最大離角の時には日の出前に最も早く上り、東方最大離角の時には日没後に最も遅く沈む。

金星による影[編集]

金星が最も明るく輝く時期には、金星の光による影ができることがある。オーストラリアの砂漠では地面に映る自分の影が見えたり[107]、日本でも白い紙の上に手をかざすと影ができたりする[108]。なお、過去には SN 1006 のような超新星が地球上の物体に影を生じさせた記録も残っているが、現在観測できるそれほど明るい天体は太陽、月、金星、天の川のみ[108]である。

金星の太陽面通過[編集]

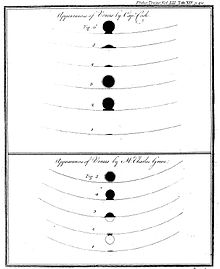

金星の軌道は、地球に対してわずかに傾いている。したがって、金星が地球と太陽の間を通過しても、通常は太陽面を通過する事はない。しかし、金星の合が、地球の軌道面上で発生すると、金星の太陽面通過が起きる。金星の太陽面通過は現在、243年の周期で繰り返されており、8年、105.5年、8年、121.5年の間隔で発生する。金星の太陽面通過は、天文学者のエレミア・ホロックスによって初めて観測された[109]。

最も最近に観測された8年間隔の太陽面通過は、2004年6月8日[110]と2012年6月6日[111]に発生した。金星の太陽面通過の様子は多くのアウトレットオンラインなどからのライブ中継でも見る事が出来る[112]。

はっきりとした観測記録が残っている8年間隔の太陽面通過は1874年12月と1882年12月で、次に発生する8年間隔の太陽面通過は2117年12月11日と2125年12月8日である[113]。世界で最も古い映画は1874年にフランスで製作されたPassage de Venusで、1874年に発生した金星の太陽面通過を説明しているものだった。天文学の歴史において、金星の太陽面通過は、1639年のホロックスの観測から、天文単位の長さや太陽系の大きさを調べる事が出来る事が示されたため、とても重要視されてきた[114]。太平洋を航海したジェームズ・クックは、王立協会からの指令で、1769年に起こる金星の太陽面通過を観測するために、1768年にタヒチ島に上陸して、観測を行った[115][116]。

日中の観測[編集]

金星を日中で観測したという記録や逸話がいくつも残されている。天文学者エドモンド・ハレーは、1716年に、昼間のロンドンで多くの人が金星を観測した際、金星の最大光度を計算した。また、フランスの皇帝ナポレオン・ボナパルトは、ルクセンブルクのレセプションで、昼間に金星とおぼしき惑星を目撃した[117]。惑星が昼間に観測された歴史的な記録として、1865年3月4日にワシントンD.C.で行われたアブラハム・リンカーン大統領の演説中での観測がある[118]。三日月状の金星が日中に観測出来るかどうかは、今も議論されている[119]。

アシェン光[編集]

金星の長年の謎の1つとして、アシェン光と呼ばれる発光現象がある。アシェン光は、金星が三日月状に見える時の夜側で観測されるとされている。最初の報告は1643年になされたが、現在もその存在は確認されていない。観測者は、金星の大気中の電気活動から生じていると推測しているが、明るい三日月状の物体を観察する際、生理学的効果の結果として引き起こされた幻想であるとされている[120]。

研究[編集]

古代の研究[編集]

金星は古代文明において、明けの明星と宵の明星をそれぞれ、「朝星」「夕方星」と呼ばれ、この名称は、2つが全く異なる天体だとして認識されていた事を反映している。しかし、紀元前17世紀頃に編纂されたと思われるVenus tablet of Ammisaduqa[121]では、古代バビロニア人がこの2つの星が同じものである事を発見しており、「空の明るい女王」と呼ばれていた事が示されている[122]。古代ギリシャでは、2つの星は異なるものだと考えれ、それぞれをポースポロスとヘスペロスだと考えていた。ガイウス・プリニウス・セクンドゥス。中国では、明けの明星は太白、あるいは啟明と呼び、宵の明星は長庚と呼ばれた。古代ローマでは、明けの明星はルシファー、宵の明星はヴェスパーだと考えていた。

2世紀の天文学者プトレマイオスは、アルマゲストで、水星と金星が、地球と太陽の間を公転している事を理論から主張した。11世紀のペルシャの天文学者イブン・スィーナーは、初めて金星の太陽面通過を観測したと主張し[123]、後の天文学者は、プトレマイオスの理論が正しい事を証明していった[124]。12世紀には、アンダルスの天文学者イブン・バーッジャが太陽の前を2つの惑星が通過している様子を観測し、13世紀にそれが水星と金星の同時太陽面通過であった事が、イランの天文学者Qutb al-Din al-Shiraziによって明らかとなった[125]。

When the Italian physicist Galileo Galilei first observed the planet in the early 17th century, he found it showed phases like the Moon, varying from crescent to gibbous to full and vice versa. When Venus is furthest from the Sun in the sky, it shows a half-lit phase, and when it is closest to the Sun in the sky, it shows as a crescent or full phase. This could be possible only if Venus orbited the Sun, and this was among the first observations to clearly contradict the Ptolemaic geocentric model that the Solar System was concentric and centred on Earth.[126][127]

The 1639 transit of Venus was accurately predicted by Jeremiah Horrocks and observed by him and his friend, William Crabtree, at each of their respective homes, on 4 December 1639 (24 November under the Julian calendar in use at that time).[128]

The atmosphere of Venus was discovered in 1761 by Russian polymath Mikhail Lomonosov.[129][130] Venus's atmosphere was observed in 1790 by German astronomer Johann Schröter. Schröter found when the planet was a thin crescent, the cusps extended through more than 180°. He correctly surmised this was due to scattering of sunlight in a dense atmosphere. Later, American astronomer Chester Smith Lyman observed a complete ring around the dark side of the planet when it was at inferior conjunction, providing further evidence for an atmosphere.[131] The atmosphere complicated efforts to determine a rotation period for the planet, and observers such as Italian-born astronomer Giovanni Cassini and Schröter incorrectly estimated periods of about 24 h from the motions of markings on the planet's apparent surface.[132]

地上からの観測[編集]

Little more was discovered about Venus until the 20th century. Its almost featureless disc gave no hint what its surface might be like, and it was only with the development of spectroscopic, radar and ultraviolet observations that more of its secrets were revealed. The first ultraviolet observations were carried out in the 1920s, when Frank E. Ross found that ultraviolet photographs revealed considerable detail that was absent in visible and infrared radiation. He suggested this was due to a dense, yellow lower atmosphere with high cirrus clouds above it.[133]

Spectroscopic observations in the 1900s gave the first clues about the Venusian rotation. Vesto Slipher tried to measure the Doppler shift of light from Venus, but found he could not detect any rotation. He surmised the planet must have a much longer rotation period than had previously been thought.[134] Later work in the 1950s showed the rotation was retrograde. Radar observations of Venus were first carried out in the 1960s, and provided the first measurements of the rotation period, which were close to the modern value.[135]

Radar observations in the 1970s revealed details of the Venusian surface for the first time. Pulses of radio waves were beamed at the planet using the 300 m (980 ft) radio telescope at Arecibo Observatory, and the echoes revealed two highly reflective regions, designated the Alpha and Beta regions. The observations also revealed a bright region attributed to mountains, which was called Maxwell Montes.[136] These three features are now the only ones on Venus that do not have female names.[31]

探査[編集]

The first robotic space probe mission to Venus, and the first to any planet, began with the Soviet Venera program in 1961.[137] The United States' exploration of Venus had its first success with the Mariner 2 mission on 14 December 1962, becoming the world's first successful interplanetary mission, passing 34,833 km (21,644 mi) above the surface of Venus, and gathering data on the planet's atmosphere.[138][139]

On 18 October 1967, the Soviet Venera 4 successfully entered the atmosphere and deployed science experiments. Venera 4 showed the surface temperature was hotter than Mariner 2 had calculated, at almost 500 °C, determined that the atmosphere is 95% carbon dioxide (CO2), and discovered that Venus's atmosphere was considerably denser than Venera 4's designers had anticipated.[140] The joint Venera 4–Mariner 5 data were analysed by a combined Soviet–American science team in a series of colloquia over the following year,[141] in an early example of space cooperation.[142]

In 1974, Mariner 10 swung by Venus on its way to Mercury and took ultraviolet photographs of the clouds, revealing the extraordinarily high wind speeds in the Venusian atmosphere.

In 1975, the Soviet Venera 9 and 10 landers transmitted the first images from the surface of Venus, which were in black and white. In 1982 the first colour images of the surface were obtained with the Soviet Venera 13 and 14 landers.

NASA obtained additional data in 1978 with the Pioneer Venus project that consisted of two separate missions:[143] Pioneer Venus Orbiter and Pioneer Venus Multiprobe.[144] The successful Soviet Venera program came to a close in October 1983, when Venera 15 and 16 were placed in orbit to conduct detailed mapping of 25% of Venus's terrain (from the north pole to 30°N latitude)[145]

Several other Venus flybys took place in the 1980s and 1990s that increased the understanding of Venus, including Vega 1 (1985), Vega 2 (1985), Galileo (1990), Magellan (1994), Cassini–Huygens (1998), and MESSENGER (2006). Then, Venus Express by the European Space Agency (ESA) entered orbit around Venus in April 2006. Equipped with seven scientific instruments, Venus Express provided unprecedented long-term observation of Venus's atmosphere. ESA concluded that mission in December 2014.

As of 2016, Japan's Akatsuki is in a highly elliptical orbit around Venus since 7 December 2015, and there are several probing proposals under study by Roscosmos, NASA, and India's ISRO.

In 2016, NASA announced that it was planning a rover, the Automaton Rover for Extreme Environments, designed to survive for an extended time in Venus's environmental conditions. It would be controlled by a mechanical computer and driven by wind power.[146]

探査機の一覧[編集]

This is a list of attempted and successful spacecraft that have left Earth to explore Venus more closely.[147] Venus has also been imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope in Earth orbit, and distant telescopic observations are another source of information about Venus.

| Responsible | Mission | Launch | Elements and result | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USSR |

Sputnik 7 | 1961年2月4日 | Impact (attempted) | |

| USSR |

Venera 1 | 1961年2月12日 | Flyby (contact lost) | |

| USA |

Mariner 1 | 1962年7月22日 | Flyby (launch failure) | |

| USSR |

Sputnik 19 | 1962年8月25日 | Flyby (attempted) | |

| USA |

Mariner 2 | 1962年8月27日 | Flyby | First successful planetary flyby[148] |

| USSR |

Sputnik 20 | 1962年9月1日 | Flyby (attempted) | |

| USSR |

Sputnik 21 | 1962年9月12日 | Flyby (attempted) | |

| USSR |

Cosmos 21 | 1963年11月11日 | Attempted Venera test flight? | |

| USSR |

Venera 1964A | 1964年2月19日 | Flyby (launch failure) | |

| USSR |

Venera 1964B | 1964年3月1日 | Flyby (launch failure) | |

| USSR |

Cosmos 27 | 1964年3月27日 | Flyby (attempted) | |

| USSR |

Zond 1 | 1964年4月2日 | Flyby (contact lost) | |

| USSR |

Venera 2 | 1965年11月12日 | Flyby (contact lost) | |

| USSR |

Venera 3 | 1965年11月16日 | Atmospheric probe (contact lost) | |

| USSR |

Cosmos 96 | 1965年11月23日 | Lander (attempted?) | |

| USSR |

Venera 1965A | 1965年11月23日 | Flyby (launch failure) | |

| USSR |

Venera 4 | 1967年6月12日 | Atmospheric probe | |

| USA |

Mariner 5 | 1967年6月14日 | Flyby | |

| USSR |

Cosmos 167 | 1967年6月17日 | Probe (attempted) | |

| USSR |

Venera 5 | 1969年1月5日 | Atmospheric probe | |

| USSR |

Venera 6 | 1969年1月10日 | Atmospheric probe | |

| USSR |

Venera 7 | 1970年8月17日 | Lander | First ever successful landing on another planet; transmitted from surface for 23 minutes |

| USSR |

Cosmos 359 | 1970年8月22日 | Probe (attempted) | |

| USSR |

Venera 8 | 1972年3月27日 | Lander | |

| USSR |

Cosmos 482 | 1972年3月31日 | Probe (attempted) | |

| USA |

Mariner 10 | 1973年11月4日 | Flyby | Mercury flyby |

| USSR |

Venera 9 | 1975年6月8日 | Orbiter and lander | First ever photograph of the surface of another planet |

| USSR |

Venera 10 | 1975年6月14日 | Orbiter and lander | |

| USA |

Pioneer Venus 1 | 1978年5月20日 | Orbiter | |

| USA |

Pioneer Venus 2 | 1978年8月8日 | Atmospheric probes | |

| USSR |

Venera 11 | 1978年9月9日 | Flyby bus and lander | |

| USSR |

Venera 12 | 1978年9月14日 | Flyby bus and lander | |

| USSR |

Venera 13 | 1981年10月30日 | Flyby bus and lander | First ever colour photograph of the surface of Venus |

| USSR |

Venera 14 | 1981年11月4日 | Flyby bus and lander | |

| USSR |

Venera 15 | 1983年6月2日 | Orbiter | |

| USSR |

Venera 16 | 1983年6月7日 | Orbiter | |

| USSR |

Vega 1 | 1984年12月15日 | Lander and balloon | Comet Halley flyby |

| USSR |

Vega 2 | 1984年12月21日 | Lander and balloon | Comet Halley flyby |

| USA |

Magellan | 1989年5月4日 | Orbiter | |

| USA |

Galileo | 1989年10月18日 | Flyby | Jupiter orbiter/probe |

| USA |

Cassini | 1997年10月15日 | Flyby (x2) | In 1998 and 1999; Saturn orbiter[149] |

| USA |

MESSENGER | 2004年8月3日 | Flyby (x2) | Mercury orbiter |

| ESA |

Venus Express | 2005年11月9日 | Orbiter | |

| JPN |

Akatsuki | 2010年12月7日 | Orbiter | Successful orbit insertion reattempt on 7 December 2015 |

| ESA JPN |

BepiColombo | January 2017 (planned) |

Two flybys planned | Planned Mercury orbiter |

| RUS |

Venera-D | 2020s | Orbiter and lander | Proposed mission[150] |

文化における金星[編集]

See also Venus (mythology), Venus (astrology) and Historical observations and impact

Venus is a primary feature of the night sky, and so has been of remarkable importance in mythology, astrology and fiction throughout history and in different cultures. Classical poets such as Homer, Sappho, Ovid and Virgil spoke of the star and its light.[151] Romantic poets such as William Blake, Robert Frost, Alfred Lord Tennyson and William Wordsworth wrote odes to it.[152] With the invention of the telescope, the idea that Venus was a physical world and possible destination began to take form.

The impenetrable Venusian cloud cover gave science fiction writers free rein to speculate on conditions at its surface; all the more so when early observations showed that not only was it similar in size to Earth, it possessed a substantial atmosphere. Closer to the Sun than Earth, the planet was frequently depicted as warmer, but still habitable by humans.[153] The genre reached its peak between the 1930s and 1950s, at a time when science had revealed some aspects of Venus, but not yet the harsh reality of its surface conditions. Findings from the first missions to Venus showed the reality to be quite different, and brought this particular genre to an end.[154] As scientific knowledge of Venus advanced, so science fiction authors tried to keep pace, particularly by conjecturing human attempts to terraform Venus.[155]

惑星記号[編集]

The astronomical symbol for Venus is the same as that used in biology for the female sex: a circle with a small cross beneath.[156] The Venus symbol also represents femininity, and in Western alchemy stood for the metal copper.[156] Polished copper has been used for mirrors from antiquity, and the symbol for Venus has sometimes been understood to stand for the mirror of the goddess.[156]

The astronomical symbol for Venus is the same as that used in biology for the female sex: a circle with a small cross beneath.[156] The Venus symbol also represents femininity, and in Western alchemy stood for the metal copper.[156] Polished copper has been used for mirrors from antiquity, and the symbol for Venus has sometimes been understood to stand for the mirror of the goddess.[156]

植民地化とテラフォーミング[編集]

Due to its extremely hostile conditions, a surface colony on Venus is not possible with current technology. The atmospheric pressure and temperature approximately fifty kilometres above the surface are similar to those at Earth's surface. In Venus's mostly carbon dioxide atmosphere, Earth's air (nitrogen and oxygen) would act as a lifting gas. This has led to proposals for "floating cities" in the Venusian atmosphere.[157] Aerostats (lighter-than-air balloons) could be used for initial exploration and ultimately for permanent settlements.[157] Among the many engineering challenges are the dangerous amounts of sulfuric acid at these heights.[157]

|

|

|

|

関連項目[編集]

脚注[編集]

注釈[編集]

出典[編集]

- ^ a b “金星ってどんな星?”. AstroArts. 2016年2月28日閲覧。

- ^ “金星の概要”. JAXA. 2016年3月1日閲覧。

- ^ a b “HORIZONS Web-Interface for Venus (Major Body=299)”. JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System (2006年2月27日). 2017年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ a b Mallama, A. (2011). “Planetary magnitudes”. Sky & Telescope 121 (1): 51–56.

- ^ a b c d “Venus Fact Sheet”. NASA. 2016年2月28日閲覧。

- ^ Yeomans, Donald K.. “HORIZONS Web-Interface for Venus (Major Body=2)”. JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System. 2016年2月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b Simon, J.L.; Bretagnon, P.; Chapront, J.; Chapront-Touzé, M.; Francou, G.; Laskar, J. (February 1994). “Numerical expressions for precession formulae and mean elements for the Moon and planets”. Astronomy and Astrophysics 282 (2): 663–683. Bibcode: 1994A&A...282..663S.

- ^ Seidelmann, P. Kenneth; Archinal, Brent A.; A'Hearn, Michael F. (2007). “Report of the IAU/IAG Working Group on cartographic coordinates and rotational elements: 2006”. Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 98 (3): 155–180. Bibcode: 2007CeMDA..98..155S. doi:10.1007/s10569-007-9072-y.

- ^ Konopliv, A. S.; Banerdt, W. B.; Sjogren, W. L. (May 1999). “Venus Gravity: 180th Degree and Order Model”. Icarus 139 (1): 3–18. Bibcode: 1999Icar..139....3K. doi:10.1006/icar.1999.6086.

- ^ “Planets and Pluto: Physical Characteristics”. NASA (2008年11月5日). 2016年2月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Venus: Facts & Figures”. NASA. 2007年4月12日閲覧。

- ^ Lawrence, Pete (2005年). “In Search of the Venusian Shadow”. Digitalsky.org.uk. 2012年6月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年3月1日閲覧。

- ^ 田舎移住者の星日記

- ^ Hashimoto, G. L.; Roos-Serote, M.; Sugita, S.; Gilmore, M. S.; Kamp, L. W.; Carlson, R. W.; Baines, K. H. (2008). “Felsic highland crust on Venus suggested by Galileo Near-Infrared Mapping Spectrometer data”. Journal of Geophysical Research, Planets 113: E00B24. Bibcode: 2008JGRE..11300B24H. doi:10.1029/2008JE003134.

- ^ David Shiga (2007年10月10日). “Did Venus's ancient oceans incubate life?”. New Scientist. 2016年3月1日閲覧。

- ^ Jakosky, Bruce M. (1999). “Atmospheres of the Terrestrial Planets”. In Beatty, J. Kelly; Petersen, Carolyn Collins; Chaikin, Andrew. The New Solar System (4th ed.). Boston: Sky Publishing. pp. 175–200. ISBN 978-0-933346-86-4. OCLC 39464951

- ^ “Caught in the wind from the Sun”. European Space Agency (2007年11月28日). 2008年7月12日閲覧。

- ^ Evans, James (1998). The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy. Oxford University Press. pp. 296–7. ISBN 978-0-19-509539-5 2016年3月1日閲覧。

- ^ Lopes, Rosaly M. C.; Gregg, Tracy K. P. (2004). Volcanic worlds: exploring the Solar System's volcanoes. Springer Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-3-540-00431-8

- ^ “Atmosphere of Venus”. The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflght. 2016年3月2日閲覧。

- ^ Mueller, Nils (2014). “Venus Surface and Interior”. In Tilman, Spohn; Breuer, Doris; Johnson, T. V.. Encyclopedia of the Solar System (3rd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier Science & Technology. ISBN 978-0-12-415845-0 2016年3月2日閲覧。

- ^ Esposito, Larry W. (1984-03-09). “Sulfur Dioxide: Episodic Injection Shows Evidence for Active Venus Volcanism”. Science 223 (4640): 1072–1074. Bibcode: 1984Sci...223.1072E. doi:10.1126/science.223.4640.1072. PMID 17830154 2016年3月2日閲覧。.

- ^ Bullock, Mark A.; Grinspoon, David H. (March 2001). “The Recent Evolution of Climate on Venus”. Icarus 150 (1): 19–37. Bibcode: 2001Icar..150...19B. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6570.

- ^ Basilevsky, Alexander T.; Head, James W., III (1995). “Global stratigraphy of Venus: Analysis of a random sample of thirty-six test areas”. Earth, Moon, and Planets 66 (3): 285–336. Bibcode: 1995EM&P...66..285B. doi:10.1007/BF00579467.

- ^ a b c Nimmo, F.; McKenzie, D. (1998). “Volcanism and Tectonics on Venus”. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 26 (1): 23–53. Bibcode: 1998AREPS..26...23N. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.26.1.23.

- ^ a b Strom, Robert G.; Schaber, Gerald G.; Dawson, Douglas D. (25 May 1994). “The global resurfacing of Venus”. Journal of Geophysical Research 99 (E5): 10899–10926. Bibcode: 1994JGR....9910899S. doi:10.1029/94JE00388.

- ^ 「Newton別冊 探査機が明らかにした太陽系のすべて」p14 ニュートンプレス 2006年11月15日発行

- ^ 「ISASコラム 内惑星探訪 第8回:電波を通して眺めた金星の地形」佐々木晶 宇宙航空研究開発機構 2015年10月25日閲覧

- ^ a b Frankel, Charles (1996). Volcanoes of the Solar System. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47770-3

- ^ Batson, R.M.; Russell J. F. (18–22 March 1991). "Naming the Newly Found Landforms on Venus" (PDF). Proceedings of the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference XXII. Houston, Texas. p. 65. 2016年3月5日閲覧。

- ^ a b Carolynn Young, ed (1 August 1990). The Magellan Venus Explorer's Guide. California: Jet Propulsion Laboratory. p. 93 2016年3月5日閲覧。

- ^ Kranopol'skii, V. A. (1980). “Lightning on Venus according to Information Obtained by the Satellites Venera 9 and 10”. Cosmic Research 18 (3): 325–330. Bibcode: 1980CosRe..18..325K.

- ^ Russell, C. T.; Phillips, J. L. (1990). “The Ashen Light”. Advances in Space Research 10 (5): 137–141. Bibcode: 1990AdSpR..10..137R. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(90)90174-X.

- ^ “Venera 12 Descent Craft”. National Space Science Data Center. NASA. 2016年3月9日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Russell, C. T.; Zhang, T. L.; Delva, M.; Magnes, W.; Strangeway, R. J.; Wei, H. Y. (November 2007). “Lightning on Venus inferred from whistler-mode waves in the ionosphere”. Nature 450 (7170): 661–662. Bibcode: 2007Natur.450..661R. doi:10.1038/nature05930. PMID 18046401.

- ^ “Venus also zapped by lightning”. CNN.com. (2007年11月29日). オリジナルの2007年11月30日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2016年3月9日閲覧。

- ^ Bauer, Markus (2012年12月3日). “Have Venusian volcanoes been caught in the act?”. European Space Agency. 2013年11月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2015年6月20日閲覧。

- ^ Glaze, Lori S. (August 1999). “Transport of SO2 by explosive volcanism on Venus”. Journal of Geophysical Research 104 (E8): 18899–18906. Bibcode: 1999JGR...10418899G. doi:10.1029/1998JE000619.

- ^ Marcq, Emmanuel; Bertaux, Jean-Loup; Montmessin, Franck; Belyaev, Denis (January 2013). “Variations of sulphur dioxide at the cloud top of Venus's dynamic atmosphere”. Nature Geoscience 6 (1): 25–28. Bibcode: 2013NatGe...6...25M. doi:10.1038/ngeo1650.

- ^ “Ganis Chasma”. Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Science Center. 2016年3月9日閲覧。

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (2015年6月18日). “Transient hot spots on Venus: Best evidence yet for active volcanism”. The Planetary Society. 2016年3月9日閲覧。

- ^ “Hot lava flows discovered on Venus”. European Space Agency (2015年6月18日). 2015年6月19日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年3月9日閲覧。

- ^ Shalygin, E. V.; Markiewicz, W. J.; Basilevsky, A. T.; Titov, D. V.; Ignatiev, N. I.; Head, J. W. (17 June 2015). “Active volcanism on Venus in the Ganiki Chasma rift zone”. Geophysical Research Letters 42: 4762–4769. Bibcode: 2015GeoRL..42.4762S. doi:10.1002/2015GL064088.

- ^ Herrick, R. R.; Phillips, R. J. (1993). “Effects of the Venusian atmosphere on incoming meteoroids and the impact crater population”. Icarus 112 (1): 253–281. Bibcode: 1994Icar..112..253H. doi:10.1006/icar.1994.1180.

- ^ Morrison, David; Owens, Tobias C. (2003). The Planetary System (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-8734-6

- ^ Goettel, K. A.; Shields, J. A.; Decker, D. A. (16–20 March 1981). "Density constraints on the composition of Venus". Proceedings of the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Houston, TX: Pergamon Press. pp. 1507–1516. Bibcode:1982LPSC...12.1507G. 2016年3月18日閲覧。

- ^ Faure, Gunter; Mensing, Teresa M. (2007). Introduction to planetary science: the geological perspective. Springer eBook collection. Springer. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4020-5233-0

- ^ Aitta, A. (April 2012), “Venus' internal structure, temperature and core composition”, Icarus 218 (2): 967−974, Bibcode: 2012Icar..218..967A, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2012.01.007 2016年3月23日閲覧。.

- ^ a b “金星にプレートテクトニクスが存在しない原因について新たな粘性構造モデルを提唱!”. 広島大学 (2014年3月12日). 2016年3月23日閲覧。

- ^ Taylor, Fredric W. (2014). “Venus: Atmosphere”. In Tilman, Spohn; Breuer, Doris; Johnson, T. V.. Encyclopedia of the Solar System. Oxford: Elsevier Science & Technology. ISBN 978-0-12-415845-0 2016年1月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Venus”. Case Western Reserve University (2006年9月13日). 2012年4月26日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年4月30日閲覧。

- ^ 「太陽系探検ガイド エクストリームな50の場所」p95 デイヴィッド・ベイカー、トッド・ラトクリフ著 渡部潤一監訳 後藤真理子訳 朝倉書店 2012年10月10日初版第1刷

- ^ Lewis, John S. (2004). Physics and Chemistry of the Solar System (2nd ed.). Academic Press. p. 463. ISBN 978-0-12-446744-6

- ^ Henry Bortman (2004年). “Was Venus Alive? 'The Signs are Probably There'”. Space.com. 2016年4月30日閲覧。

- ^ Hammonds, Markus (2013年5月16日). “Does Alien Life Thrive in Venus's Mysterious Clouds?”. Discovery News. 2016年4月30日閲覧。

- ^ Mullen, Leslie (2002年11月13日). “Venusian Cloud Colonies”. Astrobiology Magazine. 2014年8月16日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年10月16日閲覧。

- ^ Landis, Geoffrey A. (July 2003). “Astrobiology: The Case for Venus”. Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 56 (7-8): 250–254. NASA/TM—2003-212310. オリジナルの7 August 2011時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Cockell, Charles S. (December 1999). “Life on Venus”. Planetary and Space Science 47 (12): 1487–1501. Bibcode: 1999P&SS...47.1487C. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(99)00036-7.

- ^ Krasnopolsky, V. A.; Parshev, V. A. (1981). “Chemical composition of the atmosphere of Venus”. Nature 292 (5824): 610–613. Bibcode: 1981Natur.292..610K. doi:10.1038/292610a0.

- ^ Krasnopolsky, Vladimir A. (2006). “Chemical composition of Venus atmosphere and clouds: Some unsolved problems”. Planetary and Space Science 54 (13–14): 1352–1359. Bibcode: 2006P&SS...54.1352K. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2006.04.019.

- ^ W. B. Rossow; A. D. del Genio; T. Eichler (1990). “Cloud-tracked winds from Pioneer Venus OCPP images” (PDF). Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 47 (17): 2053–2084. Bibcode: 1990JAtS...47.2053R. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1990)047<2053:CTWFVO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0469.

- ^ Normile, Dennis (7 May 2010). “Mission to probe Venus's curious winds and test solar sail for propulsion”. Science 328 (5979): 677. Bibcode: 2010Sci...328..677N. doi:10.1126/science.328.5979.677-a. PMID 20448159.

- ^ Lorenz, Ralph D. (2001年). “Titan, Mars and Earth: Entropy Production by Latitudinal Heat Transport” (PDF). Ames Research Center, University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. 2016年5月22日閲覧。

- ^ “Interplanetary Seasons”. NASA. 2016年5月22日閲覧。

- ^ Basilevsky A. T.; Head J. W. (2003). “The surface of Venus”. Reports on Progress in Physics 66 (10): 1699–1734. Bibcode: 2003RPPh...66.1699B. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/66/10/R04.

- ^ McGill, G. E.; Stofan, E. R.; Smrekar, S. E. (2010). “Venus tectonics”. In T. R. Watters; R. A. Schultz. Planetary Tectonics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 81–120. ISBN 978-0-521-76573-2

- ^ Hand, Eric (November 2007). “European mission reports from Venus”. Nature (450): 633–660. doi:10.1038/news.2007.297.

- ^ Staff (2007年11月28日). “Venus offers Earth climate clues”. BBC News 2007年11月29日閲覧。

- ^ AstroArts ビーナス・エクスプレスが金星の南極に巨大な渦を発見 AstroArts

- ^ AstroArts ビーナス・エクスプレス、金星大気にオゾン層を発見

- ^ “ESA finds that Venus has an ozone layer too”. European Space Agency (2011年10月6日). 2011年12月25日閲覧。

- ^ A curious cold layer in the atmosphere of Venus ESA

- ^ “When A Planet Behaves Like A Comet”. European Space Agency (2013年1月29日). 2016年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ Kramer, Miriam (2013年1月30日). “Venus Can Have 'Comet-Like' Atmosphere”. Space.com. 2016年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ “太陽風の凪にたなびく金星の電離圏”. AstroArts (2013年1月30日). 2016年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ “The HITRAN Database”. Atomic and Molecular Physics Division, ハーバード・スミソニアン天体物理学センター. 2016年7月3日閲覧。 “HITRAN is a compilation of spectroscopic parameters that a variety of computer codes use to predict and simulate the transmission and emission of light in the atmosphere.”

- ^ “HITRAN on the Web Information System”. V.E. Zuev Institute of Atmospheric Optics. 2016年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ Dolginov, Sh.; Eroshenko, E. G.; Lewis, L. (September 1969). “Nature of the Magnetic Field in the Neighborhood of Venus”. Cosmic Research 7: 675. Bibcode: 1969CosRe...7..675D.

- ^ Kivelson G. M.; Russell, C. T. (1995). Introduction to Space Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45714-9.

- ^ Upadhyay, H. O.; Singh, R. N. (April 1995). “Cosmic ray Ionization of Lower Venus Atmosphere”. Advances in Space Research 15 (4): 99–108. Bibcode: 1995AdSpR..15...99U. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(94)00070-H.

- ^ Konopliv, A. S.; Yoder, C. F. (1996). “Venusian k2 tidal Love number from Magellan and PVO tracking data”. Geophysical Research Letters 23 (14): 1857–1860. Bibcode: 1996GeoRL..23.1857K. doi:10.1029/96GL01589. オリジナルの12 May 2011時点におけるアーカイブ。 2009年7月12日閲覧。.

- ^ Nimmo, Francis (November 2002). “Why does Venus lack a magnetic field?” (PDF). Geology 30 (11): 987–990. Bibcode: 2002Geo....30..987N. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0987:WDVLAM>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613 2016年10月16日閲覧。.

- ^ Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 archiveurl と archivedate は両方を指定してください。“Venus Close Approaches to Earth as predicted by Solex 11”. 2012年8月9日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年10月16日閲覧。 Numbers generated by Solex

- ^ 「Newton別冊 探査機が明らかにした太陽系のすべて」p14 ニュートンプレス 2006年11月15日発行

- ^ Squyres, Steven W. (2016年). “Venus”. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2016年10月16日閲覧。

- ^ Bakich, Michael E. (2000). The Cambridge Planetary Handbook. Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-521-63280-5

- ^ “Could Venus Be Shifting Gear?”. Venus Express. European Space Agency (2012年2月10日). 2016年10月16日閲覧。

- ^ 金星の自転速度が低下? ナショナルジオグラフィックニュース

- ^ “Planetary Facts”. The Planetary Society. 2012年5月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年10月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Space Topics: Compare the Planets”. The Planetary Society. 2006年2月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年10月16日閲覧。

- ^ Serge Brunier (2002). Solar System Voyage. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-521-80724-1

- ^ Correia, Alexandre C. M.; Laskar, Jacques; De Surgy, Olivier Néron (May 2003). “Long-Term Evolution of the Spin of Venus, Part I: Theory”. Icarus 163 (1): 1–23. Bibcode: 2003Icar..163....1C. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00042-3.

- ^ Laskar, Jacques; De Surgy, Olivier Néron. “Long-Term Evolution of the Spin of Venus, Part II: Numerical Simulations”. Icarus 163 (1): 24–45. Bibcode: 2003Icar..163...24C. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00043-5.

- ^ Gold, T.; Soter, S. (1969). “Atmospheric Tides and the Resonant Rotation of Venus”. Icarus 11 (3): 356–66. Bibcode: 1969Icar...11..356G. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(69)90068-2.

- ^ Shapiro, I. I.; Campbell, D. B.; De Campli, W. M. (June 1979). “Nonresonance Rotation of Venus”. Astrophysical Journal 230: L123–L126. Bibcode: 1979ApJ...230L.123S. doi:10.1086/182975.

- ^ Sheppard, Scott S.; Trujillo, Chadwick A. (July 2009). “A Survey for Satellites of Venus”. Icarus 202 (1): 12–16. arXiv:0906.2781. Bibcode: 2009Icar..202...12S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.02.008.

- ^ Mikkola, S.; Brasser, R.; Wiegert, P.; Innanen, K. (July 2004). “Asteroid 2002 VE68: A Quasi-Satellite of Venus”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 351 (3): L63. Bibcode: 2004MNRAS.351L..63M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.07994.x.

- ^ De la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; De la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (November 2012). “On the Dynamical Evolution of 2002 VE68”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 427 (1): 728–39. arXiv:1208.4444. Bibcode: 2012MNRAS.427..728D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21936.x.

- ^ De la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; De la Fuente Marcos, Raúl. “Asteroid 2012 XE133: A Transient Companion to Venus”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 432 (2): 886–93. arXiv:1303.3705. Bibcode: 2013MNRAS.432..886D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt454.

- ^ Musser, George (2006年10月10日). “Double Impact May Explain Why Venus Has No Moon”. Scientific American 2017年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ Tytell, David (2006年10月10日). “Why Doesn't Venus Have a Moon?”. Sky & Telescope 2017年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ Dickinson, Terrence (1998). NightWatch: A Practical Guide to Viewing the Universe. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-55209-302-3 2017年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ a b 『天文年鑑』2006年版120頁

- ^ “When is Venus brightest?”. Excelsior Statistics and Optimization. 2017年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ Tony Flanders (2011年2月25日). “See Venus in Broad Daylight!”. Sky & Telescope 2017年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ Espenak, Fred (1996年). “Venus: Twelve year planetary ephemeris, 1995–2006”. NASA Reference Publication 1349. NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. 2017年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ 田舎移住者の星日記

- ^ a b 星影を楽しむ - 渡部潤一

- ^ Template:Cite webの呼び出しエラー:引数 archiveurl と archivedate は両方を指定してください。Anon (2012年7月30日). “Transit of Venus”. History. University of Central Lancashire. 時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2012年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ “【特集】2004年6月8日 金星の日面通過”. AstroArts. 2017年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ “【特集】2012年6月6日 金星の太陽面通過”. AstroArts. 2017年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ “Venus transit: A last-minute guide”. NBC News (2012年6月5日). 2013年6月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ Espenak, Fred (2004年). “Transits of Venus, Six Millennium Catalog: 2000 BCE to 4000 CE”. Transits of the Sun. NASA. 2017年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ Kollerstrom, Nicholas (1998年). “Horrocks and the Dawn of British Astronomy”. University College London. 2017年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ Hornsby, T. (1771). “The quantity of the Sun's parallax, as deduced from the observations of the transit of Venus on June 3, 1769”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 61 (0): 574–579. doi:10.1098/rstl.1771.0054.

- ^ Woolley, Richard (1969). “Captain Cook and the Transit of Venus of 1769”. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 24 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1969.0004. ISSN 0035-9149. JSTOR 530738.

- ^ Chatfield, Chris (2010年). “The Solar System with the naked eye”. The Gallery of Natural Phenomena. 2017年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ Gaherty, Geoff (2012年3月26日). “Planet Venus Visible in Daytime Sky Today: How to See It”. Space.com 2017年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ Goines, David Lance (1995年10月18日). “Inferential Evidence for the Pre-telescopic Sighting of the Crescent Venus”. Goines.net. 2017年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ Baum, R. M. (2000). “The enigmatic ashen light of Venus: an overview”. Journal of the British Astronomical Association 110: 325. Bibcode: 2000JBAA..110..325B.

- ^ Hobson, Russell (2009). The Exact Transmission of Texts in the First Millennium B.C.E. (PDF) (Ph.D.). シドニー大学, Department of Hebrew, Biblical and Jewish Studies.

- ^ Waerden, Bartel (1974). Science awakening II: the birth of astronomy. Springer. p. 56. ISBN 978-90-01-93103-2 2017年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ Goldstein, Bernard R. (March 1972). “Theory and Observation in Medieval Astronomy”. Isis (University of Chicago Press) 63 (1): 39–47 [44]. doi:10.1086/350839.

- ^ “AVICENNA viii. Mathematics and Physical Sciences”. Encyclopedia Iranica. 2017年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ S. M. Razaullah Ansari (2002). History of Oriental Astronomy: Proceedings of the Joint Discussion-17 at the 23rd General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union, Organised by the Commission 41 (History of Astronomy), Held in Kyoto, August 25–26, 1997. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-4020-0657-9

- ^ Palmieri, Paolo (2001). “Galileo and the discovery of the phases of Venus”. Journal for the History of Astronomy 21 (2): 109–129. Bibcode: 2001JHA....32..109P.

- ^ Fegley Jr, B (2003). Heinrich D. Holland; Karl K. Turekian. eds. Venus. Elsevier. pp. 487–507. ISBN 978-0-08-043751-4

- ^ Kollerstrom, Nicholas (2004年). “William Crabtree's Venus transit observation”. Proceedings IAU Colloquium No. 196, 2004. International Astronomical Union. 2012年5月10日閲覧。

- ^ Marov, Mikhail Ya. (2004). D.W. Kurtz (ed.). Mikhail Lomonosov and the discovery of the atmosphere of Venus during the 1761 transit. Proceedings of IAU Colloquium No. 196. Preston, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 209–219. Bibcode:2005tvnv.conf..209M. doi:10.1017/S1743921305001390。

- ^ “Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov”. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2009年7月12日閲覧。

- ^ Russell, H. N. (1899). “The Atmosphere of Venus”. Astrophysical Journal 9: 284–299. Bibcode: 1899ApJ.....9..284R. doi:10.1086/140593.

- ^ Hussey, T. (1832). “On the Rotation of Venus”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2: 78–126. Bibcode: 1832MNRAS...2...78H. doi:10.1093/mnras/2.11.78d.

- ^ Ross, F. E. (1928). “Photographs of Venus”. Astrophysical Journal 68–92: 57. Bibcode: 1928ApJ....68...57R. doi:10.1086/143130.

- ^ Slipher, V. M. (1903). “A Spectrographic Investigation of the Rotation Velocity of Venus”. Astronomische Nachrichten 163 (3–4): 35–52. Bibcode: 1903AN....163...35S. doi:10.1002/asna.19031630303.

- ^ Goldstein, R. M.; Carpenter, R. L. (1963). “Rotation of Venus: Period Estimated from Radar Measurements”. Science 139 (3558): 910–911. Bibcode: 1963Sci...139..910G. doi:10.1126/science.139.3558.910. PMID 17743054.

- ^ Campbell, D. B.; Dyce, R. B.; Pettengill G. H. (1976). “New radar image of Venus”. Science 193 (4258): 1123–1124. Bibcode: 1976Sci...193.1123C. doi:10.1126/science.193.4258.1123. PMID 17792750.

- ^ Mitchell, Don (2003年). “Inventing The Interplanetary Probe”. The Soviet Exploration of Venus. 2007年12月27日閲覧。

- ^ Mayer; McCullough; Sloanaker (January 1958). “Observations of Venus at 3.15-cm Wave Length”. The Astrophysical Journal 127: 1. Bibcode: 1958ApJ...127....1M. doi:10.1086/146433.

- ^ Jet Propulsion Laboratory (1962) (PDF). Mariner-Venus 1962 Final Project Report. SP-59. NASA.

- ^ Mitchell, Don (2003年). “Plumbing the Atmosphere of Venus”. The Soviet Exploration of Venus. 2007年12月27日閲覧。

- ^ "Report on the Activities of the COSPAR Working Group VII". Preliminary Report, COSPAR Twelfth Plenary Meeting and Tenth International Space Science Symposium. Prague, Czechoslovakia: National Academy of Sciences. 11–24 May 1969. p. 94.

- ^ Sagdeev, Roald (2008年5月28日). “United States-Soviet Space Cooperation during the Cold War”. 2009年7月19日閲覧。

- ^ Colin, L.; Hall, C. (1977). “The Pioneer Venus Program”. Space Science Reviews 20 (3): 283–306. Bibcode: 1977SSRv...20..283C. doi:10.1007/BF02186467.

- ^ Williams, David R. (2005年1月6日). “Pioneer Venus Project Information”. NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. 2009年7月19日閲覧。

- ^ Greeley, Ronald; Batson, Raymond M. (2007). Planetary Mapping. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-521-03373-2 2009年7月19日閲覧。

- ^ Hall, Loura (2016年4月1日). “Automaton Rover for Extreme Environments (AREE)” (英語). NASA 2017年8月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b David R. Williams (2014年5月29日). “Venus Exploration Timeline”. NASA. 2016年1月12日閲覧。

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (2012年8月28日). “An unheralded anniversary”. The Planetary Society. 2016年1月12日閲覧。

- ^ 引用エラー: 無効な

<ref>タグです。「cassini2nd」という名前の注釈に対するテキストが指定されていません - ^ “Venus Exploration Themes”. Venus Exploration Analysis Group. Lunar and Planetary Institute (2014年2月). 2016年1月12日閲覧。

- ^ Aaron J. Atsma. “Eospheros & Hespheros”. Theoi.com. 2016年1月15日閲覧。

- ^ Dava Sobel (2005). The Planets. Harper Publishing. pp. 53–70. ISBN 978-0-14-200116-5

- ^ Miller, Ron (2003). Venus. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7613-2359-4

- ^ Dick, Steven (2001). Life on Other Worlds: The 20th-Century Extraterrestrial Life Debate. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-79912-6

- ^ Seed, David (2005). A Companion to Science Fiction. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-1-4051-1218-5

- ^ a b c Stearn, William (May 1968). “The Origin of the Male and Female Symbols of Biology”. Taxon 11 (4): 109–113. doi:10.2307/1217734. JSTOR 1217734.

- ^ a b c Landis, Geoffrey A. (2003). "Colonization of Venus". AIP Conference Proceedings. Vol. 654. pp. 1193–1198. doi:10.1063/1.1541418。

引用エラー: <references> で定義されている name "meanplane" の <ref> タグは、先行するテキスト内で使用されていません。

<references> で定義されている name "iauwg_ccrsps2000" の <ref> タグは、先行するテキスト内で使用されていません。外部リンク[編集]

- Venus profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- Missions to Venus and Image catalog at the National Space Science Data Center

- Soviet Exploration of Venus and Image catalog at Mentallandscape.com

- Venus page at The Nine Planets

- Transits of Venus at NASA.gov

- Geody Venus, a search engine for surface features

金星表面地図作成のリソース[編集]

- Map-a-Planet: Venus by the U.S. Geological Survey

- Gazeteer of Planetary Nomenclature: Venus by the International Astronomical Union

- Venus crater database by the Lunar and Planetary Institute

- Map of Venus by Eötvös Loránd University